Revista Latina de Comunicación Social. 2025. No. 83, 01-25

The appropriation of the meme by the parties: fandom and propaganda in Spanish 2023 general elections

La apropiación partidista del meme: fandom y propaganda en las elecciones generales españolas de 2023

Ana I. Barragán-Romero

University of Seville. Spain.

Lucía Caro-Castaño

University of Cadiz. Spain.

Elena Bellido-Pérez

University of Seville. Spain.

![]()

ABSTRACT

Introduction: This research focuses on the appropriation of the meme as a propaganda strategy in an electoral campaign, placing it within the framework of politainment and the humanization of the candidate. Specifically, the work analyzes the redefinition of the “Perro Sanxe” meme in the Spanish general elections of July 2023. What began as an insult by the Spanish right towards the president of the government Pedro Sánchez, was resignified by the left and subsequently appropriated by the communication department of the PSOE. Methodology: The study presents an exploratory-descriptive methodological design that adopts critical discourse analysis on Pedro Sánchez's interventions in infotainment media. Additionally, two in-depth interviews have been carried out, one with Ion Antolín, director of the Communication Department of PSOE, and another with the user of Mr. Handsome, Pedro Sánchez's fandom account on X. Both techniques have been accompanied by a documentary review of the media coverage of “Perro Sanxe” during the campaign. Results: The results show that the resignification of the “Perro Sanxe” meme as a positive nickname was relevant in the electoral strategy of the PSOE, aimed at improving the image of its candidate and humanizing him, in response to the attack from the right, focused on ending “sanchism”. Discussion and conclusions: From the study, the importance of using humor as a propaganda tool is extracted, especially for vote activation, favoring an underdog effect in this case, and the use of guerrilla communication techniques to connect with younger voters.

Keywords: Political communication; meme; astroturfing; electoral campaigns; PSOE; Pedro Sánchez.

RESUMEN

Introducción: Esta investigación se centra en la apropiación del meme como estrategia propagandística en campaña electoral, situándola en el marco del politainment y la humanización del candidato. Concretamente, el trabajo analiza la resignificación del meme de “Perro Sanxe” en las elecciones generales españolas de julio de 2023. Lo que comenzó siendo un insulto por parte de la derecha española hacia el presidente del gobierno Pedro Sánchez, fue resignificado por la izquierda y posteriormente apropiado por la dirección de comunicación del PSOE. Metodología: El estudio presenta un diseño metodológico exploratorio-descriptivo que adopta el análisis crítico del discurso sobre las intervenciones de Pedro Sánchez en medios de infoentretenimiento. Complementariamente, se han realizado dos entrevistas en profundidad, una a Ion Antolín, dircom del PSOE, y otra a la usuaria de Mr. Handsome, cuenta fandom de Pedro Sánchez en X. Ambas técnicas han sido acompañadas por una revisión documental de la cobertura mediática de “Perro Sanxe” durante la campaña. Resultados: Los resultados demuestran que la resignificación del meme de “Perro Sanxe” como apelativo positivo fue relevante en la estrategia electoral del PSOE, orientada a mejorar la imagen de su candidato y humanizarlo, en respuesta al ataque de la derecha, centrada en acabar con el “sanchismo”. Discusión y conclusiones: Del estudio se extrae la importancia del uso del humor como herramienta propagandística, especialmente para la activación de voto, favoreciendo un efecto underdog en este caso, y del uso de técnicas de comunicación de guerrilla para conectar con los votantes más jóvenes.

Palabras clave: Comunicación política; meme; astroturfing; campaña electoral; PSOE; Pedro Sánchez.

1. INTRODUCTION

On June 26, 2023, Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez was asked in an interview on Cadena Ser about the nickname “Perro Sanxe,” a denomination that had been circulating since 2020 among the conservative electorate. At the time, Sánchez explained that “it is not pleasant” (Sánchez, 2023e). However, twenty days later, already in the middle of the election campaign and interviewed on the podcast La Pija y la Quinqui (Peguer and Maturana, 2023), it was Sánchez who joked about the “Perro Sanxe” meme. This change in the candidate's stance on a meme that had been circulating for several years among different digital communities points to a strategy of appropriation developed by the PSOE: the resignification of a meme that went from being a criticism of Pedro Sánchez to become a fundamental element of his own campaign for reelection in the general elections of July 23, 2023.

This is a classic strategy used by non-hegemonic collectives, such as the LGTBIQ+ community, for example, who have chosen to appropriate symbols and insults used against the collective to resignify them in their favor (Zaera et al., 2021). However, its use by political parties had already been observed in the Spanish left in 2023 by Sumar. Thus, on the occasion of the party's presentation, the organization distributed stickers of “La Fashionaria” among the sympathizers attending the event (Menéndez, April 2, 2023); this was a derogatory nickname created by Federico Jiménez Losantos for Yolanda Díaz that circulated among the candidate's detractors.

This study focuses on the usefulness of the meme as a propaganda strategy. Particularly, on a meme that had been created precisely as a criticism of the president of the government and that ended up being a key piece for his reelection in July 2023. The viral component of memes and their ability to reach a young audience, a priori disaffected with politics, make this type of messages a very effective propaganda tool. As Domenach already stated, “propaganda is polymorphous and has unlimited resources” (1986, p. 48), so that propaganda messages will always find a way to reach their audience. Thus, through two in-depth interviews, a critical analysis of the speeches of candidate Pedro Sánchez and a documentary review of newspaper articles on “Perro Sanxe”, this research addresses the importance of humor as a propaganda tool, highlighting it as a fundamental resource within a strategy of humanization of the candidate in the midst of an election campaign.

1.1. Propagandistic use of the meme

The formal properties of the meme (irony, exaggeration, use of language for insiders) make it a particularly effective format for conveying an indirect charge of empathy (Owen, 2019, p. 102). In an era of increasing anti-politics (Wood et al., 2016), the memetic game thus becomes a powerful tool to viralize messages and arouse an emotive response (Rodríguez, 2013; Shifman, 2011). This is possible thanks to the critical (Wiggins, 2019) and humorous (Davison, 2012) nature of the meme, characteristics that facilitate the creation of affective communities that recognize each other through their ability to interpret these messages (Owen, 2019). Hence, several studies have analyzed their propagandistic potential in electoral contexts both outside Spain (Burroughs, 2013; Moody-Ramirez and Church, 2019; McLoughlin and Southern, 2021) and within the country (Martínez-Rolán and Piñeiro-Otero, 2017; Meso-Ayerdi et al., 2017; Carrasco-Polaino et al., 2020; Ruggeri, 2022). Therefore, as Denisova states, memes “promote and oppose propaganda, they entertain, inform and educate” (2019, p. 5). Often, political memes are aimed at criticizing the rival (Zolides, 2022), although it is true that the fandom of the politician or politician concerned (Barnes, 2023; Caro-Castaño et al., 2024; Dean, 2017; Hernández-Santaolalla and Rubio-Hernández, 2017; Lee and Moon, 2021) can also appropriate and re-signify them. It is, precisely, in this line where this research is framed: how the PSOE fandom proposed an ideological shift of the “Perro Sanxe” meme, and how the party itself made it official during the July 2023 election campaign.

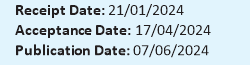

Many candidates are aware of the memetic potential of images and offer their own material to be transformed by network users (Martínez-Roldán and Piñeiro-Otero, 2016). In this sense, the authors highlight Obama as the “memecrat par excellence” (2016, p. 147). Moreover, just as users appropriate propaganda and eventually empty it of ideology to turn it into a meme (Kalkina, 2020), appropriation also occurs in the opposite direction and the political class can, in turn, choose pre-existing memes to use as propaganda tools. It happened in 2016 with “Pepe the Frog,” the meme that the American alt-right transformed and got Donald Trump to include in his campaign (Woods and Hahner, 2020). Something similar happened again in 2023 with the “Dark Brandon” meme, “which began as an ironic take on an already-ironic meme from the right,” but which “has become a triumphant anthem for the Biden campaign” (Romano, 2023). This case finds great parallels with the one analyzed here. The origin of “Dark Brandon” goes back to an interview that an NBC reporter was conducting with driver Brandon Brown after winning his first race at Talladega in October 2021; during that interview, the reporter translated the cries of the masses as: “Let's go, Brandon!”, instead of what they were actually shouting: “Fuck Joe Biden!”. This was embraced by Donald Trump supporters, who began circulating the phrase “Let 's go, Brandon!” turning it into a meme, making it code for attacking Trump's rival. However, Democrats soon managed to appropriate the meme through the creation of the character “Dark Brandon” (symbolizing the darker side of President Joe Biden), which directly alluded to the memetic language of “Dark MAGA”, “a subgenre of right-wing memeing that's aesthetically more nihilistic than even the typical ironic Trumpist meme” (Romano, 2023). Although it is not entirely clear whether the first to put “Dark Brandon” into circulation were the Republicans or the Democrats, it is certain that the root of the meme is a direct criticism of Joe Biden, a criticism that the Democrats managed to subvert to the point of integrating the meme into the president's campaign (Figure 1). The same thing happened in Spain and practically at the same time. The theoretical origins, in short, are similar to those of the case under analysis: the appropriation of “Perro Sanxe” was motivated by the resignification that progressive users were already making of the meme originally critical of Sánchez, especially from the last version that appeared in social media - “Más sabe el Perro Sanxe por perro que por Sanxe” The dog is wiser for being a dog rather than for being a Sanxe)?)- the day after the announcement of the electoral advance (del Corral, July 27, 2023).

Figure 1. Appropriation of the “Dark Brandon” meme by Democrats embedded in President Joe Biden's campaign.

Source:

President Biden [@POTUS], 2023, April 30. https://acortar.link/LE9dZJ

However, the meme is not the only element of appropriation used by political propaganda. In a study on the transnationality of memes used by the extreme right, McSwiney et al. (2021) considered that the meme is only one part of a whole broad digital visual culture. The authors point out that parties appropriate all kinds of symbols of popular culture in order to re-signify them. One example they raise is the criticism of confinement during the COVID-19 pandemic by appealing to the notion of hypervigilance from George Orwell's novel 1984.

1.2. The humanization of the candidate

The strategy of gently ironizing some feature of the candidate's personality in the context of an electoral campaign can be framed within a more general strategy typical of the modern and postmodern phase of political communication: the humanization of the candidate. Humanization should be understood, in terms of Van Aelst et al. (2012), as a mixture between individualization (the figure of the candidate as a fundamental piece of the campaign) and the privatization of the candidate (the display of a facet other than that of his or her public role). This is often achieved in social networks such as Instagram (Filimonov et al., 2016; Selva-Ruiz and Caro-Castaño, 2017; López-Rabadán and Doménech-Fabregat, 2018; Gordillo and Bellido-Pérez, 2021; Parmelee et al., 2022), where the image takes on fundamental importance.

The media-cultural context that frames this strategy of humanizing the candidate is infotainment or politainment (Nieland, 2008; Schultz, 2001), where, putting the ideological content of his messages in the background, the candidate allows himself to be seen in entertainment formats to show a version of himself different from the known professional one (McAllister, 2007; Campus, 2010; Bennett, 2012; Adam and Maier, 2010). In short, it is about using celebrification techniques (Street, 2004) to approach the audience, becoming what Wood et al. (2016) call an “everyday celebrity politician”. Whether in traditional media or in social networks, the idea is for citizens to be driven “more by a desire to see a particular plot outcome rather than deliberate consideration of what that candidate is likely to do in office” (McLaughlin and Macafee, 2019, p. 596). The idea, in short, is to bring humanity to the party's candidacy so that an audience (on many occasions, different from the audience accustomed to the candidate's speeches), empathizes with the person and not necessarily with the politician and his or her programmatic proposals. Precisely, as will be seen below, this was the strategy of Pedro Sánchez and his party before and during the electoral campaign for the 2023 general elections.

In this campaign, the PSOE developed a strategy focused on regaining control of the social conversation and mobilizing the progressive electorate through the hypervisibility of its leader after the electoral debacle of the PSOE in the municipal and autonomic elections of May 28, 2023, which led the politician to decide to bring forward the general elections (Cué, 2023). To this end, the socialist candidate gave interviews to the main infotainment programs in the country, both in traditional media and digital platforms. The present research applies discourse analysis to all of Sánchez's interviews during the months of June and July 2023, observing in them a clear argument in which Sánchez, on the one hand, dismantled the concept of “sanchismo” proposed by the Spanish right wing, while at the same time appropriating the “Perro Sanxe” meme. Along with this analysis, the study is complemented by two in-depth interviews with two key people in the electoral strategy of humanizing the candidate through the meme: Ion Antolín Llorente, the director of communication of the PSOE, and the anonymous user of the account Mr. Handsome on X, an account of the PSOE. Handsome in X, an account of humorous content dedicated to praise Pedro Sánchez and which currently has more than 81 thousand followers.

2. OBJECTIVES

The general objective (“GO”) of this research is to know the communicative strategy of appropriation of the meme “Perro Sanxe” developed by the PSOE on the occasion of the elections to the Spanish Parliament on July 23rd, 2023. This GO is broken down into several specific objectives:

SO1. To describe the evolution of the “Perro Sanxe” meme, from its initial criticism of the president of the government to its appropriation by the PSOE.

SO2. To analyze the online media coverage of the “Perro Sanxe” meme before, during and after the electoral campaign.

SO3. To describe the strategy developed by the PSOE communication department to humanize the candidate Pedro Sánchez Castejón through the humorous appropriation of the meme.

As the discursive strategy of the Popular Party, the main opposition party and favorite in most electoral polls (Rico, 2023), focused the axis of its campaign on ad hominem attack the socialist candidate under the maxim of “repealing ‘sanchismo’” (Gil, 2023), humanizing Pedro Sánchez became a central objective for the socialist party's campaign.

3. METHODOLOGY

This paper presents an exploratory-descriptive methodological design that adopts critical discourse analysis (hereafter, CDA) (Fairclough, 2006) to analyze and relate the discourse developed by the candidate through interviews in infotainment programs and the media discourse about the resignification of the meme. The CDA is approached because it is understood as the most appropriate approach to understand how a political party manages to resignify and appropriate a polyphonic public discourse such as the meme (Denisova, 2019) to integrate it into the electoral campaign strategy. The data was collected through the compilation and analysis of all the interventions of the PSOE candidate in infotainment programs on radio and television, as well as in new formats such as audiovisual podcasts, and in interviews of a purely informative nature. In total, 11 hours, 44 minutes and 32 seconds of interviews of the candidate in 16 programs were reviewed (Table 1).

Table 1. Interventions by Pedro Sánchez in pre-campaign and election campaign.

|

Program |

Media |

Date |

Duration |

|

[Audiovisual interview] |

El País |

06/16/2023 |

42:18 |

|

Más de Uno |

Onda Cero |

06/19/2023 |

53:18 |

|

El Intermedio |

La Sexta |

06/20/2023 |

47:27 |

|

Audiovisual interview |

InfoLibre |

06/24/2023 |

54:13 |

|

Hora 25 |

Cadena SER |

06/26/2023 |

49:28 |

|

El Hormiguero |

Antena 3 |

06/27/2023 |

53:12 |

|

AR |

Telecinco |

07/04/2023 |

01:07:00 |

|

Audiovisual interview |

ElDiario.es |

07/09/2023 |

48:55 |

|

Hora Veintipico |

Cadena SER |

07/12/2023 |

47:26 |

|

Hoy por Hoy |

Cadena SER |

07/13/2023 |

40:44 |

|

La Pija y la Quinqui |

Spotify |

07/15/2023 |

57:20 |

|

Las Mañanas |

RNE |

07/17/2023 |

31:43 |

|

Audiovisual interview |

Público |

07/20/2023 |

34:44 |

|

Al Rojo Vivo |

La Sexta |

07/20/2023 |

-[1] |

|

La Hora de la 1 |

TVE |

07/21/2023 |

31:19 |

|

Julia en la Onda |

Onda Cero |

07/21/2023 |

45:25 |

|

Total analyzed time |

11:44:32 |

||

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

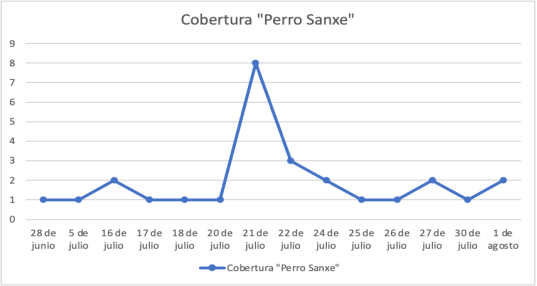

Likewise, secondary journalistic sources that covered the pre-campaign, campaign and post-campaign in the online environment were consulted in order to find out what story these media created by observing the transformation of the meaning of the meme and its use in the campaign. In total, 27 articles about “Perro Sanxe” were counted and consulted, from June 28, 2023 (the day after Pedro Sánchez was invited to El Hormiguero) to August 1, 2023.

Table 2. Coverage of “Perro Sanxe” in online editorials (by subject).

|

|

Subject |

Number of articles |

References |

|

Pre-campaign coverage |

Interview on El Hormiguero |

1 |

|

|

Story behind the meme |

1 |

Gómez Urzaiz, 2023 |

|

|

Campaign coverage |

Interviews in La Pija y la Quinqui |

4 |

|

|

Story behind the meme |

1 |

||

|

Meme on the ocassion of the International Dog Day |

8 |

Vicente, 2023; La Vanguardia, 2023; González-Madiedo, 2023; Tremending, 2023; H.A., 2023; Sobejano Agustín, 2023; |

|

|

Getting to know the PSOE strategy |

3 |

||

|

Post campaign coverage |

Story behind the meme |

1 |

La Opinión, 2023 |

|

Consolidation of the meme in the PSOE |

8 |

República, 2023; Diariocrítico, 2023; Merino, 2023; Sanz, 2023; Meseguer, 2023; Ventura, 2023; Guitián, 2023; Rubio Hancock, 2023 |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

In-depth interviews were also used in this research, which are presented as the best data collection technique when one wants to obtain proven knowledge from experts in a subject (Kvale, 2011). In this case, two people related to the campaign were interviewed: the director of communication of the PSOE, Ion Antolín Llorente, and the anonymous user of the account Mr. Handsome (@pdrsn). Handsome (@pdrsnche), a Pedro Sánchez fandom account on X, which currently has 81,700 followers.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Sanchismo and the demonization of the candidate

Pedro Sánchez began to offer a wide variety of interviews since June, both in news and infotainment programs. The analysis of these interviews allows the conclusion that one of the key points of the PSOE's argument for the general elections was to dismantle the negative connotations associated with the idea of sanchismo. In the audiovisual interview with El País on June 16, Pepa Bueno asks Sánchez “what is sanchismo?”, and he answers:

Sanchismo is the old strategy of the right wing when it is in opposition. It is to dehumanize, to depict, to caricature, to paint the progressive leader who is at the head of the Government as a selfish person, who thinks only of himself, who has no scruples whatsoever, and who does anything to stay in power. They did it with Felipe, calling socialism felipismo, they did it with José Luís calling socialism zapaterismo, and they do it with me calling socialism sanchismo. But sanchismo, felipismo, zapaterismo, is still socialism, and it is the main transforming force that this country has had, fortunately, during the last 40 years of democracy. (Sánchez, 2023a)

This argument is repeated in other interviews, such as in Más de uno (Onda Cero), where Sánchez affirms that saying Sanchismo is an attempt to dehumanize the political adversary. The candidate links the Popular Party with trumpism, a strategy that he defines as “questioning the electoral results” (Sánchez, 2023b), just as the PP did on May 28 talking about pucherazo by Sánchez. He also adds that Trumpism is based on the dehumanization of the candidate. In all the interviews analyzed -except for the podcast of La Pija y la Quinqui-, the Popular Party is directly related to the ultra-right. In Infolibre (June 24), Sánchez points out that the Popular Party is assuming the postulates of the ultra-right as its own; and one of these postulates is lying: “Trumpism means dehumanization and personal attack on the progressive leader who has the honor of leading the country” (Sánchez, 2023d). In fact, he insists that “more dangerous than VOX is a Partido Popular that assumes the postulates of VOX” (Sánchez, 2023c). For Sánchez, Feijóo “has been a great disappointment”, since “nobody expected this type of leadership based on lies, malice and manipulation” (Sánchez, 2023k).

At times, he refers to the fact that the right-wing media has presented him as “a seven-headed monster” (Sánchez, 2023d; Sánchez, 2023h). According to the candidate, the media mainly show conservative, manipulated points of view, “interested debates that seek to provoke fear among the citizenry, misinform and create hoaxes” (Sánchez, 2023d). Alluding to a famous phrase by Felipe González, Sánchez states that “public opinion is not the same as published opinion” (Sánchez, 2023f; Sánchez, 2023i).

[...] Published opinion does not correspond to public opinion. The sociology of our country is not 70% conservative. In some talk shows even 99% is conservative, it is hard to see a progressive. I believe that one thing is to explain what this strategy of Sanchismo has meant, which is nothing else but to muddy the field, the playing field to generate disaffection, to polarize the Spanish public opinion. And another is, well, to also communicate the proposals of the Spanish government. (Sánchez, 2023j)

On July 4, in AR, Sanchez again affirms that Sanchismo is “a bubble that has been inflated with manipulations, lies and also evil” (P. Sánchez interviewed in AR, 07/04/23). For the candidate, the media have crossed all red lines: “A president democratically elected at the ballot box in 2019 is told that he is a coup plotter. What's more, they go so far as to say the barbarity that I am a philoetarra; a philoetarra! Even more, it is said that I am a philoetarra; a philoetarra! Despite what terrorist violence has meant in our country during the last forty years” (Sánchez, 2023h).

It is within this discursive strategy of attack and caricaturization of the figure of Pedro Sánchez by the right wing where the meme of “Perro Sanxe” is initially located. Sanchez's feelings towards the meme during the pre-campaign can be observed in the Hora 25 interview:

Bretos: You, President, have personally suffered from knowing that they call you Perro Sanxe. That they refer to you in these terms, at this level of viscerality, has that made a dent on you personally?

Sánchez: Well, it is not pleasant, I can guarantee you that. I have tried, throughout these years as president of the government, not to lose my temper, not to lose my composure, to always remember that I am the president of the government and, therefore, I govern for everyone. (Sánchez, 2023e)

It is also interesting to highlight the words of the candidate in one of the last interviews of the campaign, the one given to Público on July 20:

[...] I throughout this campaign have also tried to prick this bubble that the conservative media and also the political and economic right wing have made over me about the action of my government and over me with this sanchismo, manipulation, lies and evil. The wickedness is found in this proclamation of “may txapote vote for you”. Txapote is serving a sentence as he deserves. It should be recalled that, after Miguel Ángel Blanco was murdered, with President Aznar as President of the Government and president of the Popular Party (by the way Abascal was then part of the Popular Party), he released and brought prisoners of ETA, and he did it weeks, months, after the murder of Miguel Ángel Blanco. The Popular Party and VOX are the only two parties that maintain that ETA exists, when ETA ceased to exist in 2011. Therefore, it is evil, it is manipulation, and it is lies. (Sánchez, 2023k)

Undoubtedly, the accusation to the right-wing media and the Popular Party for their use of lies against the coalition government and, especially, towards the figure of Sánchez, was one of the central axes of the PSOE's strategy. This type of accusation was not only observed repeatedly in the candidate's statements analyzed in this work, but also in the messages that the party disseminated in the pre-campaign in its official profiles under the title “La mentira”[2] (The lie), compiling episodes of past PP governments such as the management of the Prestige ecological disaster, the debate on the authorship of the 11M terrorist attacks in Atocha or “the Bárcenas papers” on the illegal financing of the party. This accusation would be taken up again in the last week of the campaign by the PSOE, after the electoral debate between Feijoó and Sánchez, where the socialist communication team focused on generating content that pointed to the lies of the popular candidate. As Ion Antolín Llorente explained in the interview:

[...] two minutes after leaving the debate, we were already talking about “well, this has not gone very well either, but we are not going to flagellate ourselves, we are going to win the post-debate”. What is the post-debate? this man has not told a single truth [...] this is when the communication machinery comes in... every day two videos, all the lies, but not offensive [videos], but in the sense of “I have caught you in a lie”, and I explain it; I make a fact-check and I explain it. (I. Antolín Llorente, personal interview, 10/19/23).

4.2. The usefulness of the meme in the humanization of the candidate

Given that the Popular Party focused the axis of its campaign on an ad hominem attack on the socialist candidate under the maxim of “repealing ‘sanchismo’”, humanizing Pedro Sánchez became one of the central objectives of the PSOE's campaign. In this sense, the “Perro Sanxe” meme helped to present the candidate as someone capable of laughing at himself, thus helping to deactivate the image of a distant and egomaniacal politician that seemed to have been established in public opinion. As Antolín Llorente pointed out in the in-depth interview:

![]() [...] he is a president who in one term of office has had to deal with the pandemic, the war in Ukraine... he has had to adopt a very institutional profile by obligation [...] and this may have given rise to an image of someone cold, someone calculating, which is true that he is not like that either, but well, sometimes politicians also wear armor... they are human, aren't they? (I. Antolín Llorente, personal interview, 10/19/23)

[...] he is a president who in one term of office has had to deal with the pandemic, the war in Ukraine... he has had to adopt a very institutional profile by obligation [...] and this may have given rise to an image of someone cold, someone calculating, which is true that he is not like that either, but well, sometimes politicians also wear armor... they are human, aren't they? (I. Antolín Llorente, personal interview, 10/19/23)

In order to show the person behind the politician as someone close and in whom the voter can recognize himself, the PSOE's strategy focused on achieving the maximum presence of the candidate in audiovisual formats and of long duration in the media (all the interviews analyzed exceeded 30 minutes):

[...] we need to have an impact on 20-25 million people, in a very short time and besides, it is not enough for me just the Telediario and the 20 seconds of the cut, we need them to listen to him for 10 minutes, because if they listen to him for 10 minutes they will see that he is not as they are painting him, that is, that he is a normal person, that you can ask him about everything, that he knows about indie music, that he has hobbies, that is, that he does not spend the day locked up in Moncloa. (I. Antolín Llorente, personal interview, 10/19/23)

The most appropriate format to show the person behind the politician is infotainment, especially audiovisual, since this type of program uses dialogue formats, where the politician can address the viewer through close-up shots and where there is usually a relaxed tone that lends itself to a relaxed chat about personal issues. In some, moreover, as in the podcast La Pija y la Quinqui (Peguer and Maturana, 2023), the set recreates a private space such as a kitchen, which helps to generate in the viewer the feeling of access to a more intimate moment, away from the scenarios and institutional environments. Sánchez's interviews in this type of programs during the electoral campaign were full of personal and family anecdotes of the candidate, very focused on transferring to the audiences his cultural tastes, a classic strategy of identity expression. This is something that can be seen in the following excerpt:

Maturana: What are you watching right now?

Sánchez: Now I'm watching a Spanish series, No me gusta conducir....(I don’t like to drive..)

Maturana: The one with Juan Diego Botto?

Sánchez: Yes, but for a very simple reason: I have a daughter who is getting her driver's license and we started watching it and I liked it, this thing about going to Cuenca to get her driver's license... well, I don't want to give you a spoiler... (Sánchez in Peguer and Maturana, 2023).

In the same vein, Sánchez recommended Spanish musician Bronquio on Hora Veintipico (Cadena SER), “I think he has a peculiar music that hooks me”, while sharing with the audience some anecdotes about daily life in the Moncloa Palace: “It's not easy for teenagers because you have security measures. If your daughters' friends have to visit you, they have to go through different and logical security controls. We try to make the floor where we live our home, we try to be like when we lived in our apartment” (Sánchez, 2023h).

Within the humanization strategy, the use of humor has proven to be a very useful resource, as explained by the creator of the account Mr. Handsome (@pdrsnche) when asked about the value of memes in political communication: “they are a way to get political content shared that often doesn't appear to be political, which makes them incredibly effective in creating opinion currents” (Mr. Handsome, personal interview, 10/19/23). The comment is of great interest as it indicates that the meme can affect the political positions of the subjects by avoiding psychological barriers such as disinterest towards party messages or, in general, towards political discourse. In this line, the creator of the account pointed out that the joke that works best among the followers:

[...] is the one about all the world leaders being in love with Pedro Sánchez, especially the relationship with Ursula von der Leyen. [...] The whole concept of “Mr. Handsome” is nothing but a joke that helps people to consume political content (speeches, interviews, etc.) with more interest and ease through humor and the humanization of the politician. (Mr. Handsome, personal interview, 10/19/23)

On the other hand, the “Perro Sanxe” meme helped to connect with the younger voter, as Antolín Llorente explained: “it works on a range of voters that interests us a lot, who do not vote a lot, and who may be receptive to any stimulus that is different, that does not go in the mainstream of any electoral campaign” (I. Antolín Llorente, personal interview, 10/19/23). In this sense, the PSOE's dircom pointed to the importance of having attracted this segment to explain the party's increase in votes with respect to 2019:

I believe that we have connected them with the elections in this way and, also, very important, we connected with them thanks to La Pija y La Quinqui[3] [...] we made daily trackings, and it was noticeable, you can see that there is a spike upwards which can only be explained because new voters come in. (I. Antolín Llorente, personal interview, 10/19/23)

In addition to the young segment, the meme was taken up by like-minded voters of all ages, who joined in its resignification as “[...] an outlet, to say ‘look, well now you eat it yourselves, because we go with pride, with our dogs everywhere’” (I. Antolín Llorente, personal interview, 10/19/23). This process was fueled by the party through the creation of videos that were posted on social media without a signature: “[...] you launched them and you were helped by the socialist youth communities [...] in the end this is a party that has capillarity [...] if you know how to use capillarity well, you don't need bots or resort to ugly things...” (I. Antolín Llorente, personal interview, 19/10/23).

4.3. The evolution of “Perro Sanxe”

Originally, the expression “Perro Sanxe” comes from a live in 2021, within a Telemadrid program, with a boy who, angry because they were going to close a ski slope in Navacerrada, said: “don't close it, Perro Sánchez, you are the worst” (Gómez Urzáiz, July 5, 2023). From then on, the nickname began to circulate among the Spanish right wing and was used as a disqualifier towards the president, something that, as noted above, was not pleasant for him. Two years later, just the day after the general elections were called, a 21-year-old student named Manuel Lardín, committed to the left and voter of the Sumar party (del Corral, July 27, 2023), created a meme with the image of a dog in a suit, which read “más sabe el perro sanxe por perro que por sanxe” (more the dog sanxe knows by dog than by sanxe). This student materialized the redefinition of the nickname by the Spanish young people, something of which they were already aware from the communication department of the PSOE: “We were already doing observation work, especially among very young people, as a result of the interrail and cultural youth vouchers”, says Ion Antolín, who noticed that the program of discounts for young people in transport was called in networks “the ‘Perro Sanxe’ youth voucher”, and deduced that “people between 18, 17, 20 or 24 years old were using it without a pejorative intention, that is, it was an affectionate and grateful appellative” (I. Antolín Llorente, personal interview, 10/19/23).

Thus, the party's communication team decided to make its own in the middle of the campaign, and then began to circulate anonymous memes, such as the one of a dog with a cape presented as “Perro Sánchez”; this was a success inside and outside the PSOE, as citizens soon asked for stickers of the dog (I. Antolín Llorente, personal interview, 10/19/23). Hence, from July 12 onwards, Pedro Sánchez was the one who mentioned the meme in his media interviews:

De Miguel: Many hoaxes have been spread about you, many things, many legends... You have been caricatured a lot. Is there one that has really made you laugh?

Sánchez: The “Perro Sanxe” thing, right?

Miguel: The “Perro Sanxe” thing is funny.

Sánchez: Yes, because in the end it has been twisted around and there are some memes that are quite good, quite funny... (Sánchez, 2023h).

Peguer: I had a right-wing boyfriend at the time and he said to me: “what a geek”. He'll have his reasons for changing his mind!

Sánchez: But, did he say Pedro Sánchez or “Perro Sanxe”? [All laugh]

Peguer: That's what we wanted to ask you too. Are you aware of “Perro Sanxe”?

Sánchez: I'm not very aware because I don't have time either, really. I try to be informed, but I'm not. But, well, the truth is that it is an experience that has been turned upside down.

Peguer: Of course, I was going to tell you, now people are fond of it.

Sánchez: There's a meme that I love....

Maturana: Is it the one about “más sabe el perro por Sanxe que por perro” (the dog is wiser for being Sanxe rather than for being a dog)?

Sánchez: No, for “being a dog rather than for being a Sanxe.” (Sánchez in Peguer and Maturana, 2023)

Otero: Well, if one enters the social media you find a lot of photographs of puppies, small and big dogs, it depends on the size, right? With a sign that says: vote. It doesn't say anything about the socialist party in many of them, but it already seems to be a sign. You have twist the “Perro Sánchez” thing around so that now you are even going to rely on pictures of dogs; I have even read somewhere that the latest slogan is “Pedro Sánchez is wiser for being a dog rather than for being a Sánchez )”

Sánchez: Yes, it's not Sanchez, it's Sanxe.

Otero: Yes, it's just that it's hard for me. Thank you for the correction.

Sánchez: But I didn't make that up, social media did....

Otero: And you have twisted it around. (Sánchez, 2023l)

As Antolín Llorente explained, “when he went to Julia [Otero], and to La Pija y La Quinqui, he already had an input that we were messing with this and that is why when they told him it was in a different tone, because it is true that we have passed him information” (I. Antolín Llorente, personal interview, 19/10/23). As the director of communication himself recalls, he asked the candidate: “it is an appellative, I say, forget the insult, get it out of your head, go out with this” (I. Antolín Llorente, personal interview, 19/10/23). Thus, quickly, “Perro Sanxe” was being used by the party workers themselves. In this sense, it is worth mentioning the creation of the “Perro Sanxe” game, disseminated by Juventudes Socialistas on July 14 (Juventudes Socialistas, 2023). Or the video viralized by Mr. Handsome on July 17, where the caped dog appeared fighting against a series of villains, identified with the following names: Ana Rosa, Pablo Motos, Alsina, Vicente Vallés, the right-wing media and Gish's gallop. The user indicated in the text “(...) I don't know who to thank for this (...)”, which can be analyzed as an example of political astroturfing (Kovic et al., 2018). Another peak moment of appropriation was the initiative of Pilar Alegría, current PSOE spokesperson, to upload a photo on Twitter of a dog with a PSOE bag on July 18, saying that “we all have a #PerroSanxe” (Figure 2). “You see that people start under their Twitter to post photos... well, of course, we join in,” says Antolín; “as soon as you see that this gets traction on its own then, from behind, you say ‘hey, upload photos, with a funny touch’” (I. Antolín Llorente, personal interview, 19/10/023). And this was the beginning of a user generated content campaign in social media in which PSOE voters uploaded photographs of their dogs with PSOE corporate elements, following the example of Alegría (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Evolution of the appropriation of the meme “Perro Sanxe” by the PSOE in the middle of the campaign.

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on X.

Figure 4. Photos of pets uploaded by X users.

Source: Elaborated by the authors and taken from X.

The photos of the pets were joined by other posts in support of the candidate. Most of these messages circulated on the X social network. Among these publications, the one by Rigoberta Bandini herself stands out, who viralized the moment when Pedro Sánchez proclaimed to be a fan of her in La Pija y la Quinqui (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Rigoberta Bandini's support for the socialist candidate after declaring himself a fan of the singer.

Source: Rigoberta Bandini [@rigobandini], 2023, July 16. https://x.com/rigobandini/status/1680924062095122433

The initiatives around the “Perro Sanxe” phenomenon went beyond X’s borders. On TikTok and Instagram there is an account called @perroxanche, which has 67 and 59 posts each. The first video was published on June 6 and the last one on July 22, 2023, which points to the fact that both were probably created for electoral purposes. Although interviewees make no mention of them, the lifespan of these accounts and the content of their videos are clear indications that this may be another example of political astroturfing (Kovic et al., 2018). In fact, in the July 22 video he literally says “vote dog” to stop the far-right. The content of both networks is usually the same and very focused on a young audience, gamer and interested in the furry[4] world.

The official appropriation of the meme by the Socialist Party took place at the Lugo rally on July 20. There, Pedro Sánchez entertained himself by greeting a dog in the audience, something that the PSOE of Galicia's Twitter account spread with the hashtag #PerroSanxe (Figure 5). The following day was the climax of the meme's officialization: it was the last day of the campaign, July 21, 2023, World Dog Day. So as to make an impact, an action was agreed with Moncloa:

![]() [...] the president is going to put a kind tweet with his dogs, ok; we are going to take out the meme that became so viral from the PSOE account, assuming that 'the “Perro Sanxe” is PSOE, we don't care if you treat it as an insult, because for us Pedro Sánchez is “Perro Sanxe” and he is wiser for being a dog rather than for being a sanxe. (I. Antolín Llorente, personal interview, 10/19/23)

[...] the president is going to put a kind tweet with his dogs, ok; we are going to take out the meme that became so viral from the PSOE account, assuming that 'the “Perro Sanxe” is PSOE, we don't care if you treat it as an insult, because for us Pedro Sánchez is “Perro Sanxe” and he is wiser for being a dog rather than for being a sanxe. (I. Antolín Llorente, personal interview, 10/19/23)

These two tweets (Figure 5) became “the most shared tweets of the campaign by far” (I. Antolín Llorente, personal interview, 10/19/23). To such an extent, that it was the PSOE campaign action with the most media coverage, as verified in the article count (figure 6). Hence, the communication direction of the PSOE chose to make some badges with “Perro Sanxe” and “Perra Sanxe” for the closing meeting of the campaign, which was that same day in Getafe (Figure 5). The demand for these badges was so high that it caused the PSOE web store to crash (I. Antolín Llorente, personal interview, 10/19/23).

Figure 5. Evolution of the appropriation of the meme “Perro Sanxe” by the PSOE at the end of the campaign.

Figure 5. Evolution of the appropriation of the meme “Perro Sanxe” by the PSOE at the end of the campaign.

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on X.

Figure 6. Coverage of “Perro Sanxe” in online editorials (per publication date).

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

In short, as Antolín Llorente explains about another original disqualifying nickname of the right, that of “Frankenstein government”, “there comes that point where you say ‘already with this, if tried to play it in favor, none of us is going to be bothered’; you have to look for the formula” (I. Antolín Llorente, personal interview, 10/19/23). And, finally, the press assumed the complete mimicry of the meme-candidate in post-electoral articles with headlines such as “Dear Perro Sanxe, appreciated Fakejóo” (El País), “The power of the dog; the dog Sanxe, of course” (La Voz de Galicia), “The power of the dog (sanxe)” (Diario de Ibiza), or “‘Perro Sanxe’ has won” (Voz Pópuli). As stated by the user of Mr. Handsome, this meme “proves that, if you know how to listen, you can use what people are talking about, in a spontaneous and non-directed way, to your advantage” (Mr. Handsome, personal interview, 10/19/23). This user had already used the expression in her account (dedicated to flattering Pedro Sánchez) in 2021: “It was something that people from the right used to attack while from the left it was used in more of a joking mode but (also as a way of laughing at that right), as I say, the positive redefinition was then something very, very [niche]” (Mr. Handsome, personal interview, 10/19/23). In the profile of Mr. Handsome in X it can be seen that the meme is mentioned several times. On June 26, the user publishes a tweet where she appeals to the affectionate use that Sánchez's followers make of what a priori was an insult. Similarly, on July 21, International Dog Day and the last day of the election campaign, Mr. Handsome alludes to his involvement in the redefinition of the meme since February 2021 (Figure 7).

Figure 7. The redefinition of the meme in the account of Mr. Handsome (@pdrsn). Handsome (@pdrsnche).

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on X.

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

As the results of the study show, the socialist party's strategy for the general elections of July 2023 was developed in a double discursive articulation that sought to improve the image of its candidate and to humanize him. In the first place, and from the first interviews during the pre-campaign, the candidate focused on developing a rational argumentation to refute the notion of “Sanchism” that had been installed in public opinion and its propagandistic use by the PP. In this sense, Sánchez argues in each and every one of the pre-campaign interviews and in the first ones of the campaign that “Sanchismo” comes from a manipulation strategy orchestrated by the right-wing media powers. It could be said that this would correspond to an old rule of war propaganda, that of “simplification and single enemy” (Domenach, 1986, p. 52-57). Sánchez thus takes the opportunity to link the Popular Party -his main opponent and favorite in the elections- with the ultra-right, specifically with Trumpism, a political strategy that includes the use of lies and manipulation. Thus, the PSOE's communication strategy focused on including in the public audience the message that Sánchez had been the object of a media persecution by the right and the Popular Party, thus seeking to generate the “underdog effect” (Simon, 1954), i.e., seeking to win the sympathy of the like-minded, especially those voters who understand that their party or candidate does not deserve an unfavorable result.

Secondly, and in parallel to this direct attack on the metaphor of Sanchismo through rational argumentation, the PSOE communication team was working on the redefinition of the “Perro Sanxe” meme and making it their own, thus betting on an emotional, humorous and ironic way of deactivating the negative image of its candidate. From this perspective, the meme contributed to the humanization of the candidate, presenting Sánchez as someone capable of laughing at himself. The commitment to participate in long audiovisual interviews allowed not only to deploy the socialist argument to the public opinion, but also to show the candidate as someone approachable and accessible. Likewise, participation in infotainment programs made it possible to communicate the more personal dimension of Sánchez, delving into the subdimension of privatization (Van Aelst et al., 2012), given that both the questions asked by the hosts of these programs and the initiative of the interviewee himself focused on issues of a personal nature. In this sense, the interview of Sánchez in the podcast La Pija y la Quinqui (Peguer and Maturana, 2023), which focused entirely on the candidate's personal experiences, is paradigmatic. It was this strategy and, especially, the participation in the podcast, which allowed Sánchez to connect with the youngest segment of the electorate, a group that, according to the PSOE's dircom, would probably have been abstentionist if they had not opted for this type of guerrilla communication actions, far from a traditional electoral campaign. The results coincide with the conclusions of Parmelee et al. (2022) regarding the appreciation of Generation Z for those politicians who are more accessible and tend to present themselves in their non-political role.

On the other hand, the wide coverage that the digital media and press headlines gave to this redefinition, as well as the continuous mention by Sánchez in campaign interviews and the publication of the “Perro Sanxe” meme in the official PSOE accounts, allowed a phenomenon that was initially niche to end up surpassing the young segment and the scope of social media, reaching a great deal of the electorate in the days leading up to the vote. Thus, the meme ended up being an essential propagandistic element in the campaign. The propagandistic potential of the meme, already studied by other authors (Burroughs, 2013; Moody-Ramirez and Church, 2019; Martínez-Rolán and Piñeiro-Otero, 2017; Meso-Ayerdi et al., 2017; Carrasco-Polaino et al., 2020; McLoughlin and Southern, 2021; Ruggeri, 2022), is also confirmed in the analyzed case, since it was key to the candidate's humanization strategy thanks to humorous approach and its viralization capacity. In this sense, it has been detected that the fact the PSOE made it its own is extremely similar to that developed by the Democratic Party of the “Dark Brandon” meme, initially critical of Biden, but redefined in his favor in the context of social media (Romano, 2023). The temporal coincidence in the development of both parties' strategies of redefinition of negative memes seems to point to an emerging trend in political communication that would respond to two advantages of appropriation. First, a meme that is already known has overcome the first challenge of these spaces: getting the attention of users, therefore, redefining it offers more guarantees of visibility and circulation of the message, since our brain recognizes the meme (Rodríguez, 2013). Secondly, and as it has been observed in the results of this work, the achievement of the redefinition favors the sense of pride and belonging on the part of those related to the candidate and the party, it produces a performative feeling, as if the achievement of this redefinition were a transcript of its capacity to change the electoral results.

Although the research design does not allow us to demonstrate what impact the meme generated on public opinion in terms of vote mobilization -beyond the opinions of the socialist campaign strategists consulted-, it can be affirmed its impact in terms of media presence and mobilization of supporters, who not only got involved in content creation campaigns around the meme, but also found in it a way to “let off steam”, a way to ironically vindicate a political figure they felt had been treated too harshly (underdog effect). Thus, the work points to the need to have a broad view from the research in political communication that allows understanding the way in which parties engage and appropriate phenomena characteristic of digital culture as a way to connect with younger voters, join the trends of the moment in these platforms, and connect emotionally with the groups of voters. In this sense, the conclusions point to the convenience of considering political fandom as an increasingly important stakeholder within political and electoral communication (Barnes, 2023; Caro-Castaño et al., 2024; Lee and Moon, 2021).

Finally, the results of the research raise some ethical dilemmas, such as the ease with which users and organizations, in this case the PSOE, can include messages on these platforms to generate or increase trends and emotional surges without assuming authorship of them, making the users of these platforms interpret them as opinions of the citizenry, in a clear example of political astroturfing (Kovic et al., 2018). The meme of Perro Sanxe turned into a superhero with a cape and disseminated in social media is an example of political astroturfing when it appears before the audience as a result of popular clamor and not as a product of the political party itself. Just like the aforementioned examples of the Perro Sanxe video game or the accounts that praise the meme on TikTok and Instagram and are used exclusively during election periods. These types of practices are integrated within the growing repertoire of disinformation and are especially problematic considering the ability of these platforms to disseminate what Illouz (2023) has called “imaginary affects”, the development of imagined narrative scripts around the enemy or the dangers of the nation, which arouse strong affective orientations and promote populism in a media environment that allows the distribution of specific information to hyper-segmented audiences.

6. REFERENCES

Adam, S. y Maier, M. (2010). Personalization of Politics A Critical Review and Agenda for Research. Annals of the International Communication Association, 34(1), 213-257. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2010.11679101

Antequera, J. (22 de julio de 2023). «Perro Sanxe», la campaña de la ultraderecha que termina dando votos al PSOE. Diario 16 Plus. https://acortar.link/ZbYliK

Asaín, I. y Ortiz, A. (22 de julio de 2023). 'Perro Sanxe' o cómo Sánchez usa la estrategia de Obama o Macri para que un ataque sea un lema. El Español. https://acortar.link/R6MjTc

Barnes, R. (2023). Fandom and Polarisation in Online Political Discussion: From Pop Culture to Politics. Palgrave Macmillan.

Bennett, W. L. (2012). The Personalization of Politics: Political Identity, Social Media, and Changing Patterns of Participation. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 644(1), 20-39. https://doi.org/10.1177/000271621245142

Burroughs, B. (2013). Obama trolling: Memes, salutes and an agonistic politics in the 2012 Presidential election. The Fibreculture Journal. Digital Media + Networks + Transdisciplinary Critique, 22, 258-76.

Campus, D. (2010). Mediatization and Personalization of Politics in Italy and France: The Cases of Berlusconi and Sarkozy. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 15(2), 219-235. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161209358762

Caro-Castaño, L., Marín-Dueñas, P.-P. y García-Osorio, J. (2024). La narrativa del político-influencer y su fandom. El caso de Isabel Díaz Ayuso y los ayusers en Instagram. Mediterránea, 15(1), 285-304. https://doi.org/10.14198/MEDCOM.25339

Carrasco Polaino, R., Villar Cirujano, E. y Tejedor Fuentes, L. (2018). Twitter como herramienta de comunicación política en el contexto del referéndum independentista catalán: asociaciones ciudadanas frente a instituciones públicas. Revista ICONO 14, 16(1), 64-85. https://doi.org/10.7195/ri14.v16i1.1134

Carrasco-Polaino, R., Sáchez-de-la-Nieta, M.- Ángel y Trelles-Villanueva, A. (2020). Las elecciones al parlamento andaluz de 2018 en Instagram: partidos políticos, periodismo profesional y memes. Revista Mediterránea de Comunicación, 11(1), 75-85. https://doi.org/10.14198/MEDCOM2020.11.1.19

Cué, C. E. (2023). Pedro Sánchez adelanta las elecciones generales al 23 de julio ante el fiasco de las autonómicas. ElPais.com. https://acortar.link/MGDiim

Davison, P. (2012). The language of memes. En M. Mandiberg (Ed.). The Social Media Reader (pp. 120–34). New York University Press.

Dean, J. (2017). Politicising fandom. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 19(2), 225-424. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148117701754

Del Corral, P. (2023). El creador del meme de “perro sanxe”: “No ponerle marca de agua ha sido la peor decisión de mi vida”. El Periódico de España. https://acortar.link/cvsltt

Denisova, A. (2019). Internet Memes and Society: Social, Cultural, and Political Contexts. Routledge.

Diariocritico (24 de julio de 2023). 'Perro Sanxe', protagoniza los memes del 23J. Madridiario. https://acortar.link/9ulAnA

Domenach, J-M (1986). Propaganda Política. Eudeba.

E. C. (2023). Pedro Sánchez comparte la foto definitiva para darle la vuelta a su mote de 'Perro Sanxe’. La Voz del Sur. https://acortar.link/2uR5bB

Fairclough, N. (2006). Discourse and social change. Polity Press.

Ferrero, J. F. (28 de junio 2023). «Más sabe Perro Sanxe por perro que por Sanxe». Reacciones a la entrevista de Sánchez en el Hormiguero. Spanish Revolution. https://acortar.link/TZnXVr

Filimonov, K., U. Russmann y J. Svensson (2016). Picturing the Party: Instagram and Party Campaigning in the 2014 Swedish Elections. Social Media + Society, 2(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116662179

García Aller, M. (22 de julio de 2023). Perro Sanxe y el fin del antisanchismo. El Confidencial. https://acortar.link/lSs5FR

Gil Orantos, B. (2023). “Derogar el ‘sanchismo'”: mismo objetivo, distintas vías para el PP y Vox. EFE. https://efe.com/espana/2023-06-16/derogar-sanchismo-pp-vox-objetivo/

Gómez Urzáiz, B. (2023). ‘Perrosanxe’: historia del meme que inventó un niño, alentó la derecha y se ha apropiado la izquierda. La Vanguardia. https://acortar.link/kfrWcp

Gordillo Rodríguez, M. T. y Bellido-Pérez, E. (2021). Politicians self-representation on instagram: the professional and the humanized candidate during 2019 Spanish elections. Observatorio (OBS*), 15(1), 109-136.

Guitián, J. (2023). El poder del perro; el perro Sanxe, claro. La Voz de Galicia. https://acortar.link/J1RjbX

Heraldo-de-Aragón (21 de julio de 2023). "Feliz día del perro": el PSOE y Pedro Sánchez bromean con el meme de "Perro Sanxe" en el último día de campaña. Heraldo. https://acortar.link/Y18dh0

Hernández-Santaolalla, V. y Rubio-Hernández, M. d. M. (2017). Fandom político en Twitter: La Cueva y los partidarios de Alberto Garzón en las elecciones generales españolas de 2015 y 2016. Profesional de la Información, 26(5), 838-849. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2017.sep.06

Illouz, E. (2023). La vida emocional del populismo. cómo el miedo, el asco, el resentimiento y el amor socavan la democracia. Katz Editores.

Juventudes Socialistas [@JSE_ORG] (14 de julio de 2023). ¿Qué el juego de Perro Sanxe no existe? El juego del imbatible Perro Sanxe apareció salvajemente [Post]. X. https://twitter.com/JSE_ORG/status/1679803671666741248

Kalkina, V. (2020). Between Humour and Public Commentary: Digital Re-appropriation of the Soviet Propaganda Posters as Internet Memes. Journal of Creative Communications, 15(2), 131-146. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973258619893780

Kovic, M., Rauchfleisch, A., Sele, M. y Caspar, C. (2018). Digital astroturfing in politics: Definition, typology, and countermeasures. Studies in Communication Sciences, 18(1), 69-85. https://doi.org/10.24434/j.scoms.2018.01.005

Kvale, S. (2011). Las entrevistas en investigación cualitativa. Morata.

La Opinión. (2023). El meme viral de 'perro sanxe' tiene su origen en Málaga. La Opinión de Málaga. https://acortar.link/Yc6jhQ

La Vanguardia (21 de julio de 2023). La divertida imagen de Pedro Sánchez para celebrar el Día Mundial del Perro: ''Te quiero, Perro Sanxe''. La Vanguardia. https://acortar.link/4lilPi

Lee, S. y Moon, W. K. (2021). New public segmentation for political public relations using political fandom: Understanding relationships between individual politicians and fans. Public Relations Review, 47(4). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2021.102084

López-Rabadán, P. y Doménech-Fabregat, H. (2018). Instagram y la espectacularización de las crisis políticas. Las 5W de la imagen digital en el proceso independentista de Cataluña. Profesional de la Información, 27(5), 1013-1029. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2018.sep.06

Martínez-Rolán, X. y Piñeiro-Otero, T. (2016). Los memes en el discurso de los partidos políticos en Twitter: análisis del Debate sobre el Estado de la Nación de 2015. Communication & Society, 29(1), 145-60. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.29.35935

Martínez-Rolán, X. y Piñeiro-Otero, T. (2017). El uso de los memes en la conversación política 2.0. Una aproximación a una movilización efímera. Prisma Social, 18, 56-84.

McAllister, I. (2007). The personalization of politics. En R. J. Dalton y H.‐D. Klingemann (Eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior (pp. 571-588). Oxford University Press.

McLaughlin, B. y Macafee, T. (2019). Becoming a Presidential Candidate: Social Media Following and Politician Identification. Mass Communication and Society, 22(5), 584-603. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2019.1614196

McLoughlin, L. y Southern, R. (2021). By any memes necessary? Small political acts, incidental exposure and memes during the 2017 UK general election. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 23(1), 60-84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148120930594

McSwiney, J., Vaughan, M., Heft, A. y Hoffman, M. (2021). Sharing the hate? Memes and transnationality in the far right’s digital visual culture. Information, Communication & Society, 24(16), 2502-2521. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2021.1961006

Menéndez, M. (2 de abril de 2023). Díaz lanza su candidatura sin “tutelas” y con la ausencia de Podemos: “Quiero ser la primera presidenta de mi país”. RTVE. https://acortar.link/mktjxa

Merino, O. (2023). Del mote Perro Sanxe a Rin Tin Tin. El Periódico. https://www.elperiodico.com/es/opinion/20230725/mote-perro-sanxe-rin-tin-90301155

Meseguer, V. (2023). 'Perro Sanxe' deroga el 'feijooísmo'. La Verdad. https://acortar.link/boL4cW

Meso-Ayerdi, K., Mendiguren-Galdospín, T. y Pérez Dasilva, J. (2017). Memes difundidos por usuarios de Twitter. Análisis de la jornada electoral del 26J de 2016. Profesional de la Información, 26(4), 672-83. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2017.jul.11

Moody-Ramirez, M. y Church, A. B. (2019). Analysis of Facebook meme groups used during the 2016 US presidential election. Social Media + Society, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118808799

Mucientes, E. (18 de julio 2023). Del Perro Sanxe al ¡Y lo sabes!, el "mastodóntico" archivo web de la Biblioteca Nacional que guarda todos los memes. El Mundo. https://www.elmundo.es/cultura/2023/07/18/64b5389dfc6c83ac588b459f.html

Nieland, J. U. (2008). Politainment. En W. Donsbach (Ed.). The International Encyclopedia of Communication. Blackwell Publishing. Blackwell Reference Online.

Oliver, P. (21 de julio de 2023). El PSOE felicita el Día Mundial del 'Perro Sanxe'. Diario de Mallorca. https://acortar.link/tJIyg5

Owen, J. (2019). Post-authenticity and the ironic truths of meme culture. En A. Bown, & D. Bristow (Eds.). Post memes: Seizing the memes of production (pp. 77-113). Punctum Books.

Parmelee, J. H., Perkins, S. C. y Beasley, B. (2022). Personalization of politicians on Instagram: what Generation Z wants to see in political posts. Information, Communication & Society, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2022.2027500

Peguer, C. y Maturana, M. (anfitriones) (15 de julio de 2023). Mr. Handsome con Pedro Sánchez (temporada 2, episodio 44) [podcast audiovisual]. En la Pija y la Quinqui. Spotify. https://open.spotify.com/episode/2EhcEwq6t8J8YNy6vUGYiC?si=870d2192048b4318

Pérez, P. (16 de julio de 2023). De 'Perro Sanxe' a 'Bizcochito': la peculiar entrevista de 'La Pija y la Quinqui' al presidente. El Comercio. https://acortar.link/8Q9DVB

Precedo, A. (17 de julio de 2023). Mr. Handsome, ‘perrosanxe’ y ‘la fashionaria’: así se reapropia la izquierda de los insultos de la derecha. infoLibre. https://acortar.link/Nk86i4

President Biden [@POTUS]. (2023, 30 de abril). Dark Brandon made an appearance at the White House Correspondents´Dinner [Post]. X. https://acortar.link/LE9dZJ

República. (24 de julio de 2023). Los perros y las perras de Sanxe. República. https://acortar.link/34GOla

Rico, J. (23 de julio de 2023). Sondeos de las elecciones generales de julio 2023: últimas encuestas. El Periódico. https://acortar.link/MGDiim

Rigoberta Bandini [@rigobandini]. (2023, 16 de julio). Perraaaa sanchez [Post]. X. https://x.com/rigobandini/status/1680924062095122433

Rodríguez, D. (2013). Memecracia. Los virales que nos gobiernan. Gestión 2000.

Romano, A. (2023). The “Dark Brandon” meme —and why the Biden campaign has embraced it— explained. Vox. https://acortar.link/h2VNyM

Rubio Hancock, J. (2023). Estimado Perro Sanxe, apreciado Fakejóo. El País. https://acortar.link/NtGQsN

Ruggeri, A. A. S. (2022). El uso del meme en las elecciones del 4-M: estudio de las estrategias argumentativas y de proyección de imagen de Isabel Ayuso como candidata y alcaldesa de Madrid. Cultura Latinoamericana, 35(1), 230-264.

Ruiz Anderson, R. (20 de julio de 2023). Perro Sánchez... ¿Cuál es el origen de este apodo? El Confidencial. https://acortar.link/58bXWx

Sánchez, P. (12 de julio de 2023i). Hora Veintipico #286 | Entrevista a Pedro Sánchez. Hora Veintipico (Cadena Ser). https://acortar.link/Bgs7hq

Sánchez, P. (13 de julio de 2023j). Pedro Sánchez: "Es una cortina de humo para que no se vean los pactos de la vergüenza". Hoy por Hoy (Cadena Ser). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_UsTvqNQwoA&ab_channel=HoyporHoy

Sánchez, P. (16 de junio de 2023a). Pedro Sánchez: “Mucho más peligroso que Vox es que el PP asuma sus políticas tras el 23J”. El País. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-li2jzUz0Xg

Sánchez, P. (19 de junio de 2023b). Alsina entrevista a Pedro Sánchez: “no es cierto que haya gobernado con Bildu”. Más de uno (Onda Cero). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WsNwoZOlUGU

Sánchez, P. (20 de julio de 2023k). Entrevista a Sánchez: "Podemos demostrar que somos capaces de parar el avance de la ultraderecha". Diario Público. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6YBBzzEid1Q&ab_channel=DiarioP%C3%BAblico

Sánchez, P. (20 de junio de 2023c). Entrevista en El Intermedio (temporada 17). El Intermedio (La Sexta). https://acortar.link/EzPvOX

Sánchez, P. (21 de julio de 2023l). Pedro Sánchez: "La vivienda tiene que ser la gran causa de la siguiente legislatura". Julia en la Onda (Onda Cero). https://acortar.link/GwKcTA

Sánchez, P. (24 de junio de 2023d). Sánchez: "Ha quedado claro que la derecha política y mediática me odia, pero ¿qué quiere para su país?”. infoLibre. https://acortar.link/mUeGci

Sánchez, P. (26 de junio de 2023e). Entrevista a Pedro Sánchez en Hora 25. Hora 25 (Cadena Ser). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yxaPfNUmNbY

Sánchez, P. (26 de junio de 2023f). Entrevista a Pedro Sánchez en Hora 25. Hora 25 (Cadena Ser) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yxaPfNUmNbY&ab_channel=Hora25

Sánchez, P. (4 de julio de 2023h). La entrevista íntegra a Pedro Sánchez, presidente del Gobierno, en ‘El programa de Ana Rosa’. El Programa de Ana Rosa (Telecinco). https://acortar.link/tEGOgM

Sanz, G. (2023). ‘Perro Sanxe’ ha ganado. Voz Pópuli. https://acortar.link/cTkoFv

Schultz, D. (2001). Celebrity Politics in a Postmodern Era: The Case of Jesse Ventura. Public Integrity, 3(4), 363-376. https://doi.org/10.1080/15580989.2001.11770886

Selva Ruiz, D. y Caro Castaño, L. (2017). Uso de Instagram como medio de comunicación política por parte de los diputados españoles: la estrategia de humanización en la ‘vieja’ y la ‘nueva’ política. Profesional de la Información, 26(5), 903-915. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2017.sep.12

Shifman, L. (2011). An anatomy of a YouTube meme. New Media & Society, 14(2), 187-203. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444811412160

Simon, H. A. (1954). Bandwagon and underdog effects and the possibility of election predictions. Public Opinion Quarterly, 18(3), 245-253. https://doi.org/10.1086/266513

Sobejano Agustín, D. R. (21 de julio de 2023). El ingenioso tuit de Pedro Sánchez que da la vuelta al meme de ‘perro sanxe’. El Plural. https://acortar.link/1uaX5r

Street, J. (2004). Celebrity Politicians: Popular Culture and Political Representation. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 6, 435-452. https://acortar.link/XYlLZH

Tang Serradell, M. H. (26 de diciembre de 2023). Spotify comparte su informe anual: Taylor Swift desbanca a Bad Bunny. Revista Young. https://acortar.link/9sjYHC

Tremending (2023). El troleo épico de Pedro Sánchez a sus 'haters': "Feliz día mundial del perro" (Sanxe). Público. https://acortar.link/dIwyui

Van Aelst, P., Sheafer, T. y Stanyer, J. (2012). The personalization of mediated political communication: A review of concepts, operationalizations and key findings. Journalism, 13(2), 203-220. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884911427802

Ventura, D. (2023). El poder del perro (sanxe). Diario de Ibiza. https://www.diariodeibiza.es/opinion/2023/07/30/perro-sanxe-90468227.html

Vicente, N. (21 de julio de 2023). El fenómeno "Perro Sanxe" llega a la cuenta de Twitter del PSOE. Onda Vasca. https://acortar.link/bHB6J4

Viejo, M. (16 de julio de 2023). ‘La Pija y la Quinqui’ y Pedro Sánchez o ‘perro sanxe’ a todas horas y en todas partes. El País. https://acortar.link/5oSj8M

Wiggins, B. E. (2019), The Discursive Power of Memes in Digital Culture: Ideology, Semiotics, and Intertextuality. Routledge.

Wood, M., Corbett, J. y Flinders, M. (2016). Just like us: Everyday celebrity politicians and the pursuit of popularity in an age of anti-politics. The British journal of politics and international relations, 18(3), 581-598. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148116632182

Woods, H. S. y Hahner, L. A. (2019). Make America meme again: The rhetoric of the Alt-Right. Peter Lang.

Zaera Bonfill, A., Tortajada Giménez, I. y Caballero Galvez, A. A. (2021). La reapropiación del insulto como resistencia queer en el universo digital: el caso Gaysper. Preciado. Revista de Investigaciones Feministas, 12(1), 103-113. https://doi.org/10.5209/infe.69684

Zolides, A. (2022). “Don’t Fauci My Florida:” Anti-Fauci Memes as Digital Anti-Intellectualism. Media and Communication, 10(4), 109-117. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v10i4.5588

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS, FUNDING AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors’ contributions:

Conceptualization: Barragán-Romero, Ana I. and Caro-Castaño, Lucía. Formal analysis: Barragán Romero, Ana I.; Caro-Castaño, Lucía and Bellido-Pérez, Elena. Data curation: Barragán Romero, Ana I.; Caro-Castaño, Lucía and Bellido-Pérez, Elena. Drafting-Preparation of the original draft: Barragán Romero, Ana I.; Caro-Castaño, Lucía and Bellido-Pérez, Elena. Drafting-Revision and Editing: Barragán Romero, Ana I. and Caro-Castaño, Lucía. Visualization: Bellido-Pérez, Elena. Supervision: Barragán Romero, Ana I.; Caro-Castaño, Lucía and Bellido-Pérez, Elena. Project management: Barragán Romero, Ana I. and Caro-Castaño, Lucía. All authors have read and accepted the published version of the manuscript: Barragán Romero, Ana I.; Caro-Castaño, Lucía and Bellido-Pérez, Elena.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

AUTHORS:

Ana I. Barragán Romero

University of Seville.

Associate Professor in the Department of Communication and Advertising at the University of Seville. PhD in Communication and Degree in Advertising and Public Relations and in Social and Cultural Anthropology. Her main line of research links the analysis of image, social networks and political propaganda. She has participated in numerous international conferences and published in prestigious journals.

Índice H: 5

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4285-9038

Scopus ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=49862682900

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=pfb1vhcAAAAJ

Lucía Caro-Castaño

University of Cadiz.

Professor in the Department of Marketing and Communication at the University of Cadiz, where she has been Coordinator of the Degree in Advertising and Public Relations and is currently Secretary of the Academic Committee in Cadiz of the Interuniversity Doctorate in Communication. She holds a PhD in Communication from the UCA and a degree in Advertising and Public Relations from the University of Seville, both degrees with an extraordinary award. Her lines of research focus on communication in social media platforms, especially in relation to social influence, political communication and new forms of public relations that allow these spaces.

Índice H: 10

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2720-1534

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=CfcdULwAAAAJ&hl=es

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Lucia-Caro-Castano

ScopusID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=57191170589

Publons: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/author/record/AFL-2376-2022

Academia.edu: https://uca-es.academia.edu/LuciaCaro

Dialnet: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/metricas/investigadores/2145677

Elena Bellido-Pérez

University of Seville.

PhD in Communication and Professor in the Department of Audiovisual Communication and Advertising at the University of Seville. She graduated in Advertising and Public Relations (Extraordinary End of Studies Award) and completed a master's degree in Communication and Culture. She received her PhD in 2020 with outstanding cum laude and International Mention from the University of Toronto; her dissertation “Propaganda, art and communication: theoretical proposal and model of analysis” also received the ATIC Research Award for the best doctoral dissertation and the Extraordinary Doctorate Award from the University of Seville. Elena has participated in international conferences and has published numerous articles and book chapters. Her pre-doctoral training was completed with stays in the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada.

Índice H: 10

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3107-5481

Scopus ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=57200677022

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=EcYO_A8AAAAJ&hl=es

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Elena-Bellido-Perez