REVISTA LATINA DE COMUNICACIÓN SOCIAL. ISSN1138-5820

Validación de instrumento sobre exposición a discursos de odio de comunidades migrantes en el ecosistema mediático chileno: resultados preliminares

Validation of an instrument on exposure of migrant communities to hate speech in the Chilean media ecosystem: preliminary results

Validación de instrumento sobre exposición de comunidades migrantes a discursos de odio en el ecosistema mediático chileno: resultados preliminares

Nairbis Sibrian. Universidad del Desarrollo. Chile. n.sibrian@udd.cl

Amaranta Alfaro. Universidad Alberto Hurtado. Chile. aalfaro@uahurtado.cl

Juan Carlos Núñez. Universidad del Desarrollo. Chile. juan.nunez@udd.cl

This publication was funded by the Research and Doctoral Vice-Rectory of the Universidad del Desarrollo, Internal Contest, Project 23400185, March to December 2023.

How to cite this article:

Sibrian, Nairbis; Alfaro, Amaranta, & Núñez, Juan Carlos (2024). Validation of an instrument on exposure of migrant communities to hate speech in the Chilean media ecosystem: preliminary results [Validación de instrumento sobre exposición a discursos de odio de comunidades migrantes en el ecosistema mediático chileno: resultados preliminares]. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 82, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.4185/rlcs-2024-2226

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Research reports an increase in the forms of cyber hate towards migrant groups in digital contexts. However, few tools have been developed to collect the experiences of those who face such aggression. Methodology: The objective is to validate an instrument designed to assess the extent of exposure to hate speech. Additionally, it aims to examine the consequential impact on the engagement and involvement of migrant communities within the media landscape of Chile. The Delphi method, incorporating expert judgment and cognitive interviews, is implemented in this study. A meticulously crafted questionnaire comprising 26 items is applied to a pilot sample of 453 migrants residing in Chile, 51% of whom are between 30 and 59 years old, 58% are female and 60% come from Venezuela. Results: A Cronbach's Alpha of 0.95 is reached and it is found that 62% of respondents have received hate messages through Instagram (56%) and Facebook (45%), linked to their nationality (33%) and under the framing of security (43%), experiencing discomfort (53%) and hopelessness (56%). Consequently, 41% "sometimes" deleted media accounts from their digital information diet and only 7% "frequently" participate in media environments. Discussion: It is warned that cyber hate towards migrant people could produce disinformation, by news avoidance, and affect the media participation of these communities. Conclusions: A validated questionnaire was acquired to gather insights into the exposure of migrants when confronted with hate speech and its possible effects.

Keywords: hate speech; migration; Delphi method; instrument validation; Chile.

RESUMEN

Introducción: Investigaciones advierten un aumento de las formas de ciberodio hacia grupos migrantes en contextos digitales. Sin embargo, escasas herramientas relevan la experiencia de quienes enfrentan tales agresiones. Metodología: El objetivo es validar un instrumento diseñado para recoger la exposición a discursos de odio, así como los efectos en la participación de comunidades migrantes en el ecosistema mediático chileno. Se recurre al método Delphi, mediante juicio de expertos, así como entrevistas cognitivas. El cuestionario está compuesto por 26 ítems y es aplicado a una muestra piloto de 453 personas migrantes en Chile, de las cuales un 51% se ubica en el rango etario de 30 a 59 años, 58% se identifica con el género femenino y el 60% proviene de Venezuela. Resultados: Se alcanza un Alpha de Cronbach de 0.95 y se constata que un 62% de los encuestados ha recibido mensajes de odio a través de Instagram (56%) y Facebook (45%), vinculados a su nacionalidad (33%) y bajo el encuadre de seguridad (43%), experimentando incomodidad (53%) y desesperanza (56%). En consecuencia, un 41% “a veces” elimina cuentas de medios de su dieta informativa digital y sólo un 7% participa en entorno mediáticos “frecuentemente”. Discusión: Se observa que el ciberodio hacia personas migrantes podría producir desinformación, por evitación noticiosa, e incidir en la participación mediática de estas comunidades. Conclusiones: Se obtiene un cuestionario validado para recoger la exposición de personas migrantes a discursos de odio y sus posibles efectos.

Palabras clave: discurso de odio; migración; método Delphi; validación de instrumento; Chile.

1. INTRODUCTION

During the last decade, the rate of human mobility in Latin America and the Caribbean has increased by 66%, with more than 40 million people residing outside their countries of birth (PNUD, 2019). Consequently, various international agencies (PNUD, 2019; OIM, 2020) warn that countries with better development indexes become recipients of migration, posing challenges in terms of economic growth and governance (PNUD, 2019). Likewise, there are situations of humanitarian crisis that have made migration in the region massive, as is the case of the Venezuelan population (OIM, 2020).

In this context, Chile is becoming a recipient country of migration (Soto-Alvarado et al., 2022) whose difference with the migratory flows of the 1990s lies in the number and diversity of origins of human mobility (Roessler et al., 2022). According to the latest estimate of the migrant population by the National Institute of Statistics and the National Migration Service (INE and SNM, 2022), the foreign community in Chile would be 1,482,390 people on December 31, 2021, representing 7.5% of the country's total inhabitants. Out of this population, 79.4% comes from Latin American countries: Venezuela (30%), Peru (16.6%), Haiti (12.2%), Colombia (11.7%) and Bolivia (8.9%) (INE and SNM, 2022).

The National Migration Survey (BM and SNM, 2022) revealed that the majority of migrants arrived in Chile during 2018, are concentrated in the 18-39 age group and come from countries in the region. The Latin American migratory flow to Chile comprises four phases: a "historical" one until 2002, a "low" period until 2010, another "intermediate" one extending to 2014 and, finally, a "boom", starting in 2015, when the inflow of migrants per year exceeds 200,000 people (Méndez, 2019).

Such stages involve social transformations ranging from a perspective of openness to a threatening view of migration, enhanced by official speeches and press coverage (Dammert and Erlandsen, 2020) under the idea of "invasion" (Doña-Reveco, 2022). Surveys by the Chilean Center for Public Studies (CEP, 2019, 2022) place migration among the main problems perceived by the local population (13%) and indicate that 61% are in favor of prohibiting the entry of migrants. Likewise, another study on the perception of migration in Chile (CENEM, 2021) indicates that 52.7% of those consulted consider that the migration crisis affects citizen security and 62.1% consider appropriate the use of the armed forces to control it.

On the other hand, the survey "Plaza Pública" (CADEM, 2023) shows that 77% of people surveyed consider that the arrival of immigrants is negative (21 points more than in October 2021), 86% agree with closing the borders, 73% think that those who enter in an irregular manner should be expelled and 87% agree that undocumented immigrants should be detained. From the perspective of the migrant population, the survey "Migrant Voices" (SJM, 2021) revealed that 30% of the people surveyed perceive conflict between Chileans and foreigners, which is also reflected in the motivations for return among migrant groups (Mixed Migration Centre, 2022), as well as in the National Migration Survey (SNM, 2022), where 30% of those consulted indicate having suffered discrimination because of their nationality.

These surveys have allowed the development of a statistical index of relational inclusion of migrants (Roessler et al., 2022), finding that time in the country, having experienced discrimination and having support networks are key factors in the experience of exclusion. The study highlights the prevalence of low inclusion scores in migrants without residence permits and those born in Haiti.

Regarding the role of the media and social networks, the report Corrientes Subalternas (Callís and Gómez, 2023) revealed that the Chilean press links migration with crime in its coverage, while conversations in social networks associate it with the deficiency of public services. In this regard, empirical research has analyzed the informative treatment of migrant groups in the Chilean press, finding a differentiated approach according to country of origin (Valenzuela-Vergara, 2019) and types of platforms or media (Scherman and Etchegaray, 2021), which not only reproduces xenophobic attitudes (Nesbet et al., 2021), but would have an impact on the practices of audiences (Scherman et al., 2022), on intercultural interactions online and offline (Bonhomme and Alfaro, 2022b), generating exclusion in areas of the public sphere such as civic participation (Pérez et al., 2021).

All these data arouse interest in the repercussions of certain communication dysfunctions, such as cyberhate, on the informational practices of migrant communities themselves in the digital environment. In this sense, this research proposes an instrument that seeks to collect the experience of xenophobia in social networks, expressed through hate speech, together with the effects of this perception on attitudes and practices of migrant communities in the media ecosystem.

The study aims to complement research on migration and media consumption (Etchegaray and Correa, 2015), phenomena such as selective exposure (Gil de Zúñiga et al., 2012; Wojcieszak and Garrett, 2018), as well as participation (Pérez et al., 2021) of migrants in media and social networks. Next, the state of the art of the phenomenon is presented along with the main studies on migration in Chile, then moving on to the theoretical background, to continue with the design of the instrument. Subsequently, the results of the validation process and the first descriptive results are presented. Finally, the relationship between exposure to hate speech and participation is investigated.

1.1. Studies on media and migration in Chile: State of the art

In Chile, the political discourse of elites (Correa, 2018; Durán and Thayer, 2017) and the population's perceptions of migration (Cirano et al., 2017; Navarrete, 2017) have been analyzed. Most of these studies agree that there are differentiated frameworks of treatment towards migrant communities, which include forms of racism (Tijoux, 2016) and affect coexistence (Bonhomme, 2021).

Specifically, studies on media frames have found that the representation of migrant groups reinforces prejudices and negative attitudes (Scherman et al., 2022), with a greater bias when representing Latin American groups (Valenzuela-Vergara, 2019). These differentiations contribute with racialization processes (Murji and Solomos, 2005; Stefoni and Brito, 2019) extensible to digital platforms and media.

Therefore, the media ecosystem (Scolari, 2015) poses a series of ethical challenges in terms of information on migration, as it is prone to phenomena such as misinformation (Olmo and Romero, 2019) and digital racism (Bonhomme and Alfaro, 2022a) that could affect intercultural coexistence (Bonhomme and Alfaro, 2022b).

A recent study revealed that about a hundred migration misinformation have been verified by fact-checking platforms between 2018 and 2022 in Chile (Sibrian, 2023). The results show that the discourse has shifted from being located in the economic impact to one focused on security threats when receiving migrants.

Another research noted that between 2018 and 2020 there were 1,453,884 tweets associated with migration in Chile, of which about 211,780 were discriminatory. Likewise, between January 2021 and February 2022, a total of 91,944 xenophobic mentions were recorded (Rolle et al., 2022).

However, there are no studies on how these informational distortions are perceived by the migrant population or how it impacts their digital practices, since most studies are focused on media representation or on the exercise of suffrage (Pérez et al., 2021).

1.2. From Consumption to participation: Theoretical aspects

Since the turn to audiences, with the limited effects model, communication theories focus on subjects and their media use (Donstrup, 2018). Therefore, the leading question is no longer what the media do to people but what people do with the media, i.e., how they encounter the content and how it influences attitudes and behaviors.

In response to these questions, on the one hand, there is the model of uses and gratifications that, proposed by Eliu Katz in the 1960s, explains media consumption as practices aimed at satisfying needs (Krcmar, 2017) and whose applications have been adapted to the digital environment (Hossain et al., 2019). On the other hand, there is media exposure theory, which aims to understand how citizens encounter information and what its effects are.

The theory of media exposure was linked, in its beginnings, to the hypothesis of cognitive dissonance coming from psychology, which recognizes predispositions of subjects when consuming media (Valera-Ordaz, 2018) and seeks to explain the behavior of avoiding information inconsistent with their opinions (Ramírez-Dueñas and Vinuesa-Tejero, 2020). An update of this proposal derives in the term "echo chamber", which explains the informational isolation of users when seeking or avoiding content according to ideology or group membership (Cinelli et al., 2020).

Therefore, the category media use is key (Scherer, 2017) to understand how, when, and why people spend time on media content (Phua et al., 2017), recognizing that exposure to media can vary in intensity and quality. From this perspective, media consumption could be determined by both social identities and characteristics of the media system (Arendt et al., 2019).

Research reveals how people are selectively exposed to news, according to ideological or cognitive predispositions, finding a relationship between news consumption and an unfavorable perception towards migration (Gil-de-Zúñiga et al., 2012). However, changes in the digital environment have drawn attention to content flows (Thorson and Wells, 2015), generating arguments in favor of a-) the power of individuals to design their own information environment, b-) the increased capacity of strategic agents to guide messages and c-) the distribution of content by algorithms.

Incidental consumption of information (Gil-de-Zúñiga et al., 2017) and news avoidance (Fletcher and Nielsen, 2019) also become frequent as phenomena, which complexifies the possibility of choice, while later work refutes the cognitive dissonance explanation, suggesting hypotheses based on criteria of quality, perceived credibility, and relevance (Metzger et al., 2020).

Although many studies on exposure establish that people prefer sources of information that confirm their views (Valera-Ordaz, 2018), other research proposes that people lean towards sources perceived as more balanced or with less bias, evaluated under quality criteria such as: data reliability or balance in coverage (Metzger et al., 2020).

Studies on media and migration indicate that media content can influence social perceptions. In this regard, Van Dijk (2012) argues that a negative image of "others" and a positive image of "us" are often generated. These are representations constituted by strategies of legitimization and delegitimization, which represent migrant collectives as "others" (Ivanova et al., 2022), according to nationalities and contexts (Ivanova and Jocelin-Almendras, 2022), emphasizing racial markers (Tijoux, 2016; Mercado and Figueiredo, 2023).

Lawlor and Tolley (2017) identify six specific frameworks of migration in the media: economy, ethnicity, rights, security, services, validity, or legitimacy, which would influence the perception and participation of audiences, the latter understood as actions that allow the creation and expression in media spaces (Arriagada et al., 2022).

1.2.1. Hate speech as a phenomenon

The Online Hate and Harassment reports of the Anti-Defamation League (2020, 2021) warns of an increase in forms of cyber-hate in social networks targeting migrants (Amores et al., 2021), enhanced by the expansive conditions of social networks and global crises (Arcila-Calderon et al., 2022).

According to Hernández and Fernández (2019), 30% of the disinformation distributed on Facebook portals in Spain are anti-migration. In this regard, Urbán (2019) points out that migrants are the "scapegoats of the economic and systemic crisis" (p.13) as they seek to criminalize and normalize hatred towards this population (Camargo, 2021). Therefore, hate speeches about migration are deliberately disseminated as disinformation strategies (Grimes, 2020) that contribute to the exclusion of migrant collectives (Schäfer and Schadauer, 2019; Zhang et al., 2019).

Hate speech is not a new phenomenon, it is a radical way of expressing rejection that, however, might have found in digital platforms an ideal environment to spread (Amores et al., 2021), thanks to the anonymity (Erjavec and Kovačič, 2012) and the low moderation (Bonhomme and Alfaro, 2022b) of these spaces. Thus, the repercussions of hate speech have intensified, both at the personal and social level (Ramírez-García et al., 2022), crossing the virtual border and provoking offline actions (Bonhomme and Alfaro, 2022b).

Thus, Miró (2016) differentiates explicit or direct hate speech, which instigates physical violence and can be considered a crime, from the more subtle one that, although it involves offense and rejection of certain individuals or vulnerable groups, remains within the margins of freedom of expression. Under this precept, he categorizes hate speech as: 1) those that incite physical violence and 2) those that constitute moral violence.

In turn, Gagliardone et al. (2015) understand as hate speech all types of expressions that incite discrimination or violence, whether for reasons of racial hatred, xenophobia, sexual orientation, or other forms of intolerance. The term even extends to those expressions that may contribute to the creation of a climate of hostility and that may lead to discriminatory acts. This last definition is the one that will be considered relevant for the development of the instrument in this research, more specifically racial hatred considered the most common form of cyber-hate (Douglas et al., 2005).

2. OBJECTIVES

This study investigates how is the exposure to hate speech of migrant communities in the Chilean media ecosystem? Also, what is the relationship of this exposure with participation in media and social networks? Finally, how can these aspects be explored through a valid and reliable instrument?

Therefore, the main objective is to design and validate an instrument that collects the exposure to hate speech and participation of migrant communities in the Chilean media ecosystem. While the specific objectives are a-) to identify the relevant dimensions and indicators for the elaboration of the questionnaire, b-) to establish the content validity and convergence of the dimensions and indicators, c-) to explore the exposure to hate speech in media and social networks experienced by migrant communities, d-) to investigate the relationship between exposure to hate speech and participation in media and social networks and, finally, e-) to determine the reliability of the designed instrument.

3. METHODOLOGY

A quantitative approach (Hernández et al., 2014) based on a survey (Cea D'Ancona, 2004) was chosen as a technique to collect practices and perceptions of migrant communities regarding hate speech in the media ecosystem, since it allows visualizing trends and patterns.

Then, a mixed approach with sequential stages of design, construction and validation was used to develop the instrument. The design of the questionnaire was carried out using the Delphi method (López, 2018), which consists of requesting the evaluation of the instrument to an expert panel, who reach consensus on the relevance and validity of its dimensions. Therefore, the construction and validation of the questionnaire had five phases: 1-) Creation and establishment of the expert commission; 2-) Design of the questionnaire; 3-) Evaluation of experts; 4-) Cognitive evaluation interviews; and 5-) Implementation of the pilot.

The research had three types of sampling: a-) sample of experts for the evaluation of the instrument, b-) group of migrants for cognitive interviews and c-) pilot sample to validate the instrument. The first was selected by non-probabilistic sampling and was composed of 8 (eight) researchers from various disciplines (anthropology, political science, communications, and social work), belonging to public and private, national, and international universities, such as: Universidad de Chile, Universidad Autónoma de Chile, Universidad Diego Portales, and Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, from Spain. The second corresponds to 6 migrants in Chile, over 18 years of age, of various nationalities: Venezuela (2), Peru (1), Ecuador (1), Mexico (1) and Colombia (1). Finally, the third consisted of 453 migrants over 18 years of age, residents in Chile, with 0.99 confidence and 0.01 probability of error, according to the sampling standard for pilot studies (Viechtbauer et al., 2015).

For the development of the dimensions, the following concepts were considered: fake news (Olmo and Romero, 2019) and hate speech (Bustos et al., 2019), selective exposure (Wojcieszak and Garrett, 2018), selection criteria (Metzger et al., 2020), media frames associated with migration (Lawlor and Tolley, 2017) and forms of participation in social networks (Arriagada et al., 2022).

3.1. Instrument

Thus, the questionnaire proposal is based on five (5) dimensions, with five (5) indicators in each one, starting with six (6) sociodemographic identification items and 20 items corresponding to the study dimensions, distributed as follows:

Chart 1. Dimensions, items, and indicators of the instrument

|

Dimensions |

Items |

Indicators |

|

2. Media consumption |

7; 8; 9; 10; 11 |

2.1 Frequency of use of media platforms |

|

2.2 Level of motivation in information consumption |

||

|

2.3 Level of interest in current topics |

||

|

2.4 Level of valuation of social media as information platforms |

||

|

2.5 Frequency of reception of misinformation |

||

|

3. Exposure to hate speech |

12; 13; 14; 15; 16 |

3.1 Frequency in the reception of hate speech on media platforms |

|

3.2 Frequency of perception of discrimination on media platforms |

||

|

3.3 Frequency of perceived xenophobia on media platforms |

||

|

3.4 Frequency of negative attitudes towards hate speeches |

||

|

3.5Frequency of negative emotions in hate speeches |

||

|

4. Effects of exposure to hate speeches |

17; 18; 19; 20; 21 |

4.1 Degree of importance of media selection criteria |

|

4.2 Frequency of media avoidance |

||

|

4.3 Frequency in media elimination |

||

|

4.4 Degree of importance of media elimination criteria |

||

|

4.5 Degree of relevance in the reasons for media elimination |

||

|

5. Forms of media participation |

22; 23; 24; 25; 26 |

5.1 Frequency of media and social network participation |

|

5.2 Degree of likelihood of media participation |

||

|

5.3 Degree of probability in public activities |

||

|

5.4 Frequency of participation in support groups |

||

|

5.5 Level of motivation to belong to support groups |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Each questionnaire item offers response modalities under a five-category Likert scale indicating frequency of perception, consumption, and practices (1. Never, 2. Almost never, 3. Sometimes, 4. Frequently, 5. Very frequently), degree for importance, relevance, and probability (1. Not at all, 2. Little, 3. Enough, 4. Quite a lot, 5. Very much) and level for motivation, valuation, and interest (1. Very low, 2. Low, 3. Medium, 4. High and 5. Very high).

The design of the instrument had two stages of adjustment, in order to respond to the particular context of the study. The first consisted of contrasting the literature prior to the development of the dimensions and their categories, with recent local cases and studies (see Bonhomme and Alfaro, 2022a-b; Ivanova et al., 2022; Scherman and Etchegaray, 2021; Scherman et al., 2022). A second stage consisted of conducting cognitive interviews with six (6) migrants, as will be detailed in the procedure section.

Although the instrument is relevant to collect the perception of migrant communities in the face of hate speech, it does not capture the way in which this speech reaches migrants nor the coping strategies that are developed.

3.2. Procedure

The evaluation of the instrument was carried out asynchronously, therefore, the list of dimensions, indicators and questions that would make up the questionnaire was sent to the expert judges via e-mail, together with a validation guide with the following variables: a-) Relevance of the dimensions and indicators, b-) Degree of appropriateness of the topics, c-) Structure, d-) Comprehensiveness of questions, e-) Presentation format. In this way, the evaluators assigned scores to each question of the questionnaire and established indices of comprehensiveness and relevance, the averages of which will be detailed in the results.

The design of the instrument was carried out between March and May 2022, while the peer evaluation took place between June and August of the same year. Likewise, after the construction and validation by expert judgment of the questionnaire, cognitive interviews were conducted with six (6) migrants to verify the understanding of the questions and improve their wording, if necessary, which were carried out during September 2022 and lasted 90 minutes each, allowing for the rewording of 11 questions in both form and content, as shown in the following chart:

Chart 2. Changes to the form and content of the instrument

|

Items |

Type of Change |

Results |

|

|

Form |

Content |

||

|

7 |

To change order in answer choices |

It is suggested to add podcast |

Accepted |

|

8 |

- |

It is suggested to add the option "not reported" |

Accepted |

|

9 |

To avoid subsections in the wording |

It is suggested to add other answer alternatives |

Accepted |

|

10 |

To extend the date range of the question |

To extend the range of media and platforms |

Accepted |

|

13 |

To change the question to active form |

- |

Accepted |

|

14 |

To change the question to active form |

- |

Accepted |

|

16 |

- |

To differentiate between attitudes and emotions |

Accepted |

|

17 |

- |

To add the option of "company or information chain" |

Accepted |

|

18 |

- |

To add the alternative of "not applicable" or "not used" |

Accepted |

|

19 |

- |

To add the alternative of "not applicable" or "no use" |

Accepted |

|

23 |

- |

To change boycott to blocking |

Accepted |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

3.3. Implementation to the pilot group

The electronic and self-administered survey was pilot-tested between October 2022 and March 2023 (six months). During this period, the survey was available on the web portals of migrant organizations such as the Catholic Migration Institute (INCAMI) and the Program for the Reception and Attention to Migrants (PIAAM) of the Universidad del Desarrollo. It was also sent by mail to databases of migrant organizations in Chile with which we have contact. Likewise, the research team repeatedly attended events and activities of the aforementioned organizations, and by means of a QR code asked the subjects of the study to respond to the instrument.

3.4. Pilot sample

The participants in the study are 453 migrants, over 18 years of age, belonging to the following age groups: 45% from 18 to 29, 51% from 30 to 59 and 5% over 60 years of age; gender: 58% female, 41% male and 1% other; residents in various regions of Chile: 74% in the Metropolitan Region, 13% in the Central Area, 8% in the Northern Area and 6% in the Southern Area. The majority have been living in Chile for more than 5 years (65.3%) and come mainly from Venezuela (62%) along with other countries, as shown in Chart 3. Although there is an overrepresentation of Venezuelans in the sample, this responds to the fact that this community is the largest group of migrants in Chile, representing 41% of the migrant population in Chile (Casen, 2021) and being the second country in the region with the largest number of Venezuelan migrants after Peru (Banco Mundial, 2023).

Chart 3. Distribution of the sample by country

|

Country |

n |

% Total |

|

Argentina |

21 |

4,64% |

|

Bolivia |

11 |

2,43% |

|

Colombia |

44 |

9,71% |

|

Ecuador |

9 |

1,99% |

|

Haiti |

10 |

2,21% |

|

Other |

52 |

11,48% |

|

Peru |

25 |

5,52% |

|

Venezuela |

281 |

62,03% |

|

Total |

453 |

100,0% |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

4. RESULTS

The results are organized according to the validation stages of the instrument. First, the validity by expert judgment is presented, according to the indicators of relevance and comprehensiveness. Then, the validity according to Cronbach's Alpha is presented. Likewise, the main results of the pilot application are presented, expressed by means of the average of the scores from 1 to 5 (Likert scale) for each item, concerning the degree, level or frequency of a given indicator. However, some specific items are disaggregated and expressed in percentages (e.g. frequency in types of media, topics, or messages).

4.1. Validity by expert review and judgment

To validate the instrument, by expert judgment, a comprehensiveness index (CI) and a relevance index (RI) were established for each item, expressed on a scale from 1 to 100, where 80 is the cut-off average to consider them final, from 60 to 79 modifiable and less than 60 in re-wording. Only one round of validation was carried out since, in the first evaluation, most of the values corresponding to each item were above 80, as were the RI and CI averages in each dimension, as shown in the chart below:

Chart 4. Validity index for each dimension/item according to RI/CI

|

Items |

Media Consumption |

Exposure to Hate Speech |

Effects of Exposure to Hate Speeches |

Forms of Media Participation |

||||

|

Crititerion/Evaluator |

RI |

CI |

RI |

CI |

RI |

CI |

RI |

CI |

|

Evaluator 1 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

96 |

96 |

|

Evaluator 2 |

100 |

73,6 |

100 |

90 |

100 |

96 |

100 |

96 |

|

Evaluator 3 |

100 |

90 |

91 |

91 |

95 |

95 |

100 |

100 |

|

Evaluator 4 |

98 |

92 |

88 |

88 |

100 |

94 |

100 |

88 |

|

Evaluator 5 |

96 |

100 |

96 |

100 |

98 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

Evaluator 6 |

90 |

80 |

95 |

86 |

95 |

78 |

93 |

91 |

|

Evaluator 7 |

92 |

82 |

90 |

85 |

100 |

88 |

100 |

90 |

|

Evaluator 8 |

100 |

100 |

98 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

98 |

|

Total Average |

97,0 |

89,7 |

94,8 |

92,5 |

98,5 |

93,9 |

98,6 |

94,9 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Only two questions were reformulated in their wording, pertaining to the dimensions of news consumption and selective exposure, which were sent again to evaluators 2 and 6, who awarded scores below 80 points to these dimensions: 73.6 and 78, respectively. However, in a second review these dimensions exceeded the cut-off score.

4.2. Validity by Cronbach's Alpha

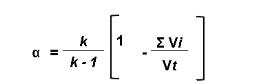

To analyze the reliability of the instrument, Cronbach's Alpha coefficient was used as a measure of internal consistency, which refers to the degree to which the items of a scale correlate with each other and is considered acceptable when it is between 0.70 and 0.90 (González and Pazmiño, 2015). In this case, Cronbach's Alpha was calculated both for the instrument in general and for each of its dimensions, based on the following formula:

Cronbach's Alpha Formula

The coefficient obtained is 0.95, which corresponds to a high reliability value as shown in the following table:

Chart 5. Cronbach's Alpha Results

|

Symbol |

Descrption |

Result |

|

α |

Cronbach’s Alpha |

0,952436727 |

|

k |

Number of items |

141 |

|

Vi |

Variance each item |

259,1806135 |

|

Vt |

Variance in total |

4.771,529329 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

However, when reviewing the dimensions separately, the coefficients are different. This occurs because the formula for calculating the coefficient includes the number of items as a parameter; therefore, the overall instrument is more consistent than each dimension, as shown in the chart below:

Chart 6. Cronbach's Alpha by instrument dimension

|

N° |

|

Dimension |

Cronbach's Alpha |

|

1 |

|

Sociodemographic Data |

-* |

|

2 |

|

Media Consumption |

0.88 |

|

3 |

|

Exposure to Hate Speech |

0.91 |

|

4 |

|

Effects of Exposure to Hate Speech |

0.86 |

|

5 |

|

Forms of Media Participation |

0.92 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

4.3. Pilot results by dimension

The results obtained offer a first descriptive-correlational diagnosis of media consumption, exposure to hate speech, selective exposure to information and the relationship between exposure and media participation in migrant communities in Chile. The basic descriptive data are presented according to the average scores obtained in each item, according to a Likert scale. However, when the response options are disaggregated according to the typologies consulted, frequency data expressed in percentages are obtained in some relevant cases.

4.3.1. Media Consumption

Regarding media consumption, it can be noted that there is a moderately frequent use (2.5) of digital platforms and social networks, as well as an average valuation of these as sources of information (2.6), as shown by the mean and standard deviation indices. The high level of motivation for information related to migration (3.2) and interest in current affairs (3.7) stands out in the sample consulted, who state that "sometimes" (2.3) they receive disinformation through these platforms.

Chart 7. Basic descriptors of media consumption

|

Media consumption dimension |

||||

|

Items |

Average |

Median |

Standard Deviation |

Kurtosis |

|

2.1 Frequency of use of media platforms |

2.5 |

2 |

1.4 |

-0.5 |

|

2.2 Level of motivation in the consumption of information |

3.2 |

3 |

1.2 |

-0.8 |

|

2.3 Level of interest in current issues |

3.7 |

4 |

1.1 |

-0.7 |

|

2.4 Level of valuation of social media as information platforms |

2.6 |

3 |

1.4 |

-0.4 |

|

2.5 Frequency in the reception of misinformation |

2.3 |

2 |

1.5 |

|

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

When reviewing the frequencies of the answer choices, according to the type of media in each item, the results indicate that the migrant population in Chile is mainly informed by Instagram (60%) and "sometimes" by digital platforms of traditional media (25%). It also shows that the migrant population is interested in national news (37%), whose motivations include "being able to support other migrants" (33%). The social networks Instagram (53%) and Twitter (41%) are considered the most relevant information platforms, despite the fact that they state that they have received disinformation through them (28%).

4.3.2. Exposure to Hate Speech

Regarding exposure to hate speech in the media and social networks, the migrant population consulted indicates that "sometimes" (2.5) receives hate messages through digital news platforms. Likewise, the perception of discriminatory (3.2) and xenophobic (3.5) speeches on such platforms is also frequent, as indicated by the corresponding mean and standard deviation values. Regarding the effects at the subjective level, there is a higher frequency of negative emotions (3.2) than negative attitudes (2.9) associated with this exposure.

Chart 8. Basic descriptors of exposure to hate speech

|

Exposure to hate speech dimension |

||||

|

Items |

Average |

Median |

Standard Deviation |

Kurtosis |

|

3.1 Frequency of hate speech reception on media platforms |

2.5 |

3 |

1.6 |

-0.9 |

|

3.2 Frequency in perception of discrimination in media platforms |

3.2 |

3 |

1.3 |

-1.0 |

|

3.3 Frequency in perception of xenophobia in news platforms |

3.5 |

4 |

1.2 |

-0.7 |

|

3.4 Frequency of negative attitudes towards hate messages |

2.9 |

3 |

1.2 |

-0.6 |

|

3.5 Frequency of negative emotions when faced with hate messages |

3.2 |

3 |

1,3 |

|

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

According to the frequency of each component, within the response options of the item associated with types of media, it stands out that Instagram (56%) and Facebook (45%) are the platforms through which the migrant community has "frequently" perceived hate speeches. As for the reasons for discrimination, culture and customs stand out (25%), while xenophobia is "very frequently" linked to nationality and/or belonging to a country (33%) and under the framing of public safety (43%). As for the reaction to hate speech, discomfort prevails (53%), as well as hopelessness (56%).

4.3.3. Effects of exposure to hate speech

Regarding the type of exposure on media platforms, the consulted population gives a medium-high level of importance (3.4) to the selection criteria, expressed in the degree of "quite important" with respect to choosing the media to be consumed. Likewise, the results reveal an even higher level of importance of the elimination criteria (3.7) expressed in the answer "quite important" to eliminate media containing hate speech. Thus, there is a medium level frequency (2.3), reflected in the expression "sometimes", for media avoidance and a medium-high frequency (2.8), expressed in "frequently", for media elimination.

Chart 9. Basic descriptors of effects of exposure to hate speech

|

Effects of exposure to hate speech dimension |

||||

|

Items |

Average |

Median |

Standard Deviation |

Kurtosis |

|

4.1 Degree of importance of media selection criteria |

3.4 |

3 |

1.2 |

-0.6 |

|

4.2 Frequency of media avoidance |

2.3 |

2 |

1.5 |

-1.0 |

|

4.3 Frequency of media elimination |

2.8 |

3 |

1.1 |

-0.4 |

|

4.4 Degree of importance of media elimination criteria |

3.7 |

4 |

1.2 |

-0.4 |

|

4.5 Degree of relevance in the reasons for media elimination |

3.1 |

3 |

1.3 |

-0.9 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

These results indicate that although it is considered important to have news selection criteria, which may involve the avoidance and elimination of media due to the presence of hate speech, these measures are in a medium range, but with an increasing trend as shown by the standard deviation in the measure of media elimination. When reviewing the frequency with which these measures are taken, in each of the components, it stands out the avoidance to be informed by WhatsApp (31%) and Facebook (32%). Likewise, 41% "sometimes" have eliminated media accounts and social networks from their media consumption due to the presence of hate speeches.

4.3.4. Forms of media participation

Regarding participation in social media and networks of the migrant population, it was found that the average frequency is low (1.5) according to the categories of "never" and "almost never", as is the frequency of participation in support groups (2.0). However, the degree of probability that the persons consulted participate in social media and networks is rather medium (2.7), as is the probability that they participate in public activities (2.3). Likewise, the level of motivation to participate in support groups for migrants stands out at a medium-high level (2.8).

Chart 10. Basic descriptors of forms of media engagement

|

Forms of media participation dimension |

||||

|

Items |

Average |

Median |

Standard Deviation |

Kurtosis |

|

5.1 Frequency of participation in media and social networks |

1.5 |

1 |

1.1 |

1.9 |

|

5.2 Degree of probability of media engagement |

2.7 |

3 |

1.4 |

-1.0 |

|

5.3 Degree of probability of public engagement activities |

2.3 |

2 |

1.2 |

-0.5 |

|

5.4 Frequency of engagement in support groups |

2.0 |

2 |

1.1 |

0.0 |

|

5.5 Level of motivation to belong to support groups |

2.8 |

3 |

1.2 |

|

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

In terms of percentages, obtained from the answer choices in each item, it is noteworthy that 47% "never" participate (creation or expression) in media environments, while only 7% do so "frequently". Likewise, only 2% of the sample participates in an online support group. However, there is interest in participating in support groups to "help other migrants" (37%).

4.3.5. Relationship between exposure to hate speech and media participation

Chart 11. Relationship between exposure to hate speech and media engagement

|

Engagement |

Hate Speeches |

Total |

|

|

Not received |

Received |

||

|

1. Never |

26% |

38% |

64% |

|

2. Almost never |

4% |

10% |

14% |

|

3. Sometimes |

2% |

5% |

6% |

|

4. Frequently |

1% |

2% |

3% |

|

5. Very frequently |

0% |

1% |

1% |

|

6. Not applicable (no consumption) |

5% |

6% |

12% |

|

Total |

38% |

62% |

|

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

However, when reviewing the low percentage that "very frequently" engage (3%) in digital media environments, it is relevant that those who have received hate messages are also in the majority (2%). Therefore, the lack of media engagement, i.e., not expressing their opinion, is a generalized trend in the migrant population consulted, associated not only with the reception of hate speeches, although such reception is also a trend (62%).

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Regarding the main objective of designing and validating an instrument to collect the exposure to hate speech and engagement of the migrant community in the Chilean media ecosystem, a questionnaire was constructed and approved containing the dimensions of media consumption, perception of hate speech, type of exposure and media engagement of migrant communities.

It is an instrument validated by a panel of experts, with an average of 90 points for each dimension, whose Cronbach's Alpha was 0.95. The study describes in detail its process of development and validation, giving an account of each stage until the specific indicators for each dimension are reached. This exercise constitutes a pedagogical and clarifying contribution to the methodological design, making the decisions taken transparent.

The results obtained in the pilot implementation of the instrument, expressed on a scale of 1 to 5, indicate that there is a high level of interest in current affairs (3.7) among the migrant population, as well as a high level of motivation for information related to migration (3.2). Such data coincide with previous studies on media use in migrant population (Etchegaray and Correa, 2015) which indicate that there is a high local media consumption (90%).

However, the global nature of this result may hide differences in access to and consumption of information by nationality, since according to the National Migration Survey (SNM, 2022) the level of connectivity is high only among Venezuelan migrants (90%), while this access drops to 54% among Haitians and Bolivians. Therefore, it would be pertinent to disaggregate these results by nationality in future research.

Regarding the use of digital platforms for news consumption, this is moderately frequent (2.5) consuming mainly Instagram (60%), which is far from previous studies on media use in migrant population in Chile (Etchegaray and Correa, 2015) in which television predominated and coincides with more recent studies that reveal that 92.1% of the migrant population uses social networks for information (Roessler et al., 2022). This result reflects the wide use of digital platforms in Chile according to data from the Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2023, which indicates that WhatsApp (75%), Facebook (71%), Instagram (60%), YouTube (69%) and TikTok (39%) are the most used social networks in general and for information.

However, there is an average valuation of social networks as information platforms (2.6), as "sometimes" (2.3) they state that they receive disinformation through these platforms. In this regard, local studies have pointed out that in the last five years the cases of disinformation on migration have increased (Sibrian, 2023) contributing to the disorientation in many aspects of public life of this social group.

Likewise, there is a high perception of discriminatory (3.2) and xenophobic (3.5) speeches on digital platforms, with a medium-high level in the reception of hate speeches (2.5). It should be noted that these speeches are mainly received through Instagram (56%) and Facebook (45%), following Farkas et al. (2018), Roberts (2019) or Shepherd et al. (2015), given that these platforms benefit from the engagement generated by hate speeches, aroused by anonymity, lack of moderation and permissiveness. In turn, the results indicate that xenophobia is "very frequently" linked to nationality (33%) under the security frame (43%), which emphasizes threats to public guarantees for the admission of migrants (Lawlor and Tolley, 2017).

These results are novel as they offer an approximation to the level of exposure to hate speech of the migrant population in Chile, revealing that 62% of the population consulted has received this type of messages through social networks. This coincides with an international trend, as Hernández and Fernández (2019) argue that in Spain 30% of the disinformation distributed on social networks, are against migration and linked to security that uses hatred and xenophobia as a means of communication.

It is also unprecedented the relief of emotions associated with hate speeches in the migrant population, mainly made up of negative feelings (3.2) in which hopelessness (56%) and discomfort (53%) prevail as a reaction. In this regard, it should be noted that hate speech can have serious consequences ranging from different modes of suffering (Hun et al., 2021; Urzúa et al., 2019; Montes, 2019) to hate crimes (Müller and Schwarz, 2020).

Therefore, the population consulted considers it important to select the media they consume (3.4), that is, to determine a careful media diet. They also attach a high level of importance to media elimination criteria (3.7). They even sometimes avoid certain media (2.3) and frequently eliminate them (2.8) as strategies to protect themselves from exposure to hate speech and misinformation.

In this regard, Humanes (2019) points out that there is a tendency to news avoidance of sensitive topics, given that people prefer soft news rather than hard news (Fletcher and Nielsen, 2019). The fact that selective exposure and news avoidance are consolidated as prevalent strategies among migrants could generate news gaps. News avoidance leads to negative consequences for social cohesion among citizens (Ohme, 2021; Strömbäck, 2017), and is a problem for democracy, given that news consumption has a positive impact on citizens' knowledge of society and politics, as well as on their political engagement and participation (Scherman et al., 2013; Santana, 2016; Navia and Ulriksen, 2017). Avoiding news on a regular basis can lead to disengaged citizens and encourages polarization of opinion, at the same time it can lead to an imbalance in representative democracies (Blekesaune et al., 2012).

In total, 41% of the sample has "sometimes" deleted media accounts on social networks, which together with the fact that they are only informed by platforms such as Instagram and that, on occasions, they avoid news, is transformed into a situation prone to misinformation, which could lead to a lack of knowledge of rights and obligations that concern them as residents in the country. This is consistent with several studies on the lack of information on guarantees and freedoms of the migrant population (Roessler et al., 2022; Pérez et al., 2021).

Finally, the engagement of the migrant population in media platforms is low (1.5), as is the frequency of engagement in online support groups. In this regard, 47% never engage in the Chilean media ecosystem, while only 7% do so frequently. These data confirm the findings of the National Migration Survey (INE and SNM, 2022), which states that the immigrant population's engagement in support groups is 24%, and mainly in religious groups.

The relevance of the study lies in the fact that it is an unprecedented instrument that allows the study of hate speech from the perspective of those who receive it and its consequences. However, among its limitations is the limited heterogeneity of the sample, with the Metropolitan Region being overrepresented, due to the difficulty in reaching some regions of the national territory and certain migrant communities.

There are opportunities for future research exploring qualitative dimensions of coping strategies in the face of online hostility. Likewise, these data can contribute to the design of public policies that promote coexistence through the early detection of online violence. A replicable initiative is the first prototype created for the automatic detection of hate speech on Twitter by a group of researchers from European universities (Arcila-Calderón et al., 2021).

6. REFERENCES

Amores, J. J., Blanco-Herrero, D., Sánchez-Holgado, P. y Frías-Vázquez, M. (2021). Detectando el odio ideológico en Twitter. Desarrollo y evaluación de un detector de discurso de odio por ideología política en tuits en español. Cuadernos.info, 49, 98-124. https://doi.org/10.7764/cdi.49.27817

Anti-Defamation League (2020). Online hate and harassment. The american experience 2020. Center for Technology and Society.

Anti-Defamation League (2021). Online hate and harassment. The american experience 2021. Center for Technology and Society.

Arcila-Calderón, C., Amores, J., Sánchez-Holgado, P. y Blanco-Herrero, D. (2021). Using shallow and deep learning to automatically detect hate motivated by gender and sexual orientation on twitter in spanish. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 5(10). https://doi.org/10.3390/mti5100063

Arcila-Calderón, C., Sánchez-Holgado, P., Quintana-Moreno, C., Amores, J. y Blanco-Herrero, D. (2022). Hate speech and social acceptance of migrants in Europe: Analysis of tweets with geolocation. Comunicar, 71, 21-35. https://doi.org/10.3916/C71-2022-02

Arendt, F., Northup, T. y Camaj, L. (2019). Selective exposure and news media brands: Implicit and explicit attitudes as predictors of news choice. Media Psychology, 22(3), 526-543.

Arriagada, A., Browne, M., González, R., Salvatierra, V., Santana, L. y Velasco, P. (2022). Flujos de curatoría informativa en adolescentes. Universidad Adolfo Ibáñez.

Banco Mundial [BM] (2023). Informe sobre el desarrollo mundial 2023: Migrantes, refugiados y sociedades. Washington. https://acortar.link/re0L4x

Banco Mundial [BM] y Servicio Nacional de Migraciones [SNM] (2022). Encuesta Nacional de Migración. https://acortar.link/HleKq1

Blekesaune, A., Elvestad, E. y Aalberg, T. (2012). Tuning out the world of news and current affairs: An empirical study of Europe’s disconnected citizens. European Sociological Review, 28(1), 110-126 https://doi.org/.10.1093/esr/jcq051

Bonhomme, M. (2021). Racism in multicultural neighbourhoods in Chile: Housing precarity and coexistence in a migratory context. Bitácora Urbano Territorial, 31(1), 167-181. https://doi.org/10.15446/bitacora.v31n1.88180

Bonhomme, M. y Alfaro, A. (2022a). ‘The filthy people’: Racism in digital spaces during COVID-19 in the context of South-South migration. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 25(3-4), 404-427. https://doi.org/10.1177/13678779221092462

Bonhomme, M., y Alfaro, A. (2022b). Migración haitiana y racismo anti-negro: Las implicancias de los encuadres mediáticos en espacios públicos y digitales. Cuadernos de Teoría Social, 8(16), 86-125

Bustos, L., De Santiago, P., Martínez, M. y Rengifo, M. (2019). Discursos de odio: una epidemia que se propaga en la red. Estado de la cuestión sobre el racismo y la xenofobia en las redes sociales. Mediaciones Sociales, 1, 25-42. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6963028

CADEM (2023). Encuesta Plaza Pública. Estudios. https://cadem.cl/plaza-publica/

Callís, A. y Gómez, M. (2023). Corrientes Subterráneas. Informe 1. Universidad Central de Chile.

Camargo, L. (2021). El nuevo orden discursivo de la extrema derecha española: de la deshumanización a los bulos en un corpus de tuits de Vox sobre la inmigración. Cultura, Lenguaje y Representación, 26, 63-82.

Cea D’Ancona, Mª Ángeles. (2004) Métodos de encuesta. Síntesis.

Centro de Estudios Públicos [CEP] (2019). Inmigración en Chile. Sección de obras de política y derecho.

Centro de Estudios Públicos [CEP] (2022). Estudio Nacional de Opinión Pública. Encuesta CEP 88.

Centro Nacional de Estudios Migratorios [CENEM] (2021). Percepción chilena sobre el contexto migratorio actual. Universidad de Talca.

Cinelli, M., De Francisci, G., Galeazzic, A., Quattrociocchi, W. y Starnini, M. (2020). The echo chamber effect on social media. Psychological and cognitive sciences, 118(9). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2023301118

Cirano, R. Espinoza, G. y Jara, F. (2017). Determinantes sociodemográficos de la percepción hacia la inmigración en el Chile de 2017. ICSO N33, UDP.

Correa, S. (2018). El rol del Estado frente a la migración. Un estudio sobre los discursos políticos. Cuadernos de Trabajo Social, 12(1), 85-102.

Dammert, L. y Erlandsen, M. (2020). Migración, miedos y medios en la elección presidencial en Chile 2017. Revista CS, 31, 43-76. https://doi.org/10.18046/recs.i31.3730

Donstrup, M. (2018). Una introducción a los efectos de la comunicación de masas. AdComunica, 255-259. https://doi.org/10.6035/2174-0992.2018.16.16

Doña-Reveco, C. (2022). “Immigrant Invasions to the South American Tiger”: Immigration Representations in chilean newspaper, Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2022.2132570

Douglas, K. M., Mcgarty, C., Bliuc, A. M. y Lala, G. (2005). Understanding Cyberhate: Social competition and social creativity in online white supremacist groups. Social Science Computer Review, 23(1), 68-76. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439304271538

Durán, C. y Thayer, L. (2017). Los migrantes frente a la Ley: Continuidades y rupturas en la legislación migratoria del Estado Chileno (1824-1975). Historia, 7, 429-61.

Erjavec, K. y Kovačič, M. (2012). “You Don't Understand, this is a New War!” Analysis of Hate Speech in News Web Sites' Comments. Mass Communication and Society, 15(6), 899-920. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2011.619679

Etchegaray, N. y Correa, T. (2015). Media Consumption and Immigration: Factors Related to the Perception of Stigmatization among Immigrants. International Journal of Communication, 9. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/3997

Fletcher, R. y Nielsen, R. (2019). Generalized scepticism: how people navigate news on social media. Information, communication & society, 22(12), 1751-1769. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1450887

Gagliardone, I., Gal, D., Alves, T. y Martinez, G. (2015). Countering online hate speech. Unesco Publishing.

Gil de Zúñiga, H., Weeks, B. y Ardèvol-Abreu, A. (2017). Effects of the News-Finds-Me Perception in Communication: Social Media Use Implications for News Seeking and Learning About Politics. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 22(3). https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12185

Gil-de-Zúñiga, H., Correa, T y Valenzuela, S. (2012). Selective Exposure to Cable News and Immigration in the U.S.: The Relationship Between FOX News, CNN, and Attitudes Toward Mexican Immigrants, Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 56(4), 597-615. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2012.732138

González, A. y Pazmiño, M. (2015). Cálculo e interpretación del Alfa de Cronbach para el caso de validación de la consistencia interna de un cuestionario, con dos posibles escalas tipo Likert. Revista Publicando, 2(2), 62-77. https://revistapublicando.org/revista/index.php/crv/article/view/22

Grimes D. R. (2020). Health disinformation & social media: The crucial role of information hygiene in mitigating conspiracy theory and infodemics. EMBO reports, 21(11), e51819.

Hernández, M. y Fernández, M. (2019). Partidos emergentes de la ultraderecha: ¿fake news, fake outsiders? Vox y la web Caso Aislado en las elecciones andaluzas de 2018. Teknokultura, 16(1), 33-53.

Hernández, R., Fernández, C. y Baptista, P. (2010). Metodología de la investigación (5ta.edición). McGraw-Hill-Interamericana Editores, S.A. de C.V

Hossain, A., Kim, M. y Jahan, N. (2019). Can ‘liking’ behavior lead to usage intention on Facebook? Uses and gratification theory perspective. Sustainability, 11(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041166

Humanes, M. (2019). Selective Exposure in a Changing Political and Media Environment. Media and Communication, 7(3), 1-3. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v7i3.2351

Hun, N., Urzúa, A., Henríquez, D. T. y López-Espinoza, A. (2021). Effect of Ethnic Identity on the Relationship Between Acculturation Stress and Abnormal Food Behaviors in Colombian Migrants in Chile. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 1-7.

Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas [INE] y Servicio Nacional de Migraciones [SNM]. (2022). Estimación de personas extranjeras residentes en Chile al 31 de diciembre de 2021. Informe de distribución nacional y regional.

Ivanova, A. y Jocelin-Almendras, J. (2022). Representations of (Im)migrants in Chilean Local Press Headlines: a Case Study of El Austral Temuco. Int. Migration & Integration, 23, 227-242.

Ivanova, A., Jocelin-Almendras, J. y Samaniego, M. (2022). Los inmigrantes en la prensa chilena: lucha por protagonismo y racismo encubierto en un periódico gratuito. Comunicación y Medios, 31(46), 54-67. https://doi.org/10.5354/0719-1529.2022.67412

Krcmar, M. (2017). Uses and gratifications: basic concepts. En: P. Rössler, C. Hoffner, L. van Zoonen, The international encyclopedia of media effects. Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons.

Lawlor, A. y Tolley, E. (2017). Deciding Who’s Legitimate: News Media Framing of Immigrants and Refugees. International Journal of Communication, 11. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/6273/1946

López, E. (2018). El método Delphi en la investigación actual en educación: una revisión teórica y metodológica. Educación XXI, 21(1), 17-40, https://doi.org/10.5944/educXX1.15536

Méndez, R. (2019). Migración datos y perspectivas para un diálogo complejo. En N. Rojas Pedemonte y J. T. Vicuña (Eds). Migración en Chile. Evidencias y mitos de una nueva realidad (pp. 375-391). Derechos Humanos. Ciencias Sociales y Humanas. LOM ediciones.

Mercado, M. y Figueiredo, A. (2023). Racismo y Resistencias en Migrantes Haitianos en Santiago de Chile desde una Perspectiva Interseccional. Psykhe, 32(1). https://doi.org/10.7764/psykhe.2021.28333

Metzger, M., Hartsell, E. y Flanagin, A. (2020). Cognitive Dissonance or Credibility? A Comparison of Two Theoretical Explanations for Selective Exposure to Partisan News. Communication Research, 47(1), 3-28.

Miró, F. (2016). Taxonomía de la comunicación violenta y el discurso del odio en Internet. Revista de Internet, Derecho y Política, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.7238/idp.v0i22.2975

Mixed Migration Centre (2022). Retornando a Venezuela: motivaciones, expectativas e intenciones. https://mixedmigration.org/resource/returning-to-venezuela/

Montes, V. (2019). Deportabilidad y manifestaciones del sufrimiento de los inmigrantes y sus familias. Apuntes, 46(84), 5-35. https://doi.org/10.21678/apuntes.84.1014

Müller, K. y Schwarz, C. (2020). Fanning the Flames of Hate: Social Media and Hate Crime. Journal of the European Economic Association. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvaa045

Murji, K., y Solomos, J. (2005). Introduction: Racialization in theory and practice. In K. Murji y J. Solomos (Eds.), Racialization: Studies in theory and practice (pp. 1-27). Oxford University Press

Navarrete, B. (2017). Percepciones sobre inmigración en Chile: lecciones para una política migratoria. Migraciones Internacionales, 9(1), 179-209.

Navia, P. y Ulriksen, C. (2017). Tuiteo, luego voto. El efecto del consumo de medios de comunicación y uso de redes sociales en la participación electoral en Chile en 2009 y 2013. Cuadernos.info, 40, 71-88

Nesbet, F., Cárcamo, L. y Becker, K. (2021). Analysis of the Informational Treatment of Immigration in the Chilean Press. Anagramas, 20(39), 83-105. https://doi.org/10.22395/angr.v20n39a4

Ohme, J. (2021). Algorithmic social media use and its relationship to attitude reinforcement and issue-specific political participation – The case of the 2015 European immigration movements. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 18(1), 36-54. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2020.180508510.1080/19331681.2020.1805085

Olmo y Romero, J. (2019). Desinformación: concepto y perspectivas. CIBER elcano https://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/analisis/desinformacion-concepto-y-perspectivas/

Organización Internacional para las Migraciones [OIM] (2020). Informe sobre las Migraciones en el mundo 2020. OIM. https://missingmigrants.iom.int/mixed-migration-routes-central-america-incl-mexico

Pérez, J., Corbeaux, M. y Doña-Reveco, C. (2021). Inmigración y derecho al voto una investigación exploratoria en Santiago de Chile. SocArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/h7abn.

Phua, J., Jin, S. y Kim, J. (2017). Uses and gratifications of social networking sites for bridging and bonding social capital. Computers in human behavior, 72, 115-122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.02.041

Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo [PNUD] (2019). Start-Up Fund for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration. Migration Multi-Partner Trust Fund, Terms of Reference. http://mptf.undp.org/factsheet/fund/MIG00

Ramírez-Dueñas, J. M. y Vinuesa-Tejero, M. L. (2020). Exposición selectiva y sus efectos en el comportamiento electoral de los ciudadanos: la influencia del consumo mediático en el voto en las elecciones generales españolas. Palabra Clave, 23(4), e2346. https://doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2020.23.4.6

Ramírez-García, A., González-Molina, A., Gutiérrez-Arenas, M. y Moyano-Pacheco, M. (2022). Interdisciplinariedad de la producción científica sobre el discurso del odio y las redes sociales: Un análisis bibliométrico. Comunicar, 72, 129-140. https://doi.org/10.3916/C72-2022-10

Roessler, P., Lobos, C., Rojas, N. y Rivera, F. (2022). Inclusión relacional de personas migrantes en Chile: hacia un modelo de medición estadístico. Migraciones Internacionales, 13. https://doi.org/10.33679/rmi.v1i1.2465

Rojas, H. (2006). Communication, participation and democracy. Universitas Humanística, 62, 109-142.

Rolle, C., Rojas, N. y Lawrence, T. (2022). Crisis migratoria y xenofobia en redes sociales. https://acortar.link/EV1Iso

Santana, L. (2016). Ciudadanía en la esfera pública híbrida. En A. Arriagada (Ed.), El mundo en mi mano. La revolución de los datos móviles (pp. 104-119). Fundación País Digital.

Schäfer, C. y Schadauer, A. (2019). Online Fake News, Hateful Posts Against Refugees, and a Surge in Xenophobia and Hate Crimes in Austria. En G. Dell’Orto y I. Wetzstein (Eds.), Refugee News, Refugee Politics: Journalism, Public Opinion and Policymaking in Europe. Routledge.

Scherer, H. (2017). Connecting media use to media effects. En: P. Rössler, C. Hoffner, L. van Zoonen, The international encyclopedia of media effects. Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons.

Scherman, A. y Etchegaray, N. (2021). News Frames in the Context of a Substantial Increase in Migration: Differences Between Media Platforms and Immigrants’ Nationality. International Journal of Communication, 15. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/16993

Scherman, A., Arriagada, A. y Valenzuela, S. (2013). La protesta en la era de las redes sociales: El caso chileno. En A. Arriagada y P. Navia (Eds.), Intermedios. Medios de comunicación y democracia en Chile (pp. 179-197). Ediciones Universidad Diego Portales.

Scherman, A., Etchegaray, N., Pavez, I. y Grassau, D. (2022). The Influence of Media Coverage on the Negative Perception of Migrants in Chile. Environ. Res. Public Health, 19(13). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19138219

Scolari, C. (2015). Ecología de medios: entornos, evoluciones e interpretaciones. Gedisa.

Servicio Jesuita a Migrantes [SJM] (2021). Encuesta Voces Migrantes 2021. Ekhos.

Sibrian, D. (2023). Desinformación sobre (in) migración en Chile. En M. Labrador y C. Reyes (Eds.), La comunicación científica como herramienta contra la desinformación en la neoglobalización (p.50-70). Ril Editores.

Soto-Alvarado, S., Garrido-Castillo, J. y Gil-Alonso, F. (2022). Discursos sobre los motivos para migrar a Chile. De la expulsión a la realización profesional. Migraciones Internacionales, 13. https://doi.org/10.33679/rmi.v1i1.2491

Stefoni, C. y Brito, S. (2019). Migraciones y migrantes en los medios de prensa en Chile: la delicada relación entre las políticas de control y los procesos de racialización. Revista Historia Social y de las Mentalidades, 23(2), 1-28. https://doi.org/10.35588/rhsm.v23i2.4099

Strömbäck, J. (2017). News Seekers, News Avoiders, and the Mobilizing Effects of Election Campaigns: Comparing Election Campaigns for the National and the European Parliaments. International Journal of Communication, 11, 237-258. https://doi.org/1932–8036/20170005

Thorson, K., y Wells, C. (2015). Curated flows: A framework for mapping media exposure in the digital age. Communication Theory, 26(3), 309-32.

Tijoux, M. (2016). Racismo en Chile: la piel como marca de la inmigración. Universitaria.

Urbán, M. (2019). La emergencia de Vox. Apuntes para combatir a la extrema derecha española. Sylone/Viento Sur.

Urzúa, A., Cabrera, C., Carvajal, C. y Caqueo-Urízar, A. (2019). The mediating role of self-esteem on the relationship between perceived discrimination and mental health in South American immigrants in Chile. Psychiatry Research, 271, 187-194

Valenzuela-Vergara, E. (2019). Media Representations of Immigration in the Chilean Press: To a Different Narrative of Immigration? Journal of Communication Inquiry, 43(2), 129-151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0196859918799099

Valera-Ordaz, L. (2018). Medios, identidad nacional y exposición selectiva: predictores de preferencias mediáticas de los catalanes. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 164, 135-154. http://dx.doi.org/10.5477/cis/reis.164.135

Van Dijk, T. (2012). The role of the press in the reproduction of racism. In M. Messer, R. Schroeder y R. Wodak (Eds.), Migrations: Interdisciplinary Perspectives (pp. 15-29). Springer.

Viechtbauer, W., Smits, L., Kotz, D., Budé, L., Spigt, M., Serroyen, J. y Crutzen, R. (2015). A simple formula for the calculation of sample size in pilot studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 68, 1375-1379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.04.014

Wojcieszak, M. y Garrett, K. (2018). Social Identity, Selective Exposure, and Affective Polarization: How Priming National Identity Shapes Attitudes Toward Immigrants Via News Selection. Human Communication Research, 44(3), 247-273. https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/hqx010

Zhang, J. S., Tan, C. y Lv, Q. (2019). Intergroup contact in the wild: Characterizing language differences between intergroup and single-group members in NBA-related discussion forums. In A. Lampinen, D. Gergle y D. A. Shamma (Eds.), Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction (pp. 1-35).

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS, FUNDING AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors’ contributions:

Conceptualization: Sibrian, Nairbis. Software: Núñez, Juan Carlos. Validation: Sibrian, Nairbis; Alfaro, Amaranta. Formal analysis: Sibrian, Nairbis; Alfaro, Amaranta. Data curation:Núñez, Juan Carlos. Drafting-Preparation of the original draft: Sibrian, Nairbis. Drafting-Revision and Editing: Alfaro, Amaranta. Visualization: Núñez, Juan Carlos. Supervision: Sibrian, Nairbis. Project management: Sibrian, Nairbis. All authors have read and accepted the published version of the manuscript: Sibrian, Nairbis; Alfaro, Amaranta; Núñez, Juan Carlos.

Funding: This research received funding from the Research and Doctoral Vice-Rectory of the Universidad del Desarrollo, Chile. Internal Contest, Project Folio 23400185.

Acknowledgments: This research is part of the project "Exposure to hate speech in the media and social networks of migrant communities in Chile", Folio 23400185, of the School of Communications of the Universidad del Desarrollo, Chile. The study was supported by the Catholic Migration Institute in Chile (INCAMI), during the field work.

AUTHORS:

Nairbis Sibrian

Universidad del Desarrollo, Chile.

PhD in Sociology from the Universidad Alberto Hurtado, Chile (2019). Master’s in communication and public policy, University of Arts and Social Sciences, Chile (2010) and Bachelor in Social Communication, Universidad de Los Andes, Venezuela (2007).

Professor and researcher at the School of Journalism, Faculty of Communications, Universidad del Desarrollo, Chile.

Índice H: 1

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8008-5080

Scopus ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=57226138158

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=zwYxouYAAAAJ&hl=en&oi=ao

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Nairbis-Sibrian-2

Academia.edu: https://independent.academia.edu/NAIRBISDESIREESIBRIANDIAZ

Amaranta Alfaro

Universidad Alberto Hurtado, Chile.

Professor and researcher at the Department of Journalism of the Universidad Alberto Hurtado (Chile). She is a journalist and holds a degree in Communication Sciences. She was an Erasmus Mundus scholarship holder to study the European Master in Media, Communication and Cultural Studies (CoMundus) at the universities of Roskilde (Denmark) and Kassel (Germany). She is an associate researcher at the Interdisciplinary Center for Public Policy (CIPP) and the Center for Studies in Science, Technology and Society (CECTS), both at the Universidad Alberto Hurtado.

aalfaro@uahurtado.cl

Índice H: 4

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7159-2486

Scopus ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=57219031888

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=TkuKxkUAAAAJ&hl=en

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Amaranta-Alfaro

Academia.edu: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Amaranta-Alfaro

Juan Carlos Núñez

Universidad del Desarrollo, Chile.

Master in Social Psychology Research, Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, Spain. Social Worker from Universidad Finis Terrae, Chile. Professor of Psychology at the Universidad del Desarrollo.

Índice H: 0

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4026-1865