Political emotions and prototypical narratives: TikTok in political campaigns: a case study

Political emotions and prototypical narratives: TikTok in political campaigns: a case study

Emociones políticas y narrativas prototípicas: TikTok en las campañas políticas, estudio de caso

Jaime Andrés Wilches-Tinjacá. Grancolombiano Polytechnic University Institution. Colombia.

jwilches@poligran.edu.co

Hugo Fernando Guerrero-Sierra. Santo Tomás University. Colombia. hugo.guerrero@usantoto.edu.co

César Niño. La Salle University. Colombia.

How to cite this article:

Wilches-Tinjacá, Jaime Andrés; Guerrero-Sierra, Hugo Fernando, & Niño, César (2024). Political emotions and prototypical narratives: TikTok in political campaigns, a case study [Emociones políticas y narrativas prototípicas: TikTok en las campañas políticas: estudio de caso]. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 82, 1-29. https://doi.org/10.4185/rlcs-2024-2234

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The use of TikTok as an electoral campaign strategy was key during Colombia’s last presidential elections. This article intends to analyze how this social network influenced the candidacies of Gustavo Petro and Rodolfo Hernández. Methodology: The authors applied a qualitative approach, using a working corpus of 200 TikTok pieces of content, created by the two candidates from the official announcement of their candidacies until the end of the runoff elections. The authors organized the information with content analysis matrices and data processing in Python, from three conceptual categories in electoral campaigns: a. Intentions: the creation of communicative items by the candidates based on the production possibilities of TikTok and hashtags; b. Strategies: political emotions and prototypical narratives that standardize the performance of campaigns, from the speeches issued in the social network; and c. Tools: users' interest in the electoral contest, taking Google trends reports and content’s engagement levels as a reference. Results and Discussion: a. The predominant pattern describes a political leader personalized through an emotional one-minute story, by means of which he presents himself close to TikTok’s multimedia interaction patterns; b. In both cases, the narrative deal with change-oriented political emotions, through which the candidates represent themselves as heroes, tasked with bringing hope to their voters in the face of crisis and uncertainty scenarios; c. Candidates’ accounts are more popular and interesting than the news related to debate spaces, proposals and government plans. Although both campaigns slightly decreased their content production by the run-offs, Petro kept a stable growth curve and engagement level with users, while Hernández reduced his interaction and impact. Conclusions: The article contributes to the literature on political campaigns with the arrival of TikTok and the increase in the use of social networks and digital platforms as marketing strategies in future electoral scenarios.

Keywords: TikTok, Gustavo Petro; Rodolfo Hernández; Elections; Campaigns; Narratives; Emotions.

RESUMEN

Introducción: las elecciones presidenciales en Colombia estuvieron marcadas por la utilización de TikTok como estrategia de campaña electoral. El objetivo del artículo es analizar el uso de esta red social en las candidaturas de Gustavo Petro y Rodolfo Hernández. Metodología: se utiliza un enfoque cualitativo que toma como corpus de trabajo doscientos contenidos realizados en TikTok por los dos candidatos desde el anuncio oficial de sus postulaciones hasta la finalización de las elecciones en segunda vuelta. La información se organizó con matrices de análisis de contenido y procesamiento de datos en Python, desde tres categorías conceptuales en campañas electorales: a. Intenciones: creación de piezas comunicativas de los candidatos desde las posibilidades de producción de TikTok y las etiquetas (hashtags); b. Estrategias: emociones políticas y narrativas prototípicas que estandarizan los performance de campañas, desde los discursos emitidos en la red social y c. Herramientas: el interés de los usuarios por la contienda electoral, tomando como referencia los reportes de Google trends y los niveles de compromiso con los contenidos (engagement). Resultados y Discusión: a. Predomina la personalización del líder político desde un relato emotivo y corto que no supera un minuto de exposición y orientado a mostrarse cercano a las formas de interacción multimedial de TikTok; b. Los roles narrativos están enfocados en los dos casos con emociones políticas orientadas al cambio y en la que se autorrepresentan como héroes con la misión de llevar esperanza a sus electores ante escenarios de crisis e incertidumbre; c. Las cuentas de los candidatos superan en popularidad e interés a las noticias relacionadas con espacios de debate de propuestas y planes de gobierno. Aunque las dos campañas tuvieron leves descensos de producción de contenidos para la segunda vuelta, Petro mantuvo una curva de crecimiento y nivel de compromiso con los usuarios, mientras Hernández redujo su interacción e impacto. Conclusiones: el artículo aporta en la literatura de campañas políticas con la llegada de TikTok y el incremento en el uso de redes sociales y plataformas digitales como estrategias de mercadeo en futuros escenarios electorales.

Palabras clave: TikTok, Gustavo Petro; Rodolfo Hernández; Elecciones; Campañas; Narrativas; Emociones.

1. INTRODUCTION

Political campaigns experience a recurring paradox. Distrust in state institutions has led to a generalized sense of skepticism about democracy. In this context, citizens reject traditional politics and claim for experienced candidates with a solid public office career (Ekström and Sveningsson, 2019; Meneses and Carpio, 2022). However, in the final stages of electoral contests, the personal lives of candidates generate a morbid atmosphere, as the consistency of their words and actions is also under heavy scrutiny. Campaign strategists understand that strong emotions emerge in those moments, almost always associated with the candidate's ability to communicate the overcoming of a frustrating past and the optimistic conquering of the future.

This battlefield of political emotions has been made larger and wider by social networks. Digital platforms have become a place for viral expression of ordinary citizens’ urgent claims related to health, employment, education, housing and other rights. However, these very claims are used to build certain narratives around the candidates, presenting them as down-to-earth, empathetic people to potential voters (Boulianne, 2015).

These practices date back to the very beginning of electoral campaigns and political marketing, due to the complexity of processing rational arguments in a media sphere, characterized by immediacy and the cancellation of specialized language (Kühne et al. 2011). Thus, electoral campaigns now flow along with the transformation of digital platforms and appeal to the canonization of narratives that impact on voters’ primary feelings, with the promise of leaving the design of public policies that will benefit/affect citizens' interests in the hands of experts and technicians.

In this scenario, each social network has become a singular space for political emotion management and content creation (Lin and Himelboim, 2019). Facebook aims to build ties through communities where people can share their experiences with friends (Sánchez-Vizcaíno, 2019). On Instagram, users share multimedia content publicly or privately (Candale, 2017). Twitter (now called X) is characterized by "spontaneity and immediacy, which can foster a fluid exchange of conversation and political debate" (Campos-Domínguez, 2017, p.789). For its part, TikTok is a versatile platform, as it not only opened spaces for sharing political advertising, but it is also a network for personal and entertainment content. It attracts users thanks to an agile content format that becomes dynamic when transformed, analyzed or being ironic by different kinds of communities (Slater, 2022).

Social networks have expanded and transformed political communication strategies, serving as platforms where time and space barriers seem to fade away. In the context of an electoral campaign, candidates aspire to be as present as possible in social networks. However, social networks have developed differentiating elements in terms of the content they offer. For example, Twitter (X) has become a space for debate, micro blog and a scenario for synthetic expression of ideas. TikTok however, as revealed in the development of this article, provides political campaigns with the opportunity to generate trust bonds and close contact with potential voters, not necessarily through ideas, but in this case, through an invitation into aspects of candidates’ daily lives.

In the case of Colombia’s 2022 presidential campaign, TikTok’s versatile entertainment approach allowed the then candidates, Gustavo Petro and Rodolfo Hernández, to present themselves to voters in an innovative and approachable way. In this context, both candidates produced more content in the form of the entertainment message than in the traditional form of political campaigns. Through the recruitment of influencers and the use of musical trends on TikTok, they tried to generate a sense of proximity with the audience, especially that of the youngest generation.

The authors wrote this article from the tabulation of data and the relationship of the categories of the theoretical framework: political emotions, prototypical narratives and social networks; TikTok in this case. From there, they made a manual content analysis of the records of the 2022 presidential candidates Gustavo Petro and Rodolfo Hernández, taking into account that, unlike other networks, TikTok does not have programming mechanisms to share data.

1.1. TikTok enters the political campaign arena

TikTok peaked during the COVID-19 pandemic. The platform was created in China in 2016 under the name "Douyin" by ByteDance. In 2017 ByteDance acquired Musical.ly, an app that allowed users to create and share short 15-second lip sync videos. In 2018, Douyin incorporated this feature, originating the app in the form we know it today.

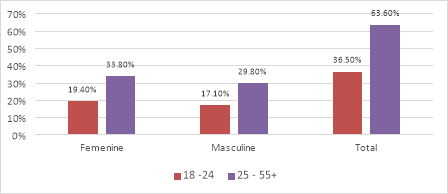

One of the attractions of TikTok is its algorithm. This determines users' tastes and preferences based on their interactions with the app, even if it involves risks of content that generates addictions and mental health problems (González, 2022). However, the platform continues on the rise. By 2021, it was the most downloaded application, with a total of 656 million downloads, 100 million more compared to Instagram (Milenio Digital & DPA, 2022). Thanks to its impact and ability to attract voters, TikTok has become a political communication tool (Castro and Díaz, 2021). This social network is not only used by young people. A total of 63% of TikTok users are over 25 years old (DataReportal, 2022a) as evidenced in Figure 1.

Figure 1. TikTok users by age.

Source: Elaborated by the authors, based on data from DataReportal (2022b).

According to the Digital 2022: Global Overview Report (DataReportal, 2022a), social networks in Colombia are the main source of information for people, with a penetration of 50 million Internet connections (Comisión de Regulación de Comunicaciones, 2022). As a country, Colombia comes fourth in terms of time spent on social networks (DataReportal, 2022a), and sixteenth in terms of TikTok users in the world (approximately 20.11 million users) (Statista, 2023).

This platform promotes viral content and encourages users to create memetic remixes (lip syncing, dance routines, and parodies), so they can express themselves in more enjoyable and personalized ways. TikTok has succeeded not only in creating a collective and self-representation identification of Generation Z (Zeng and Abidin, 2021), even surpassing Google "as the main source of information" (HubSpot and Bradwatch, 2023, p.19). It has also had an impact on adults who, by assimilating its tools, are able to create past-longing content or interact with the latest trends imposed by young people (Vaterlaus and Winter, 2021).

1.2. International cases

Presidential elections have found a new communicational scenario in the marketing of modern politics (Loor-Avila and Baquerizo-Alava, 2021). As Boscán (2021) points out, the politician went from the stage to TikTok. The success of this social network has brought experts to analyze its role and influence within political campaigns. In Latin America, president Nayib Bukele of El Salvador, known as the millennial president, was one of the pioneers in the use of TikTok as a political tool (Figuereo-Benítez et al., 2022).

Ochoa (2022) declares that TikTok has ushered Politics 2.0 in Ecuador, by influencing voting intentions through its content. For example, Guillermo Lasso managed to establish an inclusive speech on TikTok by talking about topics such as family (Barreto and Rivera, 2021).

Something similar occurred in the Peruvian elections (Anastacio, 2022; Cervi et al., 2023) because the pandemic accelerated the trend of exposing the human dimension of politicians by means of these digital tools. In Argentina, Acosta (2022), analyzes the phenomenon through the role of the head of government of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, who found "a new space to present his administration from a more human and humble perspective" (p.198).

López-Fernández (2022) highlights that Madrid-Spain 2021 regional elections campaign and pre-campaign were the first ones in which TikTok became part of the communication strategies. In Italy, Battista (2023), suggests that the elections are articulated in a new era of pop culture mediated by instant videos and agile production thanks to this social network. Gamir and Sánchez (2022) show that the use of TikTok by traditional Spanish political parties such as the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) and the Popular Party (PP) is very low, while it has become a recurrent campaign tool among younger parties such as Podemos, Ciudadanos and Vox (Weimann and Masri, 2020).

Medina et al. (2020), analyze Republican and Democratic political videos posted on TikTok in the U.S. In this case, they identify that supporters of these parties within the platform are young and behave similarly in terms of content production. Experts also talk about the role of TikTok in the politics of countries like Indonesia. Hidayat (2021) analyzed Nahdlatul Ulama's election contest for the general presidency of congress. Candidates did not conduct their political marketing strategies on their own TikTok accounts, but through other account holders in charge of feeding the audience information.

In summary, the international cases reveal this is a growing field of study, since politicians all over the world are very interested in colonizing interactive spaces that bring together citizens/users. In Colombia, experts have already conducted research on recent events related to political activity on TikTok and coming electoral campaigns will surely draw the attention of many more experts onto this phenomenon.

1.3. The context of Colombian presidential elections

Colombia’s 2022 presidential election race resulted in the definition of outsider candidates in the run-offs, and was characterized by a populist speech coming from both wings, right and left (Basset, 2023). Both Rodolfo Hernández and Gustavo Petro appeared as anti-system candidates, who centered their speech in questioning the traditional political elite and the state corruption (Kajsiu, 2022; León, 2022). Colombia was a polarized society, that pushed against/in favor of Iván Duque's government reforms (2018-2022) through digital activism despite COVID-19 confinement measures. In the middle of such turmoil, the anti-system speech was most welcome.

Consequently, the electoral campaign found an online fertile ground to allow the development of a digital strategy, sustained by the flexibility of social networks and the curiosity around two candidates, who seemed closer to the new ways in which voters’ emotions flow. TikTok was the obvious choice since, during COVID-19 confinement, it had become users’ favorite platform (Quiroz, 2020), for its ability, among others, to generate viral content through hashtags (Herrman, 2019), and its appearance during the inter-party consultations between the presidential candidates who decided to submit to a previous scrutiny (Lozano, 2022) and then participated in the presidential elections (Melo and Molano, 2022).

2. OBJECTIVES

This article does not seek to establish a causal link between the victory or defeat of a candidate and the use TikTok, nor whether these campaign strategies are novel in influencing political emotions -to the detriment of the rational/technical argument- involved in scenarios such as the debate. However, it seeks to evidence TikTok was useful in catalyzing (canonical) narrative structures that appeal to feelings of frustration for the past and hope for change. This is a very promising line of research in Latin America, as evidenced by the pioneering work of (Brito and Leiteado, 2022).

The authors intend to establish the strategies that the 2022 Colombian presidential candidates used on TikTok. The working hypothesis suggests the use of the platform was effective in consolidating the messages of the winning candidate (Gustavo Petro), who emulated the strategy initially promoted by the losing candidate (Rodolfo Hernández), who self-proclaimed “King of TikTok” (Valoyes, June 16, 2022). This phenomenon displaced the interest on the debate of government proposals and focused it on emotions around the candidates' private and daily lives.

For the development of the research, the authors propose a theoretical framework around the role of political campaigns and their intentions (appeal to political emotions), strategies (prototypical narratives) and tools (TikTok). These categories are relevant since they involve dimensions that affect the development of electoral processes and articulate the political speech in the era of digitization and viral content on social networks (Boulianne, 2019). In this sense, the study follows the solid line of research on social networks (Zucco et al., 2020) such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and now TikTok as a novel resource in the implementation of political marketing strategies.

The methodology presents the corpus of work in coherence with the three categories of theorization: a. Political emotions: users’ interest in searching for content about the presidential race and campaign proposals (political framework) or content about the candidate’s daily activities (political strategy); b. Prototypical narratives: hashtag-conditioned stories that used to present solutions and change in the face of uncertainty and skepticism scenarios; c. Tiktok: users’ commitment when interacting with the candidates’ content. In the following section the authors present results, according to the above-mentioned categories. They highlight stable and changing periods in the production of content between 2022 presidential elections and run-offs. Finally, the discussions and conclusions point to a renewed line of work in which democracy faces the challenges of political campaigns that will continue taking over social networks and digital platforms to attract voters in order to fulfill personal, partisan or specific interests.

3. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Political campaigns’ communicative strategies reaffirm the consolidation of a scientific field that gathers a wide range of manuals, academic programs and approaches (Subekti et al., 2022), which revolve around the tools a political leader must have to conquer the voters, most of whom do not have time to read government programs. It is at that moment when it is necessary to communicate in effective terms the candidate's connection with the primary emotions of the voters, as well as the need to adapt to the dynamics of social and generational change, theoretical redefinitions and technological transformations.

Due to this variety, the authors have chosen the proposal of Lees-Marshment (2014), since it schematically exposes categories that affect the development of political campaigns from: a. Intentions of strategists and voters' reactions (political emotions); b. Strategies that take the form of discursive mechanisms that seek to spin a narrative (prototypical narratives); and c. Necessary spreading tools to hit the target audience (media or social networks -in the case, TikTok-).

The theoretical approaches to these categories have been deeply conceptualized. For this reason, it is necessary to determine the criteria this article will follow. Categories operate in terms of political emotions, their historical trajectory and their problematization with contemporary political analysis. In terms of prototypical narratives, the authors subscribe to the adaptations of this proposal from the contributions of the semiotics of political speech and its contributions in the structuring of narratives that define role-playing and speech intentions. Finally, the authors consider TikTok not only as a content-spreading tool, but also as a competitive platform, that makes the hypermedia ecosystem more complex.

3.1. Political Emotions

The study of emotions has been a central topic in contemporary political science. A great deal of this interest is related to crises originated in World War II, the dissatisfaction with liberal modernity speech and the imbalances of the economic model. These situations reinforced an individualistic structure characterized by skepticism towards public debate and an ironclad defense of religious tradition, the family and private (and mortgaged in long-term debt) property. Politicians then capitalize on this axiological structure and undertake campaigns that appeal to these seemingly primary feelings, that are ultimately complex and resistant to change, and can even become radical when threatened. Aira (2020) proposes a deeper study of the emotions in politics, and how they can lead to populism and social anxiety (Niño and Vásquez, 2023) when not addressed with pedagogical and pluralistic strategies (Guerrero and Sánchez, 2015), or from social psychology (Gutiérrez-Rubí, 2023).

Hobbes theory of Social Contract had an important role on the way we perceive negative emotions associated with violence, insecurity or fear of death. It was the success of this theory that justified the need for a superior entity called State to act as an impartial moderator of human passions. However, Hobbes theory overlooked the fact that those in charge of offices were human beings, who exercised power under the influence of their interests and emotions. Spinoza proposes a different approach, by placing emotions such as hope as a counterbalance to the violent nature of human beings (Rodríguez and Ricci, 2021).

In view of the inevitability of emotions as a constituent power of human relations, Smith (1979) wrote the Theory of Moral Sentiments, through which the author highlights sympathy and how it can make individuals’ lives more prosperous and succesful.

Through a thorough bibliometric study, Webster and Albertson (2022) conclude that the contemporary world cannot avoid dealing with political emotions, that become more complex thanks to polarizing agents like race, gender and nationality. These differences lead to struggles over meaning and representation, a situation electoral campaigns exploit by designing dividing messages -at the height of the contest-, or moderating and uniting messages -once the voting is over and the candidates claim victory or acknowledge defeat- (Perannagari and Chakrabarti, 2020).

The ability to simplify social passions during the electoral juncture is not only risks the trivialization of the democratic process, but also the naturalization of a deterministic reading of the way emotions are oriented. Political marketing studies have obtained good results in the design of strategies that communicate primary emotions and create empathy between the leader and his/her potential recipients (Wilches et al., 2023).

Words do not matter. It is the government of the least capable (Adams, 1997). According to the work of Vidiella (2013), a rational competitor will be isolated or seen as a stranger. In this regard, and from an Aristotelian perspective, Trueba (2009) reflects on the origins of different emotions and urges, and how they are not necessarily mediated by raising awareness in one’s environment or by its contradictions.

In order to avoid the exploitation of political emotions in electoral contexts, Nussbaum (2014) proposes a pedagogy of emotions to improve public debate and prevent fear, insecurity, distrust and uncertainty about the future. This proposal is grounded in the perspective of García-Villegas (2020), who has analyzed Colombia and its lack of a public sphere. According to the authors, this situation triggers "sad" emotions that can be easily manipulated by political and economic elites.

3.2. Prototypical narratives

Understanding the dynamics of the creation of electoral campaign messages on TikTok requires a multimodal, approach (Cervi et al., 2021) towards prototypical narratives, which according to Ruiz-Collantes et al. (2006), are understood as "narrative frame built on common elements from of a set of narratives that, under certain criteria and at specific levels of their configuration, can be similar and form a homogeneous set" (p. 299).

In this regard, the work of Ruiz-Collantes (2019), is a contribution on how political texts in electoral contexts account for a narrative reflects on the past, the work in the present and provisions for the future. In line with the principles of Greimas and Propp’ semiotics, Ruiz-Collantes (2019) considers that stories within political speeches do not base their influence in accuracy, but rather in the way individuals assimilate and respond to them:

If a story is told using any of the socially standardized narrative schemes, the minds in the audience will relate it to many other similar ones, already true in their memories. Therefore, this story will hold more credibility than any other known and recognizable narrative pattern (p.127)

According to Ruiz-Collantes, the political narrative creates persuasive stories to activate and to raise empathy and solidarity. This is how political speech tells a story carefully structured by a narrative. Benoit (2005) proposes the category of the "storyteller", as a structure that follows canonical narrative principles with temporal lines (setup, confrontation, resolution) and actors (hero, villain, supporters and opponents) (Crespo et al., 2016): the situation should describe a conflict generated by a third party and presented as a need that must be met through a successful resolution.

In the interpretation of Ruiz-Collantes' theory, the aspiring individual or group claims to be able to put and to the disruption in order to obtain legitimacy. Following market logic, now consumers need the product the campaign narrative program is providing. No doubt a provider shall arise to move their emotions in one direction or the other.

3.3. TikTok

As Scolari (2022) points out, communication platforms have transformed everything, from the amount of information available to the way people structure the audiovisual content they consume. The growth of digital media has caused traditional ways of structuring political campaigns to evolve into new strategies that include dialogue with young people, and progressively spreads among adults too (Casero-Ripollés et al. 2016, p.379). The use of social networks is now strategic; online interactions generate an unprecedented volume of information (Espinosa-Oviedo et al., 2016). Data allow both applications and politicians to design the content that the citizens observe, considering emotional or visual messages as factors that directly influence the voter's opinion (González, 2019).

For Benson, Meily and Han (2021), digital platforms in political elections have at least three advantages. First, candidates have more control over campaign messages and they can maximize good publicity and minimize negative by gaining support. Second, candidates have a means to bypass traditional media and send messages directly to target audiences. Third, small political parties with limited budgets or individual candidates without party support can make use of these platforms to gain visibility.

Gil-de-Zúñiga et al. (2010) have even suggested the possibility of a relational and contextual shift based on the use of social networks as tools for political debate. Politicians not only seek to offer citizens online information, but also seek to win their trust and credibility (Corredoira, 2020). Although Twitter (X) is presented as a representation-vindicating platform, its strategy is limited to the exchange of words, with narrow possibilities for images and video. TikTok, on the other hand, has a media structure that rests on audiovisual fascination, supported by a variety of multimedia resources that allow transforming, becoming ironic, trivializing or questioning narratives that go viral in other social networks (Karizat et al., 2021), yet with poor for-or-against feedback. YouTube offers this possibility that revolutionized the ability to pause and fast-forward content on video playback devices, but TikTok advances in auto scroll features (Wang and Guo, 2023), thus taking a decisive step in the simplification of processes and the positioning of the influencer-politician (Cervi, 2023).

According to Conde-del-Río (2021), TikTok’s media structure provides content creators with advantageous interaction resources to move trends and build spontaneous communities (with duets or readapted narratives) TikTok’s media structure makes everyday life more interesting because it gets users involved with adapted versions of stories that connect with their feelings. For example, there is a very interesting cultural phenomenon online around nostalgia for the 80’s and 90’s. These feelings have begun to move younger audiences’ interest towards stories and trends from those decades. These advantages are impossible to ignore within electoral marketing strategies. For this reason, now a candidate starting and leading TikTok trends is the equivalent of the traditional image of a candidate hugging common people in public squares. Both pictures remove the formal politician status and present them on equal ground with the common people, so much so that now a presidential candidate can also be known to create fun content.

This TikTok phenomenon is part of media evolution, similar to when television displaced print and radio in the last century. TikTok might not reign for as long as television did, and could be replaced by another application with exotic interaction possibilities, as proposed by Rathore (2023) when talking about artificial intelligence and metaverse projects in political marketing. According to the study of Lee (2022), this will depend on the ability of algorithms to predict the needs of coming generations and to leverage the characteristics of the digital platform ecosystem: agility, immediacy and concrete messages.

4. METHODOLOGY

The unit of analysis are the publications (videos) made by Gustavo Petro and Rodolfo Hernández in their official TikTok accounts, as well as the information related to the number of videos, comments, hearts and times a message was shared.

The period of analysis covers the publications made from March 13th, 2022, the day Petro was elected as the presidential candidate of the Historical Pact, to June 19th, 2022, the voting day in the run-offs. Since there are two important events in this time period, the authors divided the data between the presidential elections and the run-offs. The former took place from March 13th, 2022 to May 29th, 2022, polling day. The latter took place from May 30th, 2022 to June 19th, 2022, polling day.

Unlike other social networks, and as exposed by the work of Cervi and Marín (2021), TikTok does not have a commercial application programming interface (API), which aims at sharing data about users, their behavior and the interaction of their content. For this reason, the authors collected the data following analysis categories associated with emotions, the narrative semiotics of political speech and TikTok structure. The authors processed the information from a systematized content analysis in Python software.

4.1. Intentions: formats and styles

The authors prepared a content analysis matrix (Chart 1), in which they classified publications into categories: own creation; duets (category that covers content posted on TikTok or videos from other creators in other platforms); and challenge (videos in which the user participates in a viral challenge conditioned by a hashtag of the platform). The authors classified the format of the videos under the following criteria: dialogue only, with music, with effect and with music and effects.

The authors classified the content into three emotional dimensions: personal (private life, family), political (ideas, proposals, criticism) and entertainment (participation in a trend). Since the candidates were participating in an electoral contest, most of their content had a political connotation. That is why the authors made a distinction between publications that have a speech within a political framework -content in which they present government ideas and praise actions or results of the political party or candidate- and publications that focus on a political strategy -stories that seek to exploit weaknesses of the opponent or sympathize with voters through an action that arouses empathy and affection- (Cervi and Marín, 2021).

Chart 1. Content analysis matrix.

|

Category |

|||||||||||

|

Own creation |

|

Duet |

|

Challenge |

|

||||||

|

Content |

|||||||||||

|

Personal |

|

||||||||||

|

Political |

Speech within the political framework |

|

|||||||||

|

Strategic speech |

Political branding (party) |

|

|||||||||

|

Personalization (leader) |

|

||||||||||

|

Acknowledgments |

|

||||||||||

|

Criticism or response to criticism |

|

||||||||||

|

Entertainment |

|

||||||||||

|

Format |

|||||||||||

|

Video (dialogue only) |

|

Video with music |

|

Video with effects |

|

Video with music and effects |

|

||||

Source: Elaborated by the authors, based on Cervi and Marín (2021) and Anastacio (2022).

The proposal is relevant because, on the one hand, is based on methodological designs that respond to the absence of an API for TikTok, and on the other hand, is replicative since it deals with social network structure from a content creator’s perspective.

4.2. Strategies: emotions and prototypical narratives

To design this matrix, the authors turn to the proposal of Ruiz-Collantes (2019), who synthesizes these principles in a narrative program in which political campaigns tell stories and define roles that play this narrative proposal. This position has common elements with the proposal of Crespo et al. (2022), when they classify outrage, fear, change and identity campaigns, that cross the prototypical narrative strategies with the progressive changes in the mood of voters (Chart 2).

Chart 2. Matrix of prototypical narratives and campaign approaches.

|

Disruption approach |

Petro's TikTok. Presidential Elections |

Hernández' TikTok. Presidential Elections |

Petro's TikTok. Run-off Elections |

Hernández' TikTok. Run-off Elections |

|

Outrage: radical questioning of the current government or political system |

|

|

|

|

|

Fear: warning about the potential crisis that the opposition candidate may unleash |

|

|

|

|

|

Change: hope for improvement in a crisis situation |

|

|

|

|

|

Identity: appeal to a group, traditionally excluded from the political, contest, as a crisis-solving agent |

|

|

|

|

|

Narrative Roles |

Petro's TikTok. Presidential Elections |

Hernández' TikTok. Presidential Elections |

Petro's TikTok. Run-off Elections |

Hernández' TikTok. Run-off Elections |

|

Disruption: conflict that breaks normality. Crisis situation and the reason of the mission |

|

|

|

|

|

Disruptive Agent: the cause of the crisis. The villain |

|

|

|

|

|

Disrupted Subject: the one who suffers the consequences of the crisis. The ones in need of saving. |

|

|

|

|

|

Disruption Detector: the one who identifies and reports the crisis. The hero |

|

|

|

|

|

Disruption Disguiser: The one who tries to hide the crisis. The villain |

|

|

|

|

Source: Elaborated by the authors, based on Ruiz-Collantes (2019).

This model is reliable because it is not limited to operate data showing the presence or absence of actors, speeches and strategies. It can also locate content levels with strategic, non-redundant speeches, and how different communicative pieces can guide the homogenization of ideas and values.

4.3. Tools: interest in TikTok and user engagement

In order to learn more about TikTok users’ interests, the authors analyzed each of the engagement indicators (both in presidential elections and run-offs) with Google Trends, able to identify users’ search patterns and establish criteria of popularity taking into account how visible actors and facts are. This tool works through a free combination of keywords users can make, based on criteria set by the interface a. geographical location, b. search time, c. topics, d. website.

The keywords in this case were: “debate presidencial” (presidential debate) -as a central piece in the context of electoral campaigns- (de Liddo et al., 2021), “TikTok de Gustavo Petro” (Gustavo Petro's TikTok) and “TikTok de Rodolfo Hernández” (Rodolfo Hernández's TikTok). As Orduña-Malea (2019) points out, people search for online content related to their "sexual or political inclinations, all of them vastly covered on the news and able to raise audiences' attention and curiosity". This tool allows not only to know the most searched-for term, but also to understand the prediction of future trends within comparative studies (Orduña-Malea, 2019). After identifying the trends, the associated tags are located along with the characteristics of the prototypical narratives.

TikTok videos’ purpose is to lure in, to persuade and, in this case, to influence the perception of potential voters. Therefore, the method uses indicators such as the engagement of each of the candidates' TikTok accounts. This indicator is essential, because it measures the success of the posted content, according to the interaction it creates and its visibility within the endless online universe (García-Marín and Salvat-Martinrey, 2022). Likewise, high levels of engagement indicate that the content creator connects with the audience. For this study, the authors considered the following engagement formula proposed by Ramírez (2021):

Interaction level (Engagement) = [number of Likes + number of Comments + Times Shared X 100) /number of Views].

Although Google Trends cannot be taken as a unique and irrefutable source, since it is also subject to algorithmic conditions and interests, it does constitute a basic tool to explore the trends in the positioning of ideas and values that guide emotions, arouse the interest of electoral strategists and harvest interest to colonize the web in the battle for meaning and representation.

5. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

5.1. Intentions: formats and styles

The processes for the positioning of brands and political messages have also undergone important changes. The use of typical social network languages has turned transcendental issues into compacted information. That discursive reduction complemented by images, symbols and memetic narratives are the combination of new and orthodox ways to move citizens' political emotions in order to occupy a public office. Hashtags are one of TikTok’s most useful tools to increase the visibility of a video. They seek the unite diverse narratives "through a slogan, idea, word or phrase in hashtag format" (Corzo and Chanquía, 2020, p.24), creating a narrative framework with common characteristics. In the presidential campaign of candidates Petro and Hernández, the most popular hashtags were:

● #viral

● #colombia

● #elecciones2022

These tools allow "social networks algorithms to identify video content and show it to the target audience" (Navarro, 2021, p. 31). Hence, the use of tags like #viral, so that large numbers of users watch the video. Likewise, the hashtags #colombia and #elecciones2022 worked as slogan for election-related videos. The candidates created the following hashtags (Chart 3) to maximize the contact of users with their content.

Chart 3. Most popular personal hashtags: Gustavo Petro and Rodolfo Hernández.

|

Gustavo Petro |

No. of times used |

Rodolfo Hernández |

No. of times used |

|

#petro #petropresidente #gustavopetro |

75 31 27 |

#rodolfohernandez #ligaanticorrupcion #rodolfopresidente |

48 37 22 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Each candidate referred to his name mainly as a search term. Likewise, by using #petropresidente or #rodolfopresidente, Petro and Hernández sought to make their political proposal viral. The more either of these two hashtags were shared, the more content would spread, thanks to TikTok's algorithm. It is worth highlighting that Hernandez did not mention any political parties, and Petro remained within the group of organizations aligned with the "Historic Pact". This trend points at a detachment from traditional parties and an inclination towards personalization and individuality of political projects, or the transitory use of legal entities legalized as political parties.

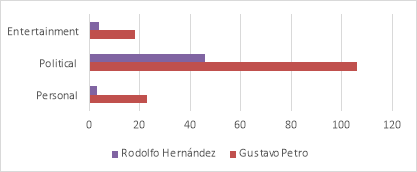

Neither candidate focused his speech only on politics-related content (Figure 2). Videos related to their personal lives, families and privacy were able to mobilize "feelings associated with not-ideological, personal attributes of public figures" (Sarasqueta, 2021, p. 76). In other words, voters develop empathy the person behind the candidate, which undoubtedly works in the latter’s benefit. For example, Petro's campaign dedicated several videos to his family, something that revolves around the idea of family as the cornerstone of the human foundations.

Figure 2. Number of publications by category.

Source: Elaborated by the authors

Candidates’ most popular videos during the campaign period were not thematically related to government proposals. As shown in Figure 1, Hernández's video with the highest number of views shows him imitating an audio that went viral on the platform (relocos papi, relocos). And Petro's presents him eating rice directly from the pot. Whether it is part of a populist message or not, watching a public figure that joins a trend or does everyday activities, attracts viewers’ empathy upon them. It is evident then that appealing to humorous and everyday life content has a more effective impact on the target audience because it generates a pleasant experience (Barta et al., 2023).

On the other hand, both Petro and Hernández resorted to 1-minute videos with slogans that reflected popular social classes’ everyday experience. These messages associated their presidential aspirations with day-by-day activities to show each of them as the closest candidate to voters. This trend reveals how short stories are adapted to draw users’ sympathy onto candidates. There are specific content needs these videos have to meet, they must be shared and, if possible, go viral.

Figure 1. Image of the most popular video of Gustavo Petro and Rodolfo Hernández.

Source: TikTok @gustavopetrooficial and @ingrodolfohernandez.

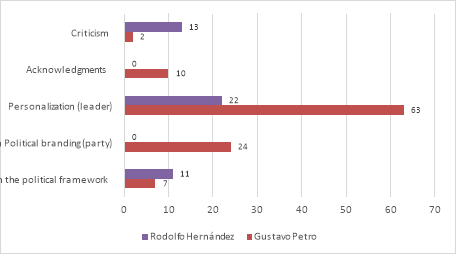

The political content they shared in networks was not only linked to their proposals or did not come in the form of a public meeting speech. Most of the content aimed at promoting the candidates’ image (Figure 3), therefore, there were many videos about their commitment to the people and the country, as well as the results of their political careers.

Figure 3. Number of publications according to political strategy

Source: Elaborated by the authors

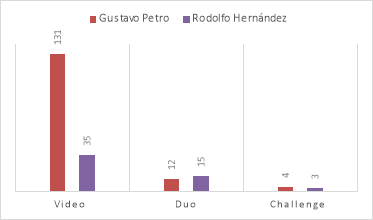

In order to understand the popularity of each account, it is necessary to go over their content (Figure 4), because as García-Marín and Salvat-Martinrey (2022) point out, only the type of content and the subject matter of the videos can predict the level of engagement and its indicators. Regarding this issue, candidates focused on sharing their own content, although Hernandez showed some inclination to use duets. Challenges were not popular among the candidates. Even though candidates did not post any dancing or challenge videos, they did present a fresher and lighter image of themselves.

Figure 4. Number of publications by category

Source: Elaborated by the authors

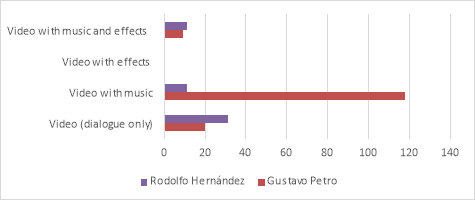

There were differences between the candidates in terms of content format. Regarding the use of music and effects, elements that increase the content’s appeal, the candidates outlined different strategies (Figure 5). On the one hand, "Hernandez’s videos varied from talks and interviews to advertising spots" as stated by Molano and Melo (2022, p.24). In contrast, Petro hardly ever spoke on his videos, and he used viral TikTok music in most of his publications.

Figure 5. Number of publications by format.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Data seem to indicate that rhetorical expositions do not captivate users in this social network, and that it is necessary to appeal to multimedia features. Data also demonstrates that there was an insufficient exploration and use of other possibilities the social network offers, which will constitute a lesson for the development of future political campaigns.

5.2. Strategies: political emotions and prototypical narratives

The analysis of TikTok content shows that both candidates focused on presenting the crisis as an opportunity for change. A hypothesis suggests that Petro could have chosen outrage, but the content analysis shows that he moved onto call for popular mobilization, and appealed to another emotion; excitement in the brink of a new historic moment (Chart 4). Hernández could have appealed to the strategy of fear, but his communication strategy towards ideological sectors that advocate this type of campaign was ambiguous and lost its focus. Another reading of the results suggests that content production focused on identity issues is not relevant. This could imply that the broadcasting of general content aims at avoiding confrontation or the feeling that one of the voting sector has been excluded.

Chart 4. Expression of dislocation in the electoral campaign.

|

|

Petro's TikTok. Presidential Elections |

Hernández' TikTok. Presidential Elections |

Petro's TikTok. Run-off Elections |

Hernández' TikTok. Run-off Elections |

|

Outrage: radical questioning of the current government or political system |

7 |

7 |

2 |

1 |

|

Fear: warning about the potential crisis that the opposition candidate may unleash |

4 |

14 |

2 |

3 |

|

Change: hope for improvement in a crisis situation |

97 |

23 |

18 |

5 |

|

Identity: appeal to a group, traditionally excluded from the political, contest, as a crisis-solving agent |

9 |

0 |

8 |

0 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Chart 5 shows that narratives in each of the roles fit in the structure in the candidates' strategies. The narratives establish correlations in the form of a story, among characters who have predetermined and predictable discursive tones, announcing who their friends and enemies are, what resources are available and the potential obstacles their mission may face. This correlation is expressed with fixed words, actors and contexts arranged in an emotional pattern that, in the case of Colombia, expressed the need for change in the face of the crisis.

Petro made his followers part of his political campaign to secure stronger connections with young sectors and with representatives of social causes (and the support of influencers), while Hernández used TikTok to attack his opponents and defend himself from them. However, Petro changed his strategy creating content for the Colombian population in general (disrupted subject), switching from a campaign focus, that seemed to be on excluded sectors, into the pragmatic and canonical structure of electoral campaigns that resort to zero language and appeal to generalization to attract voters and avoid further divisions.

Chart 5. Prototypical Narratives.

|

Narrative Roles |

Petro's TikTok. Presidential Elections |

Hernández' TikTok. Presidential Elections |

Petro's TikTok. Run-off Elections |

Hernández' TikTok. Run-off Elections |

|

Disruption: conflict that breaks normality. Crisis situation and the reason of the mission |

(14) Family support (8) Electoral fraud, corruption and hate speech. (19) Political career and life (10) Absence, preparation and slander in debates. (6) Vice-presidency and presidency. (17) Proposals for change and development (environmental, animal, children, sports, peace and gender). (18) Tour of Colombia, cultural identity and connection with the population. (4) Support from Latin American parties and governments. (17) Support from influencers, artists, politicians, entrepreneurs, students and kpopers. (4) Publicity and call to action.

|

(5) Other candidates' political scandals and politicking. (3) Touring the country. (8) Achieving the vote and support of the people. (5) Political career without alliances and life. (6) Attendance (non-attendance) to interviews and popularity. (6) Social programs and proposals (work, solving starvation problem, austerity, good deeds, against fracking and having international cultural references). (4) Deficient programs and poor management of other candidates. (4) Support from influencers and family members. (3) Corrupt media and electoral fraud. |

(4) Social and economic inequalities and corruption. (5) Convincing voters and artistic campaigns. (4) Party adhesion and inclusive policies. (12) Touring Colombia, cultural identity and connection with the population. (2) Political career and life. (3) Family support. |

(4) Counter-proposals with Petro (use of networks for the campaign, working hours of the president, persecution of businessmen). (1) Corruption case (Vitalogic) (1) Family support (1) Proposals (University funding) (2) Accomplishing voting and obtaining people's support |

|

Disruptive Agent: the one who causes the crisis. The villain |

(5) Other candidates (Fico, Ingrid Betancur, Ivan Duque). (90) Internal and external opposition. (14) External agents. (1) Media. (3) Male chauvinist opposition. (4) Duque administration, Uribe supporters and Char. |

(2) Politicians (Armando Benedetti and Roy Barreras). (20) Opposition. (3) Traditional parties and coalitions. (6) Media. (13) Other candidates (Fajardo, Fico and Petro). |

(21) Internal and external opposition. (4) Rodolfo Hernández. (4) External agents. (1) Media. |

(3) Petro. (1) Colombian justice. (4) Opposition. (1) Politicians. |

|

Disrupted Subject: the one who suffers the consequences of the crisis. The ones in need of saving. |

(71) Colombian population. (34) Petro and Historical Pact. (10) Women, young people and children. (1) Animals. (1) Kpopers. |

(33) Colombian population. (10) Rodolfo Hernández. (1) Law students and lawyers. |

(22) Colombian population. (5) Petro and Historical Pact. (3) Women and young people. |

(6) Rodolfo Hernández. (1) Muchachada. (1) Businessmen. (1) Colombian population. |

|

Disruption Detector: the one who identifies and reports the crisis. The hero |

(2) Voters. (80) Petro. (16) Petro's family (Verónica, daughters and sons, parents). (2) Gabriel Boric. (2) Francia Márquez. (15) Francia and Petro. |

(40) Rodolfo Hernández. (3) Rodolfo and influencers. (1) Family of Rodolfo Hernández. |

(22) Petro. (1) Petro and Francia. (3) Petro's family. (3) Francia. (1) Voters. |

(8) Rodolfo Hernández. (1) Family of Rodolfo Hernández. |

|

Disruption Disguiser: the one who tries to hide the crisis. The villain |

(5) Uribe supporters and Duque administration. (14) External agents. (90) Internal and external opposition. (5) Politicians and candidates (Fico, Ingrid Betancur). (1) Media. (2) Male chauvinism |

(21) Opposition. (3) Traditional parties and coalitions. (6) Media. (12) Other candidates (Petro, Fico and Fajardo). (2) Politicians (Armando Benedetti and Roy Barreras). |

(22) Internal and external opposition. (4) Rodolfo Hernández. (1) Media. (3) External agents. |

(3) Petro. (1) Colombian justice. (4) Opposition. (1) Politicians. |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

The articulation of the results with the category of political emotions shows that there is a hyper personalization of the candidates (disruption) when the self-representation of the candidate and his life career predominates (disruption detector), almost always represented in struggle scenarios, and in the emotional connection with the family as the nuclear structure to the Colombian idiosyncrasy (disrupted subject), but without taking the risk of singling out any population groups.

It is curious that despite the candidate's hyper-personalization approach, they did not propose to personalize the attributes of their opponent (disruptive agent or disruption disguiser). Petro, on one hand, avoided confrontation with his rival (4 mentions in both cases) and focused on the abstract-ambiguous mention of internal and external opposition (21 and 22 mentions respectively). Hernández, on the other hand, found it hard to detach himself from the outsider figure that criticized all sectors equally (20 and 21 opposition), and he ended up having trouble mentioning the mistakes or inconsistencies of his counterpart (3 mentions in both cases).

TikTok shows candidates in a rather messianic style, with poor or no inclination to debate. Petro was willing to participate, while Hernández was evasive, but both candidates avoided mentioning this topic, the discussion of their ideas or even the option of participating in televised debates. The low rate of mutual direct attacks reaffirms this hypothesis (either as disruptive agent/villains or disruption disguiser), and they chose to generically make other sectors responsible for the crisis (opposition, political class).

5.3. Tools: TikTok interests and user engagements

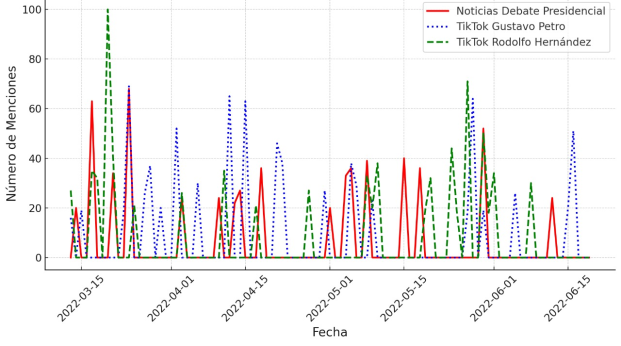

Google Trends results indicate that when crossing news data about "presidential debate", "Gustavo Petro's TikTok", "TikTok", fluctuations appear throughout the campaign, which could be related to specific events or controversies that generated more mentions (Figure 6). Interestingly enough, TikTok has the disadvantage of having only one platform, unlike other portals that could talk about the candidates' discussions, however it ends up being the users’ favorite.

Hernández peaked the beginning of the campaign and at the end of the presidential elections, but then interest in searching for his content faded (778 mentions); Petro kept stable indicators and managed to consolidate attention on his contents in TikTok by the run-offs period (814 mentions). During the presidential debate, candidates raised a rather even amount of interest, without marking overwhelming popularity trends (598 mentions).

Figure 6. Time Series of Mentions and Interactions.

Source: Elaborated by the authors at Phyton, based on data taken from Google Trends.

Note: The number 100 indicates the maximum popularity of a term, while 50 and 0 indicate that a term is half as popular as the maximum value or that there was not enough data for the term, respectively.

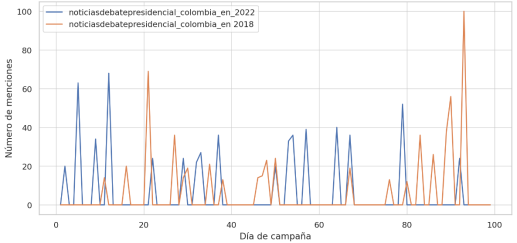

This trend is ratified when comparing the news of "presidential debate" with those of 2018 (Colombia holds elections every four years), and there is an evident reduction of mentions by 2022. One would assume that in a context of media and digital platform evolution, the interest rate should increase. However, data show that citizens do not express interest in electoral contest, to the point that 0 interest terms have visible peaks (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Comparison of Mentions between Presidential Debates in 2018 and 2022.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

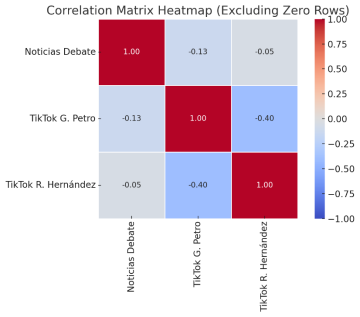

The heatmap also shows the gap between presidential debates as a central practice of the electoral contest and the personalization of the leader in TikTok. There is an evident negative relationship between mentions of the categories (Figure 8). The -0.40 relationship between candidates' TikTok pieces of content reaffirms the interest in self-representation by dropping hints about the personality of the opponent, but not as an invitation to discuss a proposal. Quantitatively, Hernández generated more pieces of news (-0.05), but qualitative data explain this happened because people were curious about an elderly candidate creating content on TikTok.

Figure 8. Heatmap. Relationship between mentions.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Social networks have enhanced the capabilities of political communication strategies. They seem to break down the barriers of time and space. Electoral candidates are everywhere in social networks and their political narratives and messages generate countless amounts of content. Unlike Twitter (X), TikTok helps candidates and their political campaigns generate trust among voters. Through it, politicians invite viewers into aspects of their daily and private lives, which is very effective in creating closeness and empathy feelings (Anastacio-Coello and Montúfar-Calle, 2022). Political speeches now are simpler, more immediate, more compact and are transmitted faster than ever. For this reason, it is easier for them to reach and impact citizens’ everyday life.

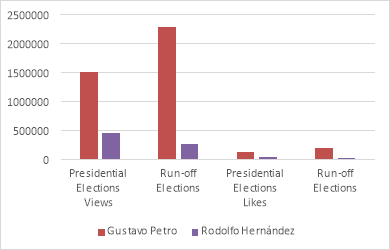

Thanks to its outreach power and entertainment-oriented format (Cervi and Marín, 2021), TikTok allowed both Petro and Hernández to share an alternative and up-to-date speech, by creating entertaining content along with this humble, ordinary, common citizen image (Figure 9), and especially connected to urban music trends like reggaeton.

Figure 9. Presidential candidates' trends on TikTok

Source: TikTok @ingrodolfohernandez and @gustavopetrooficial.

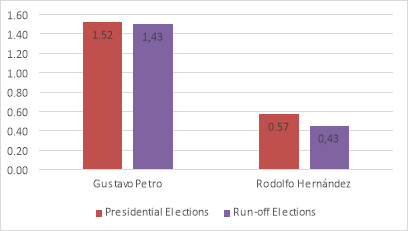

Taking into account the formula of Ramírez (2021), and as established by Navarro (2022): "a total of 3% means that audience engagement is low, while above 3% and 9%, the engagement rate is good. Therefore, 9% and higher, means high audience engagement" (p.23). When reviewing candidates’ engagement rate, the authors identified they achieved a high level of interaction in the presidential elections. However, Petro excelled at increasing his engagement rate, and was even able to strengthen the interaction with his followers by the run-offs (Chart 6).

Chart 6. Engagement in the accounts of Gustavo Petro and Rodolfo Hernández.

|

|

Gustavo Petro |

Rodolfo Hernández |

|

Presidential Elections |

8,64% |

7,07% |

|

Run-off Elections |

8,90% |

5,75% |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

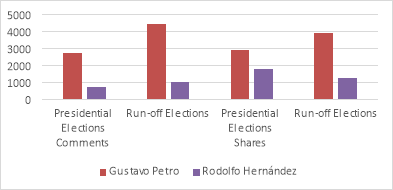

It is important to highlight that election periods do not last the same. Presidential elections lasted 77 days and run-off elections only 20 days, so there is a variation in the numbers when comparing them (Chart 7). Taking this into account, it is evident that both candidates’ content production slightly decreased during run-off election (Figure 10), but surprisingly enough, Hernández abandoned the strategy once he had gone viral as a successful candidate in the social network.

Chart 7. Number of contents produced in TikTok.

|

|

Total amount of videos |

Total amount of videos |

|

Presidential Elections |

117 |

44 |

|

Run-off Elections |

30 |

9 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Figure 10. Average number of videos published per day.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

However, each of Petro’s engagement indicators (number of views, likes, comments and the number of times his videos were shared) experienced an upward trend, unlike Hernández, whose only increasing indicator was the number of comments (Figures 11 and 12). This indicates, that regardless of ideological positions, TikTok worked as instant and effective communication space to obtain votes in the run-offs. It also worked to attract a significant number of swing voters that could have produced many blank ballots -same as in 2018 presidential election. In this sense, Petro’s content production only decreased by 0.9, while Hernández’s decreased by 0.14. This decrease ultimately cast the latter out of debates, a situation he tried to reverse with some late speeches on television (a mass medium in which he appeared apathetic).

Figure 11. Variation in the number of views and likes between presidential and run-off elections.

Source: Elaborated by the authors

Figure 12. Variation between presidential and runoff elections.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Hernández’s type of content helped him boost his campaign all the way through run-off elections (Niño and Galvis, 2022), but he could not keep up and this may have negatively affected his visibility. In addition, he refused to participate in televised debates and chose to stay home, from where he issued distant announcements without the support of a campaign team. On the other hand, Petro took advantage of his popularity on TikTok to show a less formal side of himself and deliver less technical speeches, neither of which he had been able to so far in traditional media. In those speeches, he spoke about his tours around Colombia and all the marginalized and faraway places he visited (Figure 13). The strategy served to present a candidate close to the most vulnerable communities and regions.

Figure 13. Petro and Hernández during run-off elections.

Source: TikTok @ingrodolfohernandez and @gustavopetrooficial.

6. CONCLUSIONS

This article fulfills the objective of analyzing the use of the social network TikTok in the candidacies of Gustavo Petro and Rodolfo Hernández. To this purpose, the authors used analysis strategies to process quantitative and qualitative data, which corroborated their hypothesis: the use of TikTok was key in the victory of Petro's candidacy over Hernández's, as part of strategy that avoided the debate of proposals and focused on appealing to support and empathy emotions of the voters towards the personal attributes of the candidates.

The 2022 Colombian run-off elections were marked by the interest in TikTok as a novel political message-spreading tool. However, both parties had the same goal: to win the presidency and present a disruption narrative: there is an ad hoc crisis situation, that requires a hero to detect the problem and solve it for the common good. Candidates Gustavo Petro and Rodolfo Hernández used TikTok platform to communicate their government ideas in a more attractive, informal and unconventional way.

Thus, the strategies on TikTok appealed to collective emotions, the proximity of the candidate with the public, the similarity between the politician and the common citizen, as well as the empathy with the language and symbols of everyday people. Thus, the authors have corroborated Ruiz-Collantes' thesis, which states that, in order to win votes, political strategists create and tell voters stories. With their own script, heroes and villains, who fight for the control of a (disruptive) situation, these stories usually revolve around apocalyptic realities and unrealistic promises of total change.

Based on the data collected in this research, the authors concluded that TikTok brought candidates Petro and Hernández closer to their voters. By interacting with them through this social network, citizens felt closer to the candidates. In this sense, the classic electoral message with programmatic content was substituted by another that relied on closeness and affability. On their TikTok accounts, candidates invited voters into their daily lives, in order to build trust and empathy.

Evidently, public debate was not the focus of content production. Campaign strategies even ruled out traditional televised presidential debates. As part of a future research agenda, it would be interesting to analyze whether social networks are able to definitively displace traditional media in the dynamics of public debate. TikTok allowed candidates to come closer to all kind of audiences: Internet-era young people and traditional television-debate adults.

In recent times, there has been an important production of literature on political campaigns and the use of social networks, mostly focused on Twitter (X) and Facebook. TikTok has a different structure and there is ongoing research about its impact on electoral strategies for synthesizing proposals, avoiding deep debates and exploiting campaigns’ emotional elements. There are still important challenges ahead related to artificial intelligence applications and their constant evolution in adapting narratives to political interests and manipulating citizens’ preferences.

This article is a contribution in research on the evolution of political communication in electoral campaigns, though the research had limitations. The authors did not make a distinction between urban and rural territories, did not design an instrument to compare search engine algorithms with the interests of TikTok users and did not consider the impact of social network influencers on the positioning of tags. Though limited, the article follows an agenda that identifies political emotions as weapons to fight for meaning. The digital ecosystem is then full of short stories with prototypical narratives and implications in the construction of social representations, the transformation of democracy and the redefinition of public debate.

It is important to determine whether TikTok is part of as a strategy to transform the intention of contents or, it constitutes a tool that, despite its peculiarities, maintains a traditional narrative structure that resorts to political marketing to build empathy for a candidate, present citizens’ distrust in the State, showcase frustrations due to asymmetric economic models and preach hope in a better tomorrow.

Finally, this research is important because it helps understand the communicative transitions of electoral campaigns within the framework of social networks. In this sense, unlike other digital platforms, TikTok is relevant due to the following features: the novelty of an emerging platform; circulation of viral and trendy content; emphasis on younger segments of the population; use of creative and appealing content; compact and fast messages; and open interaction with the audience.

This study sets new research lines related to the communicative message of political campaigns in the context of digital platforms and social networks. In this sense, this article reveals that the use of social networks as a communication tool in political campaigns can serve different purposes. This article has demonstrated that on TikTok, political campaigns can change their traditional format and appeal to a closer and direct relationship between voters and candidates, which builds unprecedented links of empathy between them, based on the feeling of a warmer human contact.

7. REFERENCES

Acosta, M. (2022). La pandemia como oportunidad. El jefe de Gobierno de la ciudad de Buenos Aires en TikTok. Astrolabio: Nueva Época, 29, 181-206. https://doi.org/10.55441/1668.7515.n29.31898

Adams, S. (1997). El principio de Dilbert: un auténtico repaso a jefes, reuniones inútiles, manías de gerente y demás achaques laborales. Garnica.

Anastacio, L. (2022). Análisis de la comunicación política en Twitter y TikTok de los candidatos a la presidencia durante la primera vuelta de las Elecciones Generales de 2021 en Perú [Tesis de Pregrado]. Universidad de Piura de Perú. https://bit.ly/3CyHTex

Anastacio-Coello, L., & Montúfar-Calle, Á. (2022). Policy and Applied Technologies: Analysis of the communicative activities of Peru’s presidential candidates on Twitter and TikTok in the first election round in 2021. En Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies (pp. 259-268). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-6347-6_23

Barreto, K., & Rivera, M. (2021). TikTok como estrategia comunicacional de Guillermo Lasso durante el balotaje electoral 2021 en Ecuador. Tsafiqui, 12(17). https://doi.org/10.29019/tsafiqui.v12i17.959

Barta, S., Belanche, D., Fernández, A., & Flavián, M. (2023). Influencer marketing on TikTok: The effectiveness of humor and followers’ hedonic experience. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 70, 103149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.103149

Basset, Y. (2023). La Segunda Vuelta de 2022: un choque de populismos”. En Gustavo Petro vs. Rodolfo Hernández: ¿Dos populismos encontrados? Universidad del Rosario.

Battista, D. (2023). For better or for worse: politics marries pop culture (TikTok and the 2022 Italian elections). Society Register, 7(1), 117-142. https://doi.org/10.14746/sr.2023.7.1.06

Benoit, L. (2003). Que fait la fiction politique. Reagan le storyteller. Tropismes, 11, 153-165.

Benson, S., Meily, M., & Han, W. (2021). What matters most in the responses to political campaign posts on social media: The candidate, message frame, or message format? Computers in Human Behavior, 121, 106800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106800

Boscán, A. (2022). De la tarima al TikTok: Análisis del impacto de las campañas políticas en la red social de la generación Z en el Ecuador [Tesis de Pregrado]. Universidad Ecotec, Ecuador. https://bit.ly/3AUMuWY

Boulianne, S. (2015). Social Media Use and Participation: A Meta-analysis of Current research. Information, Communication & Society, 18(5), 524-538. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2015.1008542

Boulianne, S. (2019). Revolution in the making? Social media effects across the globe. Information, communication & society, 22(1), 39-54.

Brito, K., & Leitao, P. (2022). Measuring the performances of politicians on social media and the correlation with major Latin American election results. Government Information Quarterly, 39(4), 101745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2022.101745

Campos-Domínguez, E. (2017). Twitter y la comunicación política. El Profesional de la información, 26(5), 785-794. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2017.sep.01

Candale, C. (2017). Las características de las redes sociales y las posibilidades de expresión abiertas por ellas. La comunicación de los jóvenes españoles en Facebook, Twitter e Instagram. Colindancias: Revista de la Red de Hispanistas de Europa Central, 3, 201-218. https://bit.ly/2FDWFow

Casero-Ripollés, A., Feenstra, R. A., & Tormey, S. (2016). Old and new media logics in an electoral campaign. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 21(3), 378-397. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161216645340

Castro-Martínez, A., & Díaz-Morilla, P. (2021). La comunicación política de la derecha radical en redes sociales. de Instagram a TikTok y Gab, la estrategia digital de Vox. Dígitos, 1(7), 67. https://doi.org/10.7203/rd.v1i7.210

Cervi, L. (2023). TikTok Use in Municipal Elections: From Candidate-Majors to Influencer-Politicians. Más Poder Local, 53, 8-29.

Cervi, L., & Marín-Lladó, C. (2021). What are political parties doing on TikTok? The Spanish case. El Profesional de la Información, 30(4). https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2021.jul.03

Cervi, L., Tejedor, S., & Blesa, F. G. (2023). TikTok and Political Communication: The Latest Frontier of Politainment? A Case Study. Media and Communication, 11(2), 203-217.

Cervi, L., Tejedor, S., & Lladó, C. M. (2021). TikTok and the new language of political communication. Cultura, Lenguaje y Representación, 26, 267-287. https://doi.org/10.6035/clr.5817

Comisión de Regulación de Comunicaciones. (2023). En 2022, Colombia alcanzó cerca de 50 millones de conexiones a Internet. https://acortar.link/YWqnLm

Conde-del-Río, M. A. (2021). Estructura mediática de TikTok: estudio de caso de la red social de los más jóvenes. Revista de Ciencias de la Comunicación e Información, 26, 59-77. https://doi.org/10.35742/rcci.2021.26.e126

Corredoira y Alfonso, L. (2020). European Regulatory Responses to Disinformation. Special Attention to Election Campaigns. Derecom, 29, 133-142.

Corzo, L., & Chanquía, M. (2020). La narrativa transmedia del hashtag #mmlpqtp, Participación y protesta social en Twitter. Universidad Nacional de Córdoba.

Crespo-Martínez, I., D'Adamo, O., García, V., & Mora, A. (Coords.) (2016). Diccionario enciclopédico de comunicación política. Centro de Estudios Políticos y Constitucionales.

Crespo-Martínez, I., Garrido-Rubia, A., & Rojo-Martínez, J. M. (2022). El uso de las emociones en la comunicación político-electoral. Revista Española de Ciencia Política, 175-201. https://doi.org/10.21308/recp.58.06

DataReportal (2022a). Digital 2022: Colombia. https://bit.ly/3KFRXVf

DataReportal (2022b). Digital 2022: October Global Statsho. https://bit.ly/3kEzgZ2

de Liddo, A., Souto, N. P., & Plüss, B. (2021). Let’s replay the political debate: Hypervideo technology for visual sensemaking of televised election debates. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 145, 102537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2020.102537

Ekström, M., & Sveningsson, M. (2019). Young people’s experiences of political membership: from political parties to Facebook groups. Information, Communication and Society, 22(2), 155-171. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118x.2017.1358294

Espinosa-Oviedo, J. A., Vargas-Solar, G., Alexandrov, V., & Castel, G. (2016). Comparing electoral campaigns by analysing online data. Procedia Computer Science, 80, 1865-1874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2016.05.480

Figuereo-Benítez, J., Oliveira, J.S., & Mancinas-Chávez, R. (2022). TikTok como herramienta de comunicación política de los presidentes iberoamericanos. Redes sociales y ciudadanía. En I. Aguaded, A. Vizcaíno-Verdú, Á. Hernando-Gómez y M. Bonilla-del-Río (Eds.), Redes sociales y ciudadanía: Ciberculturas para el aprendizaje (pp. 103-112). Grupo Comunicar Ediciones.

Gamir-Ríos, J., & Sánchez-Castillo, S. (2022). The political irruption of short video: Is TikTok a new window for Spanish parties? Communication & Society, 35(2), 37-52. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.35.2.37-52

García-Marín, D., & Salvat-Martinrey, G. (2022). Viralizar la verdad. Factores predictivos del engagement en el contenido verificado en TikTok. El Profesional de la Información, 31(2): e310210. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2022.mar.10

García-Villegas, M. (2020). El país de las emociones tristes. Ariel.

Gil-de-Zúñiga, H., Veenstra, A., Vraga, E., & Shah, D. (2010). Digital democracy: Reimagining pathways to political participation. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 7(1), 36-51. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331680903316742

González, F. (2019). Big data, algoritmos y política: las ciencias sociales en la era de las redes digitales. Cinta de Moebio, 65, 267-280. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0717-554x2019000200267

González, I. (2022). ¿Cómo funciona el algoritmo de TikTok? Thinking for Innovation. https://www.iebschool.com/blog/como-funciona-el-algoritmo-de-tiktok-redes-sociales/

Guerrero, H., & Sánchez, J. (2015). Una Pedagogía de Los Sentimientos. Investigación y Desarrollo, 23(1), 58-90. https://acortar.link/jCiwX4

Gutiérrez-Rubí, A. (2023). Gestionar las emociones políticas. Editorial Gedisa.

Herrman, J. (2019). How TikTok is rewriting the world. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/10/style/what-is-tik-tok.html

Hidayat, R. (2021). Spreading the charm of “feelings of the presidential election” through TikTok ahead of the Nahdlatul Ulama Congress”. International Journal of Social Research, 1(2), 138-147.

HubSpot, & Bradwatch. (2023). Informe sobre las tendencias en redes sociales a escala global. https://shorturl.at/nDVX7

Kajsiu, B. (2022). Colombia elections 2022: left wing populism against right wing anti-politics”. LSE (blog). https://bit.ly/3iZgmLP

Karizat, N., Delmonaco, D., Eslami, M., & Andalibi, N. (2021). Algorithmic folk theories and identity: How TikTok users co-produce knowledge of identity and engage in algorithmic resistance. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 5(2), 1-44. https://doi.org/10.1145/3476046

Kühne, R., Schemer, C., Matthes, J., & Wirth, W. (2011). Affective priming in political campaigns: How campaign-induced emotions prime political opinions. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 23(4), 485-507. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edr004

Lee, J. (2022). A study on the intention and experience of using the metaverse. JAHR, 13(1), 177-192. https://doi.org/10.21860/j.13.1.10

Lees-Marshment, J. (2014). Political marketing: Principles and applications. Routledge.

León, A. (2022). El «rey del TikTok» que quiere ser presidente de Colombia. Nueva Sociedad | Democracia y política en América Latina. https://acortar.link/oSgKiK

Lin, J.-S., & Himelboim, I. (2019). Political brand communities as social network clusters: Winning and trailing candidates in the GOP 2016 primary elections. Journal of Political Marketing, 18(1-2), 119-147. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2018.1478661

Loor-Ávila, B., & Baquerizo-Álava, V. (2022). El efecto TikTok: enfoque teórico-metodológico del manejo de la comunicación política en las generaciones del siglo XXI. Digital Publisher CEIT, 7(2), 27-40. https://doi.org/10.33386/593dp.2022.2-1.939

López-Fernández, V. (2022). Nuevos medios en campaña. El caso de las elecciones autonómicas de Madrid 2021 en TikTok. Universitas, 36, 221-241. https://doi.org/10.17163/uni.n36.2022.09