Revista Latina de Comunicación Social. ISSN 1138-5820 / No. 83 1-21.

Differentiated politicization of discourses on Twitter in response to COVID-19: a comparison of local governments in Colombia

Politización diferenciada de discursos en Twitter ante la COVID-19: comparación de gobiernos locales en Colombia

María Idaly Barreto-Galeano

Catholic University of Colombia. Colombia.

Diana Rico-Revelo

University of the North. Colombia.

Andrea Velandia-Morales

Catholic University of Colombia. Colombia. University of Santiago de Compostela. Spain. andrea.velandia@usc.es

Catholic University of Colombia. Colombia.

Catholic University of Colombia. Colombia.

Juan Camilo Carvajal-Builes

Catholic University of Colombia. Colombia.

Alexis Carrillo-Ramírez

Catholic University of Colombia. Colombia. University of La Laguna. Spain

alu0101534640@ull.edu.es

José Manuel Sabucedo-Cameselle

University of Santiago de Compostela. Spain.

ABSTRACT

Introduction: When facing objective threatening situations such as the global pandemic caused by COVID-19, the messages of political leaders acquire a fundamental role in sustaining the social order and in the implementation of measures created to face the crisis. For this purpose, they construct differentiated discourses with emotional and ideological referents that legitimize government administration and configure a politicized collective identity. Therefore, this research analyzed the language used on Twitter (now X) of 18 mayors of the main cities of Colombia during the pandemic, with the objective of identifying frames of meaning of the threatening reality according to their political orientation (left-right). Methodology: Through a longitudinal non-experimental study, accounts were monitored for three weeks before and three weeks after the first officially registered case of COVID-19 in the country. Results: Right-wing mayors diffused mainly negative emotions to legitimize obedience; while left-wing mayors combined positive and negative emotions (anxiety and anger) to promote coping. Discussion: The findings reflect differentiated processes of collective identity that are politicized in the socio-political context of the health crisis. Conclusions: Further research on the instrumentalization of cognitive and emotional frames in the political context is recommended, given that they allow us to reveal communication strategies that influence public opinion as a frame of reference to overcome threatening situations at a global level. Also, the use of advanced data mining for the study of beliefs and emotions in real time that is communicated in digital media.

Keywords: political communication; twitter; discourse; COVID-19; politicized collective identity; digital social networks; ideological orientation.

RESUMEN

Introducción: Frente a situaciones objetivas de amenaza como la pandemia mundial ocasionada por la COVID-19, los mensajes de líderes políticos adquieren un papel fundamental en el sostenimiento del orden social y en la implementación de medidas para afrontar la crisis. Para ello, construyen discursos diferenciados con referentes emocionales e ideológicos que legitiman la gestión de gobierno y configuran una identidad colectiva politizada. Esta investigación analizó el lenguaje utilizado en Twitter (ahora X) de 18 alcaldes de ciudades de Colombia durante la pandemia, con el objetivo de identificar marcos de significado de la realidad amenazante según su orientación política (izquierda-derecha). Metodología: Mediante un estudio longitudinal no experimental, se monitorearon las cuentas durante tres semanas antes y tres después del primer caso de COVID-19 registrado oficialmente en el país. Resultados: Los alcaldes de derecha difundieron principalmente emociones negativas para legitimar la obediencia; mientras que los alcaldes de izquierda combinaron emociones positivas y negativas (ansiedad e ira) para promover el afrontamiento a la situación. Discusión: Los hallazgos reflejan procesos diferenciados de identidad colectiva que se politizan en el contexto sociopolítico de la crisis sanitaria. Conclusiones: Se recomienda continuar la investigación sobre la instrumentalización de marcos cognitivos y emocionales en el contexto político, dado que permite develar estrategias de comunicación que inciden en la opinión pública como marco de referencia para superar situaciones amenazantes a nivel global. Asimismo, el uso de minería de datos avanzada para el estudio de creencias y emociones en tiempo real que se comunica en medios digitales.

Palabras clave: comunicación política; twitter; discurso; COVID-19; identidad colectiva politizada; redes sociales digitales; orientación ideológica.

1. INTRODUCTION

In January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. Consequently, the Colombian government decreed a State of Emergency on March 17, 2020 and mandatory quarantine as of March 25, 2020 (Presidencia de la República, 2020). In this regard, the communications policy of the national government was questioned for generating a negative emotional atmosphere and monopolizing the media regarding the pandemic (Ramírez, 2021). This local, national and global political atmosphere led to a politicization of citizen behavior in the face of WHO recommendations focused on health protection and prevention of the spread of the outbreak (Ayuso y Pacho, 2021).

Particularly in Colombia, territorial governments (mayors' offices) proposed restrictive measures for public order, general security and health care. In the area of health care, the use of masks was made mandatory and care was encouraged through telemedicine and home medicine services. In education, students continued to learn at home. In transportation, mobility restrictions were decreed for some activities in the national territory. These measures limited the displacement of only one person per family for the acquisition of food, pharmaceutical, health and basic necessities products. In addition, the temporary closure of commercial establishments and the suspension of on-site jobs were ordered, except for essential sectors for health, food supply, cleaning and garbage collection, among others (Presidencia de la República, 2020).

The situation caused by COVID-19, catalogued as threatening at the individual and collective level (Garfin et al., 2020; Sabucedo et al., 2020; Urzúa et al., 2020), raised a public panorama that changed the interaction of the social system due to the modification and implementation of norms such as confinement or social isolation that would be unacceptable for people in a context without pandemic. It was also characterized by the overexposure of information in social networks of two types: (a) releases from official sources with scientifically supported data and (b) fake news that framed the pandemic as "a simple cold" or as a "conspiracy mode" (Buj, 2020; “OMS”, 2020).

In this context, this research developed a quantitative study on the messages disseminated on Twitter (now X) by local governors to address the threat of COVID-19 in Colombia. For this purpose, two observation periods are taken: the first, three weeks before the first case of COVID-19 in Colombia (March 6, 2020), and the second, three weeks after. It was proposed to compare frames of politicized collective identity according to the political orientation of the rulers. The results allow us to make several reflections, among which we highlight that: 1) the hashtags show a common agenda that positions COVID-19 as a threatening situation, 2) the mayors highlight common public agendas, 3) the emotional framing is carried out through a language that structures trends in the two moments analyzed, 4) a differentiated political framing is evidenced according to the partisan ideology of the mayors, 5) emotions are instrumentalized by political leaders to encourage certain attitudes of citizens in the face of global threats.

1.1. Framing theory

Although the media are a fundamental socialization agent to place specific topics on the public agenda and guide public opinion, as proposed in the agenda setting theory (Núñez-Gómez et al., 2020), multidisciplinary studies that allude to the role of other influential actors in the creation and dissemination of frames of meaning also stand out (Valera, 2016). In this line is located the framing theory, which "does not focus on the analysis of the topics chosen by the media, but on the way the information is presented to the audience, on the reasons for that choice and on the consequences that derive from it" (Ricart and Jordan, 2022, p. 651).

The framing process involves the selection of events from reality to define problems, diagnose causes or make moral judgments, making communication more attractive. Framing allows the construction of social reality by becoming a frame of reference or interpretation scheme for the population that attributes meanings to reality (Piñeiro-Naval y Mangana, 2018). As the framing is maintained in a coherent, durable and routine manner, the meaning of the world is structured and the information considered relevant to disseminate meanings is highlighted. This makes it possible to induce thoughts, feelings or decisions in the audience in a particular way, which are legitimized by the vision shared by others, and which generate a social norm from which the individual attributes meaning to aspects related to the framing (Ardèvol-Abreu, 2015; Piñeiro-Naval y Mangana, 2018).

In the face of crisis situations, a political opportunity is propitiated for the different groups disputing power to construct discourses that justify and legitimize a certain social order through messages of persuasion to public opinion (Sabucedo et al., 2017). In this way, political leaders can generate politicization dynamics through frames of meaning that incentivize support for certain policy measures. In the context of COVID-19, some rulers engaged in discursive struggles through their definition of the health crisis to legitimize the sociopolitical system and political-governmental actions through cognitive and emotional frames disseminated in the media (Barreto, 2020). Hence the importance of analyzing the framing processes transmitted by political leaders in the face of extraordinary events such as a pandemic, not only because government communication increased through digital social networks in the context of COVID-19 (Núñez-Gómez et al., 2020), but also because different politicization processes were evidenced during the crisis (Hamm, 2020).

Framing processes are made up of cognitive, emotional and behavioral orientations that offer alternative ways to understand reality, to evaluate it and to foster a certain disposition to action. For its analysis, the focus will be on the framing processes involved in the definition of a situation or delimitation of a problem, from which a collective identity is configured (Gamson, 1992; Goffman, 1974; Sabucedo et al., 2017) that, once politicized, can generate a mobilized collective identity (Sabucedo et al., 2010).

1.2. Framing and defining a situation

In order to define a situation, framing entails the delimitation of a diagnosis of a particular circumstance that is considered a problem by people who experience discomfort with it (Gómez, 2020). At the time of COVID-19, governments assumed different positions regarding the containment, propagation and mitigation measures proposed by the WHO. Countries that assumed the WHO measures opted for discourses focused on the need to stay at home, to restrict mobility and physical contact with others ("OPS", 2020), while leaders in "opposition" to the WHO measures encouraged the population to maintain daily life practices and to assume the "herd effect" model (Louwerse et al., 2021; Schmelza y Bowlesc, 2022). Empirical evidence also refers that the framing of the problem is context sensitive. In Colombia, for example, a study on political communication in a 15-month observation window (from January 2020 to March 2021) showed that the most mentioned words by political leaders in Twitter trills (now X) were: “COVID”, “coronavirus”, “vacuna”, “pandemia”, “toque”, “queda”, “seca”, “leyseca”, “toquedequeda”, “aislamiento”, “cuarentena” and “confinamiento” (Abadía et al., 2023). Consistently, an exploration of the content of the front pages of the main Spanish newspapers in COVID-19 identified that the categories most present were "health", "politics" and "economy" (Núñez-Gómez et al., 2020).

The definition of a situation as unfair also involves emotional dimensions that synergize with the cognitive component of the grievance. On Twitter (now X), the use of intergroup emotions and ideological bias is common in the political environment to propitiate outcomes (Renström y Back, 2021). In this digital environment, the emotional dimension of framing around grievance is usually associated with negative emotions. Thus, when faced with circumstances that generate outrage, people may experience what Gamson (1992) called hot cognition, as one of the components of injustice or grievance framing. This is hot cognition, in which anger or rage have a preponderant presence and can drive action to try to modify the conditions considered adverse (Shears y O'Dempsey, 2015). During the COVID-19 crisis, for example, the increase and visibility of social and economic inequality gaps generated and exacerbated feelings of anger and indignation (López-López y Velandia-Morales, 2020; Rodríguez-Bailón, 2020). However, it is worth highlighting that anger associated with an alternative action to deal with a crisis can interact with positive emotions such as hope (Erhardt et al., 2022).

Fear is also another negative emotion that traditionally emerges in contexts of adversity. During the pandemic, for example, the perception of risk and fear (van Bavel et al., 2020) grew as a response to a threatening social environment and manifested itself in the form of escape or need for protection. Another negative emotion that also emerges in the definition of grievance and can inhibit action is sadness in interrelation with feelings of helplessness, hopelessness and helplessness and other behaviors oriented to avoid action; it is also associated with losses or with the impossibility of pointing out a perpetrator of the harm (Losada et al., 2020). In the context of COVID-19, social interactions changed dramatically because social contact was limited and isolation from family and friends was indicated, raising levels of sadness (Sabucedo et al., 2020). In this regard, a comparative study among 18 countries on collective emotions during the COVID-19 outbreak showed that sadness is the emotion that increased the most in contrast to other negative emotions such as anger, which even decreased (Metzler et al., 2023).

Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted society in different emotional dimensions as a product of the sudden alteration of study, work, entertainment and sport routines, among other abrupt changes that generate frustration (López et al., 2020) and uncertainty about the future, which, in turn, increase anxiety (Moya and Willis, 2020). This negative emotion emerges in the face of concern and uncertainty about how to deal with the threat, as it increases in the first stage of a global pandemic and influences compliance with the measures imposed (Metzler et al., 2023).

1.3. Framing and shaping a politicized collective identity

The framing of collective identity starts from the "awareness that the situation of the group is not independent of the power relations that exist in a specific political context" (Sabucedo et al., 2010, p. 195). That is, around the framing of a situation as problematic and unjust, representations of an "us" that suffers the grievances associated with a situation defined as problematic are created. From this, senses of belonging to a shared category are elaborated that is prioritized in the diagnosis and that can be an ideology, group, gender or other (García-González y Bailey, 2019). In this sense, the identity framework recreates a shared vision of the world and of people situated in a particular era, while differentiating and interacting with other groups (Abrams et al., 2020).

In the current era, permeated by the use of digital social networks, collective identity is enlivened by cognitive orientations about ends, means and actions; also by virtual relationships and negotiations of meaning that support decisions, and emotional processes linked to senses of belonging (García-González y Bailey, 2019). In a paper on messages couched in terms of loyalty with appeals to community protection in the United States (Kaplan et al., 2023), for example, the efficacy of the messages in reducing anti-mask beliefs among conservative participants was demonstrated, compared to control messages delivering purely scientific information. Recent studies concur on the synergy between trust in the information conveyed about the pandemic and the adoption of protective behaviors (Sun et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2023). In this regard, it is emphasized that messages that echo core values of the receiver can be effective (Kaplan et al., 2023).

In turn, politicized collective identity allows the development of an awareness of the need for change and the possibility of influencing change in order to modify adverse conditions. The scope of politicized collective identity "should be reserved for the process by which subjects situate their collective identity in the political context and in competition with other collective identities" (Sabucedo et al., 2010, p. 195). Therefore, it is associated with the group's position in the political arena and shared beliefs about the capacity for agency (Sabucedo et al., 2010). In this order of ideas, during COVID-19, the situation was experienced by collectives that shared different sociopolitical contexts, whose leaders generated disputes about the management of the pandemic from political positions aligned with a partisan orientation (Dochow-Sondershaus, 2020). Therefore, the conditions and interactions of actors situated from diverse ideological positionings to confront the pandemic constituted a propitious scenario for the politicization of collective identities.

From this perspective, collective identity is politicized from the moment in which people "interpret the position of the endogroup and exogroups, and the relationships between them, taking into account this broader context" (Sabucedo et al., 2010, p. 194). In this sense, in the face of the COVID-19 threat, power relations according to political affiliation and ideological positioning gave rise to politicized collective identity processes (Fresno-Díaz et al., 2020). This relationship between the ideological spectrum and the different measures associated with justification has been extensively studied (Sterling et al., 2020). Left-wing ideology, for example, correlates to a greater extent with values such as universalism and benevolence; whereas a right-wing ideology prioritizes tradition, the need for security and power (Jost et al., 2016). In a research conducted in the United States on prevention behaviors and acceptance of health measures according to party affiliations (Republican-Democrats) and ideological positioning (conservative-liberal), the findings indicated considerable differences, since compared to Republicans, Democrats were more willing to adopt decrees on social distancing and hand-washing behaviors, also showing greater concern about the pandemic (Kushner et al., 2020).

This appraisal one makes of one's environment and the resources one possesses to cope with it is considered a collective, relational, and contextually situated process (Mackie y Smith, 2015). Therefore, collectivities of people who share a goal, but are not in physical proximity, can be understood in terms of group emotions (Zamudio et al., 2022). In this scenario, the messages of rulers can appeal to collective emotions and public agenda issues related to the defined problem to activate a politicized collective identity; not only because of the positioning of political leaders according to their ideological affiliations, but also because the politicized collective identity drives action (Zamudio et al., 2022). From political communication, these discourses are built on the basis of cognitive and emotional resources that make greater use of negative emotions such as fear, anxiety and sadness, because these emotions consolidate beliefs of insecurity, threat and stress (Mackie y Smith, 2015), and favor the acceptance of new social norms that would be unacceptable in a context that is not exceptional.

Taking into account the referents presented, the following hypotheses are put forward in this research:

H1. The framing carried out by the mayors during the situation experienced in the pandemic will change depending on the threatening situation. Therefore, in the face of the first case of COVID-19 in Colombia, negative emotions will increase and positive emotions will decrease. Thus, the political communication of the rulers after the first case will appeal more to the use of negative (vs. positive) emotions such as fear, anger and anxiety.

H2: The frames of meaning transmitted by the mayors before and after the first COVID-19 case in Colombia foster politicized collective identities according to the political orientation of the rulers. In this sense, the communication of ideologically left-wing rulers will appeal to an internal control of the situation (emotions of anger and anxiety for coping with the threat), while the political communication of ideologically right-wing rulers will be oriented to an external control of the situation (emotion of sadness and low internal control in the face of the threat situation).

2. OBJECTIVES

The pandemic caused a global political and communication crisis; in this regard, the messages of the rulers sought to maintain the stability and legitimacy of the social, political and economic system through speeches in line with their political positions on the left and right (Barreto, 2020); however, there are differences between the framing of regional leaders of each country and the central government, reflecting the politicization of the health crisis (Gollust et al., 2020). Not many papers have conducted research on changes in emotions before and after the emergence of COVID-19 (Ashokkumar and Pennebaker, 2021; Metzler et al., 2023). In this sense, the general objective of this study was to analyze the political communication from local governmental powers in Colombia, disseminated on their official Twitter accounts (now X) in two different moments of the health crisis (three weeks before the first case of COVID-19 in Colombia and three weeks after), to investigate frames of politicized collective identity around the management of COVID-19 according to the ideological orientation of political leaders.

The specific objectives were: (i) to know the cognitive categories transmitted in the messages of the mayors of Colombia to identify their presence in the configuration and reconfiguration of framing processes three weeks before and after the first case of COVID-19 at the national level; (ii) to know the emotional categories transmitted in the messages of the mayors of Colombia to identify their presence in the configuration and reconfiguration of framing processes three weeks before and three weeks after the first case of COVID-19 at the national level; (iii) to explore differences in the framing of the messages transmitted by the mayors of Colombia before and after the first COVID-19 case in Colombia, to identify processes of politicized collective identity according to the ideological dimensions that represent their party affiliation (left-right).

3. METHODOLOGY

This research, with a comparative descriptive design (Salkind, 2010), analyzes the cognitive and emotional frames that the mayors of Colombian cities transmitted in their communications. Two periods were compared: three weeks before and three weeks after the first case of COVID-19 in Colombia (March 6, 2020).

3.1. Data

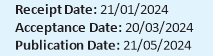

The official Twitter accounts (now X) of 18 mayors of capital cities in Colombia that used this social network during the study period were analyzed. Figure 1 shows the accounts and their coverage in the Colombian territory.

Figure 1: Official accounts of mayors analyzed on Twitter and capital city in charge.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

3.2. Procedure

The data download of the Twitter accounts (now X) was done with the Ncapture® tool, which were analyzed with the Nvivo® software to identify the most frequent tags (Hashtags: #) most frequent and plotted with the NodeXL® program. All tweets from the same week were grouped for analysis, so each account had six sampling points, three weeks before the first recorded case of COVID-19 (from February 12 to March 5, 2020) and three weeks after (from March 7 to March 27, 2020). In addition, emotional (Table 1) and cognitive (Table 2) linguistic variables were analyzed with LIWC® software version 2015 and the official Spanish dictionary (Ramírez-Esparza et al., 2007). A Wilcoxon test for related samples was also performed with SPSS® software, using the means of the measurements for each mayor.

Subsequently, a lexicometric analysis was performed with the SPAD7.2® software, executing a categorization of words based on emotions and following the methodology of statistical analysis of textual data (Bécue-Bertaut, 2010). Finally, this categorization led to an analysis of multiple correspondences between the identified linguistic variables and the mayoralties with R software, which were plotted with Python, so that their nodes were taken as coordinates in a factorial diagram.

Table 1. Emotional linguistic variables.

|

Variable |

Definition |

|

Positive emotions |

Words expressing emotions about rewarding experiences such as love, happiness, or gift (Pennebaker, 2011). |

|

Negative emotions |

Words that express emotions about unpleasant experiences related to anger, sadness, anxiety, and others (Pennebaker, 2011). |

|

Anxiety |

Words included in negative emotions associated with avoidance (Pennebaker, 2011). |

|

Anger |

Words included in negative emotions related to hatred, rage, revenge, and others (Pennebaker, 2011). |

|

Sadness |

Negative emotions expressing loss, failure or rejection (Pennebaker, 2011). |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Table 2. Cognitive linguistic variables.

|

Variable |

Definition |

|

Health |

Set of words expressing states of physical and mental health (Pennebaker et al., 2003). |

|

Achievement |

Words related to success and achievement (Pennebaker, 2011). |

|

Home |

Words related to places at home. For example, garden, living room, and others (Pennebaker, 2011). |

|

Family |

Words to refer to family members (Pennebaker, 2011). |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

3.3. Ethical considerations

The research was conducted under the privacy policy and terms of use of Twitter (now X). Tweets, hashtags, mentions and retweets are public information. The project was endorsed by the Research Ethics Committee of the Catholic University of Colombia.

4. RESULTS

To give context to the frames used by the mayors, an analysis of hashtags posted on the official Twitter accounts (now X) is presented below.

4.1. Assessment of the situation

The tags or hashtags show a common agenda oriented to mention the virus causing the threatening situation and to promote staying at home. The other tags show that the different mayors set issues to be highlighted in their public agendas. Figure 2 presents the top five tags with the highest frequency of appearance that were published in the official Twitter accounts (the gray spheres represent the 18 cities analyzed).

Additionally, the main labels show that the mayors tried to base their communications on contents that refer to the protection of human life, solidarity, tranquility, security, intelligence, obtaining and regulating economic resources, considering the economic recession produced by the lockdown. In addition to the cognitive framing communicated in the labels, an emotional framing is evident that is transmitted in the messages before and after the first case of COVID-19 in Colombia.

Figure 2: Main tags of the mayors' Twitter accounts.

Source: Created by the authors using NodeXL software.

In more detail, the cognitive and emotional linguistic variables were analyzed with LIWC® software and the results show differences in cognitive and emotional framing. The category most used by the mayors during the study period was achievement, but the use of words associated with this category decreased significantly after the first case of COVID-19 in Colombia (Z = -2.79; p = .005). The second most used category was related to positive emotions, which also decreased significantly after the first case of COVID-19 (Z = -3.46; p = .001). Other categories included in this study showed a lower percentage of use, although some also indicated significant changes (see Table 3). The use of words associated with the categories health, home, family, and negative emotions increased after the first instance of COVID-19 (Z = -3.26; p = .001; Z = -3.15; p = .002; Z = -2.50; p = .012; Z = -3.31; p = .001; respectively). When analyzing the three subcategories that make up the negative emotions category, only sadness increased (Z = -2.59; p = .010) while anger and anxiety did not reflect significant changes (Table 3).

Table 3. Descriptive data and Wilcoxon test.

|

Variable |

Before |

After |

Z |

||

|

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

||

|

Positive emotions |

3.94 |

1.16 |

2.68 |

.94 |

3.46 * |

|

Negative emotions |

.61 |

.46 |

.93 |

.46 |

-3.31 * |

|

Anxiety |

.10 |

.12 |

.12 |

.09 |

-1.09 |

|

Anger |

.34 |

.38 |

.42 |

.41 |

-1.32 |

|

Sadness |

.07 |

.07 |

.22 |

.16 |

-2.59 * |

|

Health |

.41 |

.28 |

.86 |

.32 |

-3.26 * |

|

Achievement |

4.18 |

.97 |

3.38 |

.61 |

-2.79 * |

|

Home |

.39 |

.62 |

.67 |

.22 |

-3.15 * |

|

Family |

.40 |

.62 |

.55 |

.61 |

-2.50 * |

Note *p < .05

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

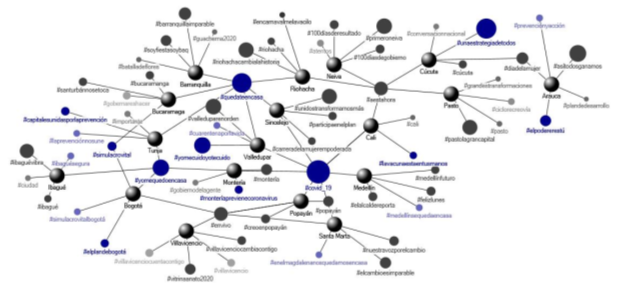

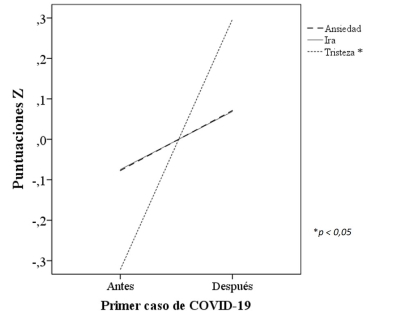

The comparison of cognitive and emotional frameworks before the first case of COVID-19 and three weeks later shows that negative and positive emotions are present in the two compared moments; however, after the first case of COVID-19, negative emotions increased, and positive emotions decreased. Likewise, these two dimensions did not present correlations in the first measurement, but they did in the second (r = .024, p < .001), that is, there are synergies between negative and positive emotions during the first case detected in Colombia (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Comparison of positive and negative emotions.

Source: Created by the authors using SPSS software.

Figure 4: Comparison of categories belonging to negative emotions.

Source: Created by the authors using SPSS software.

The results reflect those three weeks after the first officially detected case of COVID-19, sadness was the only emotion that increased significantly (Figure 4). In addition, all three emotions correlated significantly on the first measurement, with the correlation between anxiety and anger being highest (r = 36, p < .001); but on the second measurement only anger correlated significantly with anxiety (r = 39, p < .001).

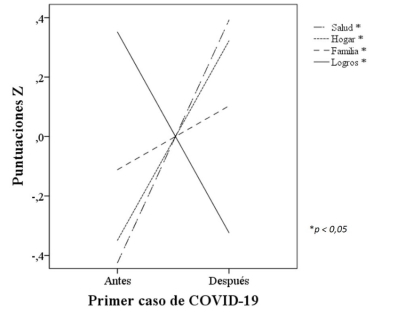

The results show that all words changed significantly three weeks after the first case. Health, home, and family increased while achievement decreased (Figure 5). During the first measurement, all words presented a significant correlation, but in the second measurement the words that correlated significantly were home with achievement (r = 33, p < .05) and home with health (r = 33, p < .05).

Figure 5: Comparison of categories associated with personal concerns.

Source: Created by the authors using SPSS software.

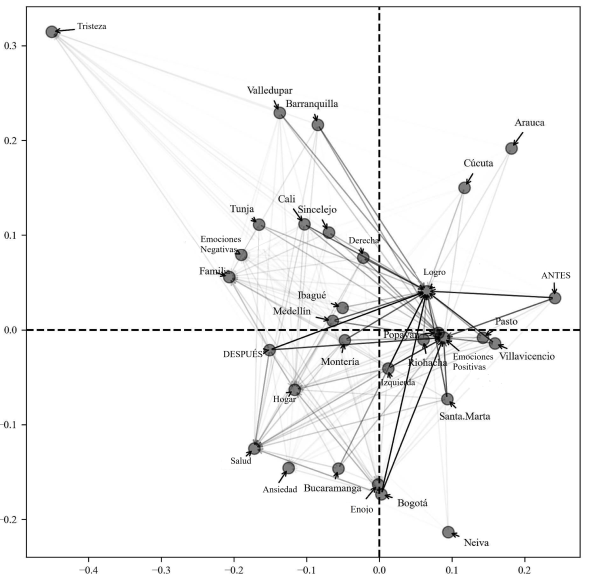

4.2. Politicization

The factorial diagram (Figure 6) allows us to observe the associations between mayors according to their emotional and cognitive frameworks and ideological positions. The first factor, located on the X-axis, is labeled: Vulnerability-oriented communication - achievement-based framing and protection from threat (obedience-oriented political consciousness). It is characterized by linguistic categories that frame the situation before the first instance from the achievement perspective and focuses the argumentation on the family combined with negative emotions, in general, and sadness, in particular. However, after the first case of COVID-19, the rulers include anxiety to legitimize health measures to protect against the virus and extend the cognitive framing to the household and the health domain. This content assumes a situation of helplessness and promotes the need for protection (external control) which is linked to parties that have a vocabulary close to conservative positions (right wing).

The second factor, located on the Y-axis, is labeled: Threat-oriented communication - framing based on coping with threat (coping-oriented political awareness). It is characterized by linguistic categories that frame the situation before the first instance from achievement combined with positive emotions in general. However, after the first case of COVID-19 they reorient the framing to home and health, along with anxiety and anger; this interaction encourages action to cope with the threat and promotes internal control characteristic of parties that have a vocabulary close to progressive (left) standpoints. In this sense, prior to the detection of the first COVID-19 case, the meaning frames associated with coping with the pandemic are permeated by positive emotions and, subsequently, positive emotions interact with anxiety and anger, encouraging action in the midst of adversity.

Figure 6: Map of relations between mayors according to ideological positions and frameworks.

Source: Elaborated by the authors with Python.

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The results allow us to deepen in approaches that support the hypotheses and suggest contributions to continue some lines of research. Regarding the first hypothesis, it is confirmed that negative emotional frameworks increase in threatening environments; however, synergies between negative and positive emotions are evidenced that can lead to behaviors similar to those framed by the rulers. In this sense, three reflections of these findings are raised with respect to the first hypothesis. The first is that when faced with an event considered dangerous, negative emotions are triggered (Shears y O'Dempsey, 2015), which favor the acceptance of social norms and rules that would be intolerable in non-threatening environments, but which in conditions such as those derived from COVID-19 provide certainty and social security. Specifically, it was found that anxiety and anger persisted in the two moments analyzed with significant correlations. This is consistent with the fact that during the second measurement, three weeks after the first officially detected case in Colombia, the national government declared a state of emergency on March 17 and decreed a mandatory quarantine on March 25, 2020. Therefore, citizens experienced shared national measures to face the threat, accompanied by daily broadcasts of the president of the republic with public health experts to explain and legitimize the measures. Hence, fear was not present in this framing process because the central government proposed measures based on technical information, unlike studies conducted months before the declaration of the State of Emergency, in which fear was a predominant emotion (Abadía et al., 2023).

The second consideration is based on the increase in sadness after the first case detected. This coincides with recent studies (Ashokkumar y Pennebaker, 2021; Metzler et al., 2023) and is important because sadness fosters feelings of defenselessness, hopelessness and helplessness; and it is related to avoidance and the request for help (Losada et al., 2020). In this sense, it is relevant that mayors with right-wing party affiliation encouraged sadness in their messages in the two moments analyzed. This is because such emotion facilitates the acceptance of the norms imposed by the national government of the time, which also had a right-wing party affiliation.

The third insight is that, despite the significant increase in negative emotions during the second measurement, positive emotions are still present and positively correlated with negative emotions. Mayors with left-wing party affiliation spread positive emotions before and after the first detected case, which synergized with anxiety and anger to encourage perceived agency and self-control as a route to deal with the pandemic. From this perspective, the responsibility of the framing made by the governors on global threat situations is emphasized, since they guide parameters to assess the situation and, consequently, to assume passive or proactive behaviors.

In relation to the second hypothesis, it was found that the discourse used on Twitter (now X) by the mayors maintains an alignment with their ideological position. In this regard, two reflections arise. The first is that the mayors' offices located in the right-wing political spectrum (vs. left) framed a communication oriented to vulnerability, emphasizing the category of "family", and disseminated sadness as an emotional resource. This shows an orientation towards external control and State protectionism in the face of threat: "the State protects me". On the other hand, rulers with a left-wing ideology (vs. right-wing) focused their communication on the awareness of the threat through the category of "health" and the transmission of emotions that allow them to face it, such as anger and anxiety. Thus, a strategy of internal control and coping with the threat is evident. These findings account for how a threatening situation derived from COVID-19 has politicized the health crisis (Gollust et al., 2020). In this sense, emotional management and ideological alignment in communications acquire high relevance in their social implications, such as propitiating behaviors of defenselessness from avoidance, or protection from the appropriation of certain measures.

The second insight is that the differentiated dynamics in the frameworks of meaning elaborated by right-wing and left-wing rulers reflect processes of politicized collective identity with different frameworks. Although the macro context of the pandemic delimited a common external threat (the contagion of the virus), the mayors of the 18 cities included in the study elaborated frameworks of meaning and interpretation (passivity versus action) according to the ideological spectrum to which they belonged. The language of mayors with right-wing ideology promoted a framework of interpretation to face the threat from protection, envisioning an "obedient collective identity that assumes a determined status-quo" (Sabucedo et al., 2010, p. 194); while mayors with left-wing ideology elaborated framing processes that propose "alternatives and exits for the group" (Sabucedo et al., 2010, p. 194). Likewise, the role of anger and anxiety in the mayors' framings is highlighted, although in a differentiated manner, because these emotions enliven the awareness of action, in contrast to fear, which tends to promote inhibition (Renström y Back, 2021).

The results of this work allow us to recommend future studies on the instrumentalization of emotions by political leaders to propitiate certain responses to global threats according to partisan ideological affiliation. Finally, it should be noted that this research contributes empirical evidence to two contemporary lines of study: one associated with the politicization of the pandemic in Latin America in comparative perspective (left-right) at intra-national, international and transnational levels; the other contributes to the validity of the dictionary used in real time and in the face of a historical event such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, among the limitations of the study, it should be noted that a social network other than Twitter (now X) was not used. Additionally, the analysis focused on emotions and cognitions in a political context, given that it is not possible with this methodology to analyze genres or figures such as irony and satire (Gutiérrez-Rubi, 2023).

6. REFERENCES

Abadía, A., Manfredi, L. y Sayago, J. (2023). Comunicación de crisis durante la pandemia del COVID-19 y su impacto en los sentimientos de la ciudadanía. Opinión Pública, 29(1), 199-225. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-01912023291199

Abrams, D., Travaglino, G., Grant, P., Templeton, A., Bennett, M. y Lalot, F. (2020). Mobilizing IDEAS in the Scottish Referendum: Predicting voting intention and well-being with the Identity-Deprivation-Efficacy-Action-Subjective well-being model. British Journal of Social Psychology, 59, 425-446. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12355

Ardèvol-Abreu, A. (2015). Framing o teoría del encuadre en comunicación. Orígenes, desarrollo y panorama actual en España. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 70, 423-450. https://acortar.link/YwycAB

Ashokkumar, A. y Pennebaker, J. W. (2021). The Social and Psychological Changes of the First Months of COVID-19. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/a34qp

Ayuso, S. y Pacho, L. (2021, julio 25). Las protestas por las restricciones para contener la pandemia se extienden por el mundo. El País. https://acortar.link/XuQLcA

Barreto, I. (2020). La doble amenaza emocional en la pandemia del COVID-19. En N. Molina (Ed.). Psicología en contextos de COVID-19, desafíos poscuarentena en Colombia (pp. 157-167). ASCOFAPSI. https://ascofapsi.org.co/pdf/Libros/Psicologia-contextos-COVID-19_web%20(1).pdf

Bécue-Bertaut, M. (2010). Minería de textos: Aplicación a preguntas abiertas en encuestas. Editorial La Muralla.

Erhardt, J., Freitag, M. y Filsinger, M. (2022). Leaving democracy? Pandemic threat, emotional accounts and regime support in comparative perspective. West european politics, 46(3), 477-499. https://acortar.link/wy1pob

Buj, A. (2020). La COVID-19 y las viejas epidemias. No es la tercera guerra mundial, es el capitalismo. Ara@ne: Revista electrónica de recursos en internet sobre geografía y ciencias sociales, 24(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1344/ara2020.242.31379

Dochow-Sondershaus, S. (2020). Ideological polarization during a pandemic: Tracking the alignment of attitudes toward COVID containment policies and left-right self-identification. Frontiers in Sociology, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2022.958672

Fresno-Díaz, A., Estevan-Reina, L., Sánchez-Rodríguez, A., Willis, G. y de Lemus, S. (2020). Fighting inequalities in times of pandemic: The role of politicized identities and interdependent self-construal in coping with economic threat. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 33, 436-453. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2632

García-González, L. y Bailey, G. (2019). La identidad colectiva en línea en los movimientos sociales por la paz en México. Aproximación crítica desde un análisis en Comunicación y Cultura Digital (2011-2013). Virtualis, 10(18), 16-39. https://www.revistavirtualis.mx/index.php/virtualis/article/view/266/297#toc

Gamson, W. (1992). Talking politics. Cambridge University.

Garfin, D., Silver, R. y Holman, E. (2020). The Novel Coronavirus (COVID-2019) Outbreak: Amplification of Public Health Consequences by Media Exposure. Health Psychology Journal (Advance online publication). https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000875

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame Analysis. Harvard University Press.

Gollust, S., Nagler, R. y Franklin, S. (2020). The Emergence of COVID-19 in the US: A Public Health and Political Communication Crisis. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 45(6), 967-981 https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-8641506

Gómez, M. (2020). La astucia de la sinrazón. Pasado y presente de los frames de la derecha movimientista. Cartografías del sur, 12, 286-315.

Gutiérrez-Rubi, A. (2023). Gestionar las emociones políticas. Editorial Gedisa. https://www.gedisa.com/gacetillas/891050.pdf

Hamm, M. (2020). Physically Distant – Socially Intimate: Reflecting on Public Performances of Resistance in a Pandemic Situation. Anthropology in Action, 27(3), 56-60. https://doi.org/10.3167/aia.2020.270312

Jost, J., Basevich, E., Dickson, E. y Noorbaloochi, S. (2016). The place of values in a world of politics: Personality, motivation, and ideology. En T. Brosch y D. Sander (Eds.). Handbook of value: Perspectives from economics, neuroscience, philosophy, psychology, and sociology (pp. 351-374). Oxford University Press.

Kaplan, J., Vaccaro, A., Henning, M. y Christov‑Moore, L. (2023). Moral reframing of messages about mask‑wearing during the COVID‑19 pandemic. Scientifc Reports, 13. https://acortar.link/umkxuz

Kushner, S., Wallace, S. y T. Pepinsky. (2021). Partisanship, Health Behavior, and Policy Attitudes in the Early Stages of the COVID-19 Pandemic. PLOS ONE, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249596

López, J., Duarte, L., y Morad, J. (2020). COVID-19 and labour law: Colombia. Italian Labour Law e-Journal 3, 1-4. https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.1561-8048/10777

López-López, W. y Velandia-Morales, A. (2020). Pandemia y aislamiento en tiempos de desigualdad: las banderas rojas de la cuarentena. Interamerican Society of Psychology Bulletin. Special Issue COVID-19, 33-36.

Losada, J., Rodríguez, L. y Paniagua, D. (2020). Comunicación gubernamental y emociones en la crisis del Covid-19 en España. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 78, 1-18. https://acortar.link/JVXzda

Louwerse, T., Sieberer, U., Tuttnauer, O. y Andewega, R. (2021). Opposition in times of crisis: COVID-19 in parliamentary debates. West European Politics, 44, 1025-1051. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2021.1886519

Mackie, D. y Smith E. (2015). Intergroup emotions. En M. Mikulincer, P. R. Shaver, J. F. Dovidio y J. A. Simpson (Eds.). APA Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology (Vol. 2) (pp. 263-293). Group Processes. American Psychological Association.

Metzler, H., Rimé, B., Pellert, M., Niederkrotenthaler, T., Di Natale, A. y García, D. (2023). Collective emotions during the COVID-19 outbreak. Emotion, 23(3), 844-858. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0001111

Moya, M. y Willis, G. (2020). La Psicología Social ante la Pandemia del COVID-19. International Journal of Social Psychology, 35(3), 590-599. https://doi.org.10.1080/02134748.2020.1786792

Núñez-Gómez, P., Abuín-Vences, N., Sierra-Sánchez, J. y Mañas-Viniegra, L. (2020). El enfoque de la prensa española durante la crisis del Covid-19. Un análisis del framing a través de las portadas de los principales diarios de tirada nacional. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 78, 41-63. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2020-1468

OPS. (2020). Reporte de Situacion COVID-19 Colombia. OPS. https://acortar.link/G7wTeU

Pennebaker, J. W. (2011). The secret life of pronouns: What our words say about us. Bloomsbury Press/Bloomsbury Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0262-4079(11)62167-2

Pennebaker, J. W., Mehl, M. R. y Niederhoffer, K. G. (2003). Psychological aspects of natural language use: Our words, our selves. Annual Review of Psychology, 54(1), 547-57. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145041

Piñeiro-Naval, V. y Mangana, R. (2018). Teoría del Encuadre: panorámica conceptual y estado del arte en el contexto hispano. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 24(2), 1541-1557. https://doi.org/10.5209/ESMP.62233

Presidencia de la República. (2020, marzo 23). Gobierno Nacional expide el Decreto 457, mediante el cual se imparten instrucciones para el cumplimiento del Aislamiento Preventivo Obligatorio de 19 días en todo el territorio colombiano. https://acortar.link/Uq8F09

Ramírez, J. (2021). Crisis del coronavirus: comunicación gubernamental en la presidencia de Iván Duque. [Tesis de grado]. Universidad Javeriana. https://acortar.link/9zgVxj

Ramírez-Esparza, N., Pennebaker, J., García, F. y Suriá, R. (2007). La psicología del uso de las palabras: Un programa de computadora que analiza textos en español. Revista Mexicana de Psicología, 24(1), 85-99.

Renström, E. y Back, H. (2021). Emotions during the COVID-19 pandemic: Fear, anxiety, and anger as mediators between threats and policy support and political actions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 51, 861-877. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12806

Ricart, A. y Jordan, M. (2022). Análisis contrastivo de los encuadres culturales de noticias sobre COVID-19 en The Guardian y El País basado en el uso de sustantivos. Revista Científica de Información y Comunicación, 19, 647-673. https://dx.doi.org/10.12795/IC.2022.I19.28

Rodríguez-Bailón, R. (2020). La desigualdad ante el espejo del COVID-19. Monográfico del International Journal of Social Psychology, 61-71. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/fdn32

Sabucedo, J. M., Durán, M. y Alzate, M. (2010). Identidad colectiva movilizada. Revista de Psicología Social, 25(2), 189-202 https://doi.org/10.1174/021347410791063822

Sabucedo, J. M., Barreto, I., Seoane, G., Alzate, M., Gómez-Román, C. y Vilas, X. (2017). Political protest in times of crisis. Construction of new frames of diagnosis and emotional climate. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(1568). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01568

Sabucedo, J. M., Alzate, M. y Hur, D. (2020). El COVID-19 y la metáfora de guerra. International Journal of Social Psychology, 35(3), 618-624. http/doi.org/10.1080/02134748.2020.1783840

Salkind, N. (2010). Encyclopedia of research design. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412961288

Schmelza, K. y Bowlesc, S. (2022). Opposition to voluntary and mandated COVID-19 vaccination as a dynamic process: Evidence and policy implications of changing beliefs. PNAS, 119(13), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2118721119

Shears, P. y O’Dempsey, T. (2015). Ebola virus disease in Africa: epidemiology and nosocomial transmission. Journal of Hospital Infection, 90(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2015.01.002

Sterling, J., Jost, J. y Bonneau, R. (2020). Political psycholinguistics: A comprehensive analysis of the language habits of liberal and conservative social media users. Journal of personality and social psychology, 118(4), 805-834. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000275

Sun, Y., Hu, Q., Grossman, S. y Basnyat, I. (2021). Comparison of COVID-19 Information Seeking, Trust of Information Sources, and Protective Behaviors in China and the US.

Journal of Health Communication, 26(9), 657-666. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2021.1987590

Urzúa, A., Vera-Villarroel, P., Caqueo-Urízar, A. y Polanco-Carrasco, R. (2020). La Psicología en la prevención y manejo del COVID-19. Aportes desde la evidencia inicial. Terapia Psicológica, 38(1), 103-118.

Valera, L. (2016). El sesgo mediocéntrico del framing en España: una revisión crítica de la aplicación de la teoría del encuadre en los estudios de comunicación. Zer, 21(41), 13-31. https://doi.org/10.1387/zer.16404

van Bavel, J., Boggio, P., Capraro, V., Cichocka, A., Cikara, M., Crockett, M., ... Ellemers, N. (2020). Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nature Human Behaviour, 4, 460-471. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-020-0884-z

Wang, V., Chen, X., Lim, L. y Chu-Ren, H. (2023). Framing COVID-19 reporting in the Macau Daily News using metaphors and gain/loss prospects: a war for collective gains. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10(482), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01994-3

Zamudio, A., Montero-López, L. y García, B. (2022). Acción colectiva en el 8 de marzo, prueba empírica de tres modelos teóricos. Psicología Iberoamericana, 30(1). https://doi.org/10.48102/pi.v30i1.416

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS, FUNDING AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors’ contributions:

Conceptualization: Barreto-Galeano, María Idaly; Rico-Revelo, Diana; Velandia-Morales, Andrea; Garzón-Velandia, Diana Camila; Sabucedo-Cameselle, José Manuel. Formal analysis: Barreto-Galeano, María Idaly; Rico-Revelo, Diana; Velandia-Morales, Andrea; Garzón-Velandia, Diana Camila; and Sabucedo-Cameselle, José Manuel. Data curation: Aguilar-Pardo, David; Garzón-Velandia, Diana Camila; Carvajal-Builes, Juan Camilo; and Carrillo-Ramírez, Alexis. Drafting-Preparation of the original draft: Barreto-Galeano, María Idaly; Rico-Revelo, Diana; Velandia-Morales, Andrea; Aguilar-Pardo, David; Garzón-Velandia, Diana Camila; Carvajal-Builes, Juan Camilo; Carrillo-Ramírez, Alexis; and Sabucedo-Cameselle, José Manuel. Drafting-Revision and Editing: Barreto-Galeano, María Idaly; Rico-Revelo, Diana; and Garzón-Velandia, Diana Camila. Visualization: Barreto-Galeano, María Idaly; Rico-Revelo, Diana; Velandia-Morales, Andrea; Aguilar-Pardo, David; Garzón-Velandia, Diana Camila; Carvajal-Builes, Juan Camilo; Carrillo-Ramírez, Alexis; and Sabucedo-Cameselle, José Manuel. Supervision: Barreto-Galeano, María Idaly; Rico-Revelo, Diana; and Sabucedo-Cameselle, José Manuel. Project management: Barreto-Galeano, María Idaly; Rico-Revelo, Diana; and Sabucedo-Cameselle, José Manuel. All authors have read and accepted the published version of the manuscript: Barreto-Galeano, María Idaly; Rico-Revelo, Diana; Velandia-Morales, Andrea; Aguilar-Pardo, David; Garzón-Velandia, Diana Camila; Carvajal-Builes, Juan Camilo; Carrillo-Ramírez, Alexis; and Sabucedo-Cameselle, José Manuel.

AUTHORS:

María Idaly Barreto-Galeano

Catholic University of Colombia.

PhD in Psychology from the University of Santiago de Compostela. Senior Researcher (Minciencias) linked to the Europsis research group (Category A1) in the line of social, political and community psychology at the Catholic University of Colombia. At the same University, she is Academic Vice-Dean and Associate Professor of the Doctoral Program in Psychology. Her research focuses on the study of language, political communication and its implications in conflict de-escalation, reconciliation and the construction of peace cultures. She is a member of the Observatory of Digital Social Networks for Studies in Psychology and the Political Psychology Node of the Colombian Association of Psychology Faculties (ASCOFAPSI).

Índice H: 22

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3677-852X

Scopus ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=33567621100

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=Zcw9I8QAAAAJn&user=Zcw9I8QAAAAJ

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Idaly-Barreto

Academia.edu: https://ucatolica.academia.edu/Mar%C3%ADaBarreto

Dialnet: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/autor?codigo=1908134

Diana Rico-Revelo

University of the North Department of Political Science and International Relations.

PhD in contemporary political processes, linked to the research group Conflicts and Postconflicts from the Caribbean (Category A) in the line of transitional justice at the University of the North in Barranquilla, Colombia. At the same University, she is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science and International Relations. Her research focuses on the study of political behavior, social movements and peace building. She is a member of the Observatory of Digital Social Networks for Psychology Studies. She is a member of the Board of Directors of the Colombian Association of Political Science (ACCPOL) and of the International Scientific Network of Studies in Territory and Culture (RETEC).

Índice H: 7

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3313-131X

Scopus ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=57193415015

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=WQYI1EgAAAAJ&hl=es

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Diana-Rico-Revelo

Andrea Velandia-Morales

Catholic University of Colombia. University of Santiago de Compostela.

PhD in Psychology from the University of Granada - Spain. Postdoctoral Juan de la Cierva in the COSOYPA research group at the University of Santiago de Compostela, in the line of analysis of the cognitive-emotional dimensions involved in political attitudes and behaviors. Her research focuses on the study of the effects of economic inequality on consumption behavior and related ideological and psychological variables. As well as gender stereotypes, sexism in advertising and its effects on the maintenance of gender inequality. Member of the Observatory of Digital Social Networks for Psychology Studies.

Índice H: 12

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8388-0984

Scopus ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=42263009400

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=7bQI-0wAAAAJ&hl=es

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Andrea-Velandia-Morales

David Aguilar-Pardo

Catholic University of Colombia.

PhD in Psychology from the Complutense University of Madrid. Junior Researcher (Minciencias) linked to the Europsis research group (Category A1) in the line of social, political and community psychology at the Catholic University of Colombia. In this same University, he works as assistant professor in the School of Psychology. His research focuses on the evolution of the brain, the expression of prosocial behaviors, social neuroscience and the structure of social networks. He is a member of the Observatory of Digital Social Networks for Studies in Psychology whose objective is to systematically monitor the digital verbal production associated with violence and cultural peace in specific social and political contexts.

Índice H: 6

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2197-1346

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=HW6TAPkAAAAJ&hl=es

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/David-Aguilar-Pardo

Diana Camila Garzón-Velandia

Catholic University of Colombia.

Psychologist, Master in Psychology from the Catholic University of Colombia and PhD student in Psychological Processes and Social Behavior at the University of Santiago de Compostela. Professor at the School of Psychology of the Catholic University of Colombia and junior researcher in the Europsis research group (category A1 Minciencias) in the line of social, political and community psychology. Her research focuses on political polarization, intergroup relations, political behavior and the construction of peace cultures. She is a member of the Observatory of Digital Social Networks for Studies in Psychology whose objective is to systematically monitor the digital verbal production associated with violence and cultural peace in specific social and political contexts.

School of Psychology

Índice H: 3

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9561-5021

Scopus ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=57214916091

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=YN64I6YAAAAJ&hl=en

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Diana-Camila-Garzon-Velandia

Academia.edu: https://ucatolica.academia.edu/CamilaGarz%C3%B3n

Dialnet: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/autor?codigo=5596758

Juan Camilo Carvajal-Builes

Catholic University of Colombia.

PhD in psychology from the Catholic University of Colombia. Linked to the Europsis research group (category A1 Minciencias) in the line of legal and criminological psychology. He works at the same university as Coordinator of the specialization and laboratory of legal and criminological psychology, as well as a teacher attached to the PhD program in psychology. His research has focused on legal psychology, especially on issues related to the psychology of testimony, psychology and forensic psychopathology. He is a member of the Observatory of Digital Social Networks for Psychology Studies, as well as of the Legal Psychology Node of ASCOFAPSI. He works as a consultant and private forensic expert in different areas of law.

Índice H: 2

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8928-6604

Scopus ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=57208257225

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com.mx/citations?user=e0fxjXAAAAAJ&hl=es&oi=ao

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Juan-Carvajal-8

Academia: https://ucatolica.academia.edu/JuanCamiloCarvajalBuiles?from_navbar=true

Alexis Carrillo-Ramírez

Catholic University of Colombia. University of La Laguna.

Psychologist and Master's degree in Psychology from the Catholic University of Colombia. PhD student in psychology at the University of La Laguna (Spain), with experience in development of Advanced Analytical Models, Statistics, Psychometrics and University Teaching. He has been a consultant in projects of statistical test management, multivariate methods, Machine Learning and Data Mining applications in R, SQL and Python languages. He has also developed scientific research, design, analysis and evaluation of psychometric tests. His lines of research are: statistical modeling with multivariate analysis methods, stimulus equivalence simulations in artificial neural networks and machine learning algorithms.

Índice H: 2

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9429-3494

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=E-raXpcAAAAJ&hl=en

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Alexis-Carrillo-Ramirez-2

José Manuel Sabucedo-Cameselle

University of Santiago de Compostela.

Psychologist and PhD in Psychology from the University of Santiago de Compostela with extensive research experience in social, political and environmental psychology. Professor at the School of Psychology of the University of Santiago de Compostela (Spain). Promoter and President of the Spanish Scientific Society of Social Psychology (SCEPS). Senior researcher of the Social Behavior and Applied Psychometry research group (COSOYPA). His research focuses on the study of social psychology, social movements, behavior and environment and attitudes. He is a member of the Observatory of Digital Social Networks for Psychology Studies.

Índice H: 38

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3002-851X

Scopus ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=6602637958

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=TPl7-DgAAAAJ&hl=en

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jose-Manuel-Sabucedo

Academia: https://independent.academia.edu/jsabucedo

Dialnet: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/autor?codigo=109170