Revista Latina de Comunicación Social | ISSN 1138-5820 | Año 2024

TikTok como herramienta de comunicación política: el caso de Podemos y el Partido Popular en la ley del “solo sí es sí”

TikTok como herramienta de comunicación política: el caso de Podemos y el Partido Popular en la ley del “solo sí es sí”

Nerea Lozano Hernández. University Jaume I. Spain.

Susana Miquel-Segarra. University Jaume I. Spain.

Daniel Zomeño Jiménez. Universitat Jaume I. España.

![]()

How to cite this article

Lozano Hernández, Nerea; Miquel-Segarra, Susana, & Zomeño Jiménez, Daniel (2024). TikTok as a political communication tool: the case of Podemos and the Spanish Popular Party with regard to the "only yes is yes" law" [TikTok como herramienta de comunicación política: el caso de Podemos y el Partido Popular en la ley del “solo sí es sí”]. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 82, 1-24. https://doi.org/10.4185/rlcs-2024-2262

ABSTRACT

Keywords: Political communication; Political crisis; Law; Social media; Social networks; TikTok; Videos.

RESUMEN

Introducción: TikTok se ha convertido en un importante canal para la difusión de mensajes en formato vídeo dirigidos a las audiencias más jóvenes. El principal objetivo de esta investigación se centra en el análisis de la construcción del mensaje político que tanto Podemos como el Partido Popular han hecho de la plataforma TikTok en torno a una legislación en concreto, como es la del “solo sí es sí”. Metodología: Para alcanzar el objetivo planteado y dar respuesta a las preguntas de investigación formuladas se opta por una metodología cuantitativa y se recurre a la técnica del análisis de contenido sobre una muestra de 80 vídeos publicados por el Partido Popular y Podemos entre el 1 de marzo de 2020 y el 7 de marzo de 2023.Resultados: el uso de TikTok por parte de los dos partidos es muy diferente a nivel del discurso, pero similar en cuanto al empleo de recursos técnicos en la construcción de la imagen, y en ambos casos, con carencias visibles de falta de adecuación a los públicos y a los recursos que ofrece la red. Discusión: Tal y como ocurre con otras plataformas, los partidos no utilizan la potencialidad de la red y sus recursos para alcanzar al público más joven. Conclusiones: Los partidos trasladan el discurso y las estrategias del mundo real al mundo digital, manteniendo los roles de ataque y defensa frente a la ley del “solo sí es sí”.

Palabras clave: Comunicación política; Crisis política; Ley; Medios sociales; Redes Sociales; TikTok; Vídeos.

- INTRODUCTION

Social networks have been gaining importance in recent decades and have become a powerful communication channel. There are many and varied fields that use these social platforms to connect with the public (Gómez and Cantero, 2021). One of those that has gained greater relevance is that of politics because it allows both leaders and users to exchange opinions that end up interfering in the political agenda (Nulty et al., 2016; Martín et al., 2020).

In general, the political participation of citizens is being reflected in all social networks, although in a more relevant way it is happening in TikTok, one of the networks with the highest growth in recent times (IAB, 2022). TikTok is a platform that bases its content on the publication of short, instantaneous videos, and allows its users great versatility when it comes to adding animated backgrounds, sound effects and many other visual filters. The number of downloads of this network in the Google Play Store shows that, in just 6 years since its launch in Spain, it has been downloaded by more than 8.8 million people (Statista, 2023). Likewise, this network is characterized by targeting a young audience, with users between 12-17 years old being the group that uses it the most, only below WhatsApp and Instagram (IAB, 2022).

The increasing visibility that this social network has been gaining among young people and future voters has led political parties and some of their representatives to start sharing content on it (Ariza et al., 2022), especially motivated by the significant change that the Spanish political landscape has undergone.

The bipartisanship installed during the last decades, in which the Popular Party and the PSOE alternated power, ended with the arrival in parliament of Podemos (left-wing populism) and Ciudadanos (center right) in 2015 and Vox (extreme right) in 2019. With the irruption of these parties the ideological arc has suffered a significant fragmentation. This fragmentation has enhanced the ideological polarization of the citizenry (Gidron et al., 2020; García-Escribano et al., 2021), and at the same time has forced the positioning of the parties around issues of interest, among which issues linked to gender and equality stand out (García-Escribano et al., 2021). Social networks, mostly aimed at a young audience, have also reflected this situation, and some research (Durántez-Stolle et al., 2023; Peña-Fernández et al., 2023) affirms that feminism has become a prominent topic, as well as a polarizing one in the political conversation.

In this context, the "only yes is yes" law has been one of the issues that has made its way into the political profiles and has done so with very different positions. The positions between parties in relation to this law on Sexual Freedom are opposed and sometimes a reflection of political polarization. This gap has worsened after the entry into force of the law in October 2022 because it has created a social and political debate due to the effects caused by the reduction of sentences for those convicted of sexual crimes. Podemos defends the legislation and its purpose as it was the Ministry of Equality, during the mandate of Irene Montero, which promoted it. In opposition is the Popular Party which, from the outset, was opposed and critical, which was aggravated by the modification of the sentences declared on this type of crime. This unleashed a campaign against the government, the law and the Minister of Equality, generating enormous political wear and tear (Ortiz and Herrera 2023). This situation led the PSOE, despite being in favor of the law, to present a reform that would go ahead with the support of the Popular Party in April 2023.

In this context, it is considered essential to develop this research that combines the analysis of the TikTok platform in which young people - future and new voters - are on, the "only yes is yes" law that has occupied much of the political plane of the last year and the situation of two parties such as Podemos and the Popular Party, one as part of the government and the other as the main opposition party, with very disparate ideas.

- OBJECTIVES

The main objective of this research (MO) focuses on the analysis of the construction of the political message that both Podemos and the Popular Party have made through the TikTok platform around a specific legislation, such as the "only yes is yes". It also analyzes the differences and/or similarities that may exist in the way of transmitting and communicating the messages of the law by the two parties.

The specific objectives are as follows:

SO1.To analyze and establish the characteristics of the digital content produced for TikTok.

SO1. To identify the protagonists and actors of the videos that star in the messages.

SO3. To contextualize the messages published in the videos, both spatially and temporally.

SO4. To identify the tools and resources used in the edition of the videos.

- THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

- Political audience and technology

Technology is currently a relevant piece in the development of people's daily lives, and it is especially so in a generation that does not remember its world without Internet connection, the so-called Generation Z. This comprises those born from 1995 to 2010 (Díaz-Sarmiento et al., 2017) and it is characterized by having the ability to multitask and use more than one screen simultaneously (Quintana, 2016).

The degree of interest in politics drops as age decreases so Generation Z would be the furthest removed from this field. However, the report published by INJUVE (2021) shows that this trend is changing. An 89% of young people in Spain determine that their information consumption is mostly about politics (Cervi et al., 2021) and 37% say that they are interested in the subject (INJUVE, 2021).

The consumption of political content through social networks or other digital sources has been equated, for the first time, to that on television; 44% was done through television broadcasting and the remaining 46% by browsing social platforms (INJUVE, 2021).

Barack Obama first resorted to social networks to mobilize young people in the 2008 US presidential election (Casero-Ripollés et al., 2017; Lee and Xu, 2018). The format chosen was the live broadcasting of political rallies (Paniagua, 2004). From that moment on, social platforms were seen as a channel in which to disseminate political speeches (López et al., 2016). Over time they have become professionalized and the success could be attributed to two reasons (Kreiss et al., 2018):

- A coherence between the speech issued by the official account of a party and those of the rest of its members.

- The creation of a strategy that addresses the type of audience, the visual message to be transmitted, focused on the leader and allowing interaction with the public.

Social media, in the political field, allow the segmentation of messages according to the interests of the audience. It adds the option of obtaining real-time data on voters' reactions, from which to model messages (Kreiss et al., 2018; Bossetta, 2018).

By using social platforms as a tool for political communication, groups tend to engage in "permanent campaigning" (Gavilanes, 2020). While before appearances were at specific times, now any politician can be present daily in a person's life without the need to search for content. Thus, voters are increasingly refusing the traditional political model that inundates them with proposals or data. They are more moved by knowing their potential rulers and that these firmly defend the causes or symbols for which they fight as individuals (Solá, 2018).

- Political spectacularization

The core of the communicative strategies currently developed by candidates and parties is marked by spectacularization. López and Doménech (2018) define spectacularization as a "narrative and visual style" that is built by appealing to emotions with simple themes and through the personalization of political figures.

On that basis, it is established that spectacularization is an evolution of the dynamics reproduced by infotainment and that, as coined by Thussu (2007), when it comes to politics it is called politainment. Its objectives are to capture the attention of recipients and achieve an impact that leads to action (Carrillo, 2013). In the early 1990s, it is possible to perceive on the television screen how political leaders participated in debates or formats that combined information with entertainment, such as a talk show (Labio, 2008).

Political representatives still choose to attend this type of broadcasting because it is a way to get closer to the electorate that does not watch news programs. The opportunity that these spaces give them to show their more human side is what in part would make the rapprochement between politicians and voters effective (Berrocal et al., 2022).

With the origin of the Internet, this political information had to be adapted and cyberpolitics emerged, which persists today. Cotarelo (2013) defines cyberpolitics as follows:

It is the existence of a new digital agora that is unitary but tremendously differentiated, since the country's government bodies, citizens with their blogs and through their social networks, companies, unions, etc., participate in it on an equal footing (p. 15).

Thus, politainment makes the leap to social networks, which have become one of the main scenarios of political spectacularization (Chadwick, 2013). López and Doménech (2021) identify some predominant characteristics that have been distinguished in this type of spectacular content in social networks:

- Image and video are the two hegemonic formats, since the audiovisual captures greater public attention and causes greater impact (Abejón and Mayoral, 2017). Close-ups focusing on the leader are the most recurrent format (Puentes et al., 2017).

- Lighter messages in which to share concise and simple content to citizens. With a simple and understandable language for the majority, political leaders elaborate arguments with which they extol their merits, solutions to problems and attack the management of the rest of the parties (Meyen et al., 2014).

- Deep personalization because party leaders are at the center of the narrative. More emphasis is placed on highlighting personal qualities than on explaining the proposals and measures of the electoral program (Van-Aelst et al., 2012).

- Public disclosure of private life in order to humanize politicians. In order to connect emotionally with part of the voters who reject the political, they share their personal relationships or pet belongings (Quevedo and Portalés, 2017; Sampietro and Sánchez, 2020). This is possible because they are portrayed in a more spontaneous and authentic way in front of citizens and that the politician in front of a lectern is just another person (Ekman and Widholm, 2017).

The most recurrent dynamic in spectacularization is personalization (Enli and Skogerbø, 2013). The different political groups do this through the self-presentation of their representatives and for this purpose they have three main axes (Van-Aelst et al. 2012): giving the leader greater prominence, making their personality known and deepening their professional skills.

Social networks create an ideal environment to develop personalization because it facilitates showing oneself in a natural and spontaneous way (Borah et al., 2018; Metz et al., 2019). In addition to the impact it can have on networks, going viral, on many occasions these contents gain a place in conventional media platforms.

In Spain, it is common in social networks. In TikTok, as in most social networks, political parties follow the strategy of spectacle governed by the logic of entertainment (Colangelo-Kraan and Soto-Alemán, 2020), where soft and informal content is more relevant (Ramírez and Gómez, 2022). It can be said that political communication dominated by the spectacular and shocking has come to stay in time (López, 2022). However, some authors warn that this aspect of politics may lose effectiveness if it is extended over time because it generates the feeling of frivolizing with issues of concern to society (Valdez et al., 2020; Berrocal et al., 2012).

- TikTok in political communication

TikTok is currently understood as one of the most popular social networks in video creation and dissemination (Gamir and Sánchez, 2022). In TikTok, video is everything because it is the format that can be created and viewed (Gamir and Sánchez, 2022). This is why it is characterized by the possibility of editing and disseminating videos in which brevity, entertainment and simplicity are prioritized (Gómez and Cantero, 2021).

The origin of this network goes back to the technology company in China, ByteDance, which manages Douyin. This is the name that TikTok has in this Asian country, although when the international launch is made in 2017 all countries with the option to download it will do so under the name TikTok (Kaye et al., 2021).

In Spain, TikTok did not arrive until August 2018 and is already one of the fastest growing social networks during its period of activity (Chen et al., 2019). One of the moments of greatest boom was the confinement as a result of COVID-19 in which consuming videos was for many a means of escape as well as entertainment for those who decided to open a profile and start creating (Ballesteros, 2020).

In 2022, this upward trend continues and the Social Network Study published by IAB Spain (2022) indicates that TikTok is the fastest growing network for the third consecutive year. Likewise, it is the platform that has reached the maximum record of visualizations with an increase of 250% compared to 2020. The figures may continue to grow in the coming years because it is increasingly present in the user's mind (IAB, 2022).

In a study conducted by Shutko (2020) points out that the most frequent pieces in this social network are comedy and music. Another by Suárez and García (2021) details that the content that reigns in TikTok is the one in which the protagonists are shown in a natural way. Among all this content, the topic of politics is gaining space and is valued as TikTok is one of the forces of political communication (Guinaudeau et al., 2020; Sánchez, 2021).

For the creation of these audiovisual publications in TikTok, users have four methods at their disposal: 15-second videos, one or three minutes and content developed with a series of images (Gamir and Sánchez, 2022). The first three types can be created from a video previously filmed and saved on the cell phone or recorded on the spot through TikTok. Those recorded directly from the platform itself can add filters, music, effects or change their speed, among other resources. These can also be applied to those videos that are shared from the mobile storage or those made up of photographs to which audio or text can be added. When it is time for publication, videos can be accompanied by descriptive text with space for hashtags, which will help in the search for videos and enable their placement in trends (Gamir and Sánchez, 2022).

Although profiles can be followed on TikTok, the consumption of this network is strongly influenced by the algorithm, which selects the content to be displayed in the first tab as soon as the application known as "For you" is opened (Gamir and Sánchez, 2022). It is in that option where users spend most of their time and very few decide to switch to other options such as "Trends" (Vijay and Gekker, 2021).

- Research on political communication in TikTok

Research on this application is in the initial stage (Zulli and Zulli, 2020) and this same situation is transferred to the political arena (Gamir and Sánchez, 2022; Gómez et al., 2023). Some of the research that has been elaborated are those carried out by Cervi and Marín (2021). Through a study of more than 170 videos of Spanish politics, these authors determine that the parties do not make good use of the platform and use it as a means of promotion.

Another valid study is the one conducted by Gamir and Sánchez (2021). This study analyzes 182 publications of the Popular Party, VOX, Podemos and Ciudadanos with a methodology that focuses on the start of the activity, level of interactions or topics. Thus, they conclude once again that the four profiles examined do not fit the resources offered by the application and have faced the limitation marked by the absence of research on TikTok and politics.

As pointed out in different research (Gamir and Sánchez, 2021; Gómez et al., 2023), the best results in terms of communicative activity on TikTok are found in the most polarized formations (Podemos and VOX), compared to the rest of the political formations that focus on disseminating ideological issues, despite the little interest they arouse among the community of this network.

For his part, López (2022) concentrates his research on the Madrid regional elections of 2021 and the political communication strategy exercised in TikTok by the Popular Party, Más Madrid, VOX, Podemos and Ciudadanos. After the review of 198 videos he expresses that the use of the platform is seen as experimental and hardly innovative.

Feminism and the feminization of discourse in TikTok have been the subject of study in more recent research. Quevedo-Redondo and Gómez-García (2023) analyze Sumar's profile, with Yolanda Díaz as the protagonist of most of the videos, and the results show how anti-polarization rhetoric and storytelling contribute to neutralize the tone of the discourses. Peña-Fernández, Larrondo-Ureta and Morales (2023) analyze polarization in TikTok and Twitter around feminism and gender identity. The results show a differential use between both social networks, where TikTok is shown to be a more dialogic tool that allows discussions and conversations in a more neutral tone.

Moreno and Bernárdez (2023), for their part, analyze the specific case of the hoax about "the sexual contract" that arose as a result of the processing of the "only yes is yes law". The research shows the limitations of verification in an era of post-truth, where discourses are based more on emotions than on verifiable facts.

In order to give continuity to the research focused on TikTok and the political sphere, this research analyzes the use of the social network and the communicative strategies carried out from the profiles of two political parties, with an antagonistic approach to a controversial law such as the "only yes is yes" law, with a strong link to gender and equality issues.

- METHODOLOGY

In order to achieve the stated objective and answer the research questions formulated, a quantitative methodology was chosen and the technique of content analysis was used. Through this technique, it will be possible to review the predominant characteristics or resources in the TikTok videos of the official profiles of the Popular Party and Podemos that are related to the "only yes is yes" law.

- Sample

The selection of the political groups that make up the analysis sample was based on three criteria: the degree of involvement with the law under analysis, parliamentary representation and activity or followers on the TikTok social network.

In this way, Podemos (@ahorapodemos) is recognized as the driving party behind this law as it was born in the core of the Ministry of Equality, during Irene Montero's mandate. In terms of representation, it was the fourth most voted force in the last general elections of 2020, which made it one of the pieces of the coalition government. In TikTok it is the account of a political party at national level with the highest number of followers since its first post in January 2020.

Regarding the Popular Party (@partidopopular), it remains as the main opposition party in the parliamentary hemicycle and was the second most voted force in the previous general elections. At first it opposed the approval of such legislation, but once they saw the effects caused, they presented a modification, which went ahead with the support of the PSOE in March 2023. Meanwhile, in TikTok is one of the most active government accounts and was one of the first formations to open it at the beginning of 2019.

After a study of the chronology of the "only yes is yes" law and in view of the entry of the parties to the platform, the time frame of study is established with two key dates. The starting point is March 1, 2020, the date of approval by the Council of Ministers, and extends to March 7, 2023, being the date on which the PP proposal for the reform of the law goes ahead due to the political and social debate it has caused.

Once the period under study had been identified, an in-depth analysis was made of all the videos published on the accounts of both groups during the period in question. In total, 1250 videos were viewed in full, of which 631 corresponded to Podemos and 619 to the Popular Party. In all of them, the speech reproduced was reviewed while observing the cover or the descriptive text accompanying the publication to check the link with the "only yes is yes" legislation. In addition to these parameters, as a check, videos were also filtered by the hashtag #solosiessi or #leysolosiessi.

After applying these criteria, all those videos in which the name of the law is mentioned or written in a direct way and those in which it was treated less concisely were stored. Thus, the final sample extracted consists of 88 videos, 49 of Podemos and 39 of the Popular Party, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Number of videos contributed by each party to the final sample.

|

|

Popular Party |

Podemos |

|

Total videos disseminated |

619 |

631 |

|

Videos on the "only yes is yes" law |

39 |

49 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

- Procedure

PIn order to carry out the content analysis of the sample, we reviewed the methodologies used in recent studies on video in political communication (Gamir and Sánchez, 2020; Cervi et al., 2021; Castro and Díaz, 2021; López, 2021). Thus, we have chosen to adapt a protocol developed from the one used by López Rabadán and Doménech-Fabregat (2018) and it is completed with categories distinguished in other research (Castro and Díaz, 2021; López, 2022).

Once the selected protocols are combined, a model is obtained (Table 2) that groups the categories and variables to respond to the specific objectives proposed:

Table 2: Content analysis protocol.

|

||

|

Video typology |

1. Political activity 2. Media presence 3. Use of celebrities 4. Participation in social demonstrations 5. Summary of party actions 6. Other |

|

|

Purpose of the video |

1. Explaining the proposal 2. Defending the proposal 3. Contrast of information 4. Criticism of party/proposal 5.Other |

|

|

Tone of the message |

1.Neutral 2. Personal 3. Humorous 4. Informative 5. Emotional 6. Offensive 7. Serious 8. Informal 9. Other |

|

|

||

|

Protagonist |

1. Party leader 2. Party member 3. Politicians from other parties 4. Citizens 5. Journalists 6. Personal relationships 7. Affiliates 8. Other 9. No presence |

|

|

Secondary |

1. Party leader 2. Party member 3. Politicians from other parties 4. Citizens 5. Journalists 6. Personal relationships 7. Affiliates 8. Other 9. No presence |

|

|

Gender |

1. Female 2. Male 3. Non-binary person 4. Both (male/female) 5. Not shown |

|

|

||

|

Environment |

1. Institutional 2. Political Meeting 3. Public 4. Private 5. Media sets 6. Not recognizable 7. Others |

|

|

Periods of publication |

1: March 1, 2020 - June 31, 2020 2: July 1, 2020 - October 31, 2020 3: 1 November 2020- 28 February 2021 4: 1 March 2021 - 31 June 2021 5: 1 July 2021 - 31 October 2021 6: 1 November 2021 - 28 February 2022 7: 1 March 2022 - 31 June 2022 8: 1 July 2022 - 31 October 2022 9: 1 November 2022 - 31 December 2022 10: 1 January 2021- 7 March 2023 |

|

|

||

|

Tools |

Emoticons |

1. Use of flags 2. Use of female sex symbol 3. Other 4. Not shown |

|

Stickers |

1: Party relevant members 2: Use of feminist references 3: Presence of flags 4: Other 5: Not shown |

|

|

Graphics |

1. Video subtitles 2. Introduction of well-known individuals 3. Summary of the subject of the video 4. The name of the law is written 5. Other 6. Not shown |

|

|

Filters |

1. Beauty 2. Gaming 3. Not used |

|

|

Resources |

Mentions |

1. Political parties 2. Party affiliates 3. Other political parties 4. Others 5. Not shown |

|

Hashtags |

1. #feminismo 2.#Solosiessi 3. #leysolosiessi 4. #Igualdad 5. #justicia 6. #españa 7. Other |

|

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on López and Doménech (2018); Castro and Díaz (2021); López (2022).

- RESULTS

- Type of posted videos

In order to respond to the first of the objectives (SO1), the message of the posted videos is analyzed, specifically, the type of video, function and tone used by both parties to construct the political message in TikTok is questioned.

The results indicate that the type of video used in the narrative of the "only yes is yes" law by both parties is mostly of political activity developed inside the Parliament.

Thus, half of the videos use this institutional location to give context and rigor to the messages. The Popular Party prioritizes this resource over Podemos.

On the other hand, with an informative and reinforcing value, it is Podemos who resorts mostly to the use of videos that include a summary of the party's actions. We observe how in this matter, it is not usual to resort to the use of celebrities, and Podemos only does it in two occasions.

Despite the media repercussion, the participation of the parties in the demonstrations is not shown in TikTok either, and there is only one video of each of the parties in which this scenario is presented to contextualize the message.

Regarding the dominant function detected in the videos, as shown in Table 3, it is mostly related to criticism. Of the sample submitted to analysis, 30 of the videos followed this pattern, and it is the Popular Party the one that most opts for this function, which is reflected in 90% of the pieces. Criticism is made both of the party that is part of the government and of the "only yes is yes" law itself.

Table 3: Role of the Popular Party and Podemos video on TikTok about the "yes is yes" law.

|

|

@ahorapodemos |

@partidopopular |

|

|

||||

|

Categories |

Cases |

Question% |

Profile % |

Cases |

Question% |

Profile % |

Total Cases |

Total Question % |

|

1: Explaining the proposal |

9 |

18.37% |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

0.00% |

9 |

10.23% |

|

2: Defending the proposal |

20 |

40.82% |

95.24% |

1 |

2.56% |

4.76% |

21 |

23.86% |

|

3: Contrast of information |

7 |

14.29% |

38.89% |

11 |

28.21% |

61.11% |

18 |

20.45% |

|

4: Criticism of party/proposal |

3 |

6.12% |

10.00% |

27 |

69.23% |

90.00% |

30 |

34.09% |

|

5: Other |

10 |

20.41% |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

0.00% |

10 |

11.36% |

|

|

49 |

100.00% |

55.68% |

39 |

100.00% |

44.32% |

88 |

100.00% |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

The controversial nature of the law causes 21 of the pieces to focus on the defense of the legislative measure and for this purpose they are mainly based on the contrast of information related to it. On the one hand, as promoters of the proposal, 95.2% of the videos advocating the proposal are from Podemos, as well as 100% of those explaining it. Meanwhile, the role of the Popular Party is to contrast data. Thus, we see a mainly informative and explanatory use by Podemos as opposed to a position of presenting and exposing data by the PP to counteract the messages emitted by Podemos.

These results are reinforced in the data analyzing the tone of the messages. It is detected that to a greater extent attack and informative are the tones that have been used most frequently (Table 4). The Popular Party is the one that resorts mainly to attack, while the Podemos group is the one that bets on messages with a markedly informative character. Therefore, a position of confrontation -action/reaction- between both parties is evident, in which Podemos represents action, while the Popular Party is positioned in reaction.

Table 4: Tone of the message of the Popular Party and Podemos on TikTok about the "yes is yes" law.

|

|

@ahorapodemos |

@partidopopular |

|

|

||||

|

Categories |

Cases |

Question% |

Profile % |

Cases |

Question% |

Profile % |

Total Cases |

Total Question % |

|

1: Neutral |

1 |

2.04% |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

0.00% |

1 |

1.14% |

|

2: Personal |

1 |

2.04% |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

0.00% |

1 |

1.14% |

|

3: Humorous |

2 |

4.08% |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

0.00% |

2 |

2.27% |

|

4: Informative |

15 |

30.61% |

75.00% |

5 |

12.82% |

25.00% |

20 |

22.73% |

|

5: Emotional |

5 |

10.20% |

55.56% |

4 |

10.26% |

44.44% |

9 |

10.23% |

|

6: Offensive |

6 |

12.24% |

28.57% |

15 |

38.46% |

71.43% |

21 |

23.86% |

|

7: Serious |

4 |

8.16% |

50.00% |

4 |

10.26% |

50.00% |

8 |

9.09% |

|

8: Informal |

5 |

10.20% |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

0.00% |

5 |

5.68% |

|

9: Other |

10 |

20.41% |

47.62% |

11 |

28.21% |

52.38% |

21 |

23.86% |

|

|

49 |

100.00% |

55.68% |

39 |

100.00% |

44.32% |

88 |

100.00% |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

At the same time, in 23.86% of the recordings, several tones coexist simultaneously. The results show the combination of different tones, for example, humor is combined with an informal tone, attack with seriousness and the same for the informative, which is mostly expressed with a serious tone.

The data show that Podemos is the party that uses the greatest variety of tones in its messages because they are present in all categories, while the Popular Party is present in only half of them. The only videos with a neutral and personal tone are from the purple party, as well as those that allude to humor and informal tones. On the other hand, it is worth noting that in both cases the parties make a very limited and reduced use (between 8.16% and 10.26%) of the emotional tone to connect with the public.

- Who is featured in the video

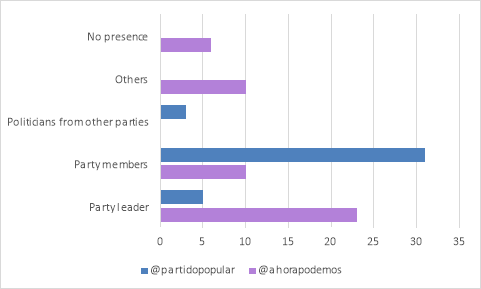

This section shows the results in relation to the protagonists and also to the secondary characters shown in the videos, as well as the predominant gender among the people who appear. The data reflect that the members and leaders of the political party that publishes the video in its profile are the protagonists of the videos. Graph 1 shows that these figures are the central axis of the pieces that make up the sample. It is the Popular Party that follows this trend to a greater extent. Within them, politicians such as the secretary general of the Popular Party, Cuca Gamarra, or the campaign spokesman of the same party, Borja Sémper, are the ones with the greatest presence. Secondly, there is the strategy of concentrating the content on the party leader and making him the center. In this sense, Podemos is the party that personalizes the leader the most.

Figure 1. Video protagonists.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

For Podemos, when talking about a leader, it is unanimously the Minister of Equality Irene Montero, while in the Popular Party, the appearance and references to Alberto Núñez Feijoo, as the maximum leader of the party, are very reduced. It can be observed how Podemos focuses its messages on a single protagonist while the Popular Party diversifies and distributes the presence among several figures of the party.

Affiliates do not appear as protagonists in a very significant way. They do so in only 4.55% of the cases and in all of them they are videos broadcast by Podemos. In turn, the scarce appearance of politicians from other parties as main characters stands out, as well as the very small appearance of citizens as the main interpreters of the videos. The appearance of journalists in the videos is residual. In a very visual way, graph 1 shows that the purple group is the one with the greatest variety of protagonists, while the Popular Party focuses, above all, on making members of the party visible.

As for the secondary characters, it is observed (Table 5) that in 30.84% of the sample no presence of this type of subjects is detected, and therefore it can be seen that the videos are built around the protagonists.

Table 5: Secondary well-known individuals in the videos.

|

|

@ahorapodemos |

@partidopopular |

Total |

|||||

|

Categories |

Cases |

Cases % |

Profile % |

Cases |

Cases % |

Profile % |

Total Cases |

Total Cases % |

|

Party leader |

1 |

1.79% |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

0.00% |

1 |

0.93% |

|

More than 2 secondary subjects |

2 |

3.57% |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

0.00% |

2 |

1.87% |

|

Party members |

9 |

16.07% |

45.00% |

11 |

21.57% |

55.00% |

20 |

18.69% |

|

Politicians from other parties |

10 |

17.86% |

37.04% |

17 |

33.33% |

62.96% |

27 |

25.23% |

|

Citizens |

8 |

14.29% |

72.73% |

3 |

5.88% |

27.27% |

11 |

10.28% |

|

Journalists |

5 |

8.93% |

50.00% |

5 |

9.80% |

50.00% |

10 |

9.35% |

|

Affiliates |

0 |

0.00% |

0.00% |

3 |

5.88% |

100.00% |

3 |

2.80% |

|

No presence |

21 |

37.50% |

63.64% |

12 |

23.53% |

36.36% |

33 |

30.84% |

|

|

56 |

100.00% |

52.34% |

51 |

100.00% |

47.66% |

107 |

100.00% |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

The Popular Party is the one that most shows in its profile representatives of other formations, among which PSOE and Podemos stand out. On a personal level, they focus on the figures of Pedro Sánchez and Irene Montero. The PP introduces and includes in the debate the acronym of the PSOE and the presence of its leader, while Podemos avoids it, focusing all the attention on Podemos and more specifically on the figure of Irene Montero (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Irene Montero stars in @ahorapodemos videos regarding the " only yes is yes" law.

Source: TikTok @ahorapodemos.

Likewise, 18.69% of the videos analyzed include the appearance of members of the same party that has shared it on their profile. In this sense, it is once again the Popular Party that leads this category because in many of the recordings, although it is a subject who speaks, he appears accompanied and supported by other members of the blue group. Again, a support or reinforcement of the messages through different figures of the party is reflected against a predominant use of Irene Montero as central in the messages of Podemos.

While citizens and journalists were not protagonists, they do acquire representation as secondary characters. Podemos is the one that gives more space to citizens, and journalists are equally distributed for both parties. The leader of the party also appears as a secondary character, but only in one case, and it is again Irene Montero.

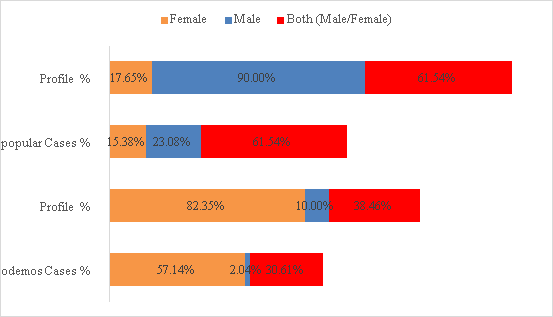

Given the topic addressed by the "only yes is yes" legislation, the gender of the people appearing in the videos was studied, regardless of whether they are in a leading or supporting role. The data indicate that in 44.32% of the videos analyzed there is a combination of figures identified as female and male. As reflected in Figure 3, Podemos is the group that places women at the forefront of the speeches. A result that changes when studying the appearance of only men because the Popular Party achieves a majority with 90% of the cases centered around a male character.

Figure 3. Dominant gender of the well-known indiiduals appearing in the videos.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

- In which scenarios the videos take place

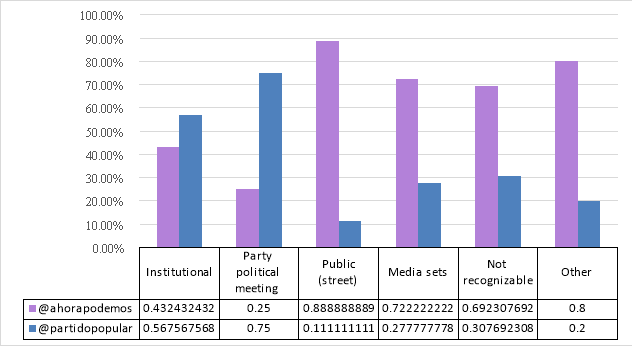

This third part (SO3) focuses on where the videos that make up the sample or what is collected as the space for the action take place. The results reflected in Figure 4 indicate that the common scenario for carrying out the debate on the "only yes is yes" law has been the institutional one.

Figure 4. Scenario in which the action of the videos takes place.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

The parliament and the offices are the space where most of the videos are developed (Figure 5). In this regard, the Popular Party is the one most inclined to this option, while Podemos resorts to the institutional sphere to a lesser extent.

Figure 5: The Parliament is the main stage where the videos take place.

Source: TikTok @partidopopular and @ahorapodemos.

An opposite trend occurs in the pieces understood as cuts on television sets, given that 72.22% of these belong to Podemos. The Popular Party prioritizes the institutional context as opposed to Podemos, which prioritizes the media context. Of the rest of the catalogued spaces, it is worth mentioning the absence of recordings in political rallies of the party. However, a phenomenon based on the difficulty in recognizing the place of filming of the videos is discovered and this is what happens in 13.83% of them.

Also, in six of the videos that make up the sample, the images are reproduced in more than one space. In three of them, all disseminated in the profile of Podemos, the sequence goes from the parliament to a public place such as the street, in two others -one of each party- the institutional is mixed with the media and in the remaining one, of the Popular Party, with a political party demonstration.

On the other hand, according to the results of the research, we observe that the moment of the action chosen by both parties for the creation of the videos disseminated in TikTok is during the development of institutional events held mainly in the parliamentary chamber. The results show that 36.36% of the analyzed pieces respond to this category, the preferred one of the Popular Party. Likewise, participation in the media is another of the moments selected by the parties to talk about this law. In this regard, Podemos is the one who takes the most advantage of this presence and they do it using media such as radio or television, but also in exclusive contents of digital platforms such as RTVE's Gen PlayZ or the podcast Carne Cruda (Raw Meat). The latter formats are mostly identified with a younger audience.

The least frequented spaces are the events organized by the party itself, environments in which the PP publishes 8 of the 12 total videos. There is also the prepared pose, which implies a scarce presence in the total sample. Podemos is the one who mostly chooses to share these prepared moments that denote an amateur character and are used to make videos that are trending on the day of their publication. These moments are presented as a reaction of immediacy to a newsworthy event, susceptible to obtain a greater number of views.

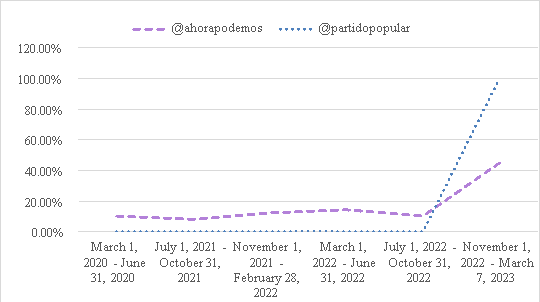

On the other hand, as can be seen in graph 4, the publication and dissemination of videos is agglutinated in two main periods. The maximum peak of activity when it comes to sharing videos on this legislation is from January 1, 2023 to March 7, 2023. In this period 54.55% of the videos in the sample are collected. This period corresponds to the stage in which the first effects of the application of the law regarding the reduction of penalties were being seen and a possible modification by the Popular Party was being debated.

The other period with the highest number of videos is from November 1, 2022 to December 31, 2022. This period corresponds to the days close to the approval of the legislation that comes into force on October 7 of the same year.

As shown in Figure 6, there is a notable difference in publication between the two groups. On the one hand, Podemos mentions the law over a much longer period of time. Its first publication dates back to March 4, 2020, when the draft bill was approved by the Council of Ministers, and its periodicity is maintained throughout the period analyzed. However, the Popular Party concentrates the content and it is not until November 2022 when it begins to include this issue in its profile. Here again it can be seen the action/reaction contraposition that each party undertakes.

Figure 6: Posting date of the videos on TikTok about the "only yes is yes" law.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

- How the videos were created

In accordance with the last of the objectives (SO4), this section deals with how the audiovisual pieces that make up the sample have been developed. It is organized from the technical resources, the use of the tools offered by TikTok for the editing process and finally the tags and mentions to generate traffic to the profile.

The data show a restricted use of emoticons in the videos. In 59.77% of the cases these resources are included, compared to 40.23% of the videos that do not incorporate them. Although the typology of emoticons has not been evaluated, it is noteworthy that the female sex symbol is only used on two occasions, both in videos published by Podemos.

The frequency of one of the most used resources in the edition of videos for TikTok, stickers, was also analyzed. Their use is reduced to a single occasion and Podemos is the party that uses them.

On the contrary, the data reflect how the use of graphics is more frequent.

As can be seen in the data collected in Table 6, both parties use them recurrently to indicate the subject of the video. A second use is that of subtitles, although in this case, their use is quite limited.

Table 6: Use of graphics in TikTok videos regarding the "only yes is yes" law.

|

|

@ahorapodemos |

@partidopopular |

Total Cases |

Total Question % |

||||

|

Categories |

Cases |

Question% |

Profile % |

Cases |

Question% |

Profile % |

||

|

Video subtitles |

6 |

12.24% |

37.50% |

10 |

25.64% |

62.50% |

16 |

18.18% |

|

Introduction of well-known individuals |

1 |

2.04% |

33.33% |

2 |

5.13% |

66.67% |

3 |

3.41% |

|

Summary on the subject of the video |

18 |

36.73% |

42.86% |

24 |

61.54% |

57.14% |

42 |

47.73% |

|

Name of the law |

1 |

2.04% |

100.00% |

|

0.00% |

0.00% |

1 |

1.14% |

|

Other |

2 |

4.08% |

66.67% |

1 |

2.56% |

33.33% |

3 |

3.41% |

|

Not shown |

21 |

42.86% |

91.30% |

2 |

5.13% |

8.70% |

23 |

26.14% |

|

|

49 |

100.00% |

55.68% |

39 |

100.00% |

44.32% |

88 |

100.00% |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

It is worth noting that graphics (Figure 7) are used in 73.86% of the videos of the Popular Party, compared to a more moderate use by Podemos (57.14%). It is worth noting the practically null presence of graphemes that include the name of the "only yes is yes" law. It is only used in one case and it is done by Podemos.

Figure 7: Examples of graphics used in TikTok videos.

Source: TikTok @partidopopular y @ahorapodemos.

The research has also analyzed the textual description that appears in the video caption, and it is in this text that a study of the mentions (@) and tags (#) that have been used has been carried out.

The results show a very limited use of mentions. They have only been used in the videos disseminated by Podemos in 10.41% of the cases. When this resource has been used, it has been to refer to politicians of their own party (Minister of Equality, Irene Montero, the Podemos candidate for mayor of Gijón, Olaya Suárez, the Secretary of State for Equality, Ángela Rodríguez). As an exceptional case, a TikToker is mentioned.

Regarding hashtags, the data are different, 95.97% of the cases include them, even using several in the same publication. Some hashtags have been used by both parties. As shown in Table 7, the most prominent case has been hashtag #españa, which has become the most used, present in 28.86% of the sample. Another of the most used hashtags has been #feminismo, which appears in 19.46% of the total videos, although on this occasion its use is exclusive to Podemos. As an aspect to be remarked is the use of two different hashtags by both parties -#leysolosiessi and #solosiessi - to refer in the same way to the law, causing the content to be less encompassed in the same umbrella. Less relevant is the existence of 6 pieces in which none of the political groups bet on using tags, making it difficult to reach potential voters.

Table 7: Use of hashtags in TikTok videos regarding the "only yes is yes" law.

|

|

@ahorapodemos |

@partidopopular |

Total Cases |

Total Question % |

||||

|

Categoría |

n |

Cases % |

Profile % |

Cases |

Cases % |

Profile % |

||

|

#feminismo |

27 |

29.35% |

93.10% |

2 |

3.51% |

6.90% |

29 |

19.46% |

|

#Solosiessi |

18 |

19.57% |

72.00% |

7 |

12.28% |

28.00% |

25 |

16.78% |

|

#Leysolosiessi |

14 |

15.22% |

77.78% |

4 |

7.02% |

22.22% |

18 |

12.08% |

|

#igualdad |

3 |

3.26% |

75.00% |

1 |

1.75% |

25.00% |

4 |

2.68% |

|

#justicia |

2 |

2.17% |

100.00% |

0 |

0.00% |

0.00% |

2 |

1.34% |

|

#españa |

13 |

14.13% |

30.23% |

30 |

52.63% |

69.77% |

43 |

28.86% |

|

Other |

11 |

11.96% |

50.00% |

11 |

19.30% |

50.00% |

22 |

14.77% |

|

Not included |

4 |

4.35% |

66.67% |

2 |

3.51% |

33.33% |

6 |

4.03% |

|

|

92 |

100.00% |

61.74% |

57 |

100.00% |

38.26% |

149 |

100.00% |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

- DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Political parties include social networks among their usual communication channels and are incorporating in their strategies the new platforms that are emerging to target specific audiences, as is the case of TikTok for younger audiences (Gómez and Cantero, 2021). However, the detailed analysis of the use that the analyzed parties make of TikTok, remains in line with previous research indicating a lack of adequacy of the messages to the logics and frequent and habitual uses that users give to the network (López and Domenech, 2018; Castro and Díaz, 2021; López, 2022, Gamir-Ríos and Sánchez-Castillo, 2022; Gómez de Travesedo-Rojas, et al., 2023).

A lack of adequacy of the narratives to the platform is perceived. It is observed how the informative nature is prioritized over the use of emotional messages, and sometimes, an excessively formal tone is used, more typical of traditional media than of social networks such as TikTok, where entertainment is the main reason (Gómez de Travesedo-Rojas, et al., 2023). Likewise, it is observed how the protagonism falls on very institutional figures far from the young audience with whom they do not feel identified.

Contrary to what López and Doménech (2018) detect in Instagram, also aimed at a young audience, in the TikTok videos that refer to the "only yes is yes" law, the parties do not use an emotional tone to connect with the audience. In this case, use is made of spectacularization based on the criticism of the opposing party and also on the demolition of the "only yes is yes" law itself. The continuous use of these dynamics is contrasted with the scarce explanation of the proposed law by both parties. The content lacks justifications, arguments and explanations, although it is clear that each party has a different and very marked role. While the Popular Party attacks the government and the law, Podemos plays the role of defense. It can be seen how the debate that takes place in the real world is transferred to the digital environment through the videos published and disseminated on TikTok.

The key to the use of TikTok is in the profile of the users, however, the videos shared by the two political formations in their profiles are focused on the daily political activity that is little different from what is seen in the media such as television or other digital platforms. Only in the case of Podemos are there attempts to join trends or viral tags on the TikTok platform, although they do so in a very limited way.

On the other hand, there is also a very limited use of the tools offered by Tiktok for editing and publishing videos (López, 2021; Gamir and Sánchez, 2021). We see how stickers, one of the most used resources in the editing of videos for TikTok, is only used on one occasion, or how subtitling is a one-off feature when it is currently an indispensable condition for the way in which content is consumed in social networks. However, in the specific case of this analysis, the videos related to the "yes is yes" law by Podemos and the Popular Party, an evolution in the use of resources can be seen. As the sample progresses in time, a greater professionalization in the editing of the videos of both parties can be seen. Despite this, they do not reflect a clear and distinctive communicative style. On the other hand, the data allow us to conclude that the figure of the leader does not appear as a protagonist in the narratives constructed by both formations around the "only yes is yes" law. Contrary to the conclusions reached by López and Doménech (2021), it is other secondary characters, such as party members, who assume the leading role in most of the videos. The personalization typical of spectacularization is not found in this case, since there is no mention of personal attributes that help to know the politicians of Podemos or the Popular Party. However, in an outstanding way, the figure of the Minister of Equality, Irene Montero, has become a focus of criticism by the Popular Party (@partidopopular). For some authors, and depending on the results of their research, these criticisms "transcend the management of her Ministry to place her at the center of a power struggle in which political ideology, hate speech and anti-feminism converge" (Durántez-Stolle et al., 2023, p.1).

On the other hand, while López and Doménech (2018) highlighted that Instagram represented a tool that hybridizes political and social (where) spaces. In the case analyzed in TikTok, the opposite occurs, i.e., the focus is placed mainly on institutional places and in the background on the media, leaving aside public places. Some places with great relevance in this law because their origin is linked to feminist demonstrations and that with their absence also make the whole social debate is completely erased.

The moments chosen by the parties to generate their discourse on the law in question, are another of the issues raised by the lack of adequacy of the messages to the audience. In this case, institutional acts and media programs have been the most used environments. This practice clashes with the contributions made by Gómez and Cantero (2021). For these authors, TikTok is an optimal channel for sharing content of events with greater social representation, such as demonstrations or protests. Only Podemos minimally presents spaces of rallies such as that of 8M and the Popular Party remains in events organized by the party itself.

A very relevant issue is the way in which each party incorporates the discourse of the "only yes is yes" law in their TikTok publications. While Podemos bets more on sporadic content, but continued in time since the appearance of the law, the Popular Party does not make reference to it until it does so in a much more concentrated way in the last 6 months. Moments in which the Popular Party has intensified its efforts to attack the purple party and the law. However, and in line with the findings of López and Doménech (2018), just like Instagram, TikTok is a tool that allows following political current affairs and this has been the case with both formations. The content of the videos on the "only yes is yes" law has been interspersed with other topics outside this context.

Along the same lines as concluded above, the use of the platform's own resources such as audio, graphics or mentions has not been integrated in the videos of both formations. Something that is far from what López (2022) explained when in his research, the Popular Party and Podemos bet heavily on the use of stickers or hashtags on Instagram.

With all this and returning to the main objective of the work, we can conclude by saying that the use of TikTok by the Popular Party and Podemos in terms of the "only yes is yes" law is very different at the level of use of the discourse, making their polarization palpable. However, the use is similar in terms of the use of technical resources in the construction of the image, and in both cases, with visible shortcomings in terms of lack of adaptation to the audiences and resources offered by the network (Gamir and Sánchez, 2021; Gómez et al., 2023). Moreover, in the content of the videos of both formations, the most common characteristics of spectacularization are not identified. Many differentiating aspects of this phenomenon have been left out, and one of the few characteristics to which they have referred to this style has been criticism.

Finally, it is worth highlighting the limitations of this study, starting with the limitation of the sample to the context of a specific law, as well as the focus on only two political parties and the manual collection of data. However, with all this, other interesting lines of research remain open, such as the analysis of engagement or the use that political parties and their leaders make of this network to see its evolution and judge its adequacy and effectiveness with young audiences or whether, on the contrary, they limit themselves to transferring the general messages disseminated through other platforms without taking into account the peculiarities and resources offered by the TikTok platform.

Abejón, P. y Mayoral, J. (2017). Persuasión a través de Facebook de los candidatos en las elecciones generales de 2016 en España. El Profesional de la Información, 26(5), 928-936. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2017.sep.14

Ariza, A., March, V. y Torres, S. (2022). Horacio “tiktoker”. Un análisis de los discursos, herramientas, temas y contenidos en la comunicación política del Gobierno porteño en TikTok. Austral Comunicación, 11(1).

Ballesteros, C. (2020). La propagación digital del coronavirus: Midiendo el engagement del entretenimiento en la red social emergente TikTok. Revista Española de Comunicación en Salud, suplemento 1, 171-185. https://doi.org/10.20318/recs.2020.5459

Berrocal, S., Campos, E. y Redondo, G. (2012). El “infoentretenimiento” en Internet. Un análisis del tratamiento político de José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, Mariano Rajoy, Gaspar Llamazares y Rosa Díez en YouTube. Doxa Comunicación, 15, 13-34.

Berrocal, S., Redondo, R. y García, V. (2022). Política pop online: nuevas estrategias y liderazgos para nuevos públicos. Index.comunicación, 12(1), 13-19. https://doi.org/10.33732/ixc/12/01Politi

Borah, P., Fowler, E. y Ridour, T. (2018). Television vs. YouTube: political advertising in the 2012 presidential election. Journal of Information Technology and Politics, 15(3), 230-244. https//:doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2018.1476280

Bossetta, M. (2018). The digital architectures of social media: Comparing political campaigning on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat in the 2016 US election. Journalism & mass communication quarterly, 95(2), 471-496.

Carrillo, N. (2013). El género-tendencia del infoentretenimiento: definición, características y vías de estudio. En C. Ferré-Pavia (Ed.), Infoentretenimiento. El formato imparable de la era del espectáculo. UOC.

Casero-Ripollés, A., López, A. y Marco, S. (2017). What do politicians do on Twitter? Functions and communication strategies in the Spanish electoral campaign of 2016. El Profesional de la Información, 25(5), 795-804. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2017.sep.02

Castro, A. y Díaz, P. (2021). La comunicación política de la derecha radica en redes sociales. De Instagram a TikTok y Gab, la estrategia digital de Vox. Dígitos. Revista de Comunicación Digital, 7, 67-89. https://10.7203/rd.v1i7.210

Cervi, L. y Marín, C. (2021). What are political parties doing on TikTok? The Spanish case. Profesional de la Información, 30(4). https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2021.jul.03

Cervi, L., Tejedor, S. y Marín, C. (2021). TikTok and the new lenguaje of political communication. Cultura, Lenguaje y Representación, 26, 267-287. https://doi.org/10.6035/clr.5817

Chadwick, A. (2013). The hybrid media system: Politics and power. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199759477.001.0001

Chen, Z., He, Q., Mao, Z., Chung, H. M. y Maharjan, S. (2019). A study on the characteristics of Douyin short videos and implications for edge caching. Proceedings of the ACM Turing Celebration Conference, 13, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1145/3321408.3323082

Colangelo-Kraan, P. y Soto-Alemán, L. (2020). Reflexión crítica sobre los vínculos existentes entre YouTube y la televisión. En A. Torres-Toukoumidis y A. De Santis-Piras (Eds.), YouTube y la comunicación del siglo XXI (pp. 69-79). Ediciones CIESPAL.

Cotarelo, R. (Coord.). (2013). Ciberpolítica. Las nuevas formas de acción y comunicación políticas. Tirant Humanidades.

Díaz-Sarmiento, C., López-Lambraño, M. y Roncallo-Lafont, L. (2017). Entendiendo las generaciones: una revisión del concepto, clasificación y características distintivas de los baby boomers, X y millennials. Clío América, 11(22).

Durántez-Stolle, P., Martínez-Sanz, R., Piñeiro-Otero, T. y Gómez-García, S. (2023). Feminism as a polarizing axis of the political conversation on Twitter: the case of #IreneMonteroDimision. El Professional de la Información, 32(6). https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2023.nov.07

Ekman, M. y Widholm, A. (2017). Political communication in an age of visual connectivity: Exploring Instagram practices among Swedish politicians. Northern lights: Film & media studies yearbook, 15(1), 15.32. https://doi.org/10.1386/nl.15.1.15_1

Enli, G. y Skogerbø, E. (2013). Personalized campaigns in party-centred politics: Twitter and Facebook as arenas for political communication. Information, communication and society, 16(5), 757-774. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2013.782330

Gamir, J. y Sánchez, S. (2021). La irrupción política del vídeo corto. ¿Es TikTok una nueva ventana para los partidos españoles? Communication & Society, 35(2), 37-52.

García-Escribano, J., García-Palma, M. B. y Manzanera-Román, S. (2021). La polarización de la ciudadanía ante temas posicionales de la política espanyola. Revista más poder local, 45, 57-73.

Gavilanes, A. (2020). Instagram como plataforma de humanización de líderes de partidos nuevos y tradicionales. Una comparación de la campaña permanente de Pedro Sánchez, Pablo Iglesias, Pablo Casado y Santiago Abascal (enero-marzo 2020) [Trabajo Fin de Máster]. Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

Gidron, N., Adams, J. y Horne, W. (2020). American affective polarization in comparative perspective. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108914123

Gómez de Travesedo Rojas, R., Gil Ramírez, M. y Chamizo Sánchez, R. (2023). Comunicación política en TikTok: Podemos y VOX a través de los vídeos cortos. Ámbitos: Revista Internacional de Comunicación, 60, 71-93.

Gómez, P. y Cantero, J. I. (2021). ¿La política española hacia el mainstream? El fenómeno TikTok. Cosmovisión de la comunicación en redes sociales en la era postdigital, 977-993.

Guinaudeau, B., Vottax, F. y Munger, K. (2020). Fifteen seconds of fame: TikTok and the democratization of mobile video on social media. Unpublished paper. https://osf. io/f7ehq/download

INJUVE. (2021). Informe Juventud en España 2020. INJUVE. www.injuve.es/sites/default/files/adjuntos/2021/03/informe_juventud_espana_2020.pdf

Interactive Advertising Bureau [IAB]. (2022). Estudio de redes sociales 2022. https://iabspain.es/estudio/estudio-de-redes-sociales-2022/

Kaye, D., Chen, X. y Zeng, J. (2021). The co-evolution of two Chinese mobile short video apps: Parallel platformization of Douyin and TikTok. Mobile Media and Communication, 9(2), 229-253. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050157920952120

Kreiss, D., Lawrance, R. y McGregor, S. (2018). In their own words: Political practitioner accounts of candidates, audiences, affordances, genres, and timing in strategic social media use. Political communication, 35(1), 8-31. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2017.1334727

Labio, A. (2008). Periodismo de entretenimiento: la trivialización de la prensa de referencia. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 14, 435-447.

Lee, J. y Xu, W. (2018). The more attacks, the more retweets: Trump’s and Clinton’s agenda setting on Twitter. Public Relation Review, 44(2), 201-213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2017.10.002

López, P. y Doménech, H. (2018). Instagram y la espectacularización de las crisis políticas. Las 5W de la imagen digital en el proceso independentista de Cataluña. El Profesional de la Información, 27(5), 1013-1029. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2018.sep.06

López, P. y Doménech, H. (2021). Nuevas funciones de Instagram en el avance de la “política espectáculo”. Claves profesionales y estrategia visual de Vox en su despegue electoral. El Profesional de la información, 30(2). https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2021.mar.20

López, P., López, A. y Doménech, H. (2016). La imagen política en Twitter. Usos y estrategias de los partidos políticos españoles. Index comunicación, 6(1), 165-195.

López, V. (2022). Nuevos medios en campaña. El caso de las elecciones autonómicas de Madrid 2021 en TikTok. Universitas – XXI, 36, 221-241. https://doi.org/10.17163/uni.n36.2022.09

Martín, J., Soria-Olivas, E., Llosa, Á. y Buendía, V. (2020). La agenda building de los partidos políticos españoles en las redes sociales: Un análisis de Big data. Revista Dígitos, 1(6), 253-274.

Metz, M., Kruikemeier, S. y Lecheler, S. (2019). Personalization of politics on Facebook: Examining the content and effects of professional, emotional and private self-personalization. Information, Communication and Society, 1481-1498. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1581244

Meyen, M., Thieroff, M. y Strenger, S. (2014). Mass Media Logic and the mediatization of politics. Journalism Studies, 15(3), 271-288. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2014.889459

Moreno, I. y Bernárdez, L. (2023). El bulo del ‘contrato sexual’ del Ministerio de Igualdad español en TikTok: un análisis de caso de posverdad antifeminista en redes sociales. ex ӕquo, 48, 33-51. https://doi.org/10.22355/ exaequo.2023.48.04

Nulty, P., Theocharis, Y., Popa, S. A., Parnet, O. y Benoit, K. (2016). Social media and political communication in the 2014 elections to the European Parliament. Electoral studies, 44, 429-444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2016.04.014

Ortiz, A. y Herrera, E. (2023). “Irene Montero: La ofensiva contra la ley del ‘solo sí es sí’ ha sido contra el Gobierno y su presidente” elDiario.es, 20 de abril. https://acortar.link/jvmqIt

Paniagua, F. J. (2004). La nueva comunicación electoral en España. Revista Latina de Comunicación, 59, 96-109.

Puentes, I., Rúas, J. y Dapena, B. (2017). Candidatos en Facebook: del texto a la imagen. Análisis de actividad y atención visual. Revista Dígitos, 1(3), 51-93.

Quevedo, R. y Portalés, M. (2017). Imagen y comunicación política en Instagram. Celebrificación de los candidatos a la presidencia del Gobierno. El Profesional de la Información, 26(5), 916-927. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2017.sep.13

Quevedo-Redondo, R. y Gómez-García, S. (2023). Political communication on TikTok: from the feminisation of discourse to incivility expressed in emoji form. An analysis of the Spanish political platform Sumar and reactions to its strategy. El Profesional de la Información, 32(6), e320611. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2023.nov.11

Quintana, Y. (2016). Generación Z: vuelve la preocupación por la transparencia online. Revista de Estudios de Juventud, 114, 127-142.

Ramírez, M., y Gómez de Travesedo-Rojas, R. (2022). Discursive strategy on UFM on YouTube. Construction of a hate speech. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 80, 259-284.

Sampietro, A. y Sánchez, S. (2020). Building a political image on Instagram: a study of the personal profile of Santiago Abascal (vox) in 2018. Communication & society, 33(1), 169-184. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.33.37241

Sánchez, S. (2021). La construcción del liderazgo político y la identidad escenográfica en TikTok. En Cosmovisión de la comunicación en redes sociales en la era postdigital (pp. 197-210). McGraw-Hill Interamericana de España.

Shutko, A. (2020). User-generated short video content in Social Media: A case study of TikTok. En G. Meiselwitz (Ed.). Lecture Notes in Computer Science, (pp. 108-125). https://acortar.link/sT6kMq

Solá, A. (2018). Encuentra tu causa y moverás el mundo. XIII Cumbre Mundial de Comunicación Política, Lima, Perú.

Suárez, R. y García, A. (2021). Centennials en TikTok: tipología de vídeos. Análisis y comparativa España-Gran Bretaña por género, edad y nacionalidad. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 79, 1-22. https://www.doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2021-1503

Thussu, D. (2007). News as Entertainment. Sage.

Valdez, O., Romero, L. M. y Hernando, A. (2020). La tabloidización y espectacularización mediática: discusión conceptual y aproximaciones empíricas. Comunicación y Hombre, 16, 253-273.

Van-Aelst, P, Sheafer, T. y Stanyer, J. (2012). The personalization of mediated political communication: A review of concepts, operationalizations and key findings. Journalism, 13(2), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884911427802

Vijay, D. y Gekker, A. (2021). Playing politics: How Sabarimala played out on TikTok. American Behavioral Scientist, 65(5), 712-734. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764221989769

Zulli, D. y Zulli D. J. (2020). Extending the Internet meme: Conceptualizing technological mimesis and imitation publics on the TikTok platform. New Media & Society, 24(8). https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820983603

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS, FUNDING AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors’ contributions:

Conceptualization: Lozano Hernández, Nerea and Miquel Segarra, Susana. Software: Lozano Hernández, Nerea. Validación: Miquel Segarra, Susana and Zomeño Jiménez, Dani. Formal analysis: Lozano Hernández, Nerea and Miquel Segarra, Susana. Data Curation: Lozano Hernández, Nerea. Drafting-Preparation of the original draft: Lozano Hernández, Nerea. Drafting-Revision and Editing: Zomeño Jiménez, Dani. Visualization: Zomeño Jiménez, Dani. Supervision: Miquel Segarra, Susana and Zomeño Jiménez, Dani. All authors have read and accepted the published version of the manuscript: Lozano Hernández, Nerea; Miquel Segarra, Susana and Zomeño Jiménez, Dani.

Funding: This research did not receive external funding.

AUTHORS

Nerea Lozano

University Jaume I.

She is currently completing the Official Master's Degree in New Trends and Innovation Processes in Communication at the University Jaume I, specializing in Journalism and Political Communication in the digital era. Graduated from the University Jaume I (UJI) with a degree in Journalism and Advertising and Public Relations. She works as a freelance journalist writing articles for several media and performs Community Manager tasks with the creation and management of content on various social network profiles.

Susana Miquel Segarra

University Jaume I.

She holds a PhD in Communication from the University of Alicante (UA), Spain. Professor in the Department of Communication Sciences at the University Jaume I (UJI). Vice-Dean of the School of Human and Social Sciences (UJI). Member of the research group ENCOM (UJI). Member of the Internal Communication network (EUPRERA). Her main lines of research focus on strategic communication, public relations, internal communication and social networks.

Índice H: 11

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/my-orcid?orcid=0000-0002-0337-7503

Scopus ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=57190666600

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=R-WXwNAAAAAJ&hl=ca

ResearchGate: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/author/record/C-5249-2017

Academia.edu: https://uji.academia.edu/SusanaMiquelSegarra

Daniel Zomeño Jiménez

University Jaume I.

He holds a degree in Fine Arts from the University of Barcelona and a PhD in Communication from the Universitat Jaume I of Castelló. He has worked for more than twenty years as an advertising creative, where he has worked for international agencies such as Ogilvy and BBDO and for independent agencies such as Rosàs or Oriol Villar. Since 2015 he teaches the subject Creativity II and Corporate Video for the Degree in Advertising at the Jaume I University. In postgraduate studies, he teaches Branding and Strategy Towards the New Consumer for the Master's Degree in New Trends and Innovation Processes in Communication. Member of the ENCOM research group. Lines of research: new creative products such as branded content or native advertising and the design of new formats and narratives.

Índice H: 3

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0109-9578

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=7YkfGjwAAAAJ&hl=es

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Daniel-Zomeno