Revista Latina de Comunicación Social ISSN 1138-5820 / No. 83, 01-24.

The identity construction of young people from gender and sexual diversity in digital social networks: claiming performative practices

La construcción identitaria de jóvenes de la diversidad sexo genérica en las redes sociodigitales: prácticas performativas reivindicativas

Paola Margarita Chaparro-Medina

Autonomous University of Chihuahua. Mexico.

Rubén Cervantes Hernández

Inter-American University for Development, Zacatecas. Mexico.

![]()

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Currently, digital social networks are an important means for sexual and gender identity configuration in LGBTIQA+ young people. Through these networks, people's capacity for agency is developed; particularly of young people whose sexual orientation and gender identity are on the borders of the heteronormative matrix. In this qualitative research, the objective is to investigate the manifestations of agency capacity in young people of gender and gender diversity through the use of digital social networks (DSNs) in the process of construction and expression of their gender and gender identities. sexual orientation, considering online practices and their possibilities for dissent from the heteronormative matrix. Methodology: For this, a study was carried out with 68 young people from Zacatecas between 18 and 24 years of age who recognize themselves as part of the LGBTIQA+ population, exploring their experiences around their online practices according to their capacity for agency when dissenting from the matrix. heteronormative. Results: The data were interpreted through six categories emanating from Judith Butler's theory of gender performativity. It was found that, in effect, DSNs enable individual interactions and with others that allow them to build or reaffirm their own gender identity and sexual orientation. Discussion and Conclusions: Therefore, it could be affirmed that these spaces allow the development of online experiences, sociocultural practices of interaction, dialogue, knowledge and encounter, thus generating meaning processes that build or reinforce identities that are enriched by the possibilities of sexual-gender diversity.

Keywords: digital social networks; LGBTIQA+; Identity; Young people; Performativity.

RESUMEN

Introducción: En la actualidad, las redes sociodigitales son un medio importante para la configuración identitaria sexual y de género en las juventudes LGBTIQA+. A través de dichas redes se desarrolla la capacidad de agencia de las personas; particularmente de jóvenes cuya orientación sexual e identidad de género se encuentran en los lindes de la matriz heteronormativa. En esta investigación de corte cualitativo, el objetivo es indagar en las manifestaciones de la capacidad de agencia en jóvenes de la diversidad sexo-genérica a través del uso de las redes sociodigitales (RSD) en el proceso de construcción y expresión de sus identidades de género y orientación sexual, considerando las prácticas en línea y sus posibilidades para disentir de la matriz heteronormativa. Metodología: Se realizó un estudio con 68 jóvenes de Zacatecas de entre 18 a 24 años que se reconocen como parte de la población LGBTIQA+ explorando sus experiencias en relación con sus prácticas en línea y su capacidad de agencia al disidir de la matriz heteronormativa. Resultados: Los datos se interpretaron a través de seis categorías emanadas de la teoría de la performatividad de género de Judith Butler. Se encontró que, en efecto, las RSD posibilitan interacciones individuales y con otros que permiten construir o reafirmar su propia identidad de género y orientación sexual. Discusión y conclusión: Por tanto, podríamos afirmar que estos espacios permiten el desenvolvimiento de experiencias en línea, prácticas socioculturales de interacción, diálogo, conocimiento y encuentro, generando así procesos de significación que construyen o refuerzan identidades que se enriquecen en las posibilidades de la diversidad sexo-genérica.

Palabras Clave: Redes sociodigitales; LGBTIQA+; Identidad; Juventudes; Performatividad.

1. INTRODUCTION

The heteronormative matrix (HM) is in charge of organizing the relationships, values, beliefs, ideals and desires of human groups around their sexuality and gender. This is integrated into the social context by determining a hierarchical position between human beings who conform to the norms and those who dissent from them. In this sense, when considering the different ways that are shaped in the digital social platforms, it has been possible to observe spaces in which the resignification of gender identity and sexual orientation becomes possible, as well as the experiences that emerge from other registers that are not the heteronormative ones. This leads to a questioning, redefinition and/or vindication of identity attitudes in people who dissent from the norms around gender and sexuality imposed by such matrix (Butler, 2019b; Chuca, 2019). But how does this take place, how does the HM manage to establish a framework for the shaping of gender identity and sexual orientation?

In principle, the functioning of the HM is effected by a series of norms and policies that subjects follow through the reiteration of performative acts, these can be oral, written, visual or kinesic acts (Butler, 2019a; Hernández and Pérez, 2019). These actions allow bodies to become intelligible in sexual and gender identities concordant or discordant with the rules of the HM (Fonseca and Quintero, 2009). In this way, the social recognition of bodies in feminine and masculine versions, reinforce the very binary normative of the cisheterosexual regime, generating an exclusion of practices that subvert this ordering (Barquet and Parra, 2021; Canseco, 2018). Therefore, those individuals who distance themselves from the norm imposed by the matrix are positioned in a situation that hinders the possibilities of social recognition, so that access to rights may be hindered or even made impossible by the hierarchical demarcation that arises from the HM (Cano, 2014; García, 2016). Thus, young people with sex-gender diversity, by circumscribing themselves outside the cisheteronormative guidelines, are people who are exposed to living in conditions of precariousness; the latter understood as the lack of human networks and lack of resources necessary to achieve full human development from a substantive level of dignity (Casales, 2023; Montenegro et al., 2020; Nijensohn, 2023). In addition, young people living under sex-gender diversity have the capacity for agency as a method of temporary escape from the HM. Thus, this allows an identity conformation affirmed by their own will and from a multiplicity of possibilities that are not limited to the HM.

One way of expressing their construction of identity and agency is through digital social networks (DSNs) because in them there is the facility to meet other people who have also been rejected by the norms of the HM. And this is how the DSNs connect different individualities generating the possibility of conversing, arranging meetings and generating acts of consumption of signs (Carbonell, 2016; Gardner and Davis, 2014; Gutiérrez et al., 2019; Rovira, 2017; van Dijck, 2019; Winocur and Sánchez, 2015).

In the context of young sexually divergent individuals in Zacatecas, their reality acquires specific nuances given that it is still a society that retains deep-rooted conventionalism. Although there have been some advances in the acceptance and understanding of sexual and gender diversity in Mexico, Zacatecas is a region that shows a society that continues to maintain traditional norms and conservative values in many aspects. These rigid social structures can generate greater resistance to the full inclusion of sexual and gender diversity. Therefore, the persistence of stigmatization and discrimination, which often stem from perceptions rooted in traditional cultural norms, can mark offline interactions. In this sociocultural environment, the sex-gender diverse population may encounter additional obstacles to freely express their sexual identity and orientation in everyday settings, as well as to access services and institutions that should guarantee their equality and well-being (Romo, 2023).

In relation to the above, the sociocultural processes that shape gender identity and amplify the diversity of sexual orientations take place through the consumption of signs that not only take place in offline life, but also through the possibility of accessing other environments and forms of signification coming from virtual platforms. In this way, this paper understands the “consumption” of signs as the exchange of personal data related to practices and tastes that are processed by the algorithms of digital platforms in a realm of constant connectivity (Bauman, 2007; van Dijck, 2019). Human beings signify and interpret what they are through the signs that are provided by images, videos, textualities and ideograms, broadening their panorama of diversity in terms of gender and sexual orientation positions. Therefore, the interactions that occur through digital platforms become essential because they shape sociocultural processes through the experiences and consumption of signs in the DSNs.

2. Performativity in digitals social networks: notes for understanding identity formation processes

This paper argues that, at present, interconnectivity in virtual spaces does not allow identifying a clear delimitation between offline and online experiences; on the contrary, the constant in our days is the mutual construction between physical and online experiences (de Abreu, 2014). Therefore, when we refer to the consumption of signs, symbols and discourses in the DSNs, it can be understood that interpersonal relationships are simultaneously established in real time and in different geographies. This amplifies the circulation of ideas and the production of signs to shape identities with a greater degree of freedom, but mainly with a direct impact on the materiality and the surrounding reality of young people as the main users (Guattari, 2004; Lazzarato, 2006).

As argued in the introduction, the HM directs, manages and conducts gender identity to be intelligible within the framework of the binary cisheteronormative, i.e., the limitation to two genders: female and male (Vázquez, 2020). In turn, this establishes a hierarchical level according to whether the bodies of one or the other are concordant. Consequently, bodies that do not identify with either of these two restrictive options are excluded and made invisible, turning them into abject identities (Hining and Filgueiras, 2022).

In accordance with the above, the modes of socializing in tangible spaces occur through institutions that practice the “disciplining” of subjects by controlling bodies and behaviors to repress expression and desire through the narrative discourse of the HM (Bernini, 2018; Domínguez-Ruvalcaba, 2019). On the other hand, the HM functions through the installation of a set of norms and performative acts (oral, written, gestural or bodily acts that combine language with action); in other words, it acts through what is called gender performativity (Butler, 2019a; 2019b).

Gender performativity refers to the various acts that have the capacity to signify and act at the same time, influencing the shaping of sexual and gender identities (Gros, 2016); that is, the ways in which subjects position themselves and recognize themselves in the guidelines established by the HM. The repetition of the discourses, practices and actions of gender norms has an incorporation in the body, identified as incardination (Braidotti, 1999). All of the above is manifested as a creative mechanism of the ways in which the spheres of desire, the corporeal and the identity position in gender are assumed.

The HM leads to frame the way in which the subject's behavior is ascribed to the social and cultural norms related to what is understood as “acceptably” feminine or masculine, as the case may be (Rodriguez, 2008). Certainly, it is recognized that the male-female binomial is insufficient to account for the diversity of gender variants. The effect that has been achieved in society has been the incorporation of discursive components that are rethinking our practices and the actions that make visible the conformation of dissident identities. In this sense, this study provides an identification and understanding of the ways in which the openness raised by connectivity generates other possibilities that crack the rigid framework imposed by the HM through various ways of accessing information and sharing experiences among young people.

The Internet is ambivalent in the possibilities of identity development due to the fact that individuals who are in such DSNs deploy a diversity of meanings and expressions related to gender (Lazzarato, 2012). For those who identify themselves as LGBTIQA+, DSNs facilitate their identity development (Craig and McInroy, 2014) because in these there are resources that differ from traditional media, which usually represent the collective in a stereotypical way (McInroy and Craig, 2017). Likewise, it is found that young people who use DSNs are more involved with their identity and, therefore, with communities related to their interests and positions, as dissident subjects of the cisheteronorm. Therefore, a space is created in which they can feel safe and supported, to the extent that they can seek information, or resources related to their sexual identity or gender orientation (McInroy et al., 2019).

However, accessibility, in turn, is related to a level of exposure in a space where interaction does not necessarily take place in a safe and tolerant manner with diversity. In these terms, privacy and data protection policies are fundamental to protect the privacy of users and to ensure a protected experience in relation to the information that is shared publicly. In turn, it is important to consider the ways in which data generated by sex-diverse people on digital platforms are used for decision making within the data mining scheme; this refers to what Guyan (2022) proposes, in what he calls queer data. Queer data conforms categories of sex-gender diversity, arranging and defining a transnormative scheme that makes difference possible, but in a delimited and stereotyped manner.

On the other hand, in agreement with Saez (2024), DSNs are indeed a contribution to the identity configuration of young people, particularly of people in gender diversity, due to the possible multimodal writing and interactivity practices, through the use of images as constitutive elements of the narratives and the creative deployment of the corporealities posted in the DSNs, which allows the conformation of an autobiographical space of visibility from which to constitute an opening to the encounter and dialogue with diversity (Henaro and Peniche, 2021). In these terms, the visual, framed in the logic of the current digital era, allows ways of inhabiting and constructing spaces away from the HM, that which Trejo (2022) recognizes in body images as an exercise of incarnation of the imaginary of the possible, generating a break with the cisheteronormative, even with the cisgendered. The positioning of the body-image through instantaneous reproducibility generates a micropolitical articulation, in the encounter that generates a search for creativity on each of the bodies. Therefore, queer data, to the extent that it conveys information about the experiences of people who identify within the LGBTIQA+ collective, amplifies the desire for self-determination in gender (Guyan, 2022).

In contrast, it can be seen, both in the literature on gender-based violence on digital platforms and in the experiences of the participants in this study, that, due to gender-related aspects, symbolic and psychological violence, as well as discriminatory practices and hate speech are present in the DSNs with an increase in their manifestation (Anti-Defamation League, 2021). This is due to the moral disconnection that it generates in some people because they feel less responsible for their actions due to the fact that they are physically separated or because of online anonymity (Rivera-Martín et al., 2022). The very design of digital social networks, both because of anonymity and algorithms that generate polarization and facilitate the dissemination of controversial content, contribute to these harmful practices that generate unsafe and less respectful digital spaces for coexistence (Vega et al. 2024).

On the other hand, the question arises as to why sex-gender youth feel more comfortable to develop their identity online, some possibilities are due to the fact that Mexico is the second country with more transphobia and homophobia crimes (Letra ese, 2020), in addition, according to the National Diagnosis on discrimination against LGBTI people in Mexico, it is considered that sexual orientation or gender identity has been an obstacle to work (Comisión Ejecutiva de Atención a Víctimas and Fundación Arcoíris, 2018). In addition to these data, it is known that, in cases of school bullying, authorities do not usually intervene in this type of situations, and this allows the emergence of a lesbo-trans-homophobic language normalized by students, and even by some authorities, thus perpetuating a permanent cycle of harassment (Baruch et al., 2017). Similarly, it is known that society rejects coexisting in the private sphere with trans people (37%) and gays or lesbians (32.5%) of any age (Consejo Nacional para Prevenir la Discriminación et al., 2017). Although there are no statistics or studies for Zacatecas, it can be considered a conservative state, due to the late approval of same-sex marriage at the national level. In these terms, it is essential to know the experiences of young people of gender diversity in relation to the use and consumption of signs in the DSNs in relation to the processes of shaping their gender identities. Thus, the following questions are posed in this study: How are the processes of identity construction of young people of gender diversity in digital social networks? What are the identity manifestations that are deployed in relation to the expression of their gender identities and sexual orientation? What are the challenges and opportunities faced by young sexually divergent people in expressing their gender identity and sexual orientation in digital social networks?

3. OBJECTIVES

In order to address the questions posed in the previous section, the general objective of this research is to investigate the processes of identity construction of young people with gender diversity in Zacatecas, Mexico, through their experiences in the use of digital social networks.

In these terms, the specific objectives are the following:

- To identify the main platforms of digital social networks used by young people with sex-gender diversity to express their gender identity and/or sexual orientation.

- To explore the diverse identity manifestations that young people with sex-gender diversity deploy in digital social networks, in relation to the expression of their gender identities and/or sexual orientation from their own perspective.

- To analyze the challenges and opportunities that young sexually divergent people experience when expressing their gender identity and/or sexual orientation.

These objectives have been proposed with the intention of valuing the situated experiences of young people in a given context, while expanding the existing lines of research within the field of gender studies by delving into the processes of identity formation from the experiences of the subjects themselves. In these terms, the aim is to enrich the debate in the understanding of the negotiation and embedding of gender identities and/or sexual orientations in the contemporary context from the intersection between gender, technology and digital culture.

4. METHODOLOGY

This study was designed under the guidelines of the grounded (Strauss and Corbin, 2002), constructivist and interpretive (Palacios, 2021) theory, seeking to analyze Butler's HM, which belongs to queer studies (Torres and Moreno, 2021). To carry out the data production, a call was launched on Facebook, in which 75 people answered the interview and only the data on the experiences of 68 participating subjects were taken into account because only them answered the interview in its entirety. The sample was formed by convenience. The research design, corresponding to the Grounded Theory under the interpretative hermeneutic paradigm, is positioned as a non-representative sample. For this purpose, qualitative cross-sectional research was carried out.

The participants who attended the call do not represent the totality of the LGBTIQA+ acronym. Therefore, the decision was made to approach the research from the concept of gender diversity (Salín-Pascual, 2015). This concept allowed us to expand categories that may be limited, even unrecognized by people who, although they declare themselves dissidents of the cisheteronormative matrix, on the other hand, may not necessarily recognize themselves within the limits of the range of identities and orientations present in these acronyms.

Although the approach in this research is fundamentally qualitative, some quantitative data were collected as a result of the initial questionnaire that allowed the fulfillment of one of the specific objectives related to the identification of the main DSNs used by the participants. Therefore, a guideline of 18 questions related to identity formation and DSNs consumption was developed, as well as the production of data. Through the questions asked, each participant expressed the way in which they have developed their agency using DSNs for their processes of identity formation as a sexually divergent subject. In this way, data were systematically produced to describe these experiences.

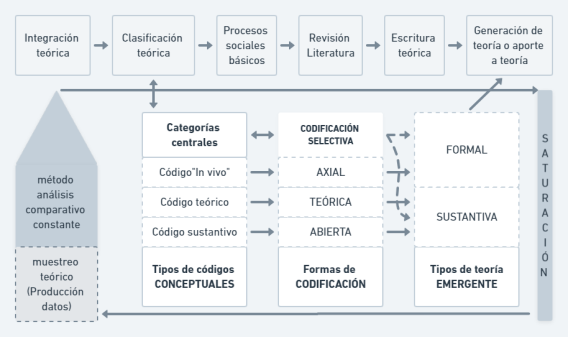

Among the proposals of grounded theory, we have positioned ourselves in selective coding based on substantive codes, therefore, in this work a substantive theory was conducted; that is, a contribution was made to existing theories by identifying and establishing a relationship between the data obtained with the concepts proposed by the theory through the constant comparative method (Maxwell, 2019; Wodak and Meyer, 2003). By using this method, it was fundamental to identify the meanings of young people in the use of the DSNs to construct their identity. Also, the interrelations between concepts and field data were explored, favoring the understanding of the object of study. For this reason, such a strategy required data saturation and not representativeness. For a broad understanding of GT, see Figure 1.

Figure 1: Basic components of the grounded theory.

Source: Elaborated by the authors based on Contreras et al. (2020); Estrada-Acuña et al. (2021); Vives and Hamui (2021).

Therefore, for the selection of participants for this study, the authors resorted to searching for people who participated in DSNs through organic advertising in LGBTIQA+ groups for residents in the state of Zacatecas, Mexico. The production of the data was carried out from July to August 2022, with informed consent authorizing the use of the data through anonymous participation.

The selection criteria for the participants were as follows:

1. Individuals who identified themselves as part of the sex-divergent population.

2. People enrolled in DSNs groups related to LGBTIQA+ issues and sex-gender diversities.

3. Age range between 18 and 24 years old. In such a way that they could expose, in retrospect, their experiences regarding their process of identity formation and reaffirmation of their sexual orientation through the use of digital social platforms.

A guideline with four blocks of questions was elaborated and analyzed by four experts in the subject with doctoral degrees, whose contributions and suggestions allowed adaptations to be made with a higher level of use of the context of the participants. The first block of specific questions referred to general data relevant to this study, such as age, sexual orientation, gender identity, marital status and educational level. The second block inquired about the age at which people began to use DSNs and at which they identified themselves as people with gender diversity, as well as the frequency of the DSNs they use and the main uses they make of them. In the third block, using both general and specific questions, the type of activities carried out through digital social platforms were explored. These were related to the search for information on LGBTIQA+ issues and the development of practices and uses, such as: social, cultural, political events and activism of the LGBTIQA+ community.

The first three blocks allowed the generation of quantitative data to have a better knowledge of the sample, as well as of their usual online practices; however, the focus of the data analysis is addressed from the richness of the contribution of the qualitative data of the participants to account for the processes of construction and expression of their gender identities and sexual orientation in the online practices.

Thus, in the fourth block, by means of a guideline of open questions, a flexible and open strategy was established, focusing attention on life experiences and their processes of identity formation. Here the participants expressed their experiences, where DSNs could be identified as enabling their processes of gender self-identification and sexual orientation. In addition, they evidenced experiences that negatively affected their way of accepting their sexual orientation or gender identity when using the DSNs. In turn, they were questioned about practices that may or may not be performed in the same way in offline and online life. To sum up, 68 people participated and provided their experiences individually, guided by the questionnaire described above, obtaining with the resulting data the categories described in Table 1.

Table 1. Description of the categories.

|

CATEGORIES |

|

Expression and manifestation of gender. ways in which we develop and express ourselves corporeally (materiality), semiotically (gestures, movements, signs) and linguistically (discourses about our attitude in gender and our sexuality). |

|

Precariousness. A condition that determines the degree of protection that a subject will have within an institutional scheme. |

|

Recognition. A performative practice that, while making visible, at the same time enacts and activates the act of recognition as an intelligible subject from dissident viewpoints. |

|

Process of reiteration. Discourses, technologies, practices, actions and attitudes that represent gender regulations in a specific context and that have as an effect the conformation of a legible subject in the binary sex-gender scheme. |

|

Disidentification from regulatory norms. The possibility of assuming a gendered and sexed position that rejects the heteronormative framework, or else, expands the possibilities imposed from the binary logic. |

|

Identifying practices. The practices that constitute an operation that produces the possibilities of intelligibility of bodies. |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

5. RESULTS

As part of the general data obtained in the first block of questions, the participants in this study positioned their sexual orientation as follows: gay (39), bisexual (15), lesbian (7), pansexual (4), asexual (2) and demisexual (1). With respect to gender identity, they were positioned as follows: cisgender (52) gender fluid (8), non-binary (5), agender (2) and androgynous (1). Whose maximum schooling is expressed as follows: 34 college graduates, 32 high school graduates and 2 middle school graduates.

In relation to the data from the second block of questions, the age ranges in which they began to use the DSNs were expressed as follows: between 6 and 9 years of age, 17.54%; between 10 and 12 years of age, 33.8%; between 13 and 15 years of age, 39.7%; between 16 and 18 years of age, 8.8%. Therefore, the predominant age of initiation of DSNs use is during adolescence, which coincides with the key period for the formation of a person's identity. On the other hand, regarding the most frequently used DSNs, Facebook (100%) maintains predominance and is followed by Instagram (73%). The most common uses of both platforms are, primarily, to search for information, to get to know better the people with whom they relate, to meet new people and also to share their tastes and interests with their friends. Some other DSNs mentioned were: WhatsApp (67%), Twitter (43.90%), YouTube (26.82%), TikTok (20.73%), Grindr (18.29%), Tinder (15.85%), Google (14.63%), Kik (2.43%), Tumblr (2.43%), Twitch (2.43%), Telegram (1.22%), Bumble (1.22%) and Moovz (1.22%).

In the third block, particularly located in identifying the uses of DSNs, it was possible to find the prevalence of 61 people who mentioned using DSNs to obtain information and learn about their sexual orientation or gender identity. On the other hand, the same number of people mentioned getting information on the DSNs about LGBTIQA+ issues in general. In addition, 80.9% looked for people to talk to about their sexual orientation or gender identity. This data, in principle, shows that the DSNs are a viable space to engage in conversations and socialization practices with like-minded people, or, in front of whom it is possible to talk about the position on gender and sexual orientation. In addition, 97% mentioned using the DSNs to establish friendships, while 76.4% mentioned using them to arrange dates and, finally, 58.8% mentioned using them to arrange sexual encounters. Based on these data, we can affirm that the DSNs are media that allow us to form friendships, as well as to meet like-minded people to go out with.

Finally, according to the fourth block, it was found that the use of DSNs around the search for LGBTIQA+ social and cultural events was 69%, while political participation in associations, collectives or groups that promote activism and the expansion of rights of the LGBTIQA+ population was 58.8%. These data are important given that they show us the diversified uses of the DSNs with the scope of sociability, considering the cultural, social activities and activism practices mediated through these platforms. However, there is the limitation that the participants, when talking about activism and politics, did not necessarily relate it to gender dissidence.

5.1. Categories

In this research, the starting point has been constituted by the experiences exposed by the participants, however, in order to make an interpretation that facilitates achieving a greater degree of understanding, we resorted to Judith Butler's theory of gender performativity (2009, 2019a, 2019b) to generate an articulation between the concepts on performative acts, in contrast with the codes obtained by the empirical information. From this theoretical perspective we can consider that performativity produces an illusion of naturalness regarding gender, through the repetition of gestures, discourses and practices installed within the convention of the cisheteronormative scheme. However, the convention that makes it plausible for an illocutionary (performative) utterance to produce that which it enunciates is not assured in every context. In other words, the state of affairs changes in certain contexts.

In these terms, the guideline provided by this perspective is to emphasize the importance of the interaction of the requirement of the other to make and position oneself in the gender from the social interaction, as well as to consider the convention that sets its regulation. However, within the openness that is granted to future generations through agency there is a normative regulatory framework. In this sense, by abandoning the rigidity of considering gender and desire as something given, it is understood that it is a conformation through constant reiteration, so that it is understood that the DSNs generate interactions that install ways to position oneself in gender identity and sexual orientation.

Therefore, it has been considered necessary to introduce concepts that approach Butler's theory to encompass the relationship of gender identity development and sexual orientations through the use of DSNs. For this purpose, the following categories were established:

5.1.1. Expression and manifestation of gender

This constitutes the ways in which people show themselves, reproducing the norms of the HM within a frame, generally binary (male/female). The above establishes the ways in which we perform and express ourselves both corporeally (materiality), semiotically (gestures, movements, signs) and linguistically (discourses about our viewpoint in gender and our sexuality) (Butler, 2009). Participants were asked to state an experience involving the use of DSNss for the purpose of identifying their sexual orientation or gender identity:

I could not express myself freely with my family, even though I came out of the closet, I cannot be myself because they criticize me. I consider myself a masculine guy, but from time to time I explore my femininity, but with my family I could not express it at any time and social networks or my friends are my place where I can be myself. (Participant 19).

As the subject mentioned, the HM limits her expression in her offline space, while online life, allows her to feel as she defines herself without having to maintain behaviors typically characterized as masculine within the HM. In the previous quote it can be noticed that gender and desire norms establish a regulatory imposition regarding the ways in which it is possible to express one's gender-related sexual orientation. The following is a quote from a participant who identified as a lesbian:

In networks I can upload a picture where I am with my girlfriend and express love and in everyday life I don't hold my girlfriend's hand in the street. (Participant 32).

The young woman has conflict in being able to socially express her sexual orientation due to the context that has permeated her socially and, thus, it can be inferred that she fears sanctions for not aligning herself with the imposed regulations. In both cases, people consider that the DSNs are the space that gives them the possibility to express and manifest their genuine feelings in accordance with their sexual orientation in front of other people.

5.1.2. Precariousness

This is the condition that determines the degree of protection that a subject will have within an institutional scheme. This is related to gender norms, to the extent that these determine the intelligibility of the subjects, that is, the way in which they can present themselves, expose themselves and be recognized within the social space. Gender norms, by taking into consideration the masculine and feminine as what makes possible the intelligibility of bodies, have the effect that those bodies that dissent from the regulations are prone to a greater degree of vulnerability in all aspects (Butler, 2009).

To demonstrate this category, the participants were asked about an experience that had had a negative impact on their way of perceiving or accepting themselves. From this, the following quote stands out:

A Facebook post that dealt with sexual orientation. In the comments on it, some people [talked about] that homosexuality was a very serious sin and that made me doubt and feel very bad about myself for being who I was; I didn't want to be a sinner or a bad person. (Participant 25).

Through these data, it was noted the problem that, in the DSNs, from various sources (family, friends, other users and followed pages), LGBTphobic comments were found that placed them in denial about their sexual or gender identity because of the discourses based on religion or the notion that exists in the HM about procreation. Coincidentally, another person mentioned:

On Facebook hate speeches are mostly spread making me at my twelve years old put a hindrance on my self-acceptance, but nowadays I know that there is nothing wrong with me. (Participant 14).

Through his process of configuring DSNs and physical spaces, it is observed that as time went by, the subject was resilient and self-accepted. It is inferred that the DSNs play both positive and negative roles in shaping their patterns, however, with the configurations of blocking, restricting, muting, among others, they can avoid certain situations that make them uncomfortable; thus limiting the HM in their digital spaces.

Given the above, it is possible to identify that situations of precariousness are generated in relation to gender standpoints, in each of the cases the ways in which people were affected are expressed, exposing them to situations in which an environment of vulnerability was generated, mainly with respect to sexual orientation. The dissemination of propaganda and/or hate speeches against them that aim to undervalue their sexual preferences and/or gender identities, generate not only insecurity, but also, a representation of LGBTIQA+ people that leads to the distortion of information perpetuating negative stereotypes, thus, sustaining a rigid scheme about diversity. This has the effect of misinformation in society, generating conflicts of both stigmatization and violence that expose people to greater degrees of vulnerability and the impossibility of accessing recognition rights.

5.1.3. Recognition

This condition occurs when, by complying with the gender norms defined in a given context, individuals become subjects that are recognizable by others. Now, at this point it is important to emphasize “in a given context”, given that this context can also refer to a virtual space defined by interactions that, when sustained over time, have an effect on the viability of being recognized as subjects. In these terms, bursting into a space, be it physical or virtual, from the standpoint of subjects who, from the way they experience their gender and sexuality, consider themselves as subjects of recognition, making the relationship with others expand the limits of being recognizable. Therefore, recognition is, strictly speaking, a performative practice that, while making visible, at the same time, enacts and activates the act of recognition as an intelligible subject from dissident positions.

A bisexual participant concisely indicated the role of DSNs:

[...] social networks have helped me a lot in my process of accepting my sexuality with videos and phrases that make me feel included and part of the community. (Participant 14).

Likewise, another participant mentions:

[...] when I opened my first social network [...] I was trying to free myself a little more [...] just like I was getting a lot of posts about the [LGBTIQA+] community and that's when Facebook knew what I was looking for and wanted [...] (Participant 18).

The participant already recognized herself as a lesbian and wanted to pursue her desires, which the network facilitated. So, by talking about community, communicative exchange with more people who recognize and identify themselves by their desires, experiences, habits and common interests was proven to take place.

The same person also expressed: “My family, often, would ask me the reason for those publications because, generally, they were not publications that a fourteen-year-old girl would make. They would question me and ask me: 'why are you posting women kissing?' My interest would increase and often Facebook would focus on finding people in the community.” It is observed in the quote that algorithms (these inscribe the user interaction, calibrate the content and platform models in the interface) play an essential role in the development of individuals through the DSNs by displaying signs or content to repeat patterns or tastes.

Recognition is a fundamental part in the identity conformation of every person, in the information provided by the participants it can be seen that the processes of acceptance are made possible to a great extent, thanks to the fact that other people recognize and assume diversity as a value. In this sense, the use of DSNs is essential to obtain videos and phrases that express gender expressions outside the cisheteronorm. In this way, validation and identification, based on the contents obtained from the different platforms, generate areas of support by providing resources and connectivity with other people with whom it is possible to share experiences, thus generating a sense of belonging and identity strengthening.

In the second participation, it can be observed that Facebook constitutes a neural platform to the extent that it allows the publication of photographs, and thus share, from images and textuality, experiences with other people whose preferences are either similar or complementary, in such a way that the expression of gender and the expression of sex-disident orientations becomes possible in a virtual environment. Thus, the process of recognition makes it possible to explore and find in relationships with like-minded people a greater meaning in relation to the possibilities in gender. It was possible to note that the DSNs, in short, play a preponderantly significant role in the recognition of sexual and gender identities, the acceptance in the diversity of groups and people, but mainly in the self-perception and self-identity conformation.

5.1.4. Reiteration process

It is the set of operations of repetition of gender norms that are imposed and, therefore, come from the heteronormative system. They are the discourses, technologies, practices, actions and attitudes that represent the gender regulations in a specific context and that have the effect of shaping a legible subject in the binary sex-gender scheme.

Now, reiteration is carried out in accordance with the material set of relations that sustain it, therefore, to the extent that those who question themselves displace the meanings of heteronormative discourses to the level of dissidence, then, reiteration is articulated in the materiality of a body yet to be created, in an open possibility from the plane of difference (Spargo, 2013). The processes of reiteration operate performatively, to the extent that they produce what they name. In turn, discursively, new ways of inhabiting gender are generated and the spaces generated in the DSNs operate under a set of conventions different from the HM. Thus, a practice of cultural rearticulation, or iterability, is produced, given that there is no totalizing context of experience, but rather, the proliferation of discourses creates new contexts in which signification is rearticulated.

This first participant interacts with other LGBTIQA+ people through which he obtains interactions and content that allow him to inform and understand himself and the community in general, expanding the degree of self-perception. He was asked if the DSNs had helped him to face situations that made him uncomfortable and his answer was affirmative:

Yes, because I relate very closely with people from the community or pages focused on it. In such a way that almost 80% of the content I consume belongs to the community and that has helped me to know and be more informed about diversity issues; it has also encourage me from my standpoint to share the content so it can let others read it and know that they are not alone. (Participant 19).

In this way the discourses are intertwined with vindicative practices that allow them to help other people in search of self-knowledge. This breadth of information generates processes of new possibilities to build identities in accordance with norms and values that escape hegemonic patterns.

The following quote shows how a person reiterates his sexual identity:

I was able to connect with people just like me, who had thought [or had] similar experiences and feelings.... I was able to name what I was experiencing. (Participant 46).

The connection established with other people makes it possible to name experiences and, therefore, to give meaning to their practices. On the other hand, the next participant mentions the repetition of the HM:

When I was about fourteen or fifteen years old, there were applications like “ask.fm” and “Secret” [...], On those kinds of platforms they came many times to offend me, telling me things like: Faggot, gay, [...]; which made me feel bad, thinking that what I was was wrong. [...] As time went by, that also empowered me to be what I am now and to feel proud of who I am. (Participant 24).

Likewise, the processes of reiteration become manifest through the collective construction of meanings, which also reaffirms people's own experiences. The encounter with other people who share experiences generates a space from which a recognition of difference is expressed and, therefore, practices that reproduce prejudices are overcome. This itself derives in the possibility or impossibility of generating an empowerment of people.

5.1.5. Disidentification of regulatory norms

Regulatory norms establish the practices that regulate, manage and delineate the meanings attached to the materiality of the body and the symbolic sphere in relation to the regulatory schemes of the HM. Therefore, disidentification is the possibility of assuming a generic and sexualized position that rejects the heteronormative framework, or expands the possibilities imposed by the binary logic (heterosexual male/female). In such a way that new ways of assuming oneself in gender and sexuality are generated (García-Granero, 2020; Pesquedua, 2023).

I started to doubt about my sexuality when I was eleven years old. I almost did not use the internet because of my parents, but when I took the computer and searched about it...of course, being cautious since I did not want to get in trouble with my parents [...] on Instagram, more than anything [where] I found a community in an app where they knew more about what I felt. I even started identifying as bisexual and I liked that label. After that I tried to be more open to [these issues] since I didn't consider it wrong to express myself the way I felt (Participant 7).

In the information provided, disidentification from regulatory norms is manifested in rejecting HM. This allowed the person to expand her possibilities beyond those forced by the HM, finding new ways of assuming her sexuality and positioning herself in gender. Obtaining information and establishing connections with other people's experiences and diverse modes of representation, through videos and photos, provided her with a space in which her identity could be expressed through validation, recognition and the search for authenticity. This example of disidentification make it possible to notice how powerful DSNs are insofar as they propose an encounter with forms of representation and practices that subvert the conventional categories of normative gender.

5.1.6. Identifying practices

These are actions that aim at resemblance with the other, mediated by the regulatory scheme of sexuation. The search for similarity is not an imitation that affects the conformation of the sexed body, but an imaginary projection that operates in the corporeal morphology (Butler, 2019a). These practices constitute an operation that creates the possibilities of intelligibility of bodies. In other words, to the extent that individuals recognize themselves in a regulatory scheme, their bodily self becomes possible by assuming sexed positions according to the possibilities of that scheme. In the case of the spaces that are shaped by social interaction in the DSNs, what can be seen is a delimitation of the imaginary space that expands.

Thus, in identifying practices it can be appreciated the conformation of regulatory spaces of sexuation that are suspended, or else, that are re-signified. Such is the case of the following participants:

[When I was twelve years old] I used YouTube to find out why I was attracted to other boys [and] I found hundreds of videos of people from the [LGBTIQA+.] community telling their experiences, which made me feel identified (Participant 9).

In view of the above, it is inferred that the subject identified himself by sharing with his peers, allowing him to outline a panorama of the range of possibilities he has to build himself. At this point, it is important to understand that, although an HM can be recognized, it is not something fixed and immutable; on the contrary, it is eminently historical.

For example, for the previous participant the regulations were stricter, but in this constant iteration through his capacity for agency, he was able to modify the impositions of the “original” rules and thus created a greater openness in this matrix, because although there are still regulatory impositions, there seems to be greater flexibility in certain digital and physical contexts according to the social, cultural, economic and political context. So that the regulation of the rules, although they are followed according to the HM, have mutated over the years according to what was exposed in the person's account. Likewise, this individual, identified as demisexual, responded:

By using the Google search engine [I asked] if there were more people like me and on Facebook I searched for groups. I was twelve years old when I started asking Google 'what was wrong with me' and I was happy to see that many of us were asking the same question (Participant 43).

Regarding the above, it is important to mention that identity configuration develops in a hybrid way between physical and digital environments, which implies the need for social interaction. This process includes the formation, internalization and manifestation of patterns, patterns, customs and norms of society (Pino and Alfonso, 2011). That is, to understand an individual and their actions, it is essential to consider the context in which they develop (González, 2017). Then, the DSNs are a blurred border of identity development where they can obtain information that in their physical environments would not be accessible. Returning to Butler, it is understood that the construction of the subject is given by the reiteration of norms and, in the case of these people, they remain as unintelligible subjects in their physical spaces, due to the HM and their desires, expressions and non cisheteronormative identities, remaining on the periphery at the same time that the DSNs serve as a device to displace their meanings by expanding their possibilities of being and existing by breaking the personal discourses and norms of the HM.

6. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

In short, the research purpose has been achieved: to investigate the manifestations of the capacity of agency in young people of gender diversity, through the use of digital social networks in the process of construction and expression of their gender identities and sexual orientation, considering online practices and their possibilities for dissidence from the heteronormative matrix.

This is not exempt from recognizing the innate difficulties of virtual spaces regarding the development and tolerance that users practice within the platforms. In this research the focus of attention was centered on identifying the possibilities in the opening of digital social spaces for a socialization that contributes to the subjective affirmation of young LGBTIQA+ people.

In summary, it is highlighted that the intelligibility of the subjects arises through the use of a series of devices such as discourses, technologies, practices and meanings without necessarily being articulated among themselves; however, these have a direct effect on the processes of subjectivation of individuals, both in their way of thinking and desiring and in their materiality in digital spaces and, sometimes, in physical spaces as well.

The categories made it possible to identify in the DSNs the meanings poured from young LGBTIQA+ people for their identity construction, as well as to explore the theory of performativity with the DSNs. The following is highlighted from the categories: in the “Expression and manifestation of gender” it was found that the participants are located in the borderline spaces of the HM, where they defy the regulations of the matrix by using technological tools to explore and express their sexual orientation and gender identity, in accordance with what was developed by Trejo Olvera (2022).

In the category of “Precariousness”, it was evidenced that people found LGBTphobic comments in the DSNs, similar to what was registered by the Anti-Defamation League (2021), which may come from their immediate circles or from unknown people based on religious discourses or the biomedical model (Gómez, 2009; Gómez, 2010), causing insecurity and discomfort in the acceptance of sexual preferences or gender identity.

The category of “Recognition” is considered vital for the configuration of subjectivity because the use of the DSNs allowed them to be recognized by other people fugitives to the understanding of the norms (highlighting that the algorithms facilitate this) and, with this, to strengthen their non-heteronormative identities. On the other hand, the “Reiteration process”, refers to the repetition of the norms imposed by the heteronormative system, however, when the meanings of the matrix discourses are displaced to dissidences there is a process of creation by the possibility of agency. The fifth category, “Disidentification of regulatory norms”, refers to the rejection of the heteronormative frame and expands the possibilities outside binarism, by feeling in community their experiences are validated, they represent and perform practices that escape from the conventional in the HM, thus giving them the possibility of identifying themselves; and finally, in “Identifying practices” it is rescued that it is given hybridly (online and offline) by the multiple possibilities of access to information and interaction between individuals.

With regard to the objectives set, throughout the different stages of the research, it was possible to investigate the processes of identity formation, in principle because, when asked about the age at which they began to use digital social networks, the average was between 13 and 15 years of age, an age that is precisely key in the developing identities. In turn, when starting with questions of this nature, the participants shared their experiences in terms of identity configuration processes, to the extent that they noticed the interactions, decisions and negotiations that define their life experiences. For their part, the specific objectives were achieved, as the main platforms used were identified, which are Facebook, followed by Instagram and thirdly WhatsApp. In addition to this, by exploring the identity manifestations in relation to gender and sexuality, there was found a great deal of diversity of ways of living and defining one’s own standpoint in gender, which has been raised in the results of this research. Likewise, challenges such as discrimination, stigma and hate speech that proliferate in the DSNs were identified, as well as opportunities such as support, empowerment, visibility and recognition as practices present and possible by the very design of the platforms that promote the match.

However, this research only focused on a sample in the state of Zacatecas, where the rigidity of the HM may mean a greater resistance to inclusion and openness to gender diversity, which implies a limitation to recognize the possibilities that the context may have on the capacity for agency in other spaces. Therefore, the generalization of the findings, although limited, generates possibilities for future research that allow a broader perspective in other geographic areas.

On the other hand, future research with a longitudinal approach could be carried out to capture transformations in the uses and consumption of the DSNs in relation to the practices of gender identity claims and the shaping of sexual orientations. Another point to highlight is the need to advance in methodological aspects that allow a deep understanding of the intertwining of offline and online experiences of young people, as well as to explore the ethical implications of online research that requires authenticity, ensuring privacy and ethical handling of data.

In summary, it is possible to conclude that there is no single regulatory scheme, although there is a hegemonic one, and this openness extends according to a given historical, cultural and social context. In the current predominant system, people with gender diversity are precarious due to difficulties in accessing their rights and violated because they do not fit into the binary system. Thus, the DSNs are fundamental because they allow them to access information and interactions that displace the boundaries of norms and enable identities outside the hegemonic. The participants found in digital spaces a place to regulate who relates to them and how; facilitating the expression and exploration of their desires to build themselves as intelligible subjects. Finally, it is not suggested that the DSNs are outside the HM, but that these spaces allow a margin for a safer identity development.

In terms of limitations, it is suggested to have an interview that is not structured in order to provide greater flexibility in obtaining a vast amount of data. It is also considered appropriate to have a smaller sample in order to be able to integrate questions that are not necessarily part of the guide. On the other hand, it is suggested that each of the categories described be expanded with its own interview, thus allowing the codes and subcodes to be extended. In addition, if only one category is covered, it may be easier to obtain data from both online and physical life and thus generate a comparison or contrast of the two. It is within this research scope to include both this and other theoretical scaffolding to carry out such interviews and, it is necessary as well to apply a basic data questionnaire for the study. Despite not being considered qualitative, it is useful to describe more of the sample and information of interest without going into depth. Finally, it is essential to create a homogeneous LGBTIQA+ study where each acronym is given representativeness; or only focus the study on one of these population groups in order to know the particular experiences and the creative possibilities of identity in plural terms.

7. REFERENCES

Anti-Defamation League. (2021). Online Hate and Harassment. The American Experience 2021. ADL’s Center for Technology and Society. https://bit.ly/49UHb9c

Barquet Muñoz, J. y Parra Vázquez, J. C. (2021). Aproximación a la teoría de la performatividad desde Judith Butler. ScientiAmericana, 2(8), 51-60. https://doi.org/10.30545/scientiamericana

Baruch Domínguez, R., Pérez Baeza, R., Valencia Toledano, J. y Rojas Córtes, A. (2017). Segunda Encuesta Nacional sobre Violencia Escolar basada en la Orientación Sexual, Identidad y Expresión de Género hacia Estudiantes LGBT en México. Coalición de Organizaciones contra el Bullying por Orientación Sexual, Identidad o Expresión de Género https://bit.ly/4297nKn

Bauman, Z. (2007). Vida de consumo. Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Bernini, L. (2018). Las teorías queer una introducción. Editorial Egales.

Braidotti, R. (1999). Diferencia sexual, incardinamiento y devenir. Mora, Revista Del Instituto Interdisciplinario de Estudios de Género, 5, 8-19. https://bit.ly/48ItXvy

Butler, J. (2009). Performatividad, precariedad y políticas sexuales. AIBR, Revista de Antropología Iberoamericana, 4(3), 321-336. https://doi.org/10.11156/aibr.040306

Butler, J. (2019a). Cuerpos que importan. Editorial Paidós.

Butler, J. (2019b). El género en disputa. El feminismo y la subversión de la identidad. Editorial Planeta.

Cano Abadía, M. (2014). Transformaciones performativas: agencia y vulnerabilidad en Judith Butler. OXÍMORA Revista Internacional de Ética y Política, 0(5), 1-16.

Canseco, A. (2018). Matrices y marcos: dos figuras del funcionamiento de las normas en la obra de Judith Butler. Areté, 30(1), 125-146. https://doi.org/10.18800/arete.201801.006

Carbonell, M. (2016). La vida en línea. Editorial Tirant.

Casales García, R. (2023). Identidad y performance: revisión crítica de la teoría de género de Butler desde Leibniz. Tópicos, Revista de Filosofía, 66, 97-118. https://doi.org/10.21555/top.v660.2159

Chuca, A. (2019). Metafísica y sentido común. La deconstrucción de la matriz heteronormativa en el pensamiento de Judith Butler. Question, 1(63), e168. https://doi.org/10.24215/16696581e168

Comisión Ejecutiva de Atención a Víctimas y Fundación Arcoíris. (2018). Diagnóstico nacional sobre la discriminación hacia personas LGBTI en México. Derecho al trabajo. https://bit.ly/3Pp15kE

Consejo Nacional para Prevenir la Discriminación, Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos e Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. (2017). Encuesta Nacional sobre Discriminación. https://bit.ly/4b3UwwY

Contreras Cuentas, M. M., Páramo Morales, D. y Rojano Alvarado, Y. N. (2020). The grounded theory as a theoretical construction methodology. Revista Científica Pensamiento y Gestión, 47, 283-306. https://doi.org/10.14482/pege.47.9147

Craig, S. L. y McInroy, L. (2014). You Can Form a Part of Yourself Online: The Influence of New Media on Identity Development and Coming Out for LGBTQ Youth. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Mental Health, 18(1), 95-109. https://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2013.777007

de Abreu, C. L. (2014). Géneros y sexualidades no heteronormativas en las redes sociales digitales [Tesis]. Universidad de Barcelon. http://www.tdx.cat/handle/10803/285404

Domínguez-Ruvalcaba, H. (2019). Latinoamérica queer. Cuerpo y política queer en América latina. Ediciones Culturales Paidós.

Estrada-Acuña, R. A., Arzuaga, M. A., Giraldo, C. V. y Cruz, F. (2021). Diferencias en el análisis de datos desde distintas versiones de la Teoría Fundamentada. EMPIRIA. Revista de Metodología de las Ciencias Sociales, 51, 185-229. https://doi.org/10.5944/empiria.51.2021.30812

Fonseca Hernández, C. y Quintero Soto, M. L. (2009). La Teoría Queer: la de-construcción de las sexualidades periféricas. Sociológica (México), 24(69), 43-60. https://acortar.link/Ay6hpB

García Manso, A. (2016). ¿Normas y géneros?: performatividad en Judith Butler y la teoría ciberfeminista. Revista Latina de Sociología, 6(2), 63-102. https://doi.org/10.17979/relaso.2016.6.2.1975

García-Granero, M. (2020). The problem of the depoliticization of “Gender” for feminist theory. Araucaria, 22(44), 203-228. https://doi.org/10.12795/araucaria.2020.i44.09

Gardner, H. y Davis, K. (2014). La generación app. Editorial Paidós.

Gómez Suárez, A. (2009). El sistema sexo/género y la etnicidad: sexualidades digitales y analógicas. Revista Mexicana de Sociología, 71(4), 675-713. http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0188-25032009000400003

Gómez Suárez, Á. (2010). Los sistemas sexo/género en distintas sociedades: modelos analógicos y digitales. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 130(1), 61-96. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/997/99717148003.pdf

González Monteagudo, C. (2017). La interacción en el camino hacia una comunicología. ALCANCE Revista Cubana de Información y Comunicación, 6(13), 142-172. https://bit.ly/3IFTLgJ

Gros, A. E. (2016). Judith Butler y Beatriz Preciado: una comparación de dos modelos teóricos de la construcción de la identidad de género en la teoría queer. Ciencias Sociales y Humanas, 16(30), 245-260. https://bit.ly/4akcyd1

Guattari, F. (2004). Plan sobre el planeta. Capitalismo mundial integrado y revoluciones moleculares. En R. Sánchez Cedillo (Ed.). Traficantes de sueños. https://bit.ly/3Ob9E1R

Gutiérrez Morales, I. M., Gutiérrez Cortes, F. e Islas Carmona, O. (2019). Comunidades virtuales y redes sociodigitales. Experiencias y retos. Editorial Flores.

Guyan, K. (2022). Queer data. Using Gender, Sex and Sexuality Data for Action. Bloomsbury Academic.

Hernández Rodríguez, A. I. y Pérez Rosales, E. J. (2019). Filosofías liminares y género: cuerpo discursivo y discurso corporal. Asparkía. Investigació Feminista, 34, 13-30. https://bit.ly/3Ptig4C

Henaro, S. y Peniche Montfort, E. (2021). Imágenes con agencia: (a propósito de visualidades frente a emergencias sociales). En Incitaciones transfeministas (pp. 155-163). Ediciones DocumentA/Escénicas.

Hining, A. P. y Filgueiras Toneli, M. J. (2022). La cisgeneridad y las políticas de enunciación en el transfeminismo brasileño. Athenea Digital. Revista de Pensamiento e Investigación Social, 22(2), e3033. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/athenea.3033

Lazzarato, M. (2006). Por una política menor. Acontecimiento y política en las sociedades de control. Traficantes de sueños. https://bit.ly/3Vp5zLC

Lazzarato, M. (2012). El funcionamiento de los signos y de las semióticas en el capitalismo contemporáneo. Palabra Clave, 15(3), 713-725. https://doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2012.15.3.15

Letra ese. (2020). Las vidas LGBTI + importan. Muertes violentas por orientación sexual e identidad de género en México. https://letraese.org.mx/crimes-de-odio/

Maxwell, J. A. (2019). Diseño de investigación cualitativa. Editorial Gedisa.

McInroy, L. B. y Craig, S. L. (2017). Perspectives of LGBTQ emerging adults on the depiction and impact of LGBTQ media representation. Journal of Youth Studies, 20(1), 32-46. https://bit.ly/3Tnez1f

McInroy, L. B., McCloskey, R. J., Craig, S. L. y Eaton, A. D. (2019). LGBTQ+ Youths’ Community Engagement and Resource Seeking Online versus Offline. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 37(4), 315-333. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228835.2019.1617823

Montenegro, M., Herrera Montenegro, L. C. y Torres-Lista, V. (2020). The rights of LGBTIQ + people, gender agenda and equality policies. Encuentros (Maracaibo), 11, 9-23. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3687275

Nijensohn, M. (2023). The radical politics of Judith Butler. A “turn towards the political”? Universality-to-come and precariou/s/ness. Las Torres De Lucca, 12(1), 53-64. https://doi.org/10.5209/ltdl.80926

Palacios Rodríguez, O. A. (2021). La teoría fundamentada: origen, supuestos y perspectivas. Intersticios Sociales, 22, 47-70. https://bit.ly/3OcTeWv

Pesquedua, P. (2023). Juegos de lenguaje que importan. La teoría de Judith Butler sobre la performatividad de género desde una perspectiva wittgensteiniana. El Lugar Sin Límites. Revista de Estudios y Políticas de Género, 5(8), 128-145. https://bit.ly/3VmN5LN

Pino Bermúdez, D. y Alfonso Gallegos, Y. (2011). Las teorías de la interacción social en los estudios sociológicos. Contribuciones a Las Ciencias Sociales. https://www.eumed.net/rev/cccss/14/pbag.html

Rivera-Martín, B., Martínez de Bartolomé Rincón, I. y López López, P. J. (2022). Hate speech towards LGTBIQ+ people: media and social audience. Revista Prisma Social, 39, 213-233. https://doi.org/10.2547/revist.8748

Rodríguez González, F. (2008). Diccionario gay-lésbico. Editorial Gredos.

Romo, G. (2023). De la clandestinidad a la luz, la lucha de la comunidad LGBT+ en Zacatecas. La Jornada Zacatecas. https://acortar.link/D8gsdf

Rovira, G. (2017). Activismo en red y multitudes conectadas. Comunicación y acción en la era del Internet. Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana.

Saez, V. (2024). Escritura literaria e identidad de género en la virtualidad: Relatos de vida de jóvenes en Instagram. Revista Argentina de Estudios de Juventud, 18, e082. https://doi.org/10.24215/18524907e082

Salín-Pascual, R. J. (2015). La diversidad sexo-genérica: Un punto de vista evolutivo. Salud mental, 38(2), 147-153. https://encr.pw/fslsv

Spargo, T. (2013). Foucalt y la teoría queer. Editorial Gedisa.

Strauss, A. y Corbin, J. (2002). Bases de la investigación cualitativa: técnicas y procedimientos para desarrollar la teoría fundamentada. https://shorturl.at/dhvLN

Trejo Olvera, N. (2022). La textura política de las imágenes, los cuerpos y los datos de la comunidad ballroom mexicana en Instagram. Educación Multidisciplinar para la igualdad de género, 4, 27-50. https://bit.ly/49ZvEFL

Torres Cruz, C. y Moreno Esparza, H. (2021). ¿Sociología cuir en México? Apuntes sobre las tensiones conceptuales para los estudios sociológicos de la sexualidad. Revista Interdisciplinaria de Estudios de Género de El Colegio de México, 7, 1-34. https://doi.org/10.24201/reg.v7i1.551

van Dijck, J. (2019). La cultura de la conectividad. Una historia crítica de las redes sociales. Editores siglo XXI.

Vázquez Parra, J. C. (2020). El género en perspectiva. 30 años de El Género en Disputa de Judith Butler. Revista Estudios, 40. https://doi.org/10.15517/re.v0i40.42018

Vega, A., Esquivel, D., Barrera, A. y Pacheco, C. (2024). La Violencia Sociodigital contra las Mujeres. Atlánticas. Revista Internacional de Estudios Feministas, 9(1),01-31. https://bit.ly/3IKVql5

Vives Varela, T. y Hamui Sutton, L. (2021). La codificación y categorización en la teoría fundamentada, un método para el análisis de los datos cualitativos. Investigación en educación médica, 40, 97-104. https://doi.org/10.22201/fm.20075057e.2021.40.21367

Winocur Iparraguirre, R. y Sánchez Martínez, J. A. (2015). Redes sociodigitales en México. Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Wodak, R. y Meyer, M. (2003). Métodos de análisis crítico del discurso. Editorial Gedisa. https://bit.ly/4alwEDE

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS, FUNDING AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Authors’ contributions:

Conceptualization: Chaparro-Medina Paola Margarita and Cervantes Hernández Rubén. Software: Cervantes Hernández Rubén. Validation: Chaparro-Medina Paola Margarita and Cervantes Hernández Rubén. Formal analysis: Chaparro-Medina Paola Margarita and Cervantes Hernández Rubén. Data curation: Chaparro-Medina Paola Margarita. Drafting-Preparation of the original draft: Chaparro-Medina Paola Margarita and Cervantes Hernández Rubén. Drafting-Revision and Editing: Chaparro-Medina Paola Margarita and Cervantes Hernández Rubén. Visualization: Cervantes Hernández Rubén. Supervision: Chaparro-Medina Paola Margarita and Cervantes Hernández Rubén. Project management: Chaparro-Medina Paola Margarita and Cervantes Hernández Rubén. All authors have read and accepted the published version of the manuscript: Chaparro-Medina Paola Margarita and Cervantes Hernández Rubén.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments: This text was created thinking of all young people of gender diversity who have lived under oppression.

Conflict of interest: none

AUTHORS:

Margarita Paola Chaparro-Medina

Autonomous University of Chihuahua.

Full-time research professor at the Autonomous University of Chihuahua (UACH). D. in Philosophy with emphasis in Cultural Studies from the Autonomous University of Nuevo León (UANL), Mexico. Master in Sociology from the University of Art and Social Sciences of Santiago de Chile (UARCIS). Diploma in Gender Studies and Feminist Theory from the Central University of Chile. Diploma in Liberal Arts from Adolfo Ibáñez University, Chile. Diploma in Qualitative Methods for Social Research, Diego Portales University, Chile. She is a member of the academic groups of the Master Degree in Educational Innovation and the Doctorate Degree in Education, Arts and Humanities of the UACH. She has a Prodep profile and she is a member of the National System of Researchers (candidate level).

Orcid ID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7270-9903

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=CNuSwkUAAAAJ&hl=es

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Paola-Chaparro-Medina

Rubén Cervantes Hernández

Inter-American University for Development, Zacatecas.

D. in Education, Arts and Humanities from the Autonomous University of Chihuahua, Master in Humanistic and Educational Research from the Autonomous University of Zacatecas and a specialist in Cultural Policies and Cultural Management from the Metropolitan Autonomous University. He is also a member of the National System of Researchers (candidate level).

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9390-9461

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?hl=es&user=A5z412sAAAAJ

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ruben-Cervantes-Hernandez

Academia.edu: https://uach-mx.academia.edu/RubenCervantesHernandez