Revista Latina de Comunicación Social. ISSN 1138-5820 / No. 82 1-30.

Fake images, real effects. Deepfakes as manifestations of gender-based political violence

Imágenes falsas, efectos reales. Deepfakes como manifestaciones de la violencia política de género

Almudena Barrientos-Báez. Complutense University of Madrid. Spain.

Teresa Piñeiro Otero. University of A Coruña. Spain.

Denis Porto Renó. State University of São Paulo. Brazil.

This article is the result of the project "AGITATE: gender asymmetries in digital political communication. Practices, power structures and violence in the Spanish tuitesphere" funded by the Instituto de las Mujeres ("Call for public subsidies for feminist, gender and women's research, 2022).

Collaboration with the Complutense Communication Group CONCILIUM (931.791) of the Complutense University of Madrid, "Validación de modelos de comunicación, neurocomunicación, empresa, redes sociales y género" (Validation of communication models, neurocommunication, business, social networks and gender).

How to cite this article

Barrientos-Báez, Almudena; Piñeiro-Otero, Teresa, & Porto Renó, Denis (2024). [Imágenes falsas, efectos reales. Deepfakes como manifestaciones de la violencia política de género] Fake Images, Real Effects: Deepfakes as Manifestations of Gender-based Political Violence. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 82, 1-30. https://doi.org/10.4185/rlcs-2024-2278

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The study addresses the issue of deepfakes and their effect on public perception, highlighting their evolution from ancient practices of visual manipulation to becoming advanced tools for constructing alternative realities, particularly harmful to women. The use of image manipulation as a form of attack or repression leads to considering this practice as part of violence against women in politics. Methodology: This exploratory study delves into the use of manipulated images against female politicians. For this purpose, a multiple methodology was designed: interviews with female politicians, analysis of fake images audited by fact-checkers, and simple searches on adult content platforms. Results: The study reveals the use of fake images as a way to attack and discredit female politicians, predominantly consisting of cheapfakes. Discussion: The limited sophistication in the manipulation of images of female politicians allows for the detection of forgeries by a critical audience. Conclusions: The conclusions underscore the need for media literacy to combat disinformation and confirmation bias. The research emphasizes gender violence in politics, where deepfakes are used to silence and discredit women, thus perpetuating misogyny and the maintenance of existing power structures.

RESUMEN

Introducción: El estudio aborda la problemática de los deepfakes y su efecto en la percepción pública, destacando su evolución desde prácticas antiguas de manipulación visual hasta convertirse en herramientas avanzadas de construcción de realidades alternativas, especialmente lesivas para las mujeres. El uso de la manipulación de imágenes como una forma ataque o represión va a llevar a considerar esta práctica como parte de las violencias contra las mujeres en política. Metodología: Este estudio de carácter exploratorio va a adentrarse en el uso de las imágenes manipuladas contra las políticas. Un objetivo para el que se diseñó una metodología múltiple: entrevistas con mujeres políticas, análisis de imágenes falsas auditadas por verificadores de información y búsqueda simple en plataformas de contenidos para adultos. Resultados: Se pone de manifiesto un empleo de imágenes fake como forma de atacar y desprestigiar a las mujeres política. Dichas imágenes son fundamentalmente cheapfakes. Discusión: La limitada sofisticación en la manipulación de imágenes de mujeres políticas permite la detección de falsificaciones por una audiencia crítica. Conclusiones: Las conclusiones resaltan la necesidad de educación mediática para combatir la desinformación y el sesgo de confirmación. La investigación enfatiza la violencia de género en la política, donde los deepfakes se utilizan para silenciar y desacreditar a las mujeres, perpetuando así la misoginia y el mantenimiento de estructuras de poder existentes.

Palabras clave: deepfake; manipulación de imágenes; misoginia; política; desinformación; pornografía; violencia contra las mujeres en política.

1. INTRODUCTION

The A-Team (A-Team, Universal Television) theme is played. With the famous header of the series, which is part of the imaginary of a generation, the protagonists are presented, which - thanks to a Github user (Iperov) - shows the faces of the main candidates for the presidency of the Government of Spain in the 2019 elections. "Team E- from Spain" is a humorous deepfake from the YouTube channel Face to fake. Among the videos of this channel, there are several productions that take as a basis famous sequences -audiovisual memes (Dawkins, 2006)- for political satire. Thus, a rudimentary deepfake places former Spanish President Mariano Rajoy as the protagonist of Pulp Fiction (Tarantino, 1994), or Vladimir Putin and Volodymir Zelenski as Xerxes and Leonidas in 300 (Snyder, 2007) through the magic of applications such as DeepFaceLab or SberSwap.

But these are not the only examples, the results of the general elections of July 2023 inspired a deepfake with the famous sequence of the bunker in The Sinking (Hirschbiegel, 2004), in which Hitler and his clique integrate the facial faces of politicians of the extreme right wing formation VOX, as well as personalities from the field of communication, with expressions of great realism.

The unrealism of the context, the audiovisual sequence and the comicality of the alleged speech of Santiago Abascal (VOX presidential candidate) aka Hitler, warn the potential audience of the elaborate nature of this speech. However, this is not always the case.

Figure 1: Stills from the recreation of "El hundimiento” (The Sinking) by David Ruiz.

In 2018 filmmaker Jordan Peele and BuzzFeed created a deepfake of Barak Obama, using FaceAPP, in which he called President Trump stupid (President Trump is a total and complete dipshit). The realism of this video, which on the day it was posted reached 100K views on YouTube (Patrini et al., 2018), allowed it to be recorded as truthful evidencing how deepfakes could be used to sow disinformation (Silverman, 2018) Although this particular case was designed as a public warning, it highlighted the vulnerability of society to deepfake technology.

More recently, via WhatsApp, a video of environmental activist Greta Thumberg dancing naked was circulated as a new tactic in her crusade to raise awareness of the threat of global warming. Artificial intelligence had made it possible to replace her face with that of a porn actress, generating a highly realistic video that infringed on the activist's privacy and dignity, as well as mocking her ideas.

Thumberg has not been the only victim of this practice, which uses artificial intelligence tools - in many cases accessible from the mobile app store itself - to generate false images of nudity or pornography. Deepfakes was precisely the nickname of the Reddit user who undressed actresses and singers such as Gal Gadot, Emma Watson, Katy Perry, Taylor Swift and Scarlett Johansson (Cerdán and Padilla, 2019).

At the same time as the first pornographic deepfakes were published, artificial intelligence-based facial transformation applications such as FaceApp appeared, which, based on neural networks, modified the age, expression or gender of a face. They would soon be followed by face replacement applications such as FakeApp or DeepfakeApp, which democratized deepfake production. Beyond the fact that the code base for deepfake projects is open and accessible in spaces such as GitHub (Newton and Stanfill, 2020), the irruption of these applications has allowed the creation of manipulated pieces to users lacking technical expertise.

At the time of writing this text, a group of teenagers between 11 and 17 years of age in Almendralejo (Extremadura, Spain), discovered that they were the protagonists of fake nudes, created by their peers with a deepfake APP, which were circulated mobile to mobile.

While certain online platforms such as the colossus of adult content, PornHub, or Reddit itself have banned or applied significant limitations to these synthetic contents, the deepfake community is still active in unmoderated spaces such as GitHub (Newton and Stanfill, 2020) and dozens of tools for its creation circulate freely on the Net (Angler, 2021), spreading the invasion of privacy and sexual exploitation online (Beamonte, 2018).

In this sense deepfakes should be understood as part of or gendertrolling, a term with which Mantilla (2013) refers to a specific trolling, targeting women. Beyond the mockery or aggressive laughter against a more or less fortuitous victim on the Net, more or less extended in time depending on the reaction of the victim, gender trolling usually has in common its misogynist character, the participation of a high number of users -usually orchestrated-, its extension in time and its special harmfulness. Gender trolling includes various manifestations ranging from hypersexualized representations or macho memes to intimidation, harassment, death threats or rape, which involve the projection of existing violence in the offline world (Piñeiro-Otero et al., 2023).

Newton and Stanfill (2020) highlight toxic geek masculinity as inherent to the deepfake community on GitHub and identify as characterizing elements their capacity for abstraction from human subjects, dissociation from pornographic content, and an indifference to the harm caused. The use of technology to exercise the dominance of hegemonic masculinity as well as the lack of empathy and depersonalization of the "Other" (in this case the "Other” specifically referring to a woman) aligns deepfakers with gender trolls.

Gender trolling must be situated in a new antifeminist blacklash, a response to the Fourth Wave of Feminism and, in particular, the manosphere (Nagle, 2017; García-Mingo et al., 2022), a misogynist subculture on the Net highly reactive to gender issues and women's public expression, which functions as a sort of digital collective intelligence (Levy, 2004) to attack and silence those women who speak out publicly (on and off the Net), especially those with positions in favor of equality or who denounce sexist violence. This particularity places women in politics -understanding as such leaders, representatives and candidates of political parties, but also activists- in the crosshairs of these trolls (Piñeiro-Otero and Martínez-Rolán, 2021).

Cole (2015) points out the existence of similarities between trolling and disciplinary rhetoric, insofar as trolls exercise violent practices against women to dissuade and discipline them, placing the body as the center of control, as well as the central axis of discourse in many of the practices of gender trolling (for example, all those manifestations of digital sexual violence, from pornovengeance to the dissemination of intimate images).

Even if authors Paananen and Reichl (2019) have found that fun is one of the main motivations also for gender trolls, Lone and Bhandari (2018) stress that when trolling involves an organized act with an ideological purpose, it becomes a deliberate attempt to silence dissenting voices. As Manne (2018) argues, misogyny is itself a political phenomenon.

In this regard, the purpose of this paper has been to analyze the fraudulent use of images as a form of gender trolling against women politicians. The hypothesis is that the manipulation of the image (static or audiovisual), either as a mockery or as disinformation, seeks to undermine the reputation and credibility of leaders, representatives and candidates and -therefore- should be understood as a manifestation of violence against women in politics.

2. Delving into the phenomenon of Deepfakes: social and political implications

2.1. Image processing

The word "photosó", derived from the famous photo processing program Photoshop (photo store), has become popular to refer to any photographic retouching. This manipulation involves a common practice, even unconscious in the case of smart filters, fluctuating between the overtly incongruous and the intentionally misleading (Thomas, 2014; Winter and Salter 2019).

The evolution of technology and, more specifically, of artificial intelligence has favored the sophistication of these practices. From automatic image retouching, present in camera applications on smartphones to more complex formulas such as deepfakes, the current context offers an extensive panorama of challenges and opportunities to be explored (Chesney and Citron, 2018).

Deepfakes -a term that refers to deep learning- represent one of the most significant developments in digital manipulation. This phenomenon has flooded media and networks, integrating itself into the fabric of today's algorithmic culture (Hallinan and Striphas, 2016; Jacobsen and Simpson, 2023). Its initial application, the transposition of women's faces on other people's bodies, has in pornography a fertile ground (Compton, 2021). It is an invasion of privacy that has favored the ethical and legal debate around these creations (Ajder et al., 2019) regardless of the pathological additions that their use can generate (López et al., 2023).

For Kietzman et al. (2020) deepfakes have redefined image manipulation by allowing the hyper-realistic -and practically imperceptible- overlay and generation of audiovisual content. Beyond a hyper-specialized audience, their production is within the reach of the general public. A multitude of Freemium APPs can be downloaded from mobile application stores, such as Reface, which allows the replacement of faces in a video at the touch of a button.

The possible verisimilitude of these manipulations threatens the idea of the image as irrefutable proof, generating some concern regarding their use in the context of disinformation, while transforming the truth into a mutable reality (Schick, 2020; Yadlin-Segal and Oppenheim, 2021). The fluidity and familiarity of deepfakes favors their reception, regardless of their veracity, exacerbating this phenomenon (Vaccari and Chadwick, 2020).

The technological evolution in this field has triggered a wave of explicit and misleading material on the Internet as well as the demand for more rigorous regulations dealing with the creation and identification of these digital productions, as well as more advanced tools for their detection (Patrini et al., 2018).

In fact - as stated by Temir (2020) - the public notoriety of deepfakes increased after the appearance of videos of public personalities in compromising or fake situations; as warned by Mark Zuckerberg generated by artificial intelligence, deepfakes can generate disinformation and alter perceptions (Posters, 2019), eroding trust in the media, institutions and threatening the integrity of democratic processes (Diakopoulos and Johnson, 2020).

However, not all is negative. In February 2020, on the eve of the elections to the Delhi legislative assembly, a video of Indian politician Manoj Tiwari speaking Haryanvi (one of the more than 1,600 dialects spoken in India) was made viral by artificial intelligence. This deepfake, which reached fifteen million people, was the first example of its use for electoral communication (del Castillo, 2020).

In its creation, three of the techniques that Farid et al. (2019) identify in the creation of deepfakes were developed:

- Face replacement or changing the face of one person for another.

- Replication of facial expressions, which usually provide realism to the copy in addition to interpreting and vocalizing a fake speech.

- Voice synthesis, which allows the creation of an infrastructure capable of reproducing any text with the vocal and prosodic characteristics of the original model.

These authors point out an additional category - the generation of faces, a process that allows the creation of ex novo faces - among the most frequent production practices.

The democratization of applications for the production of these synthetic images has facilitated their creation and boosted their circulation which, beyond platforms such as Reddit or specific pages such as MrDeepfakes or AdultDeepfakes, today intrude into people's daily lives through WhatsApp.

Situated at a critical point between technological and social innovation, deepfakes bring back to the forefront the classic debate regarding the limits of creative expression and the protection of truth and individual privacy; of institutions, security and personal rights (Jacobsen and Simpson, 2023; Vaccari and Chadwick, 2020; Chesney and Citron, 2018).

2.2. Deepfake and disinformation

In the current context post-truth has positioned itself as a disruptive element in the socio-political sphere, blurring the boundaries between objective reality and fictional construction (Keyes, 2004). Practices such as clickbait, headlines generated to attract users (García-Orosa et al., 2017), the algorithmic preeminence of the most shocking or radical messages in social networks (Bellovary et al., 2021), the proliferation of pseudo-media (Rodríguez-Fernández, 2021) and political polarization, generate a breeding ground for the rise of disinformation in which the very notion of truth lacks relevance.

The concept of "post-truth" gained relevance on the global stage in 2016, coinciding with the Brexit referendum and the U.S. presidential elections, which led to its selection as word of the year by the Oxford English Dictionary. Both political events, the United Kingdom's exit from the European Union and Donald Trump's tumultuous presidential race, were permeated by narratives that often left factual accuracy at the expense of rhetorical strategies that appealed to the visceral emotions of the citizenry (McComiskey, 2017; Mula-Grau and Cambronero-Saiz, 2022).

In an increasingly complex and polarized context, the circulation of false, partial or misleading information has increased, amplified by different agents -politicians, media, etc.-, especially through social networks (Barrientos-Báez et al., 2022) that seek to influence and achieve a favorable public opinion.

The outbreak and management of COVID-19 led to an infodemia that made it difficult to locate reliable sources and content (Román-San-Miguel et al., 2020; Orte et al., 2020; Alonso-González, 2021; Renó et al., 2021; Barrientos-Báez et al., 2021; López-del-Castillo-Wilderbeek, 2021; Martínez-Sánchez, 2022; Román-San-Miguel et al., 2022; Nuevo-López et al., 2023), which generated the breeding ground for misinformation and rumors, the interested manipulation of information, which spread like a virus through social networks ( Organización Panamericana de la Salud, 2020) even though there were pre-pandemic precedents (Encinillas-García and Martín-Sabarís, 2023).

The high penetration of connected mobile devices and social media has led to the spread of false or distorted information among a very wide audience (Sim, 2019), which increasingly relegates its information consumption to the algorithms of social networks, search engines or news aggregators. Following the Digital News Report (Amoedo, 2023) in Spain 56% of people under 44 years of age already have in social networks their main source of information, although this also has a kind face (Vázquez-Chas, 2023) or useful (Abuín-Penas and Abuín-Penas, 2022) in crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic that should not be forgotten.

This information manipulation takes sophisticated forms, such as the intensive use of bots and trolls, which have become fundamental elements in disinformation campaigns in the vast world of social networks (Cosentino, 2020).

In the midst of technological evolution, the distinction between genuine and fabricated content has become a complex task, especially in the case of deepfakes, digital artifacts capable of recreating scenarios and altering the visual register, making virtual clones appear in situations or pronounce speeches not experienced by their real referent -person- (Westerlund, 2019). The democratic threat posed by these types of practices has led companies such as Facebook to ban this type of content, especially during critical electoral periods (Facebook Newsroom, 2020). Google, in its fight against disinformation, launched "Assembler" a model to detect false, manipulated images and deepfakes (Hao, 2022; Barca, 2020).

But the problem transcends deepfakes. Disinformation adopts multiple disguises, from misattributed quotes to digitally altered images and fabricated contexts, contributing to an ecosystem where truth becomes elusive and malleable (Almansa-Martínez et al., 2022). In the political communication scenario, platforms that perpetuate these fraudulent contents have taken a central role, forging parallel realities that are strengthened in the digital sphere (Rodríguez-Fernández, 2021).

An example that captured worldwide attention was the fake videos of Nancy Pelosi, Democratic politician and Speaker of the House of Representatives in the United States, edited to make it appear that she was speaking erratically, with diction difficulties and with an affected voice. Both videos, shared by then President Donald Trump and Rudy Giuliani (former mayor of New York) appeared to refer to a Pelosi afflicted with ethylic symptoms which led to a severely misrepresented public perception (Gómez-de-Ágreda et al., 2021; Harwell, 2019).

Given this deluge of misinformation, data verification is shaping up as an essential component of the information process (López-Borrull et al., 2018; Ufarte-Ruiz et al., 2022). Emerging technologies, from data mining in social networks to virtual reality, are reshaping the way we interact with information (Barrientos-Báez and Caldevilla-Domínguez, 2022) and present both opportunities and threats in this ongoing struggle for the veracity of sources (Manfredi-Sánchez, 2021; Miller, 2020).

At a time of intense polarization (Garmendia et al., 2022), in which gender issues have become polarizing tropes in political discourse (García Escribano, et al., 2021), reflecting an anti-feminist backlash that is spreading through online platforms and spaces (Ging and Siapera, 2019), factchecking represents an exceptional formula to prevent misogynist false narratives from permeating citizens and altering their perception of reality (Piñeiro-Otero and Martínez-Rolán, 2023).

2.3. Deepfakes in the political arena

One of the areas in which deepfakes have the greatest reach and notoriety is politics, since it is very sensitive to the information circulating through the new communication channels: social networks, where 2.0 is already a habitual resident (Caldevilla-Domínguez, 2014). The importance of public image and credibility in political actors make them especially vulnerable to this form of attack, but it can also affect the stability of the political process as a whole.

In the current climate of polarization and continuous tension in politics (Fiorina et al., 2006), the use of incorrect, false or inaccurate information to support ideas and/or arguments has become widespread. Thus, in the Spanish context, the television debates of candidates and political leaders prior to the general elections of July 2023 placed verification entities such as Maldita or Newtral as essential agents in the electoral framework, given the capacity of factchecking to significantly influence the attitude and evaluation of the candidacies (Wintersieck, 2017).

The generation of synthetic content is a disruptive change by creating events and statements that never happened. Barely a month into the Russia-Ukraine War, a deepfake video of President Volodymyr Zelensky calling for the surrender of the Ukrainian army and people was made public. Although the video was crudely made, and after its removal by Meta and YouTube (Jacobsen and Simpson, 2023), its dissemination highlighted the erosion of trust in authentic media (Wakefield, 2022).

Figure 2: Deepfake of the president of Ukraine calling for the surrender of the Ukrainian people.

Source: Verify.

These synthetic contents have reached such a level of sophistication that fabricated statements are almost indistinguishable from real ones, which has led to a focus on their ability to disrupt elections and undermine public trust (Chesney and Citron, 2018). Thus, deepfake stands as an alarming evolution in the dynamics of fake news. Although they have not yet had a prominent presence in electoral campaigns (Raterink, 2021), the possibility of generating this synthetic content adds a layer of complexity to the way information is generated and consumed in society.

Today disinformation has become a political strategy to alter public opinion but also to discredit and delegitimize opponents (Shao, 2020; Farkas and Schou, 2018). Examples are the manipulated videos of Nancy Pelosi (2019) or Patricia Bullrich (2020) -former Argentinean Minister of Security and one of the leaders of the coalition Juntos por el Cambio- that simulate states of drunkenness or incompetence, in order to discredit them politically. Although the term deepfake has come to refer to any digitally manipulated audiovisual piece, in the specific case of Pelosi and Bullrich they are shallowfakes: disinformative alterations of pre-existing video pieces to validate a non-truth (Randall, 2022).

Bakir and McStay (2018) describe this phenomenon as "floating meaning," where fake news has become a flexible and strategically tailored tool for shaping public perception and setting political agendas. These tactics have even infiltrated reputable media outlets The Washington Post, The Guardian or The New York Times, complicating citizens' ability to discern between reality and fabrication (Farkas and Schou, 2018). Thus, as Farkas and Schou (2018) point out deepfakes reinforce recurring discourses that support specific agendas, marking a new frontier in which truth is more elusive than ever.

Vaccari and Chadwick (2020) highlight that more than direct deceptions - in some cases the quality of manipulation facilitates their identification as false - deepfakes have the risk of feeding societal indeterminacy and cynicism, posing a challenge to online civic culture.

Beyond misinformation, the concern lies in how deepfakes can alter the perception of objective reality, fostering subjective realities fueled by fabricated 'facts' (Chesney and Citron, 2018).

The emergence of deepfakes, therefore, does not weaken the foundations of shared facts and truths, but rather reminds us that notions of democracy have never been fixed (Heemsbergen et al., 2022). In this context, as Jacobsen and Simpson (2023) argue, deepfakes are not a destabilizing phenomenon, but a reflection of the always contested nature of politics.

2.4. Deepfakes and pornographic exploitation

Since its first application stripping actresses and other celebrities, porn has established itself as prime territory for deepfakes. A study developed in 2019 by DEEPTRACE concluded that 96% of the audiovisual deepfakes in circulation were pornography based on the superimposition of women's faces-mostly celebrities such as Kristen Bell and Gal Gadot (Angler, 2021)-on porn actresses' bodies by artificial intelligence. This intense production of pornographic deepfakes was again highlighted in a recent report published by Home Security Heroes, 2023. This replacement has given rise to a new form of digital sexual abuse that, in addition to lacking the consent of the "protagonists," is particularly intrusive.

As van der Nagel (2020) points out, almost all of these synthetic videos engage women in non-consensual acts, usurping their agency as well as infringing on their privacy and intimacy. Here, deepfakes are more than images: they are weapons that reinforce objectification and the patriarchal gaze (Mulvey, 1989), rendering female bodies as mere materials at the service of male fantasies (Denson, 2020). Even when it comes to digital clones, the integration into these synthetic contents strips women of their visual representation as well as their social, cultural and physical environment, producing a profound dissonance between women's lived experience (reality) and the ways in which they are visually represented and manipulated by algorithms (Denson, 2020).

The manipulation of images for pornographic purposes, including as part of sexual violence such as sextortion or pornovengeance toward anonymous women, is not a new phenomenon. Hayward and Rahn (2015) place its beginnings in the mid-1990s, coinciding with the democratization of image editing software, a work that has taken a qualitative leap with the integration of artificial intelligence in the production and distribution of non-consensual porn.

The close links between the deepfake community and the manosphere are evident in platforms such as Reddit where anonymous users debate and share, as a learning community, regarding the use of photographs of ex-girlfriends in sexually explicit situations (Hayward and Rahn, 2015) allow advancing an exponential growth of these contents (Morris, 2018).

Meanwhile, research to achieve greater realism in these synthetic contents advances, focusing on algorithmic accuracy and representational perfection rather than on their ethical implications. Once again, a neutral perspective is proposed for a phenomenon - as with other digital practices - reinforces power structures and gender inequalities.

Deepfakes are not anomalies, but extensions of a pre-existing cultural structure, a reflection of a male gaze that - as Brown and Fleming (2020) point out - is now encoded in algorithms to present a reality that, far from the authenticity of the images, is based on patriarchal perpetuation, reinforcing power disparities.

For Jacobsen and Simpson (2023) deepfakes could be defined in Louise Amore's (2020) words about algorithmic accounts: "partial, contingent, oblique, incomplete, and unsubstantiated." They are flawed narratives, but not random: they are the fruits of tensions, fears, and power structures embedded in our social fabric (Jacobsen and Simpson, 2023).

2.5. Classification of fake images

Deepfakes, emerging in the midst of technological innovation, have become a tool with unprecedented power to shape public perception and construct alternative realities, navigating through the oceans of media representation and digital activism. In this sense, its relationship to the history of visual manipulation is not an anomaly, but rather an evolutionary successor to practices that date back decades or even centuries. Photographic manipulation has been an extensively used propaganda tool, drawing a historical parallel to today's deepfakes (Jaubert, 1989).

From a technological perspective, the bifurcation between deepfakes and cheapfakes is contingent on the accessibility of reality distortion tools and applications and - in some cases - the provision of a set of images that allow the generation of a digital clone as realistic as possible. The visibility of public personalities and their gluing with hundreds of images on the Net, makes them propitious victims of these digital forgeries.

The democratization of deepfakes applications is both fascinating and alarming (Tan and Lim, 2018). Today, the creation of deepfakes only requires a device with an Internet connection, a reality that-as pointed out by Gómez-de-Ágreda et al. (2021) - would have seemed like Science Fiction just a decade ago. The response to this phenomenon, however, cannot be limited to technological detection and moderation. Authors such as Garimella and Eckles (2020) and Gómez-de-Ágreda (2020) stress the need for recontextualization and critical analysis of information.

In fact, although the emergence of these technologies and their democratization has expanded the term deepfake as a general term for any fraudulent use of the image, regardless of the intervention of artificial intelligence in the process or the treatment implicit in the false or partial representation of "reality". In this sense, it is necessary to point out that beyond any technical manipulation, the very selection of the shot, the framing or the identification with another time/place with respect to the original are common practices in disinformation.

Authors such as Paris and Donovan (2019), Garimella and Eckles (2020) or Gómez-de-Ágreda et al. (2021) describe these image manipulation practices (audiovisual statics), from decontextualization, which seeks an interested reading of the image through framing or misattribution, to the technological sophistication of audiovisual deepfakes.

Along these lines, Gómez-de-Ágreda et al. (2021) propose an intensive classification of contemporary forms of disinformative manipulation of images. Categorization that suggests a gradation of these manifestations:

- Decontextualized images. Use of doubles or the attribution of the image content to a time or place different from the digital content. This is a frequent disinformation tactic that has favored the periodic circulation of stock images as snapshots of a current event.

- Partial images. Those that, while maintaining the context, present a partial view of reality - framing or interested perspective, cropping of the image, etc. - that leads to an erroneous reading of what is shown. In this regard, Gómez-de-Ágreda et al. (2021) defend the consideration of these images as a category different from the decontextualized ones.

- Retouched images/videos, including speed alterations that may lead to suggest erroneous readings of reality. The retouched video of Nanci Pelosi or the Argentinean Minister of Public Security, to suggest a possible state of drunkenness, for example, would fall into this category.

- Images/videos digitally altered, through retouching programs. They represent a further step in this manipulation by affecting the visual representation, i.e., the pixels of the images.

Figure 3: Decontextualized image. Image from a project by Saudi photographer Abdul Aziz Al-Otaibi, who went viral in 2014 as a Syrian child sleeping among the graves of his parents.

Source: Newtral.

Figure 4- 5: Partial image. Framing and interested perspective of the Telemadrid Debate between two mayoral candidates: Esperanza Aguirre and Manuela Carmela. Image 4, a still from a video published by El País, shows an apparent rejection of Carmena's greeting, while image 5, from the EFE agency, offers a different perspective.

Source: El País and EFE.

Figure 6- 7: Pixel retouching at the October 1, 2017, demonstrations.

When this digital alteration involves convolutional or generative neural networks to generate deep changes, it produces a qualitative leap in terms of sophistication and disruptive potential. These authors propose the breakdown of the deepfake category into two:

• Retouching of pre-existing images-for example face replacement or replication of facial expressions. This is the most common manifestation of deepfakes, both in the field of pornography and in the field of politics or disinformation -as happened in the case of the Ukrainian President- with application also in areas such as humor or advertising. An example of this is the Cruzcampo campaign "Con mucho acento" starring a synthetic Lola Flores thanks to facial replacement techniques.

• Ex novo creation of GAN images -generative adversarial network- of great realism in their representation (Hartman and Satter, 2020). In 2019 Phillip Wang developed a code based on the Nvidia algorithm that he named StyleGAN. This code gave rise to the website ThisPersonDoesNotExist.com, which generates extremely realistic fake faces through generative adversarial network. These images are indistinguishable, as Nightingale and Farid (2022) found, and can even generate more trust than real ones.

Figure 8: Still from Cruzcampo's advertising video "Con mucho acento" developed by Ogilvy and post-produced at Metropolitana.

Source: Panorama Audiovisual.

Figure 9- 11: GAN images automatically generated by ThisPersonDoesNotExist.com

Source: ThisPersonDoesNotExist.com

The explosion and democratization of the different forms of image manipulation have favored a change in its conception as a reliable reflection of reality. Today there is a context in which images represent an important part of disinformation. Deepfakes but -above all- decontextualization, partially truthful images or other manipulations to distort the interpretation of facts, suppose recurrent practices in the dissemination of information (Krizhevsky et al., 2017). Thus, photographs and videos have become a central part of the work of information verifiers.

While in some cases the task of these factcheckers is as simple as performing a reverse Google search, or reviewing other snapshots of the same event, the introduction of artificial intelligence complexifies this task to the point of making it practically impossible.

The reality-altering sophistication of these methods, where technologies such as convolutional neural networks and synthetic methods, is reshaping the frontier of what is possible (Barnes and Barraclough, 2019). The speed of development and penetration of these technologies in our media consumption (Gerardi et al., 2020), makes them an unprecedented threat because of their ability to replicate reality to an indistinguishable degree (Gómez-de-Ágreda et al., 2021).

2.6. Misogynist use in the political sphere

Within the political and social field, the emergence of deepfakes and other forms of image manipulation, as well as their viral potential through social platforms, represent a counter-informative attack. In a context in which social networks have positioned themselves as the main source of information in certain age groups (Amoedo, 2023), a propitious field for disinformation is generated, especially if we take into account phenomena of information restriction typical of these online environments such as the echo chamber or the bubble filter (Piñeiro Otero and Martínez Rolán, 2021).

These altered images, especially those with a high emotional component, become perfect content for rapid, almost unthinking consumption and distribution, fostering political polarization and undermining trust in media and institutions (Fard and Lingeswaran, 2020).

In a context of anti-feminist blacklash, in which gender issues have become polarizing tropes in political discourse (García Escribano et al., 2021), it is necessary to emphasize the existence of gender disinformation that will also be present in various forms of image manipulation. This treatment should be understood as part of gender trolling and, therefore, as part of a misogynist hate speech that, although it may have its origin in the manosphere, expands or feeds on the prevailing environmental sexism inside and outside the Net, and especially on a conservative reaction to the advances of women in public spaces.

This manosphere implies an intelligent crowd, along the lines pointed out by Rheingold (2002): it is an efficient organization -both of the creation process and of the flow of content- allowing people to connect with each other or with other people, acting in a coordinated way for its greater projection (and injuriousness).

In the case of female politicians, the boundaries between disinformation, politics and pornography, the three main areas in which image manipulation occurs, are blurred.

For example, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, U.S. Congresswoman (the youngest woman to hold this office), was the victim of various image manipulations, from a fake video of an alleged video call with Nancy Pelosi and Joe Biden after the assault on the Capitol, whose audio was manipulated with artificial intelligence putting in his mouth (badly synchronized) expletives to the Speaker of Congress and the President of the United States (Reuters Fact Check, 2023), to photographs in which he walks hand in hand with Elon Musk CEO of Twitter (University of Toronto, n. f.), passing through dozens of porn deepfakes in which, by the magic of artificial intelligence, Ocasio-Cortez performs various sexual fantasies of her creators.

Figure 12- 13: Image manipulation by Alexandria Ocaso-Cortez.

Source: University of Toronto and Reddit.

The synthetic creation of images and manipulation must be understood within a power struggle in which, as Ferrier (2018); Cuthbertson et al. (2019) point out, hate ideology, misogyny and false narratives converge.

This hostility against women politicians has been analyzed as part of an anti-feminist backlash, characterized by extreme misogyny, reactivity and an increased propensity for personal attacks (Bonet-Martín, 2020). As a countermovement, this antifeminism is characterized by its refined discursive sophistication, its remarkable capacity to evolve and adapt to different contexts and by the specific dialectic it develops in response to feminist demands and demonstrations (Bonet-Martí, 2021). In this tenor, Ging (2019) warns of a worrying shift from activism to personalized aggression, evidencing a change in the nature of the attacks suffered by women who occupy spaces of power and decision-making.

It is no coincidence that Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has declared herself a feminist and has used her speeches in Congress -such as the one in July 2020- to criticize the prevailing machismo and the normalization of violence and violent language against women (ElDiario.es, 2020).

The creation, treatment and dissemination of images of women politicians (in the broadest sense of politics) is usually aimed at discrediting them, undermining their credibility, their positions or inhibiting their participation. Thus, the ulterior aim of pornographic deepfakes against personalities such as the Indian journalist Rana Ayyub -after denouncing the rape of a young girl-, the British activist against child pornography, Kate Isaacs, or the environmental activist Greta Thumbert, is to silence their critical voices (Ayyub 2018; Citron 2019; France 2018; Mohan and Eldin 2019).

My work, which included revealing a scandal in a major murder investigation, caused altered images of me in sexualized poses to circulate online. The publication of my book led to accusations on social media about unethical methods and relationships with my sources. These events transformed me. The irony lies in the fact that just before the video came out, I had heard about the risks of deepfakes in India, a term I had to Google. To my misfortune, I became a victim a week later. I opted for silence initially, fearing that talking about the topic would only lead to morbid curiosity, catapulting the popularity of deepfakes. (Ayyub, 2018)

These false images, the product of artificial intelligence and other forms of manipulation, have become tools to attack women online. Their goal of silencing them leads to understanding these practices as part of violence against women politicians online or gender-based political violence (Hybridas, 2021).

Despite the prevalence of pornographic deepfakes (Ajder et al., 2019, Home Security Heroes, 2023), public and critical attention often focuses disproportionately on political deepfakes, minimizing the harm perpetrated with fake pornography. In the case of female politicians, these invasions of sexual privacy and image-based forms of sexual abuse (Citron 2018; Powell et al., 2018; Franks 2016; McGlynn and Rackley, 2017) of devastating consequences for victims (Siegemund-Broka, 2013; Citron, 2019; Melville, 2019), in addition to reinforcing existing norms and power structures by objectifying women and challenging their credibility (Andone 2019).

In this sense, following Krook and Retrepo (2016), it is necessary to speak of violence against women in politics as a specific phenomenon and different from other forms of male violence since it aims to prevent, punish or deprive their political participation because they are women (South Asia Partnership International, 2006).

Maddocks (2020) found that some creators of deepfakes deliberately use manipulated videos to silence prominent personalities. If, as Newton and Stanfill (2020) point out, a toxic geek masculinity is evident in the deepfake community, which propagates invasion of privacy and sexual exploitation online, its creation, as well as other forms of image manipulation, will mainly target women and -within these- those of greater public projection such as politicians.

In this sense, the aim of this paper has been to analyze the usual practices of image manipulation of which Spanish female politicians are victims, as part of the violence against women in politics.

3. METHODOLOGY

In order to address the forms of manipulation to which the images of women are subjected, a study was carried out in three stages, each with different information gathering techniques.

Within the AGITATE project: gender asymmetries in digital political communication, in which this study is part of, fifteen in-depth interviews were conducted with political leaders and representatives of various parties and areas (national-autonomous-local). In these interviews, the different forms of digital violence they face in their day-to-day work on the web, as well as their perceptions regarding gender as an explanatory factor, were analyzed.

While there is no consensus on whether the violence faced by female politicians is greater than that of their male counterparts, all interviewees pointed to the specificity of the violence: "men are attacked more for what they say, women for what they represent", "it attacks the private", "the most intimate", some of them also impact on objectification and sexualization, unthinkable in male politicians.

The next step was to focus on the specific field of image, to which some of them referred during the interview. They report having been subjected to memes, manipulation of images to highlight some physical trait, hypersexualization, and they even report having witnessed events that were later reinterpreted thanks to the manipulation of images.

Taking into account that false or manipulated images have become a fundamental part of news verification work, we have turned to image-based content identified as false by factcheckers such as Newtral, Maldita or VerificaRTVE.

Given the exploratory nature of this research, we opted for the selection of those images classified as false that involved women in the field of politics, instead of making a time limit for a systematic analysis of the information.

Therefore, although an extensive perspective of the concept of politicians has been developed, which includes leaders, candidates, representatives, militants or activists, the focus on news verifiers has introduced a double bias in the study images: focusing mainly on national level politicians and members of the central executive, representatives and leaders with greater public visibility, especially in a year, such as 2023, marked by elections and political negotiations.

Along the same lines, the search on adult deepfakes pages and platforms focused primarily on national-level politics, given the impossibility of covering all the names and personalities of local politics.

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The study carried out has revealed the limited sophistication in the manipulation of images of female politicians. In a context in which the use of artificial intelligence for face replacement, imitation of facial expressions or image-sound processing has multiplied, most of the images classified as false could be detected by a critical audience by doing a reverse Google search or reviewing other images of the same event, for example.

If the classification proposed by Gómez-de-Ágreda et al. (2021) is tañken as a reference, most of the images reviewed by the verifiers would correspond to partial images, followed by images with basic retouching and decontextualized images. All of them are manifestations of cheapfakes.

Figure 14: Decontextualized image. Minister of Equality and members of her team in Times Square.

Source: Vocento.

In July 2022, some snapshots of Irene Montero and her team in New York were disseminated. With them, the idea that it was a "pleasure" trip was spread, boosting the visibility of casual and casual photographs to the detriment of the agenda of official and institutional events.

Figure 15: Partial image. The "peak" between Yolanda Díaz and Pedro Sánchez.

The greeting of the President of the Spanish Executive, Pedro Sánchez, and the leader of Sumar, Yolanda Díaz, in a session of Congress in April 2022, became a different image -more affectionate- thanks to the perspective from which it was taken. This image was re-released in August 2023, after the so-called "Rubiales Case".

Figure 16: Basic video retouching: Isabel Díaz Ayuso drunk.

Source: Verifica RTVE.

Like Nancy Peloso and Patricia Bullrich, videos were circulated of Madrid President Isabel Díaz Ayuso and the Minister of Labor and leader of the leftist platform Sumar, in which a touch-up in the speed of the video suggested a clear state of drunkenness.

Figure 17: Digital image retouching: Vote of Ángela Rodríguez, Secretary of State for Equality and against Gender Violence.

Irene Montero's name is included in the ballot as if Ángela Rodríguez included her in her vote as head of the Sumar list.

Figure 18: Digital image retouching: hypersexualization of the president of the Community of Madrid, Isabel Díaz Ayuso.

In the case of deepfakes, a focus on the specific area of pornography can be seen. Although it can be presumed that there are other synthetic or synthetically modified images that have gone unnoticed by verifiers or that, despite being under suspicion, lack the tools to identify them as fake, it is on pornography platforms where most deepfakes of female politicians are found. Although some exceptions can be pointed out, such as the fake video of Macarena Olona dancing as Shakira, the most common formulas we find for this violation of the privacy of these women, through hypersexualization and the development of non-consensual pornography are: the (replacement of faces or changing the face of one person for another, and the replication of facial expressions, which usually provide realism to the copy in audiovisual pieces.

The creation of these deepfakes go beyond fantasies of intimacy with celebrities (Hayward and Rahn 2015), to involve exercises in public humiliation and retaliation for their sexual attractiveness (Newton and Stanfill, 2019) but - in the case of female politicians - for their transgression in taking the floor in the public-political space.

Figure 19- 21: Replacing faces of Caminando Juntos leader Macarena Olona and a young girl dancing to a Shakira choreography.

Source: @Clorazepamer.

Figure 22: Pornographic deepfake: Face replacement between Ciudadanos leader Inés Arrimadas and a porn actress.

Source: MrDeepfake.

In some cases this "revenge porn" is based on less sophisticated methods such as the decontextualization of images. This happened in the case of the Minister of Equality, Irene Montero, and the leader of Ciudadanos, Inés Arrimada, who were surreptitiously identified on digital platforms with two doubles: a sexologist and a porn actress.

Figure 23: Decontextualization: the alleged Irene Montero sexologist.

Source: VerificaRTVE.

If the content orientation is taken into account, it is noteworthy that, more than politics, these images are integrated into disinformation -gender disinformation (Piñeiro-Otero and Martínez-Rolán, 2022)- and even pornography.

As one of the interviewees pointed out, although in isolation these fake news "may seem funny because they are so grotesque (...) it is a fine rain strategy to discredit you".

Thus, these images are frequently catalogued as fake news, a term with which Gómez-de-Ágreda et al. (2021) emphasize the importance that -in the current context- certain content without news value acquires. At a time of excessive polarization of public opinion in Spain, the increase of this fake news and its free circulation through social networks seek to impact and appeal to emotion (Dafonte-Gómez, 2014) rather than reason, to arouse and reinforce certain positions.

One of the female politicians interviewed reflected on this aspect by pointing out that "soft politics (...) news and information on banal elements, displaces the debate on hard politics on real politics (...) the elements that operate on the material transformation of social reality".

But in the case of female politicians it is possible to go further, to link these fake news with a media tradition that gives a biased treatment -more trivial and familiar than that of their male colleagues (Sánchez-Calero et al., 2013; Palmer and Simon, 2005)- in which are frequent references to attire and physical appearance that tarnish the very actions and statements of female political representatives.

In this regard, some of the fake news are linked to the appearance and accessories of female politicians, as a way of discrediting their image and even their ideological positions.

Figure 24: Partial image. The Louis Vuitton handbag of the Minister of Equality. Viral photography and verification process.

Photograph of Irene Montero's appearance at the Equality Commission, in October 2021, to give an account of several projects underway in her Ministry, such as the law on the Comprehensive Guarantee of Sexual Freedom. The perspective from which it is taken, places next to Montero a branded handbag that -in reality- was behind her. That a minister has a two thousand euro Louis Vuitton handbag was an example of how the noise and information flows that feed political polarization are based on false news.

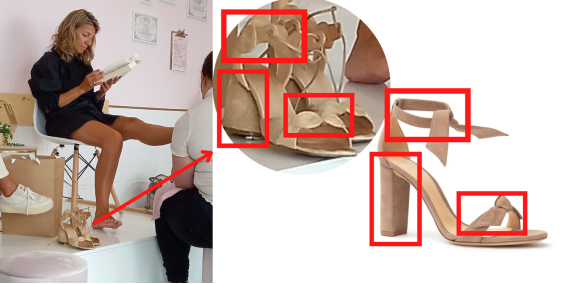

Figure 25: Decontextualized image. Yolanda Diaz's luxury footwear. Image and verification work.

Source: Newtral.

Misidentification of the model-brand of footwear of the Minister of Labor.

In this sense, the manipulation of images shows that this problem is neither new nor specific, but rather cultural, reflecting gender stereotypes and the power relations established inside and outside the network.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The irruption of deepfakes and other image manipulation techniques in the political and social sphere constitutes a major challenge for the veracity of information. In a scenario in which the public's perception can be distorted by the fluidity with which these contents are presented, regardless of their fidelity to reality, as Vaccari and Chadwick (2020) warn, the urgency of developing effective strategies for their identification becomes evident. However, it is even more imperative to strengthen the media education of citizens. Confronting confirmation bias, that impulse that leads us to accept only what resonates with our previous convictions, represents an arduous but indispensable task. And the fact is that, as Yvorsky (2019) postulates, cultivating a citizenry endowed with a critical spirit is essential to foster a reflective analysis of the torrent of information that besieges us.

Altered images, charged with intense emotions, stand as ideal tools for rapid and unbridled dissemination, thus fueling political polarization and undermining trust in media and institutions, a dynamic that Fard and Lingeswaran (2020) have thoroughly documented. This issue is exacerbated when directed at female politicians, whose integrity and participation are subject to exacerbated attacks in certain digital niches that belittle diversity and perpetuate anachronistic notions about gender and sexuality. Massanari (2017) warns that such attitudes are manifestations of a violent and sustained resistance against female advancement in technological and public spheres. In this hostile environment, so-called toxic geek masculinity, which Newton and Stanfill (2020) have described as a form of power that marginalizes and subjugates women, is particularly evident in aggression towards those who challenge patriarchal canons.

It is therefore imperative to understand that the proliferation of manipulated images of female politicians, often with the intention of undermining their reputations, is embedded in a context of power struggles in which misogynistic ideologies and fictional narratives are intertwined (Ferrier, 2018; Cuthbertson et al., 2019). These practices, often conflating into acts of pornovengeance, are used as a weapon to silence dissenting voices in an effort to preserve established power structures. It is no coincidence that these deepfakes and cheapfakes have focused on those women with greater preeminence such as Yolanda Díaz and Inés Arrimadas, leaders of political forces, or the President of the Community of Madrid Isabel Díaz Ayuso. In the case of Irene Montero or Ángela Rodríguez, beyond their public visibility, reference should be made to their character as symbols of equality policies and -therefore- they are propitious victims of misogynist attacks seeking to discredit them and denigrate their work.

Deepfakes and cheapfakes are a form of repression to silence women and confine them to certain soft spaces in politics, where their actions and speeches are hidden behind a halo of frivolity and fake news.

6. REFERENCES

Abuín-Penas, J. y Abuín-Penas, R. (2022). Redes sociales y el interés por la información oficial en tiempos de pandemia: análisis de la comunicación de los ministerios de salud europeos en Facebook durante la COVID-19. Revista de Comunicación y Salud, 12, 59-76. https://doi.org/10.35669/rcys.2022.12.e303

Ajder, H., Patrini, G., Cavalli, F. y Cullen, L. (2019). The state of deepfakes: landscape, threats, and impact. https://regmedia.co.uk/2019/10/08/deepfake_report.pdf

Almansa-Martínez, A., Fernández-Torres, M. J. y Rodríguez-Fernández, L. (2022). Desinformación en España un año después de la COVID-19: Análisis de las verificaciones de Newtral y Maldita. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 80, 183-200. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2022-1538

Alonso-González, M. (2021). Desinformación y coronavirus: el origen de las fake news en tiempos de pandemia. Revista de Ciencias de la Comunicación e Información, 26, 1-25. https://doi.org/10.35742/rcci.2021.26.e139

Amoedo, A. (2023). Disminuye el consumo de noticias en medios digitales y se estabiliza el uso de las fuentes tradicionales offline. Digital News Report España 2023. https://acortar.link/uPmSQX

Andone, D. (2019). Bella Thorne shares nude photos on Twitter after a hacker threatened to release them. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2019/06/15/entertainment/bella-thorne-nude-photos-hack/index.html

Angler, M. (2021). Fighting abusive deepfakes: the need for a multi-layered action plan. European Science-Media Hub. https://sciencemediahub.eu/

Ayyub, R. (2018). I was the victim of a deepfake porn plot intended to silence me. The Huffington Post. R https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/deepfake-porn_uk_5bf2c126e4b0f32bd58ba316

Bakir, V. y McStay, A. (2018). Fake news and the economy of emotions: problems, causes, solutions. Digital Journalism, 6(2), 154-175. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1345645

Barca, K. (2020). Google lanza Assembler, una herramienta para identificar imágenes falsas y combatir la desinformación en los medios. Business Insider. https://acortar.link/vBYRvV

Barnes, C. y Barraclough, T. (2019). Perception inception: Preparing for deepfakes and the synthetic media of tomorrow. The Law Foundation.

Barrientos-Báez, A. y Caldevilla-Domínguez, D. (2022). La mujer y las Relaciones públicas desde un alcance neurocomunicacional. Revista Internacional de Relaciones Públicas, 12(24), 85-102. https://doi.org/10.5783/revrrpp.v12i24.791

Barrientos-Báez, A., Caldevilla-Domínguez, D. y Yezers’ka, L. (2022). Fakenews y posverdad: relación con las redes sociales y fiabilidad de contenidos. Fonseca, Journal of Communication, 24, 149-162. https://doi.org/10.14201/fjc.28294

Barrientos-Báez, A., Martínez-Sala, A., Altamirano, V. y Caldevilla-Domínguez, D. (2021). Fake news: la pandemia de la COVID-19 y su cronología en el sector turístico. Historia y Comunicación Social, 26(Especial), 135-148. https://doi.org/10.5209/hics.74248

Beamonte, P. (2018). FakeApp, el programa de moda para crear vídeos porno falsos con IA. Hipertextual. https://hipertextual.com/2018/01/fakeapp-videos-porno-falsos-ia

Bellovary, A. K., Young, N. A. y Goldenberg, A. (2021). Left-and right-leaning news organizations use negative emotional content and elicit user engagement similarly. Affective Science, 2(4), 391-396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-021-00046-w

Bonet-Martí, J. (2020). Análisis de las estrategias discursivas empleadas en la construcción de discurso antifeminista en redes sociales. Psicoperspectivas, 19(3), 52-63. http://dx.doi.org/10.5027/psicoperspectivas-vol19-issue3-fulltext-2040

Bonet-Martí, J. (2021). Los antifeminismos como contramovimiento: una revisión bibliográfica de las principales perspectivas teóricas y de los debates actuales. Teknokultura. Revista de Cultura Digital y Movimientos Sociales, 18(1), 61-71. https://doi.org/10.5209/tekn.70225

Brown, W. y Fleming, D. H. (2020). Celebrity headjobs: Or oozing squid sex with a framed-up leaky . Porn Studies, 7(4), 357-366. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/23268743.2020.

Caldevilla-Domínguez, D. (2014). Impacto de las TIC y el 2.0: consecuencias para el sector de la comunicación. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 35, 106-127. https://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2014.35.106-127

Cerdán-Martínez, V., García-Guardia, M. L. y Padilla-Castillo, G. (2020). Alfabetización moral digital para la detección de deepfakes y fakes audiovisuales. CIC. Cuadernos de Información y Comunicación, 25, 165-181. https://doi.org/10.5209/ciyc.68762

Chesney, R. y Citron, D. (2018). Deep Fakes: A Looming Challenge for Privacy, Democracy, and National Security. California Law Review, 107, 1755-1820. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3213954

Citron, D. K. (2019). The National Security Challenge of Artificial Intelligence, Manipulated Media, and “Deep Fakes”. House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence. https://intelligence.house.gov/calendar/eventsingle.aspx?EventID=653

Cole, K. K. (2015). "It’s Like She's Eager to be Verbally Abused": Twitter, Trolls, and (En)Gendering Disciplinary Rhetoric. Feminist Media Studies, 15(2), 356-358. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2015.1008750

Compton, S. (2021). More women are facing the reality of deepfakes, and they’re ruining lives. Vogue. https://www.vogue.co.uk/news/article/stop-deepfakes-campaign

Cosentino, G. (2020). Social Media and the Post-Truth World Order: The Global Dynamics of Disinformation. Springer Nature.

Cuthbertson, L., Kearney, A., Dawson, R., Zawaduk, A., Cuthbertson, E., Gordon-Tighe, A. y Mathewson, K. W. (2019). Women, politics and Twitter: using machine learning to change the discourse. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1911.11025

Dafonte-Gómez, A. (2014). Claves de la publicidad viral: De la motivación a la emoción en los vídeos más compartidos. Comunicar, 21(43), 199-206. http://dx.doi.org/10.3916/C43-2014-20

Dawkins, R. (2006). The Selfish Gene (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

DEEPTRACE (2019). The state of Deepfakes. Landscape Threads and Impact. https://regmedia.co.uk/2019/10/08/deepfake_report.pdf

del Castillo, C. (2020). Un candidato que intenta captar votos en una lengua que no habla: los deepfakes políticos ya están aquí. El Diario.es. https://acortar.link/wle9aF

Denson, S. (2020). Discorrelated images. Duke University Press.

Diakopoulos, N. y Johnson, D. (2020). Anticipating and addressing the ethical implications of deepfakes in the context of elections. New Media & Society, 23(7), 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820925811

ElDiarioes [elDiario.es] (2020, July 24). Ocasio-Cortez responde a los insultos machistas de un congresista: "Esto no es puntual, es cultural" [video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x0Qt-zF6oAw

Encinillas-García, M. y Martín-Sabarís, R. (2023). Desinformación y salud en la era pre-COVID: Una revisión sistemática. Revista de Comunicación y Salud, 13, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.35669/rcys.2023.13.e312

Facebook Newsroom. (2020). Enforcing Against Manipulated Media. https://about.fb.com/news/2020/01/enforcing-against-manipulated-media/

Fard, A.-E. y Lingeswaran, S. (2020). Misinformation battle revisited: Counter strategies from clinics to artificial intelligence. En Proceedings of the WWW’20. https://doi.org/10.1145/3366424.3384373

Farid, H., Gu, Y., He, M., Nagano, K. y Li, H. (2019). Protecting world leaders against deep fakes. En proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (pp. 38-45). https://acortar.link/xA6CK1

Farkas, J. y Schou, J. (2018). Fake News as a Floating Signifier: Hegemony, Antagonism and the Politics of Falsehood, Javnost. The Public, 25(3), 298-314. https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2018.1463047

Ferrier, M. (2018). Attacks and Harassment: The impact on female journalists and their reporting. International Women's Media Foundation & Trollbusters. www.iwmf.org/attacks-and-harassment/

Fiorina, M. P., Abrams, S. J. y Pope, J. C. (2006). Culture War? The Myth of a Polarized America. Pearson.

France, L. R. (2018). Fans rally around Bella Thorne after sexual abuse revelation. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2018/01/09/entertainment/bella-thorne-sexual-abuse/index.html

Franks, M. A. (2016). 'Revenge Porn' Reform: A View from the Front Lines. Florida Law Review, 69(5). https://repository.law.miami.edu/fac_articles/572/

García-Escribano, J. J., García-Palma, M. B. y Manzanera-Román, S. (2021). La polarización de la ciudadanía ante temas posicionales de la política española. Revista Más Poder Local, 45, 57-73. https://acortar.link/qw5xOT

García-Mingo, E., Díaz Fernández, S. y Tomás-Forte, S. (2022). (Re)configurando el imaginario sobre la violencia sexual desde el antifeminismo: el trabajo ideológico de la manosfera española. Política y Sociedad, 59(1), e80369. http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/poso.80369

García-Orosa, B. (2021). Disinformation, social media, bots, and astroturfing: the fourth wave of digital democracy. Profesional de la Información, 30(6), e300603. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2021.nov.03

Garimella, K. y Eckles, D. (2020). Images and misinformation in political groups: Evidence from WhatsApp in India. Misinformation Review, 1(5). https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-030

Garmendia Madariaga, A., Lorenzo-Rodríguez, J. y Riera, P. (2022). Construyendo bloques: la promiscuidad política online en tiempos de polarización en España. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 178, 61-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.5477/cis/reis.178.61

Gerardi, F., Walters, N. y James, T. (2020). Cyber-security implications of deepfakes. University College London. NCC Group.

Ging, D. y Siapera, E. (2019). Gender hate online: Understanding the New Anti-feminism. Palgrave Macmillan.

Gómez-de-Ágreda, Á. (2020). Ethics of autonomous weapons systems and its applicability to any AI systems. Telecommunications Policy, 44(6). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2020.101953

Gómez-de-Ágreda, Á., Feijóo, C. y Salazar-García, I. A. (2021). Una nueva taxonomía del uso de la imagen en la conformación interesada del relato digital. Deep fakes e inteligencia artificial. El Profesional de la Información, 30(2), e300216. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2021.mar.16

Hallinan, B. y Striphas, T. (2016). Recommended for you: The Netflix prize and the production of algorithmic culture. New Media & Society, 18(1), 117-137. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814538646

Hao, K. (2022). Google has released a tool to spot faked and doctored images. MIT Technology Review. https://acortar.link/as9I9z

Hartman, T. y Satter, R. (2020). These faces are not real. Reuters Graphics. https://graphics.reuters.com/CYBER-DEEPFAKE/ACTIVIST/nmovajgnxpa/index.html

Harwell, D. (2018). White House shares doctored video to support punishment of journalist Jim Acosta. The Washington Post. https://wapo.st/3cytr6C

Hayward, P. y Rahn, A. (2015). Opening Pandora’s Box: Pleasure, Consent and Consequence in the Production and Circulation of Celebrity Sex Videos. Porn Studies, 2(1), 49-61. https://doi.org/10.1080/23268743.2014.984951

Heemsbergen, L., Treré, E. y Pereira, G. (2022). Introduction to algorithmic antagonisms: Resistance, reconfiguration, and renaissance for computational life. Media International Australia, 183(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X221086042

Home Security Heroes (2023). State Of Deepfakes: Realities, Threats, And Impact. www.homesecurityheroes.com/state-of-deepfakes/

Hybridas (2021). La violencia política por razón de género en España. https://acortar.link/F9KUKC

Jacobsen, B. N. y Simpson, J. (2023). The tensions of deepfakes. Information, Communication & Society. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2023.2234980

Jaubert, A. (1989). Making People Disappear. Pergamon-Brassey´s.

Keyes, R. (2004). The post-truth era: Dishonesty and deception in contemporary life. St. Martin's Press.

Kietzmann, J., Lee, L. W., McCarthy, I. P. y Kietzmann, T. (2020). Deepfakes: Trick or Treat?, Business Horizons, 63(2), 135-146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2019.11.006

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. y Hinton, G. E. (2017). ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Communications of the ACM, 60(6). https://doi.org/10.1145/3065386

Krook, M. L. y Restrepo, J. (2016). Violencia contra las mujeres en política. Política y Gobierno, 23(2), 459-490. https://acortar.link/PlrwE7

Levy, P. (2004). Inteligencia colectiva: por una antropología del ciberespacio. Centro Nacional de Información de Ciencias Médicas [INFOMED]. https://acortar.link/po9jLK

Lone, A. A. y Bhandari, S. (2020). Mapping Gender-based Violence through ‘Gendertrolling’. National Dialogue on Gender-based Cyber Violence. https://acortar.link/RDIOpx

López-del-Castillo-Wilderbeek, F. L. (2021). El seguimiento sobre las fake news en medios institucionales durante el coronavirus en España. Vivat Academia, 154, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.15178/va.2021.154.e1253

López Iglesias, M., Tapia-Frade, A. y Ruiz Velasco, C. M. (2023). Patologías y dependencias que provocan las redes sociales en los jóvenes nativos digitales. Revista de Comunicación y Salud, 13, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.35669/rcys.2023.13.e301

López-Borrull, A., Vives-Gràcia, J. y Badell, J.-I. (2018). Fake news, ¿Amenaza u oportunidad para los profesionales de la información y la documentación?. El Profesional de la Información, 27(6), 1346-1356. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2018.nov.17

Maddocks, S. (2020). ‘A Deepfake Porn Plot Intended to Silence Me’: Exploring continuities between pornographic and ‘political’ deep fakes. Porn Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/23268743.2020.1757499

Manfredi-Sánchez, J. L. (2021). El impacto de COVID-19 en la narrativa estratégica internacional. Instituto Español de Estudios Estratégicos. https://acortar.link/QPJBdF

Manne, K. (2018). Down girl: the logic of misogyny. Oxford University Press.

Mantilla, K. (2013). Gendertrolling: misogyny adapts to new media. Feminist Studies, 39(2). https://www.jstor.org/stable/23719068

Martínez-Sánchez, J. A. (2022). Prevención de la difusión de fake news y bulos durante la pandemia de COVID-19 en España. De la penalización al impulso de la alfabetización informacional. Revista de Ciencias de la Comunicación e Información, 27, 15-32. https://doi.org/10.35742/rcci.2022.27.e236

Massanari, A. (2017). #Gamergate and the fappening: how reddit’s algorithm, governance, and culture support toxic technocultures. New Media & Society, 19(3), 329-346. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448156088

McComiskey, B. (2017). Post-Truth Rhetoric and Composition. University Press of Colorado.

McGlynn, C., Rackley, E. y Houghton, R. (2017). Beyond ‘revenge porn’: The continuum of image-based abuse. Feminist Legal Studies, 25(1), 25-46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10691-017-9343-2

Melville, K. (2019). ‘Humiliated, Frightened and Paranoid’: The Insidious Rise of Deepfake Porn. ABC News. https://acortar.link/2uYkzm

Miller, M. N. (2020). Digital threats to democracy: A double-edged sentence. Technology for Global Security. CNAS. https://acortar.link/dWpD3x

Mohan, M. y Eldin, Y. (2019). The real (and fake) sex lives of Bella Thorne. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/stories-50072653

Morris, I. (2018). Revenge porn gets even more horrifying with deepfakes. Forbes. https://acortar.link/Qneid0

Mula-Grau, J. y Cambronero-Saiz, B. (2022). Identificación de las fake news que se publican en la edición en papel de un diario provincial en la era de la desinformación digital de Trump y el inicio del COVID. Vivat Academia, 155, 23-38. https://doi.org/10.15178/va.2022.155.e1329

Mulvey, L. (1978). Placer visual y cine narrativo. https://acortar.link/EjrhV1

Nagle, A. (2017). Kill all normies: online culture wars from 4chan and tumbler to trump and the alt-right. Zero Books.

Newton, O. B. y Stanfill, M. (2019). My NSFW video has partial occlusion: deepfakes and the technological production of non-consensual pornography. Porn Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/23268743.2019.1675091

Nightingale, S. J. y Farid, H. (2022). AI-synthesized faces are indistinguishable from real faces and more trustworthy. PNAS Journal, 119(8), e2120481119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2120481119

Nuevo-López, A., López-Martínez, F. y Delgado-Peña, J. J. (2023). Bulos, redes sociales, derechos, seguridad y salud pública: dos casos de estudio relacionados. Revista de Ciencias de la Comunicación e Información, 28, 120-147. https://doi.org/10.35742/rcci.2023.28.e286

Organización Panamericana de la Salud [OPS] (2020). Entender la infodemia y la desinformación en la lucha contra la COVID-19. Caja de herramientas: transformación digital. https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/52053/Factsheet-Infodemic_spa.pdf

Orte, C., Sánchez-Prieto, L., Caldevilla-Domínguez, D. y Barrientos-Báez, A. (2020). Evaluation of distress and risk perception associated with COVID-19 in vulnerable groups. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249207

Paananen, A. y Reichl, A. J. (2019). Gendertrolls just want to have fun, too. Personality and Individual Differences, 141, 152-156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.01.011

Palmer, B. y Simon, D. (2005). When women run against women: the hidden influence of female incumbents in elections to the U.S. house of representatives, 1956-2002. Cambridge University Press.

Paris, B. y Donovan, J. (2019). Deepfakes and Cheap Fakes: The Manipulation of Audio and Visual Evidence. Data & Society Research Institute. https://datasociety.net/output/deepfakes-and-cheap-fakes/

Patrini, G., Cavalli, F. y Ajder, H. (2018). The state of deepfakes: reality under attack. Annual Report, 2(3). https://acortar.link/tZ9Eyy

Piñeiro-Otero, T. y Martínez-Rolán, X. (2021). Eso no me lo dices en la calle. Análisis del discurso del odio contra las mujeres en Twitter. Profesional de la Información, 30(5). https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2021.sep.12

Piñeiro-Otero, T., Martínez-Rolán, X. y Castro, L. (2023). ¿Sueñan los troles con mujeres en el poder? Una aproximación al troleo de género como violencia política. [Comunicación presentada al congreso Meis Studes]. Brasil.

Powell, A., Flynn, A. y Henry, N. (2018). AI Can Now Create Fake Porn, Making Revenge Porn Even More Complicated. The Conversation. The Conversation. https://acortar.link/tZ9Eyy

Randall, N. (2022). The rise of shallowfakes. The Journal. The voice of your profession. https://thejournal.cii.co.uk/2022/10/20/rise-shallowfakes

Raterink, C. (2021). Assessing the risks of language model ‘deepfakes’ to democracy. Tech Policy Review. https://techpolicy.press/assessing-the-risks-of-language-model-deepfakes-to-democracy/

Renó, D., Martínez-Rolán, X., Piñeiro-Otero, T. y Versuti, A. (2021). COVID-19 e Instagram: uma análise das publicações ibero-americanas. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 54, 223-248. https://doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2021.54.e724

Reuters Fact Check (2023). Fact Check-Video features deepfakes of Nancy Pelosi, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Joe Biden. https://www.reuters.com/article/factcheck-pelosi-deepfake-idUSL1N36V2E0

Rheingold, H. (2002). Multitudes inteligentes. La próxima revolución social. Gedisa.

Rodríguez-Fernández, L. (2021). Propaganda digital. Comunicación en tiempos de desinformación. UOC.

Román-San-Miguel, A., Sánchez-Gey Valenzuela, N. y Elías-Zambrano, R. (2022). Los profesionales de la información y las fake news durante la pandemia del COVID-19. Vivat Academia, 155, 131-149. https://doi.org/10.15178/va.2022.155.e1312

Román-San-Miguel, A., Sánchez-Gey Valenzuela, N. y Elías-Zambrano, R. (2020). Las fake news durante el Estado de Alarma por COVID-19. Análisis desde el punto de vista político en la prensa española. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 78, 359-391. www.doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2020-1481

Sánchez-Calero, M. L., Vinuesa Tejero, M. L. y Abejón Mendoza, P. (2013). Las mujeres políticas en España y su proyección en los medios de comunicación. Razón y Palabra, 82. http://www.razonypalabra.org.mx/N/N82/V82/30_SanchezCalero_Vinuesa_Abejon_V82.pdf

Siegemund-Broka, A. (2013). ‘Storage Wars’ Star Brandi Passante Wins ‘Stalker Porn’ Lawsuit. The Hollywood Reporter. https://www.hollywoodreporter. com/thr-esq/storage-wars-star-brandi-passante-578047

South Asia Partnership International [SAP]. (2006). Violence against Women in Politics. Lalitpur. SAP-Nepal Publishing House.

Schick, N. (2020). Deepfakes: the coming infocalypse. Grand Central Publishing.

Shao, G. (2020). Fake videos could be the next big problem in the 2020 election. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/01/13/deepfakes-could-be-a-big-problem-for-the-2020-election.html

Silverman, C. (17 de abril de 2018). How to spot a deepfake like the Barack Obama-Jordan Peele video. BuzzFeed. https://acortar.link/QhRcSW

Sim, S. (2019). Post-Truth, Scepticism & Power. Cham: Springer Nature. https://acortar.link/8hUJqF

Tan, K. y Lim, B. (2018). The artificial intelligence renaissance: Deep learning and the road to human-level machine intelligence. APSIPA Transactions on Signal and Information Processing, 7, E6. https://doi.org/10.1017/ATSIP.2018.6