Social networks and the Third Sector: analysis of the use of Facebook and Instagram in 50 NGO in Spain and Chile

SOCIAL NETWORKS AND THE THIRD SECTOR: ANALYSIS OF THE USE OF FACEBOOK AND INSTAGRAM IN 50 NGO IN SPAIN AND CHILE

Redes sociales y tercer sector: análisis del uso de Facebook e Instagram en 50 ONG de España y Chile

Cecilia Claro Montes. Universidad de los Andes. Chile

Sonia Aránzazu Ferruz González. International University of La Rioja. Spain.

José Ignacio Catenacci Martín. Universidad Central. Chile.

How cite this article:

Claro-Montes, Cecilia, Aránzazu-Ferruz-González, Sonia, & Catenacci-Martín, José-Ignacio. (2024). Social networks and the Third Sector: analysis of the use of Facebook and Instagram in 50 NGO in Spain and Chile [Redes sociales y tercer sector: análisis del uso de Facebook e Instagram en 50 ONG de España y Chile]. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 82, 1-24. https://doi.org/10.4185/rlcs-2024-2197

ABSTRACT

Introduction: This study analyzes the use that the main NGO in Chile and Spain make of their profiles on Facebook and Instagram. Specifically, we study how they manage their public presence on these social networks, what issues they focus their activity on, how they are connecting with their audiences and the engagement they achieve. Methodology: the content analysis of the publications made by 50 NGO during a month has been used, taking into account quantitative and qualitative variables; the sample has been made up of 25 organizations from each country, selected by means of a non-probability sampling according to predefined criteria. Results: a total of 2,103 publications have been analyzed, which show that Facebook is the most used network, especially in Spain, and also the network with the largest number of followers; the use that NGO give to their profiles is basically informative, but there are differences between Spain and Chile and also by sector of activity of the organizations; the most used format for posting is text and notably the use of hashtags; the most common topics deal with the activities and projects of the NGO with a formal tone. Discussion: taking into account the social nature and the need to generate dialogue and connection with society, NGO should make more effort in their social media profiles given the scope and potential for generating engagement with their audiences. Conclusions: the communication strategies of the NGO in social networks do not take advantage of the power that these channels have to dialogue and establish relationships of trust with their audiences.

Keywords: NGO; Third Sector; social media; Instagram; Facebook; digital communication; social dialoguing.

RESUMEN

Introducción: El presente estudio analiza el uso que las principales ONG de Chile y España hacen de sus perfiles en Facebook e Instagram. En concreto se estudia cómo gestionan su presencia pública en estas redes sociales, en qué asuntos centran su actividad, cómo están conectando con sus públicos principales y cómo interactúa con ellos y el nivel de engagement que alcanzan. Metodología: se ha utilizado el análisis de contenido de las publicaciones realizadas por 50 ONG durante un mes, tomando en consideración variables cuantitativas y cualitativas; la muestra ha estado formada por 25 organizaciones de cada país, seleccionadas mediante un muestreo no probabilístico de acuerdo con criterios predefinidos. Resultados: se han analizado un total de 2.103 publicaciones, que muestran que Facebook es la red más utilizada, especialmente en España, y también la red con más número de seguidores; el uso que las ONG le dan a sus perfiles es fundamentalmente informativo, pero existen diferencias entre España y Chile y también por sector de actividad de las organizaciones; el formato más utilizado para postear es el texto y notable el uso de hashtags; los temas más habituales tratan las actividades y proyectos de las ONG con un tono formal. Discusión: tomando en consideración el carácter social y la necesidad de generar diálogo y conexión con la sociedad, las ONG deberían hacer más esfuerzo en sus perfiles de redes sociales dado el alcance y su potencialidad para la generación de interacción y engagement con sus públicos más relevantes. Conclusiones: las estrategias de comunicación de las ONG en redes sociales no aprovechan el poder que tienen estos canales para el diálogo y establecimiento de relaciones de confianza con sus públicos.

Palabras clave: ONG; Tercer Sector; redes sociales; Instagram; Facebook; comunicación digital; diálogo social.

1. INTRODUCTION

The Third Social Action Sector has substantial importance in the economies of Spain and Chile. In Spain, it represents approximately 1.41% of the national GDP and employs more than 500,000 people (Platform of Social Action NGOs, 2022). In Chile, it represents approximately 1.5% of the national GDP and employs more than 300,000 people (Soto and Viveros, 2016). In both countries, besides having a very similar weight, there has been a traditional presence of these organizations in addressing social needs and public welfare, especially since the 1980s during the establishment of democracy. In recent decades, it has been significantly affected by the economic crisis of 2008 and the recent COVID-19 crisis, with a widespread decline in both income and volunteers from which they are still recovering. This has forced social organizations to transform and professionalize themselves to address the new reality and the demands of their audiences.

As Macnamara (2016) indicates, the essence of a social organization, such as an NGO, is its collaborative capacity and the results it can generate by leveraging its networks and contact with stakeholders or interest groups. From the field of communication, it means working on processes by organizations to relate in the best possible way to their audiences or stakeholder groups, understood as those groups or individuals who can influence the achievement of an organization's objectives or be affected by it (Freeman, 1984). This means that "organizational communication must be understood as that which allows the members of an organization to send messages through different formal and informal media or channels to express their opinions and carry out their activities" (Rodríguez, 2019, p. 102).

This implies moving from one-way communication to a two-way one in which information is not only transmitted but also received to facilitate improvements. The one-way format, "when it occurs, is of poor quality and contributes very little to the goal of social transformation" (Iranzo and Farné, 2014, p. 21).

The above challenges institutions to listen to their audiences through continuous action (Claro, 2019) with the understanding that listening and speaking are requirements for achieving communication, dialogue, and bidirectionality in the relationship between parties (Macnamara, 2016, 2023).

Therefore, organizational listening is necessary since both individuals and institutions and organizations have access to a multitude of information generated by extensive sources that must be understood and contextualized (Lewis, 2020). Likewise, communication in institutions is expanding (Gutiérrez-García and Sadi, 2020), and the complexity and plurality of audiences require specific and dialogic communicative actions with different interest groups (Esparcia et al., 2020). Thus, social media (hereinafter referred to as RRSS) currently play a significant role in the communication of institutions and social organizations because they allow for direct dialogue with each relevant audience.

1.1. The communication of Third Sector organizations

When referring to non-governmental organizations (NGOs), various terminologies are used in the field of political science to describe this concept: civil society organizations, Third Sector, organized social movements, public interest groups, etc. (Muñoz-Márquez, 2014). The United Nations (UN) defines an NGO as a voluntary, non-profit organization of citizens at the national or international level (Vargas et al., 1992, p.3). Such an organization is a non-profit institution present in public life that expresses the values and interests of its members, adhering to ethical, cultural, political, scientific, religious, or philanthropic considerations (Neme et al., 2014). For Rodríguez-López (2005), third sector organizations - another term used for NGOs - are organizational forms that arise from society, characterized by their promotion of social cooperation and voluntary work, guided by altruistic and solidarity principles.

NGOs represent organized expressions of social and cultural trends and carry out various actions to solve problems, contributing to the structuring of social order and cooperating in different ways with the State and other actors (Delamaza and Mlynarz, 2021). Their actions and pursuit of citizen participation foster communication and listening processes that encourage greater participation, positioning, and problem-solving of social issues (Ceballos-Castro, 2020). With modernity and the advent of technology, the vital space-time relationship is disrupted (Monckeberg and Atarama, 2020). Building on this, Theunissen and Noordin (2012) predicted that public relations would increasingly focus on dialogues and conversations rather than one-way monologues, adapting to the free exchange of opinions among groups and collectives.

It's important to understand that these organizations have different characteristics. Some are more structured with organizational, financial, and infrastructural resources and interact with other institutions, unlike more spontaneous social movements, which lack organization and are self-managed (Delamaza and Mlynarz, 2021). These organizations generate social and relational capital, involving the integration of models of social interaction that contribute to the relationship forms among individuals, groups, and institutions, aiming to increase social welfare (Durán-Bravo, 2022). Organizational communication focuses on the meaning and construction of processes influenced by communication, the culture of institutions, and the creation of their identity (Palacios, 2015).

These entities should seek interaction and interpersonal group communication to increase their impact and presence. In this context, communication is seen as an "integral effort, collective and with a much broader and strategic vision" (Rebeil-Corella and Arévalo-Martínez, 2017, p. 26). In this interaction, organizational listening contributes to the generation of trust, commitment, and satisfaction with the goal of creating positive synergies (Palmatiere et al., 2006). Organizational listening has been associated with higher levels of participation in civil society (Reinikainen et al., 2020) and by both non-profit and for-profit organizations (Macnamara, 2016). Bidirectional communication between the organization and its audiences requires dialogue between the parties so that they can listen to each other. The two-way symmetrical model of communication (Grunig and Hunt, 2000) presupposes a dialogue that should lead the organization and the public to adapt their attitudes and behaviors based on the communication plan.

Authenticity is the vehicle that generates credibility and trust, establishing stable relationships with all stakeholder groups (Senent-García and Gandía Balaguer, 2021). If institutional communication is understood as an interaction process where actors exchange views and build mutual understanding together, it implies that communication involves dialogue and interaction among its participants to construct a joint agreement. Oliveira and Capriotti (2019) indicate that we are facing models in which the public is an active and interacting subject.

Focusing on the dialogical theory proposed by Taylor et al. (2003), organizations should be willing to interact honestly and ethically to create effective communication channels between the organization and its audiences (Kent and Taylor, 1998). These organizations require the support of their audiences to achieve their goals and manage their transparency (Rodríguez, 2021).

Social networks help cultivate relationships with target audiences (Wang and Yang, 2020), are a fundamental tool for brand positioning (Chu, 2011), and generate proactive interaction (Villena-Alarcón and Fernández-Torres, 2020). As indicated by Kent and Taylor (1998), this implies certain characteristics: reciprocity, the recognition of organization-public relationships; proximity, spontaneous interaction with the public; empathy or a sense of support; risk, the organization's willingness to communicate with its audiences on their own terms; and the organization's commitment to its public. Thus, communication should be understood as a social interaction built through discourse, gestures, texts, and other meanings. Specifically, Cornelissen et al. (2015) suggest that discourse and other symbolic forms of interaction are not only expressions of one's own thought or collective intentions but are potentially formative of institutional reality. In this regard, it is important to note that the use of social networks must be accompanied by a communication strategy in line with the values and principles of each organization. This aspect is especially relevant in the field of NGOs and the management of communication on social networks. The potential of these channels to generate reputational crises makes it particularly important for NGOs to carefully manage their communication through them, ensuring it reflects their mission and values (Ferruz-González, 2022).

1.2. Social Networks as Platforms for Communication and Interaction

Social networks are understood as "a group of Internet-based applications that are built on the ideological and technological foundations of Web 2.0 and enable the creation and exchange of user-generated content" (Kaplan and Haenlein, 2010, p. 61). These encompass various platforms that allow users to play an active role in the production, exchange, and updating of content on the social web, as well as interact with other users (Kaiser et al., 2020; Lovari and Valentini, 2020). Users can express themselves without the intervention of a third party (Fernández-Muñoz and Tomé-Caballero, 2020).

Social media is omnipresent in the lives of a massive group of people and is increasingly integrated into organizations (Bhimani et al., 2019). It differs from traditional media because individuals have access to a large amount of news that they must evaluate, and the access to information sources is faster (Sterrett et al., 2019). According to Gil-de-Zúñiga et al. (2022), the Internet and social networks facilitate relationships by minimizing the costs of interaction, and this interaction occurs in real-time. At the same time, this interaction generates participation, albeit unevenly, reduces social distances, and influences the nature of relationships in terms of how and when actions are taken (Pujalte, 2021; Fernández-Prados et al., 2021). The Internet has contributed to a more horizontal and interactive world (Shoai, 2018), where the "relational function" is "inherent in any social network" (Xifra and Grau, 2010, p. 173). Therefore, dialogic principles have been extensively used to evaluate the interactions of organizations with their audiences in these new relational environments facilitated by social networks.

Simultaneously, social networks allow individuals to acquire a large number of contacts with lower economic costs, reach a greater number of audiences, reduce organizational time, promote the construction of social identities, and create multiple channels of interpersonal conversation (Scherman et al., 2022; Vu et al., 2021). Social networks evolve, and new models emerge to interact with users. Social media encourages real-time user feedback, expands conversations, and strengthens ties between organizations and stakeholders (Lei et al., 2019). Unlike traditional media, non-governmental organizations can maintain constant contact with their audiences through social networks (Quiceno-Castañeda and Quirós-Ramírez, 2021).

Many non-profit organizations seek support, fundraising, community building, and the development of efficient and effective communication strategies based on the internet and social networks (Kim et al., 2014; Maqbool et al., 2019; Pujalte, 2020). They also promote initiatives and mitigate the effects of potential crises (Albanna et al., 2022; Lim et al., 2019) while involving their audiences in their activities (Durieux-Zucco et al., 2021). According to García-Galera et al. (2018), NGOs use social networks to become socially visible, generate knowledge and awareness about their activities, and use profiles as a channel for monetary support, a fundamental aspect for the survival of their projects. The various activities of these organizations create connections and form relationships with stakeholders, and the affected audiences can respond and interact differently with the organization's social networks. Therefore, social networks are an extremely useful tool for public relations strategy. It should be noted that public relations can be defined as "the communication processes between organizations (or individuals with public projection) and the audiences on which their activities depend, to establish and maintain relationships among all of them as mutually beneficial as possible" (Xifra, 2010, p. 11).

Social networks allow organizations to interact with audiences in a two-way dialogue that promotes knowledge generation and mutual commitment (Bellucci and Manetti, 2017; Campbell and Lambright, 2020), as well as enriching experiences (Capriotti et al., 2019). In this sense, the public relations strategy, responsible for ensuring relationships with audiences, should serve all stakeholders with whom the organization interacts, not just those of priority interest to the institution (Kent and Li 2020). They also facilitate working on specific topics and creating interest groups around them (Kent and Lane, 2021) and fostering discussions about them (Kent and Taylor, 2002).

The ability of social networks in the NGO sector to enable engagement, the commitment shown by users to the content they receive, is recognized by various authors (Campbell and Lambright, 2020; Carrasco et al., 2018; Cuenca et al., 2020). It is related to motivation, enthusiasm, and involvement with that content (Bergillos, 2017), which translates into the number of 'likes', comments, and times a piece of content has been shared. Therefore, measuring engagement takes into account the reach of the publication combined with the generated interaction (linked emojis, comments made, and number of times shared).

According to data from Statista (2023), Facebook (FB) leads in the number of users worldwide, with 2.96 billion users, while Instagram (IG) ranks fourth, following YouTube and WhatsApp, with 1.48 billion users. In the case of Chile, FB has 12.5 million users and is the most visited network, while IG has 11.5 million users and is the primary network in terms of usage time (Carrasco, 2022, Statista 2023). In Spain, social networks have 41 million users, with FB and WhatsApp being the most used (We are Social and Hootsuite, 2022); IG ranks fourth.

This study aims to understand how Third Sector organizations in Spain and Chile implement communication and engagement with their stakeholders on their social networks, specifically FB and IG, following the emergence of social networks as mass communication instruments.

2. OBJECTIVES

The purpose of the study is twofold. On one hand, it aims to understand how Third Sector organizations use social networks - specifically Facebook (FB) and Instagram (IG) - in terms of managing their public presence, focusing their activities on certain issues, and their interaction and relationship with different stakeholder groups. On the other hand, the study seeks to understand and compare the communication strategies of these organizations in different countries, specifically Spain and Chile, with the goal of discovering how they are connecting with their audiences, the differences (if any) in their approaches, and the type of interaction they engage in. This comparative analysis is enriching, as it allows us to discover not only how they adjust their communication strategies on these two social networks but also to identify if there are differences in usage between countries.

Related to the objectives, the following research questions are proposed:

- How and in what ways do Third Sector organizations use their profiles on IG and FB for communication purposes?

- Are there differences in the use and themes addressed on these networks in the studied countries? What are these differences?

- What is the nature of the interaction that these organizations have with their followers? Is there openness to dialogue, or do they focus on purely informational communication?

- Is it possible to establish differences in the use and interaction of the organizations with their followers based on the country?

3. METHODOLOGY

This study proposes to compare two Spanish-speaking realities, Spain and Chile, located on different continents. There is a notable number of NGOs present in both countries, which motivates this comparative study of communication realities.

To achieve the set objectives and answer the research questions, content analysis has been used, specifically its quantitative approach, which is suitable for carrying out a descriptive analysis of social media publications through quantitative and qualitative variables. This methodology has been widely used in the field of Social Sciences and has been employed in similar studies by various authors for analyzing the use of social networks by Third Sector Organizations (Durieux et al., 2021; Mut-Camacho and García-Huguet, 2023).

Specifically, the study analyzed the publications made by 25 active NGOs in Chile and another 25 active in Spain, over a month (from April 15 to May 15, 2022) on their Facebook (FB) and Instagram (IG) profiles. The choice of the month was not for a specific reason but corresponded to the timing of the study. It is noted that in both countries, May 1 is a holiday due to Labor Day.

These social networks were selected based on the criteria of usability and content variability: both are the most used social networks worldwide and allow a variety of content (We are Social and Hootsuite, 2022, p.99). WhatsApp was excluded due to the lack of profiles, contacts, and usage by NGOs; YouTube was excluded due to content limitations and because most of them do not have their own YouTube channels.

The sample selection was carried out through non-probabilistic or convenience sampling, considering the following criteria: an equal number of organizations from each country; covering different sectors of activity with the same representation in both countries; ideally, organizations active in both Spain and Chile; organizations with representativeness and recognition in their countries. The selected organizations should belong proportionally to different areas with universal and operational coverage according to the classification of the United Nations (United Nations, 2023), which distinguishes a wide range of issues often associated with the provision of services and social assistance to the most vulnerable groups (children, elderly), environmental issues (environment), and aid in emergency situations and public welfare (emergency, poverty-development, immigration-refugees). Of the total sample (50 organizations), 20% have a presence in both nations.

Table 1. Organizations that Make Up the Sample.

|

SPANISH ORGANIZATIONS |

TYPE |

CHILE ORGANIZATIONS |

TYPE |

|

Unicef España |

Childhood. |

Unicef Chile |

Childhood. |

|

Aldeas Infantiles España |

Childhood. |

Aldeas Infantiles Chile |

Childhood |

|

Save the Children |

Childhood. |

Sociedad Protectora de la Infancia |

Childhood. |

|

World Vision España |

Childhood. |

World Vision Chile |

Childhood. |

|

Fundación Más Vida |

Childhood. |

Make a Wish |

Childhood. |

|

Fundación Edad y Vida |

Elders |

Fundación mi casa |

Childhood. |

|

Amigos de los Mayores |

Eldes |

Corporación CreArte |

Childhood. |

|

Cruz Roja España |

Emergency |

Cruz Roja Chile |

Emergency |

|

Médicos sin Fronteras |

Emergency

|

Hogar de Cristo |

Elders |

|

Plan Internacional |

Emergency

|

Fundación las Rosas |

Emergency |

|

Médicos del Mundo España |

Emergency

|

Fundación Fútbol Más |

Childhood |

|

Acción Contra el Hambre |

Emergency

|

Desafío Levantemos Chile |

Emergency |

|

Greenpeace España |

Environment |

Greenpeace Chile |

Environment |

|

Amigos de la Tierra España |

Environment |

Techo |

Emergencia |

|

WWF España |

Environment |

WWF Chile |

Environment |

|

Seo Birdlife |

Environment |

Terram |

Environment |

|

Oceana Europa |

Environment |

Oceana Chile |

Environment |

|

Acnur España |

Migration-Refugees |

Acnur Chile |

Migration-Refugees |

|

Amnistía Internacional España |

Migration-Refugees |

Amnistía Internacional Chile |

Migration-Refugees |

|

ACCEM |

Migration-Refugees |

Servicio Jesuita a migrantes |

Migration-Refugees |

|

CESAL |

Migration-Refugees |

Fundación de Ayuda Social de las Iglesia cristianas |

Migration-Refugees |

|

CEAR |

Migration-Refugees |

Fundación Red Inmigrante |

Migration-Refugees |

|

Oxfam Intermon |

Poverty-Development Cooperation. |

Fundación Superación de la Pobreza |

Poverty-Development Cooperation. |

|

Mensajeros de la Paz |

Poverty-Development Cooperation. |

Fundación América Solidaria |

Poverty-Development Cooperation. |

|

Manos Unidas España |

Poverty-Development Cooperation. |

Manos Unidas Chile |

Poverty-Development Cooperation. |

Source: Author's own work.

The study analyzed the publications made by the organizations and the respective interactions generated from them with their followers. The variables considered in the analysis were organized into blocks; the first block focused on understanding the presence of NGOs on social networks; and a second block with variables centered on collecting information about the use NGOs make of these social networks.

Table 2. Definition of Analyzed Variables.

|

Variable |

Description |

Type of Classification. |

|

Spain or Chile |

Excluding |

|

National or International |

Excluding |

|

Childhood Elderly Emergency Immigration-Refugees Poverty - Development Cooperation |

Excluding |

|

Post Date |

Does not apply |

|

Daily Posts per Organization |

Does not apply |

|

Number of Followers per Institution on FB and IG |

Does not apply |

|

Whether the Publication Originates from the Organization or Collaborators |

Excluding |

|

Text / Image / Audio / Video / Hashtag |

Complementary |

|

Total Interactions of the Publication |

Does not apply |

|

Funding General Activity Projects Volunteers Others |

Complementary |

|

General or Sectoral |

Excluding |

|

Informational/Dissemination Relational/Interaction |

Excluyente |

|

Work Citizenship Integrity |

Excluyente |

|

Emoji: Like / Love / Care Haha / Wow / Sad Angry |

Complementary |

|

Comment Shared |

Excluding |

|

Positive Negative Neutral |

Excluding |

|

Formal Informal

|

Excluding |

Source: Author's own work.

The selection of these variables responds to various criteria. Regarding the format and language used in the publications, the perspective of Osorio et al., (2020) has been considered, indicating that emojis are relevant for driving user interaction with posts, with various types of interactions and types of comments. This aspect provides insights into the degree of user commitment to an organization or engagement, and allows correlating the level of public involvement with the content shared by NGOs.

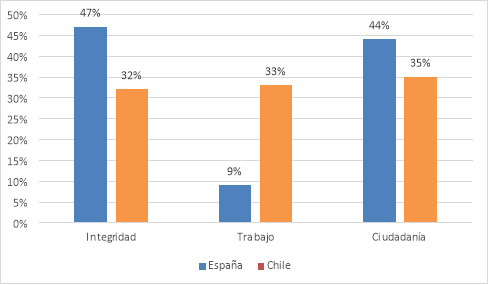

In terms of communicative objectives, they have been identified according to the contributions of Peruzzo (2013), who proposes two types of communications made by NGOs: institutional communication, about general matters of the organization with an informational and awareness-raising focus; and mobilizing communication, aimed at involving beneficiaries and volunteers, with a clear relational or interaction focus. Finally, given the social nature of these organizations, the relevance of social responsibility activities for NGOs has been analyzed according to the classification by Capriotti and Zeler (2020), which refers to three categories: ‘integrity’ or information related to commitments, strategies, policies, and responsible practices; ‘work’ or information on labor and employment aspects of the organization and information on commitments, strategies, policies, and responsible practices in the management of the organization's human resources; and ‘citizenship’ or information related to the commitments, strategies, policies, and responsible practices of the company at the social and environmental level.

The coding was done independently by three coders who initially worked with the researchers to agree on criteria and the meaning of categories. They carried out a pilot work which was reviewed together by the researchers to ensure homogenization in the analysis and reduce subjectivity. After this check, the rest of the analysis was carried out according to the selection and recording criteria proposed by the researchers. During the analysis, four meetings were held to check the data processing and clarify doubts, especially those arising from the posts and the feedback generated from each. This resolved some doubts that could arise from points 16 and 17 of Table 2. After the delivery of that report, the authors of this article reviewed the data and then processed it for the purposes of this study.

4. RESULTS

A total of 2,399 posts on FB and IG were collected, 1,101 from Spanish organizations and 1,298 from Chilean organizations. After an initial review of the publications according to the established criteria, the sample was adjusted, and posts that could not be recovered for analysis were excluded. This exclusion was either because the organizations deleted them after editing (duplicates) or because they were removed after a few hours. The final sample consisted of a total of 2,103 publications, 1,099 from Spain and 1,004 from Chile.

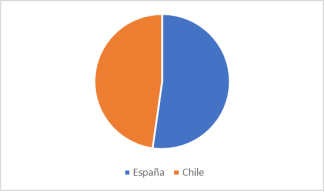

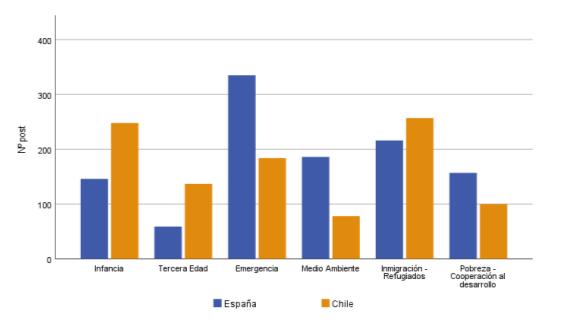

Figure 1: Significance of the Publications of the Organizations Spain-Chile.

Source: Author's own work.

Before going into detail, it's necessary to contextualize the presence of NGOs on social networks in terms of their activity. In this context, 36% of NGOs in Spain post less than one post per day on their social networks; similarly, in Chile, 40% of organizations do not reach an average of one post per day. The rest of the organizations in both countries post at least two posts daily, with the Red Cross in both countries leading by posting an average of 4.8 posts per day in Chile and 5.8 posts in Spain.

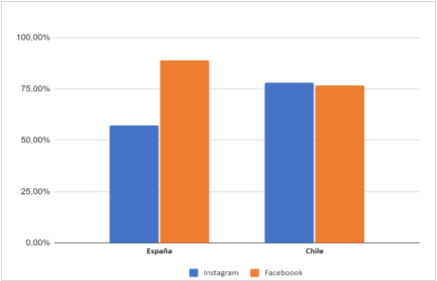

Regarding the social networks used, it is evident that in Spain, FB is the most used with 61% versus 39% for IG. In Chile, the situation is different, as there is a similar usage of both networks under analysis. In Figure 2, these data are represented, and it is also observed that FB is the most used social network globally by NGOs. It 's also important to note that all 50 organizations have a profile on FB, but there are 3 that do not have one on IG, one in Spain - Fundación Edad y Vida - and two in Chile - Fundación Mi Casa and Fundación Fútbol Más.

Figure 2: Percentage of publications by social network in Spain and Chile.

Source: Author's own work.

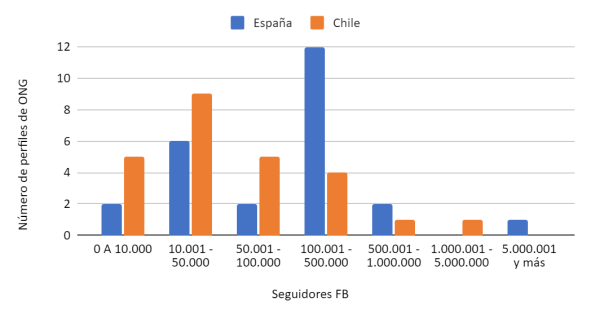

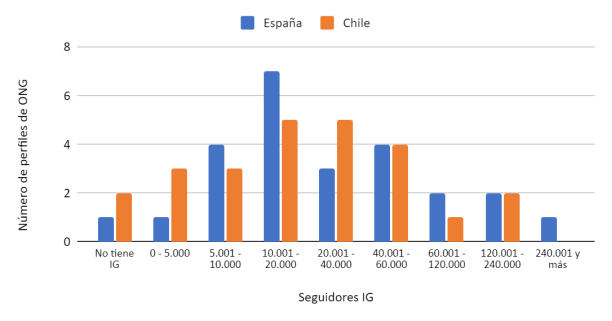

It is also worth mentioning the data regarding the followers of organization profiles. Facebook is the platform where NGOs in both countries obtain the largest number of followers (Figure 3), although there are more Spanish organizations with figures above 100,000 followers. Regarding Instagram (Figure 4), the number of followers in general is much lower, and the highest range - more than 240,000 followers - is much lower than the figures we find for followers on Facebook; in fact, we see that there are 3 organizations that do not have profiles on Instagram - 2 Chilean and 1 Spanish.

Figure 3: NGO profiles on Facebook by number of followers and by country.

Source: Author's own work

Figure 4: NGO profiles on Facebook by number of followers and by countries.

Source: Author's own work

Regarding the results disaggregated by countries and qualitative variables, differences are also observed. First of all, the results show that the weight of the publications by organizations in different sectors varies in each country, with the activity of organizations in the Emergency sector being prominent in Spain and that of the Immigration-Refugees sector in Chile (Figure 5). The difference is particularly notable in sectors such as Childhood, Elderly, and Environment, where the variations can even double the activity from one country to another.

Figure 5: Publications by sectors on Facebook and Instagram in Spain and Chile.

Source: Author's own work.

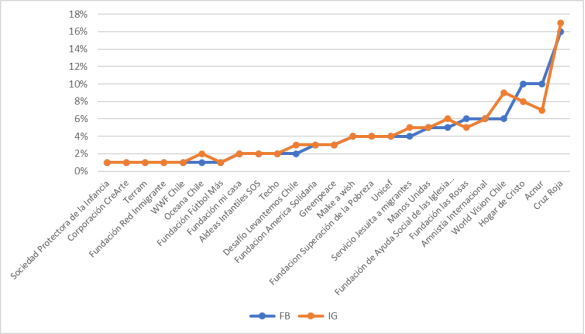

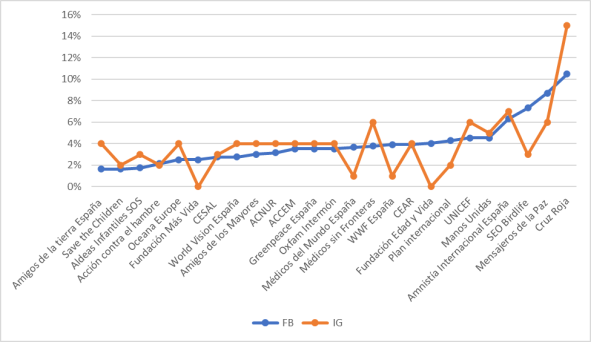

Regarding the organizations that use social media the most, the following figures indicate the percentage of posts from the total period according to the two studied networks by country (Figures 6 and 7). In both countries, Cruz Roja (Red Cross) leads in the number of posts on both social networks, and Amnistía Internacional (Amnesty International) also stands out among the top five. The rest of the organizations that use social media the most differ in each country, despite some of them being international organizations with a presence in both countries, such as Aldeas Infantiles (SOS Children's Villages) or WWF. As for the balance of posts between networks by each organization, there is more homogeneity in Chile than in Spain, where there are organizations with significant differences in the number of posts on each social network, such as Médicos del Mundo (Doctors of the World), WWF, Fundación Edad y Vida (Age and Life Foundation), and Cruz Roja itself.

Figure 6: Percentage of posts on each social network by Chilean NGOs.

Source: Author's own work.

Figure 7. Percentage of posts on each social network by Spanish NGOs.

Source: Author's own work.

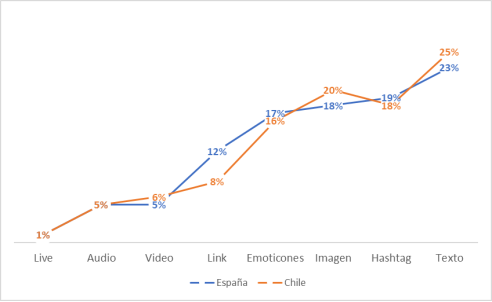

Regarding the communication methods used by organizations, it is observed that in the studied social networks, text is the most common format on average. The use of hashtags is also relevant, while the use of videos is limited. However, it is evident that NGOs use a variety of formats, and the usage is very similar in both countries.

Figure 8: Publication formats on Facebook and Instagram by country.

Source: Author's own work.

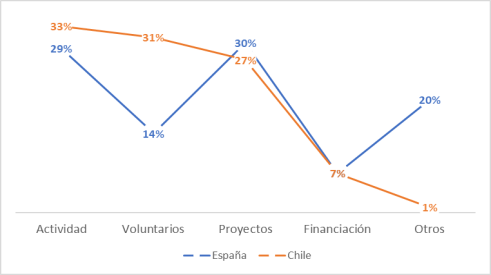

Regarding the types of topics that organizations post about in the analyzed period, among Spanish NGOs, the most frequently published topics are related to 'projects' (30%), 'activity' (29%), and 'other' with 20%. In the case of Chile, the most published topics are also related to activities carried out (33%) and projects (27%), but there is a notable difference in the publication of information about 'volunteers' (31%) compared to Spain (14%).

Figure 9: Topics of publications on Facebook and Instagram by countries.

Source: Author's own work.

The above information is complemented by indicating that in Spain, 70% of the posts are sector-specific, and only 30% are general, while in the case of Chile, it's 64% sector-specific and 36% general.

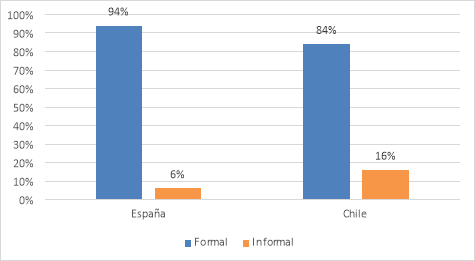

Regarding the style of the publications, there is a clear majority of 'formal' posts where information is presented in non-transgressive formats with limited use of typically persuasive resources, and with appropriate writing and spelling. In contrast, 'informal' posts have a colloquial writing style, multiple punctuation marks, and an emphasis on correct language usage (Martínez-Lirola, 2012). It is possible to observe slight differences between countries, with Chilean NGOs having a higher proportion of informal publications.

Figure 10.Style of publications on Facebook and Instagram by NGOs in Spain and Chile.

Source: Author's own work.

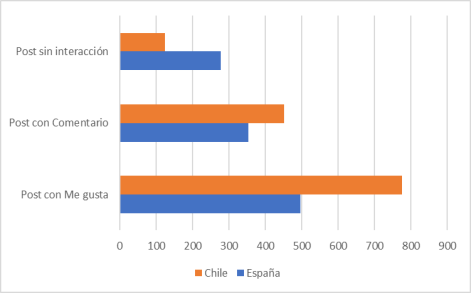

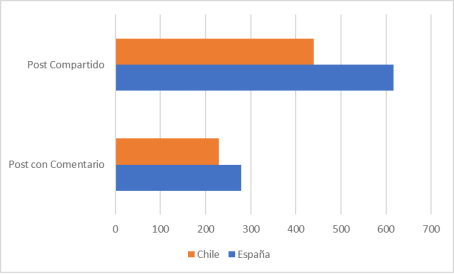

Regarding engagement with the posts posted in both Spain and Chile on the two studied social networks, it can be noted that in the case of Chile, there are more interactions and comments on the posts of organizations compared to Spain, both on Instagram and Facebook.

As indicated by Cuenca et al. (2020), the Instagram metric 'Likes' has an impact on followers as it gives them a perception of the positivity of the post, while 'Comments' demonstrate user interaction and encourage others to share and express their opinions.

Figure 11. Type of interaction on Instagram by countries.

Source: Author's own work.

It is important to highlight that when a user shares information on Facebook, they may not necessarily verify the authenticity of the content or check its source, but they can become a sort of influencer for their followers (Espinoza-Oliva, 2021).

Figure 12. Type of interaction on Facebook by countries.

Source: Author's own work.

Finally, concerning the social responsibility activities of organizations and their reflection in social media posts, we observe that 'integrity' and 'citizenship' are more prominent in Spain compared to Chile, while 'work' is clearly more emphasized in Chile.

Figure 13. Topics related to Social Responsibility.

Source: Author's own work.

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

We observe that there are no significant differences between NGOs in Chile and Spain in terms of using social media as communication channels, as the number of posts they publish in the same period is quite similar. However, differences are noted in the most-used social network - Facebook in Spain and Instagram in Chile - as well as in the number of followers. Clearly, Facebook profiles have more followers in both countries, with a significant difference compared to Instagram profiles, which often don't even reach half the number of followers of their Facebook counterparts. Considering that Facebook has a higher age range, this could be the main reason for the significant difference in the number of followers. Nevertheless, it's important to consider the interaction data for each network, and according to the Digital 2022 global overview report by Hootsuite and We Are Social (Hootsuite, 2022), Instagram users are the ones who publish and share the most content. Therefore, NGOs should put more effort into their Instagram profiles as channels with greater potential for generating engagement and reach.

Differences are also observed in how NGOs in different sectors use social media. Organizations in the Immigration and Refugee and Emergency sectors are the most active on social media in both countries. However, there are differences in the volume of activity between Spanish and Chilean Emergency organizations, with Spanish organizations almost doubling their activity compared to their Chilean counterparts. There are also disparities between countries in the Childhood and Environment sectors, with Childhood being a prominent area of action in Chile compared to Spain, and vice versa for the Environment sector. Finally, it's worth noting the limited use of social media by organizations in the Elderly sector in Spain compared to Chile, where they are much more active. These results give us an idea of the most common issues in each country and how NGOs address them. Further research could compare public investments in these areas with campaigns conducted by NGOs.

In summary, a significant portion of NGOs make limited use of social media channels in their communication strategy, as they don't even publish one post per day (36% and 40%, respectively, in Spain and Chile). This suggests that social media are not heavily used in their communication strategy and are not part of a planned usage. This aspect has been mentioned in previous research on NGOs' social media (Mut-Camacho and García-Huguet, 2023) and underscores that these organizations still have room for improvement in using social media for strategic communication. Social media are suitable channels for generating awareness and engagement with key audiences, especially on Instagram, as mentioned earlier.

Regarding the most used formats (Figure 8), we see that text and hashtags are the most common formats, with no significant differences between countries. This data suggests that the use of hashtags has become normalized in all types of posts, even those using images or videos. It's also noteworthy that video usage in posts is relatively low, considering its importance in recent years as a format of interest to audiences, especially on Instagram.

As for the objectives pursued by NGOs in their content strategy on social media, it appears that the studied organizations are not necessarily using social media to increase their visibility, gain recognition, or seek financial assistance. The primary focus of this study is communication related to projects and activities, with fundraising ranking third in their campaigns. It also doesn't seem clear that there is a greater dialogue with users; instead, the communication tends to be one-way, and the content rarely addresses volunteer topics, which could open the door to greater interaction with these key audiences of NGOs. These findings are in line with previous research and highlight that NGOs have only begun to use social media for strategic communication and are not fully utilizing the interaction options that social media offer, as mentioned by Iranzo and Farné (2014).

Since the average Instagram user spends half as much time on Instagram as the average TikTok user spends on TikTok, it would be interesting in the future to analyze NGO profiles on TikTok to understand their activity and how these organizations are positioning themselves among younger users, who are the majority on this social network.

In conclusion, this study has shown that there are differences in the use of social media both between countries and among sectors and social networks, as discussed in previous paragraphs. This is undoubtedly one of the main contributions of this study. It has also highlighted that the communication usage by Third Sector organizations on Instagram and Facebook is primarily informative and not very interactive. This leads us to conclude that there is limited listening by organizations to the audiences they address through Facebook and Instagram. This is despite the fact that they often have a significant number of followers with whom they do not intend to interact or engage in communicative dialogue, but rather to keep them informed about their main activities and projects. Therefore, we believe there is much room for improvement in building trust between NGOs and their audiences.

One of the main limitations of this study is the limited access to a larger database that would allow for a more universal inclusion of all types of civil society organizations, rather than being limited to specific sectors due to limited resources, as is the case in this study. For future research, it would be interesting to study the usage of these social networks in other Latin American countries, as well as to compare usage in English-speaking versus Spanish-speaking countries, where differences in usage could be found. It would also be valuable to include networks with different characteristics, such as X and TikTok, which would provide additional elements for communication analysis.

6. REFERENCES

![]() Albanna, H., Alalwan, A. A. y Al-Emran, M. (2022). An integrated model for using social media applications in non-profit organizations. International journal of information management, 63, 102452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102452

Albanna, H., Alalwan, A. A. y Al-Emran, M. (2022). An integrated model for using social media applications in non-profit organizations. International journal of information management, 63, 102452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102452

Bellucci, M. y Manetti, G. (2017). Facebook as a tool for supporting dialogic accounting? Evidence from large philanthropic foundations in the United States. Accounting, Auditing y Accountability Journal. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-07-2015-2122

Bergillos, I., (2017). ¿Dos caras de la misma moneda?: una reflexión sobre la relación entre engagement y participación en medios. Comunicación y Hombre, 14, 119-134.

Bhimani, H., Mention, A. L. y Barlatier, P. J. (2019). Social media and innovation: A systematic literature review and future research directions. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 144, 251-269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.10.007

Campbell, D. A. y Lambright, K. T. (2020). Terms of engagement: Facebook and Twitter use among nonprofit human service organizations. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 30(4), 545-568. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21403

Capriotti, P. y Zeler, I. (2020). Comunicación de la responsabilidad social empresarial de las empresas de América Latina en Facebook: estudio comparativo con las empresas globales. Palabra Clave, 23(2), e2327. https://doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2020.23.2.7

Capriotti, P., Zeler, I. y dos Santos, A. O. (2019). Comunicación dialógica 2.0 en Facebook. Análisis de la interacción en las organizaciones de América Latina. Revista latina de comunicación social, 74, 1094-1113. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2019-1373

Carrasco, D. (2022). Redes sociales en Chile: perfiles y número de usuarios. Marketing4ecommerce. https://marketing4ecommerce.cl/redes-sociales-en-chile-numero-usuarios/

Carrasco, R., Villar, E. y Martín, M. (2018). Artivismo y ONG: Relación entre imagen y «engagement» en Instagram. Comunicar, XXVI(57), 29-38. https://doi.org/10.3916/C57-2018-03

Ceballos-Castro, G. (2020). Tercer Sector español ante la comunicación, el desarrollo y el cambio social. Convergencia, 27. https://doi.org/10.29101/crcs.v27i0.12073

Chu, S. C. (2011). Viral Advertising in Social Media: Participation in Facebook Groups and Responses among College-Aged Users. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 12(1), 30-43.

Claro, C. (2019). La escucha organizacional: una propuesta conceptual. Anagramas-Rumbos y sentidos de la comunicación-, 17(34), 239-253. https://doi.org/10.22395/angr.v17n34a12

Cornelissen, J. P., Durand, R., Fiss, P. C., Lammers, J. C. y Vaara, E. (2015). Putting communication front and center in institutional theory and analysis. Academy of Management Review, 40(1), 10-27. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2014.0381

Cuenca, S. M., Espinoza, J. E. y Bonisoli, L. (2020). Engagement en Instagram, ¿un asunto de género? Revista Espacios, 41(17). https://www.revistaespacios.com/a20v41n17/a20v41n17p18.pdf

Delamaza, G. y Mlynarz, D. (2021). Ensayo crítico sobre el marco político-institucional de la sociedad civil en Chile: aciertos, limitaciones y desafíos. Centro de Políticas Públicas UC Sociedad en Acción. https://bit.ly/44z95nY

Durán-Bravo, P. (2022). Dirección estratégica de la comunicación en las OTS. En L. López-Font (Ed.), Comunicación y Tercer Sector de Acción Social. Miscelánea sobre la reputación de las ONG en España y Latinoamérica (pp. 111-141). Tirant humanidades.

Durieux-Zucco, F., Machado, J., Boos de Quadros, C. M. y Foletto Fiuza, T. (2021). Comunicación en el tercer sector antes y durante la Pandemia COVID-19: estrategias de comunicación en las redes sociales de las ONG de Blumeneau, Santa Catarina, Brasil. En Ámbitos, 52, 140-155. https://dx.doi.org/10.12795/Ambitos.2021.i52.09

Esparcia, A. C., Moreno, Á. y Capriotti, P. (2020). Relaciones públicas y comunicación institucional ante la crisis del COVID-19. Revista Internacional de Relaciones Públicas, 10(19), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.5783/RIRP-19-2020-01-01-06

Espinoza-Oliva, A. (2021). Likes o votos. Análisis de una campaña Política en Facebook. Revista Ciencia Administrativa, 2. https://www.uv.mx/iiesca/files/2022/04/06CA2021-2.pdf

Fernández-Muñoz, C. y Tomé-Caballero, M. (2020). Empleo del storytelling y las narrativas en primera persona en la comunicación de Las Kellys como referente para las ONGs. Profesional de la información, 29(3), e290325. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.may.25

Fernández-Prados, J. S., Carmona, C. A., Palomo, M. T. M. y Muyor-Rodríguez, J. (2021). El activismo digital desde la mirada de las ONG y las personas jóvenes. New Trends in Qualitative Research, 9, 96-101.https://doi.org/10.36367/ntqr.9.2021.96-101

Ferruz-González, S. A. (2022). Gestión de la reputación y riesgo reputacional en el TSAS. En L. López-Font, (Ed.), Comunicación y Tercer Sector de Acción Social. Miscelánea sobre la reputación de las ONG en España y Latinoamérica (295-319). Tirant humanidades.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Pitman Publishing Inc.

García-Galera, C., Muñoz, C. F. y del Olmo Barbero, J. (2018). La comunicación del Tercer Sector y el compromiso de los jóvenes en la era digital. ZER: Revista de Estudios de Comunicación, Komunikazio Ikasketen Aldizkaria, 23(44). https://doi.org/10.1387/zer.19164

Gil-de-Zúñiga, H., Mateos A. e Inguanzo, I. (2022). Repensando el capital social en la era digital y en sociedades diversas. Revista Internacional de Sociología, 80(4), e214. https://doi.org/10.3989/ris.2022.80.4.MI22-0001

Gutiérrez-García, E. y Sadi, G. (2020). Capacidades profesionales para el mañana de la comunicación estratégica: contribuciones desde España y Argentina. Revista de Comunicación, 19(1), 125-148. https://doi.org/10.26441/RC19.1-2020-A8

Grunig, J. E. y Hunt, T., (2000). Dirección de relaciones públicas. Gestión 2000.

Iranzo, A. y Farné, A. (2014). Herramientas de comunicación para el tercer sector: el uso de las redes sociales por las ONGD catalanas. Commons: revista de comunicación y ciudadanía digital, 3(2), 28-55. https://doi.org/10.25267/COMMONS.2014.v3.i2.03

Kaplan, A. M. y Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Business horizons, 53(1), 59-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003

Kaiser, C., Ahuvia, A., Rauschnabel, P. A. y Wimble, M. (2020). Social media monitoring: ¿What can marketers learn from Facebook brand photos? Journal of business research, 117, 707-717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.09.017

Kent, M. L. y Lane, A. (2021). Two-way communication, symmetry, negative spaces, and dialogue. Public Relations Review, 47(2), 102014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2021.102014

Kent, M. L. y Taylor, M. (2021). Fostering dialogic engagement: Toward an architecture of social media for social change. Social Media + Society, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120984462

Kent, M. L. y Li, C. (2020). Toward a normative social media theory for public relations. Public Relations Review, 46(1), 101857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2019.101857

Kent, M. L. y Taylor, M. (2002). Toward a dialogic theory of public relations. Public relations review, 28(1), 21-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0363-8111(02)00108-X

Kent, M. L. y Taylor, M. (1998). Building dialogic relationships through the world wide web. Public Relations Review, 24(3), 321-334. https://doi.org.10.1016/S0363-8111(99)80143-X

Kim, D., Chun, H., Kwak, Y. y Nam, Y. (2014). The employment of dialogic principles in website, Facebook, and Twitter platforms of environmental nonprofit organizations. Social science computer review, 32(5), 590-605. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439314525

Lei, L., Li, Y. y Luo, Y. (2019). Production and dissemination of corporate information in social media: A review. Journal of Accounting Literature, 42(1), 29-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acclit.2019.02.002

Lewis, L. (2020). The power of strategic listening. Rowman y Littlefield.

Lim, W. M., Lim, A. L. y Phang, C. S. C. (2019). Toward a conceptual framework for social media adoption by non-urban communities for non-profit activities: Insights from an integration of grand theories of technology acceptance. Australasian Journal of Information Systems, 23. https://doi.org/10.3127/ajis.v23i0.1835

Lovari, A. y Valentini, C. (2020). Public sector communication and social media: Opportunities and limits of current policies, activities, and practices. The handbook of public sector communication, 315-328. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119263203.ch21

Macnamara, J. (2023). Digital corporate communication and organizational listening. En V. Luoma-Aho, & M. Badham (ed.), Handbook on Digital Corporate Communication, (pp. 357-370). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Macnamara, J. (2019). Explicating Listening in Organization–Public Communication: Theory, Practices, Technologies. International Journal of Communication, 13(22). https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/11996

Macnamara, J. (2016). Organizational listening: Addressing a major gap in public relations theory and practice. Journal of Public Relations Research, 28(3-4), 146-169. https://doi.org/10.1080/1062726x.2016.1228064

Martínez-Lirola, M. D. (2012). Aproximación a la interacción virtual: el caso de la red social Badoo. Palabra Clave, 15(1), 107-127.

Maqbool, N., Razzaq, S., Ul Hameed, W., Atif Nawaz, M. y Ali Niaz, S. (2019). Advance fundraising techniques: an evidence from non-profit organizations. Pakistan journal of humanities and social sciences, 7(1), 147-157. https://doi.org/10.52131/pjhss.2019.0701.0077

Mönckeberg, M., y Atarama Rojas, T. (2020). Comunicación líquida en el pensamiento de Zygmunt Bauman: el espacio y el tiempo para la construcción de sentido. ComHumanitas: revista científica de comunicación, 11(1), 131-148. https://doi.org/10.31207/rch.v11i1.233

Muñoz-Márquez, L. (2014). A vueltas con las ONG: perspectivas teóricas sobre su papel en el proceso político. Revista Mexicana de Análisis Político y Administración Pública, 3(2), 275-296. https://bit.ly/35KtN7q

Mut-Camacho, M. y García-Huguet, L. (2023). Presencia y objetivos perseguidos del uso de las redes sociales por parte de ONGD españolas de mujeres. En L. López-Font (Ed.), Comunicación y Tercer Sector de Acción Social. Miscelánea sobre la reputación de las ONG en España y Latinoamérica (pp. 269-293). Tirant Humanidades.

Neme O., Valderrama A. y Vázquez Á. M. (2014). Organizaciones de la sociedad civil y objetivos de desarrollo del milenio: el caso del PCS. Espiral, 21(60), 131-177.

Oliveira, A. y Capriotti, P. (2019). El propósito de las relaciones públicas: de la persuasión a la influencia mutua. Comunicació: revista de recerca i d'anàlisi, 2(36), 53-70. https://.doi.org/10.2436/20.3008.01.184

Osorio A., Carlos F., Peláez Muñoz, J. y Rodríguez Orejuela, A. (2020). Cantidad adecuada de emojis y caracteres para generar eWOM en Facebook. Suma de Negocios, 11(24), 24-33. http://doi.org/10.14349/sumneg/2020.V11.N24.A3

Palmatiere, R., Rajiv P. D., Dhruv G. y Kenneth E. (2006). Factors Influencing the Effectiveness of Relationship Marketing: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Marketing, 70, 136-153. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.70.4.1

Palacios, J. (2015). Historia y avances en la investigación en comunicación organizacional. Revista internacional de relaciones públicas, 5(10), 25-46. https://doi.org/10.5783/revrrpp.v5i10.339

Peruzzo, C. (2013). Movimentos sociais, redes virtuais e mídia alternativa no junho em que “o gigante acordou”. MATRIZes, 7(2), 73-93. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.1982-8160.v7i2p73-93

Plataforma de ONG de Acción social. (2022). El Tercer Sector de Acción Social en España 2021: Respuesta y resiliencia durante la pandemia. https://bit.ly/3reZswT

Pujalte, L. Q. (2021). Relaciones públicas y tecnología: la interactividad como punto de encuentro entre las ONG y sus públicos. Revista Internacional de Relaciones Públicas, 11(21), 49-68. https://doi.org/10.5783/revrrpp.v11i21.696

Pujalte, L. Q. (2020). Comunicación digital y ONG: disputa entre la cultura organizacional, el discurso transformador y el fundraising. Prisma Social: revista de investigación social, 29, 58-79.

Quiceno-Castañeda B. E. y Quirós-Ramírez, A. C. (2021). Redes sociales y relaciones públicas en las ONG: recaudación de fondos en línea como estrategia de financiación en tiempos de paz. En J. Sierra-Sánchez y A. Barrientos-Baez (Eds.), Cosmovisión de la comunicación en redes sociales en la era postdigital (pp. 577-594). McGraw Hill.

Rebeil-Corella, M. A. y Arévalo-Martínez, R. (2017). Las organizaciones y sus procesos de comunicación: una visión integral. En R. Arévalo-Martínez y G. Guillén-Ojeda (Eds.). La comunicación para las organizaciones en México (25-40). Tirant humanidades.

Reinikainen, H., Kari, J. T. y Luoma-Aho, V. (2020). Generation Z and organizational listening on social media. Media and Communication, 8(2), 185-196. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v8i2.2772

Rodríguez, H. O. (2021). Comunicación Integral y transparencia en las organizaciones del tercer sector/Integral Communication and transparency of the third sector organizations. Revista Internacional de Relaciones Públicas, 11(21), 05-26. https://doi.org/10.5783/revrrpp.v11i21.692

Rodríguez, H. O. (2019). La comunicación integral en las organizaciones del tercer sector. Sintaxis, 2, 95-112. https://doi.org/10.36105/stx.2019n2.06

Rodríguez-López, J. (2005). Tercer sector: una aproximación al debate sobre el término. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 11(3), 464-474.

Senent-García, J. y Gandía Balaguer, R. (2022). Prólogo. En L. López-Font (Ed.), Comunicación y tercer sector de acción social. Miscelánea sobre la reputación de las ONG en España y Latinoamérica. Tirant humanidades.

Shoai, A. (2018). Participación, relevancia y discernimiento: tres ejes para evaluar normativamente el desarrollo y uso de las redes sociales en la consultoría de comunicación. En H. Aznar, M. Pérez-Gabaldón, E. Alonso, A. Edo (eds.), El derecho de acceso a los medios de comunicación. II. Participación ciudadana y de la sociedad civil (pp. 141-162). Tirant lo Blanch.

Soto Barrientos, F. y Viveros Caviedes, F. (2016). Organizaciones de la sociedad civil en Chile: propuestas para financiamiento público y fortalecimiento institucional. Polis, 15(45), 429-454. https://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-65682016000300021

Sterrett, D., Malato, D., Benz, J., Kantor, L., Tompson, T., Rosenstiel, T. y Loker, K. (2019). Who shared it? Deciding what news to trust on social media. Digital journalism, 7(6), 783-801. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1623702

Scherman, A., Valenzuela, S. y Rivera, S. (2022). Youth environmental activism in the age of social media: the case of Chile (2009-2019). Journal of Youth Studies, 25(6), 751-770. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2021.2010691

Statista. (2023). Ranking mundial de redes sociales por número de usuarios. https://bit.ly/3D2Jzfk

Taylor M., Kent M. y White, W. J. (2001). How activist organizations are using the Internet to build relationships. Public Relations Review, 27, 263-284, https//doi.org/10.1016/S0363-8111(01)00086-8

Theunissen, P. y Noordin, W. N. W. (2012). Revisiting the concept “dialogue” in public relations. Public Relations Review, 38(1), 5-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2011.09.006

United Nations. (2023). About Civil Society. https://www.un.org/en/civil-society/page/about-us

Vargas C. H., Arango, J. B. T. y Rodríguez M. (1992). Acerca de la naturaleza y evolución de los Organismos no Gubernamentales (ONGs) en Colombia. Fundación Social.

Villena-Alarcón, E. y Fernández-Torres, M. J. (2020). Relaciones con los públicos a través de Instagram: los influencers de belleza como caso de estudio. Revista Internacional de Relaciones Públicas, 10(19), 111-132. http://dx.doi.org/10.5783/RIRP-19-2020-07-111-132

Vu, H. T., Blomberg, M., Seo, H., Liu, Y., Shayesteh, F. y Do, H. V. (2021). Social media and environmental activism: Framing climate change on Facebook by global NGOs. Science communication, 43(1), 91-115. https://doi.org/10.1177/107554702097164

Wang, Y. y Yang, Y. (2020). Dialogic communication on social media: How organizations use Twitter to build dialogic relationships with their publics. Computers in Human Behavior, 104, 106183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.106183

We are social y Hootsuite. (2022). Digital 2022 global overview report. https://bit.ly/44daNfe

Xifra, J. y Grau, F. (2010). “Nanoblogging PR: The discourse on public relations in Twitter”. Public relations review, 36(2), 171-174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.02.005

Xifra, J. (2010). Relaciones públicas, empresa y sociedad. Una aproximación ética. Editorial UOC.

CONTRIBUTIONS OF AUTHORS, FUNDING, AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Contributions of the authors:

Conceptualization: Claro-Montes, Cecilia, Aránzazu-Ferruz-González, Sonia, and Catenacci-Martín, José-Ignacio. Validation: Claro-Montes, Cecilia, Aránzazu-Ferruz-González, Sonia, and Catenacci-Martín, José-Ignacio. Formal analysis: Claro-Montes, Cecilia, Aránzazu-Ferruz-González, Sonia, and Catenacci-Martín, José-Ignacio. Data curation: Claro-Montes, Cecilia, Aránzazu-Ferruz-González, Sonia, and Catenacci-Martín, José-Ignacio. Original draft preparation: Claro-Montes, Cecilia, Aránzazu-Ferruz-González, Sonia, and Catenacci-Martín, José-Ignacio. Writing - Review and Editing: Claro-Montes, Cecilia, Aránzazu-Ferruz-González, Sonia, and Catenacci-Martín, José-Ignacio. Visualization: Claro-Montes, Cecilia, Aránzazu-Ferruz-González, Sonia, and Catenacci-Martín, José-Ignacio. Supervision: Claro-Montes, Cecilia, Aránzazu-Ferruz-González, Sonia, and Catenacci-Martín, José-Ignacio. Project administration: Claro-Montes, Cecilia, Aránzazu-Ferruz-González, Sonia, and Catenacci-Martín, José-Ignacio. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript: Claro-Montes, Cecilia, Aránzazu-Ferruz-González, Sonia, and Catenacci-Martín, José-Ignacio.

Funding:This research did not receive external funding.

AUTHORS

Cecilia Claro Montes

University of the Andes, Chile.

Ph.D. in Communication, Master in Business Administration, and Journalist, University of the Andes. Associate Professor in the area of Institutional Communication, Faculty of Communication.

Índice H: 5

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3428-0616

Scopus ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId= 57203534556

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=BqBjxd0AAAAJ&hl=es&oi=ao

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Cecilia-Claro

Sonia Aránzazu Ferruz González

International University of La Rioja.

Ph.D. in Information Sciences from the Complutense University of Madrid, Master's in Communication and Political Management, and Bachelor's in Advertising and Public Relations from the same university. Her research focuses on organizational reputation and digital communication. Bilingual lecturer in English for undergraduate and postgraduate programs at various universities. She has over 17 years of experience as a consultant in strategic communication for large companies. Reviewer for various scientific journals. Member of the Spanish Association of Communication Researchers (AE-IC).

Índice H: 4

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4238-5717

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=q2YQQsEAAAAJ&hl=es&oi=ao

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Sonia-Aranzazu-Ferruz-Gonzalez

Academia.edu: https://independent.academia.edu/SoniaFerruz

José Catenacchi

Central University, Chile. Doctoral student in Communication at the University of the Andes, Chile. Journalist, Bachelor in Social Communication from the University of Arts, Sciences, and Communication (UNIACC). Master's in Corporate Communication and Sustainability from Andrés Bello University.

Orcid ID: https://doi.org/0000-0003-1022-2304

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=SitqgNEAAAAJ&hl=es

Related articles

Almansa, A. y Castillo, A. (2017). Uso de las redes sociales en las empresas españolas, en Arévalo Martínez, R. y Rebeil Corella, M. (Coords.) Responsabilidad social en la comunicación digital organizacional (121-142). Tirant Humanidades, Universidad Anáhuac México y Red Internacional de Investigación y Consultoría en Comunicación.

Arévalo-Martínez, R. I. y Ortiz-Rodríguez, H. (2019). Comunicación organizacional web de la ética en las organizaciones del tercer sector. Profesional de la información, 28(5). https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2019.sep.22

Arévalo Martínez, R. I. y Ortiz, H. (2018). Análisis de modelos de relaciones públicas en Facebook de las organizaciones del tercer sector de México, Chile, Inglaterra y España/Analysis of public relations models of the third sector organizations from Mexico, Chile, England and Spain using Facebook. Revista Internacional de Relaciones Públicas, 8(15), 85-106. https://doi.org/10.5783/revrrpp.v8i15.520

Abitbol, A. y Lee, S. Y. (2017). Messages on CSR-dedicated Facebook pages: What works and what doesn’t. Public Relations Review, 43(4), 796-808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2017.05.002

Balas Lara, M. (2010). La gestión de la comunicación en el Tercer Sector. Análisis de la imagen percibida de las organizaciones del Tercer Sector [Tesis doctoral, Universidad Jaume I]. https://www.tesisenred.net/handle/10803/384631

Berceruelo, B. (2016). Planificar en Internet. Online u offline: Solo comunicación Empresarial. En B. Berceruelo (coord.), Comunicación empresarial, (281- 283). Madrid: Estudio de Comunicación.

Blanco-Morett, Á., Tornay Márquez, M., Barranquero Carretero, A., Calvo, D. y Candón-Mena, J. (2022). Comunicación, redes sociales y Tercer Sector. Frente a la euforia tecnológica, los espacios de cooperación. En R. Cantero Medina (Coord.), Una comunicación para el cambio social desde entornos digitales: para mejorar el impacto social de los agentes andaluces de la cooperación, (pp. 11-27). BATÁ-Centro de Iniciativas para la Cooperación. http://bit.ly/43vNADO

Buitrago, A. y Martín García, A. (2021). Community managers en Instagram: la labor de las Relaciones Públicas de las marcas en el universo de las redes sociales. Sphera Publica, 2(21), 172-197. https://sphera.ucam.edu/index.php/sphera-01/article/view/427

Castillo Esparcia, A., Krohling-Kunsch, M. y Furlan-Haswani, M. (2017). Prácticas comunicativas y perspectivas para el cambio social en las organizaciones no gubernamentales (ONGs) en España y Brasil. Organicom, 14(26), 147-166.

https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2238-2593.organicom.2017.139364

Ihm, J. (2019). Communicating without nonprofit organizations on nonprofits’ social media: Stakeholders’ autonomous networks and three types of organizational ties. New Media y Society, 21(11-12), 2648-2670. https://doi.org/10.1177/146144481985480

Lai, C. H. y Fu, J. S. (2021). Humanitarian relief and development organizations’ stakeholder targeting communication on social media and beyond. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 32, 120-135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-020-00209-6

Meza Orellana, J. L. (2015). Facebook como herramienta de marketing/comunicación para la atracción de estudiantes internacionales: un análisis de Chile y España. Doxa Comunicación, 21, 55-77. https://doi.org/10.31921/doxacom.n21a3

Shoai, A. (2020). Diálogo entre organizaciones y públicos en la era digital: la “promesa incumplida” de los nuevos medios y el discurso de la consultoría en España. Profesional de la información, 29(3). https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.may.21

Sun, R. y Asencio, H. D. (2019). Using social media to increase nonprofit organizational capacity. International Journal of Public Administration, 42(5), 392-404. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2018.1465955

Zeler, I. (2021). Comunicación interactiva de las empresas chilenas en Facebook: un estudio comparativo con las empresas latinoamericanas. Obra digital: Revista de Comunicación, 20, 15-28. https://raco.cat/index.php/ObraDigital/article/view/385595.

Zhao, X. y Chen, Y. R. R. (2022). How brand-stakeholder dialogue drives brand-hosted community engagement on social media: A mixed-methods approach. Computers in Human Behavior, 131, 107208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107208

Zabala-Cia, O., Lorenzo-Sola, F. y González-Pacanowski, T. (2022). Interactividad en redes sociales para crear relaciones de confianza: ayuntamientos de navarra en tránsito. Revista de Ciencias de la Comunicación e Información, 27, 23-42 https://doi.org/10.35742/rcci.2022.27.e246

Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 82 https://doi.org/10.4185/rlcs-2024-2197

![]()

![]()

![]()