Revista Latina de Comunicación Social. ISSN 1138-5820 / No. 82 1-19.

Access to the labour market in the digital society.

The use and assessment of employment websites

El acceso al mercado de trabajo en la sociedad digital. Uso y valoración de los portales de empleo en Internet

Manuel Martínez-Nicolás

Universidad Rey Juan Carlos. Spain.

manuel.martinez.nicolas@urjc.es

Beatriz Catalina-García

Universidad Rey Juan Carlos. Spain.

María del Carmen García-Galera

Universidad Rey Juan Carlos. Spain.

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The emergence of social networks and online job portals has changed the strategies for accessing the labour market. Although traditional channels continue to be perfectly valid options, such as job agencies, public employment services, corporate websites, personal contacts and others, current evidence suggests that the new digital channels, and specifically platforms that specialise in publishing job offers, are a preferred resource for employers and job seekers. Methodology: This paper analyses the methods used by Spanish adults in searching for employment, with special emphasis on the use and evaluation of digital job portals. To this end, a survey was designed for a representative sample of the population (N=673) between 25 and 54 years of age, who live in the Autonomous Region of Madrid. Results: Approximately 70% of those surveyed had at some point obtained employment through job offers posted on these portals, which confirms the hypothesis of widespread use of these platforms in searching for and finding work. Discussion and conclusions: The results confirm that there is no gender divide nor generation gap with regard to the use of these sites, success in obtaining a job, or the appraisal of digital job portals. Nevertheless, a significant education gap exists, which is probably linked to the lack of digital literacy among the population with low educational levels.

Keywords: Labour market; employment search; job portals; digital literacy; education gap; generation gap.

RESUMEN

Introducción: La irrupción de las redes sociales y de los portales de empleo en internet ha modificado las estrategias de acceso al mercado laboral. Aunque las vías tradicionales (empresas de recursos humanos, servicios públicos de empleo, páginas web corporativas, contactos personales, etc.) continúen siendo opciones perfectamente vigentes, la evidencia disponible indica que los nuevos canales digitales, y especialmente las plataformas especializadas en la publicación de ofertas de trabajo, son un recurso preferente para los empleadores y para los demandantes de empleo. Metodología: En este trabajo se analizan los métodos utilizados por la población adulta española para la búsqueda de empleo, incidiendo específicamente en el uso y la valoración que hacen de los portales digitales. Para ello se diseñó una encuesta a una muestra representativa (N=673) de la población de entre 25 y 54 años residente en la Comunidad de Madrid. Resultados: En torno al 70% de los encuestados obtuvo en alguna ocasión un puesto de trabajo a través de ofertas difundidas en estos portales, confirmando la hipótesis del recurso generalizado a estas plataformas para buscar y encontrar un empleo. Discusión y conclusiones: Los resultados no permiten sostener la existencia de brechas de género o generacionales en el uso, éxito laboral obtenido y valoración de los portales digitales, pero sí una significativa brecha educativa, probablemente vinculada a deficiencias en la alfabetización digital de la población con menor nivel de estudios.

Palabras clave: mercado laboral; búsqueda de empleo; portales de empleo; alfabetización digital; brecha educativa; brecha generacional.

1. INTRODUCTION

Although the concept of employability has been used in different contexts with different meanings (McQuaid & Lindsay, 2005), there is general agreement that having access to employment is a crucial factor in people's lives (Peeters et al., 2019). Definitions of employability converge in considering it the perception people have of their ability to obtain and keep a paying job throughout their working lives (Hillage & Pollard, 1998; Harvey, 2001; Fugate et al., 2004; Bridgstock, 2009; Cole & Tibby, 2013). Therefore, employability refers to a set of achievements, such as technical knowledge, professional skills, and personal attributes, which make individuals more likely to obtain, retain, or change jobs (Salvetti et al. 2015). Although it is undisputed that job success is linked to an individual’s level of education, the skills needed for the job search itself are irrelevant. Nevertheless, on many occasions knowledge and the effective use of job search methods or strategies has an impact on a person’s job opportunities (Fernández-Sánchez et al., 2014; Fernández-Izquierdo et al., 2018).

Digitisation has added further complexity to the situation. On the one hand, it has streamlined the job search process with the emergence of specific digital tools. The most notable instruments are job portals that specialise in publishing employment offers, although other non-specific channels are also used for this purpose, such as social networks. As companies and job seekers tend to interact in this environment, the chances of success in securing employment requires individuals to have an optimal level of digital literacy. Thus, the search for employment in the digital society requires a specific set of skills and practices that are increasingly necessary for people who are looking for a job, or for someone searching for a new job that might be better than the one they have.

To explore this situation, a survey was designed for a representative sample of the adult population between 25 and 54 years of age, who live in the Autonomous Region of Madrid (N=673). The purpose was to analyse the ways in which the labour market is currently accessed, the factors that might influence the job search strategies used by different sectors of the population, and the perceived degree of use, involvement, and utility of specialised online portals.

1.1. Access to the labour market in the digital society

The expansion of social networks and specialised digital platforms has affected the way job searches are carried out. They are considered a useful complement to traditional ways of accessing the labour market (Pais and Gandini, 2015). If personal relationships have traditionally been essential for this purpose, the digital transformation has made it necessary to be present on online job sites as well. The launch of portals such as LinkedIn and Infojobs, or even social networks such as Facebook, Twitter, and others, have allowed individuals to increase their employment opportunities by allowing them to create professional profiles and generate networks of contacts with other people (Boyd & Ellison, 2007). Frequent use of social networks is also associated with the so-called relational reconnection, or in other words, reconnecting with others after a prolonged period without contact, which allows individuals to expand their social capital and opportunities when seeking employment (Ramirez et al., 2017).

Wanberg et al. (2020) highlight significant differences between traditional players who might intervene in the job search process, such as family and friends (strong ties), and newer agents such as digital media (weak ties). Thus, although the use of the latter is likely to generate more job offers and interviews with potential employers, family and friends (personal relationships) obtain a larger number of job opportunities with a higher likelihood of success (Barbulescu, 2015; Obukhova, 2012). Updating this study, Garg and Telang (2018) also found that weak (digital) ties had a small impact on job opportunities, while strong (personal) ties generated more employment offers and interviews for job seekers.

Nevertheless, specialised internet platforms have become the standard for building virtual and personal networks in the professional realm (Peterson & Dover, 2014). The use of these platforms allows interaction with other people and the establishment of relationships that can lead to job opportunities. Among their advantages, Kuhn and Skuterud (2004) point out that they are relatively inexpensive, and they save time compared to traditional methods. In fact, Dillahunt et al. (2021) consider that online portals are now just as useful for work searches as a candidate’s own friendships or offline professional contacts. Gasparėnienė et al. (2021) even argue that these platforms have completely replaced traditional ways of searching for jobs, and that portals such as LinkedIn have paved the way with interactive CVs, which have made traditional letters of recommendation obsolete. Along the same lines, Oncina and Pérez-García (2020) assert that not using the Internet today to look for a job, or not knowing how to do it properly, are two of the main barriers to accessing the labour market and can even become a factor of exclusion from the workforce.

1.2. Digital success in the job search

In any case, there is still a lack of evidence regarding the specific impact of internet portals on the search for a job, or on the factors that have an impact on digital success in obtaining a job. The report entitled Talento Conectado [connected talent] (Infoempleo, 2019) reveals that the first option used by active job seekers is internet portals, which are utilised by 98% of those surveyed. This is followed by corporate websites (95%), recruitment agencies (93%), personal contacts (93%), and social networks, although to a far lesser extent (23%). In fact, according to data from the National Institute of Statistics, 628,000 people found a job in Spain in 2019 through the Internet, half of whom were between 16 and 34 years of age (González de Molina, 2019).

Nevertheless, the use of the new digital channels to successfully land a job is likely to be influenced by a number of factors, mainly socio-demographic. Dillahunt et al. (2021) analysed the situation of a sample of active job seekers (N=768) and found a certain degree of correlation between specific characteristics of individuals (income, gender, years of education, and even ethnicity) and the use of specialised online platforms.

Thus, people with higher incomes who searched for jobs on digital portals were more likely to receive return calls than those with lower incomes. Mowbray and Hall (2020) analysed the role of social networks in young people's job searches and found that Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn were the most commonly used for this purpose. Moreover, the type of job sought influenced the online behaviour of users as well. The Eurostat barometer (2019) shows that 29% of young Europeans aged 16-29 use the Internet to look for a job or to respond to a job offer, while only 16% of adults do so for this purpose. The Nordic countries were among the top performers, with Finland leading the way, where more than 50% of young people use the digital environment to search for a job. Spain ranked ninth, with 33% of young people and 18% of adults using the Internet for this purpose.

Michavila et al. (2016) analysed the methods used to look for a job by university graduates in Spain, and found that nearly half of them (47.9%) relied on direct personal contacts, yet a similar percentage (45.7%) did so by responding to offers they already knew about due to the use of specialised portals. In addition, graduates used corporate websites and social media more than more traditional channels, such as temporary job agencies, recruitment agencies, and newspaper advertisements. In line with the findings of other research, searching for a job on digital media is not an alternative, but rather a complement to more traditional ways of looking for employment (Karácsony et al., 2020).

In any case, it is not necessary to be out of the labour market and looking for a job in order to have a job profile (career, educational background, etc.) on digital media. A recent study by the specialised portal known as Infojobs (2022) reveals that 60% of employees have a professional account on this platform. Some 40% have a LinkedIn profile and, although with lower percentages, social media is also used for job searches, including Facebook (26%), Instagram (21%) and X (14%). Especially noteworthy is the strong presence of young people aged 16-24 on channels not directly associated with the search for work, such as Instagram (37%), Twitter (21%), YouTube (16%), and even TikTok (18%). By contrast, older respondents with more experience in the workforce, aged 55-65, are the least likely to use social media and internet sites. In fact, just over half admit to not having any work profiles on these platforms.

2. RESEARCH QUESTIONS

This research analyses the strategies used by the Spanish adult population in searching for and finding paid jobs. The starting hypothesis is that websites specialising in the publication of job offers are the preferred means of accessing the labour market, given the widespread digital literacy of the Spanish population, the availability of multiple specialised platforms, and the widespread use of these sites by employers and job seekers. Within this general framework, the following research questions are posed:

RQ1. What channels do Spanish adults use to look for jobs?

RQ2. To what extent do Spanish adults perceive internet portals to be an effective resource for seeking and finding a job?

RQ3. What is the degree of involvement, trust, and expectations of those who upload personal information related to employment to these platforms, such as education, experience, professional background, etc.?

RQ4. Apart from the implications of the previous question, how do individuals who are registered on these sites rate the usefulness of these platforms for landing a job?

RQ5. Considering the target population, have any differences been observed in the ways of accessing the labour market, the involvement in job portals, the assessment of their usefulness, etc., based on socio-demographic variables (gender, age, and educational levels) and employment variables (years of work experience)?

3. METHODOLGY

To answer these questions, a survey was carried out with 673 people living in the Autonomous Region of Madrid, between 25 and 54 years of age. A stratified probability sample was designed with random selection of the final sample units. The error for the sample as a whole was ± 2.67%, with a confidence interval of 95%.

For this paper, the range of 25 to 54 years of age is what the authors consider to be the adult population. These age parameters allowed for the collection of information on those individuals who had already completed their studies in the field of higher education. For analytical purposes, this population was segmented into three categories: 25-34 years old (young workers); 35-44 (middle-aged workers); and 45-54 (older workers). Although it is not accurately defined, these three categories can be associated with the generations identified as millennials, generation X, and boomers (Díaz-Sarmiento et al., 2017), who are often addressed in works about digital literacy (Vasilescu et al., 2020; Salamanca & Sagredo, 2022).

The questionnaire was conducted online through the survey company known as 40dB. Among the advantages of online surveys, Evans and Mathur (2018) point out the efficiency in the collection of information (speed, suitability for statistical processing, etc.), ease of defining the sample, an increase in the response rate, and an obvious cost reduction in obtaining a representative sample. To determine the degree of dependence of the variables related to the use and evaluation of internet portals, with regard to the independent variables of gender, age, education levels, and work experience, the non-parametric Pearson's chi-square statistical test (χ2) was applied with a value of 0.05.

The characteristics of its job market and the use of the internet for specific work-related reasons justify the relevance of observing the use and assessment of digital job portals in the Region of Madrid. Benefiting from the so-called ‘capital effect’ exerted by the city of Madrid, Pérez and Reig (2020, p. 7) consider that the Community of Madrid has been configured as a “motor for the country growing as a whole [Spain]” in recent decades, a gateway for significant connections with the outside world in many areas ˗economic, technological, and in general, new knowledge˗ and as a high purchasing power market in continuous expansion. The Region of Madrid is the Spanish region with the highest concentration of public and private companies, which would explain the dynamism of the Madrid job market. In 2022, the community recorded an activity rate (percentage of the population between 16 and 54 years old who are actively working) of nearly 80%, the highest among Spanish regions, and an employment rate (percentage of the population of working age effectively employed) of close to 60%, only a few tenths behind the Baleares Islands (Serrano et al., 2023, pp. 28-29).

In terms of internet penetration and usage, over 95% of the Spanish population were regular users (in the last three months) of online products and services in 2023 (INE, 2024). There were no significant differences in percentages across various autonomous communities and cities in Spain, ranging from 99.3% in the city of Melilla to 90.9% in the Extremadura region (Statista, 2024). Consequently, the most reliable indicator for the purpose of this study would be specifically work-related internet usage. Although the data in this regard are somewhat imprecise, they suggest that Madrid and Catalonia are the Spanish regions with the highest number of profiles on professional social networks (Infojobs, 2022). Trends related to the use and assessment of job portals observed in the Community of Madrid would therefore be representative of regional labour markets in Spain with similar development (especially in Catalonia, the Basque Country, and the Valencian Community), providing insights into the behavior that might occur in the evolution of other labour markets.

4. ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

4.1. Paths used to access the labour market

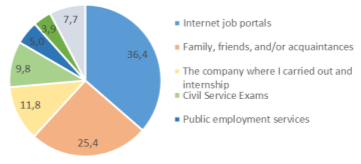

The ways of learning about employment offers and landing a job are extremely varied (up to ten options are included in the Other category in Figure 1), yet the majority of the sample surveyed accessed the job market either through advertisements published on internet portals (mainly Infojobs, LinkedIn, Infoempleo and Buscojobs), or through their network of personal relationships (family, friends, acquaintances, etc.).

When asked how they had found their last job, nearly 40% of the respondents (N=628) said they had done so by applying for jobs found on these platforms, although 25% used personal contacts. Therefore, social relationships are still a very effective resource for securing a job in the Spanish labour market.

Figure 1: Paths used to access the most recent job (%).

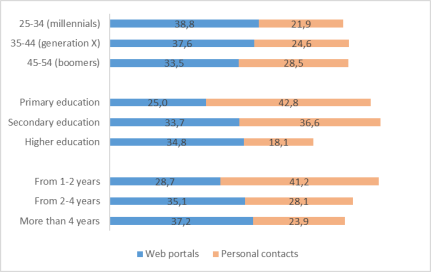

The use of Internet portals and personal contacts assisted over 60% of the respondents in obtaining their last job. Differences in the use of any of the channels are not significant with regard to gender (χ2 = 0.085), yet they are significant regarding age (χ2 = 0.013), educational level (χ2 = 0.001) and, to a lesser extent, years of experience in the job market (χ2 = 0.004) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Access to the most recent job according to age, educational level, and work experience (%).

Source: Own elaboration.

As previously mentioned, age shows slight differences and should be analysed together with data related to work experience, bearing in mind that generally speaking, the older a person is, the greater the probability of remaining in the labour market. It has also been observed that as age increases, the percentage of those who obtained their last job through offers posted on websites decreases and, nearly in the same proportion, the percentage of those who obtained their last job through personal contacts increases.

Initially, this pattern could be attributed to an assumed generation gap in the digital literacy of the population, in which case the younger age groups (millennials and generation X) might be more willing, competent, or confident in using the web to interact with the world, and also to search for and obtain employment.

However, if we look at the number of years in the labour market, a paradox can be observed: among the group with more years of work experience, the percentage of those who accessed their last job through internet offers is higher, with a lower use of personal contacts.

In addition, more than 40% of those who have been in the labour market for only 1 or 2 years, and nearly 30% of those who have been in the job market for 2 to 4 years, obtained their last job through contacts (family, friends, acquaintances, etc.), a percentage that decreases to 24% among those with a longer job history (more than 4 years). Therefore, it is possible that having a good network of social relations continues to be the most effective way of obtaining one’s first job, or the first series of jobs, and that people turn to internet offers when they have achieved a certain degree of permanence or job stability, either in searching for better working conditions, a better match with their professional profile, or simply when they want to change jobs.

Looking at the effect of education, Figure 2 shows that the highest level of reliance on personal contacts is found among respondents with only primary education, with more than 40% having obtained their last job through personal contacts. This percentage decreases somewhat (around 35%) among the population with secondary education and falls below 20% for those with higher education. The possible impact on job search strategies based on differences in digital literacy should, therefore, not be ruled out, although it might not be a result of the generation gap, but rather of an educational gap between different levels of formal education, which would place the population with fewer educational resources at a disadvantage when it comes to taking advantage of the digital environment to search for and find a job.

4.2. Use of digital job portals

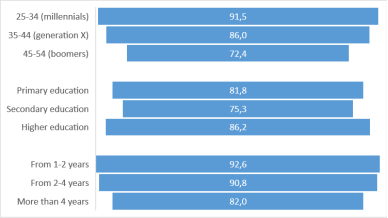

Regardless of whether users are successful in obtaining a job through online portals, the confidence or expectation that digital platforms are an effective resource for this purpose seems to be widespread among the adult population. A high percentage of respondents (82.5%) say they are registered on one of these portals, mostly on Infojobs (62.5%) and LinkedIn (52.9%). There are no significant differences between women and men in this behaviour pattern, with χ2 values well above 0.05 (82.5% of women and 82.4% of men are registered on a job portal), nor between sectors of the population with different educational levels (Figure 3). Thus, the results indicate that there is no significant education gap in terms of the confidence or expectation of finding a job through these portals, although there appears to be a generation gap (χ2=0.001), largely associated with years of work experience (χ2=0.015).

Figure 3. Population with an account on a job portal according to age, educational level, and work experience (%).

Source: Own elaboration.

In fact, the percentage of those registered on a job portal among the younger age groups (around 90% of millennials and generation X) is much higher than those who are registered among the older age groups (just over 70% of boomers). However, this does not necessarily indicate a generation gap in terms of skills and attitudes with regard to the digital environment, as these differences could be due to the lower incentive for the older population to register on job portals, possibly because they are more stable in the labour market in terms of working conditions and professional background. As such, they may have fewer expectations and less need to change jobs.

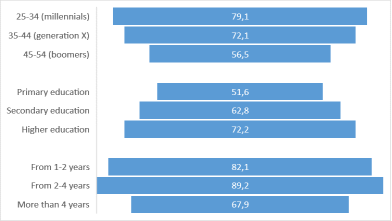

Although some differences exist, the same pattern can be observed in the success of the adult population in accessing the labour market through job offers published on these platforms. Although the percentage of those who obtained their last job through these portals is around 40%, only 31.8% say they have never found a job on these platforms. In other words, around two thirds of the respondents (nearly 70%) would have obtained a job at some point through internet offers, with no significant differences between women and men (68.3% and 68.1%, respectively; χ2=0.07). Regarding age and work experience, although the statistical coefficients indicate a slight variation, the percentages suggest that these differences are merely circumstantial, as it will be explained below. On the other hand, the education gap does appear to be a confirmed factor that influences the use of internet portals to find a job (χ2=0.04).

Figure 4. Access to a job at some point through internet portals, according to age, educational level, and work experience (%).

Source: Own elaboration.

As seen in Figure 4, the breakdown of the percentages of those who have obtained a job at some point through online portals shows a similar pattern among the different groups according to age and work experience. In both cases, respondents from the youngest sectors (millennials and generation X), with fewer years in the job market (from 1-2 and 2-4 years), displayed similar percentages and distances from those of the oldest group (boomers), and the most experienced workers (more than 4 years). As previously noted, the differences between age groups do not necessarily indicate a generation gap in digital literacy, and may be due to circumstantial factors, such as the very existence of these channels, the spread of their use by employers, or improved usability for jobseekers, which would enhance the chances of finding a job in this way among the younger generations. The same applies to differences in work experience, which is a factor that is largely associated with age.

On the other hand, the level of education seems to be a variable with a strong impact on the possibility of obtaining a job through the digital environment. As the educational level of the respondents increases, the percentage of job success regarding offers advertised on these platforms increases by 10% as one moves up the educational ladder. Slightly more than half of those with only primary education got a job through this channel at some point in their work history, yet the percentages rise to more than 60% and 70%, respectively, for those with secondary and higher education. This finding is consistent with the results obtained regarding the access pathway to one’s last (Figure 2), which reinforces the possibility that there is an education gap in the use of new digital channels in the labour market.

4.3. Engagement with digital job portals

Registration on one or more online platforms is necessary for accessing the job offers posted on those sites, yet success in obtaining a job also depends on the degree of involvement, or trust, in these portals. Such engagement is defined, among other behavioural patterns, by the frequency with which the portals are consulted, as well as the number of times job seekers update their personal information (education, career path, interests, etc.) in their accounts on these platforms.

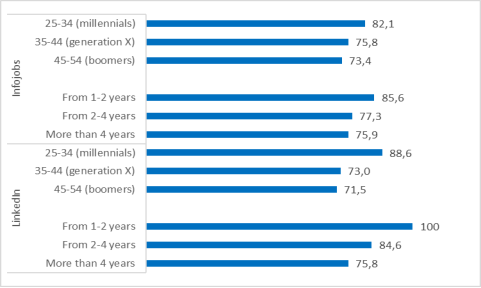

Regarding the two portals with the highest percentage of registrations (Infojobs and LinkedIn), users are highly confident that they will find an attractive job offer on these sites. If we consider a high frequency of consultation to be at least once a week, the average percentage of the respondents (N=590) who check these two portals with this frequency is nearly 60% (55.7% of those registered on Infojobs and 63.2% of those with a LinkedIn account). This level of involvement does not differ according to gender and age (χ2 >0.05), yet differences have been observed according to educational levels (χ2=0.048) and, above all, years of work experience (χ2=0.017) (Figure 5). With slight differences between portals, the more years of work experience, the lower the frequency of using these platforms. Undoubtedly, an opposite pattern of behaviour would have been anomalous because people who have entered the job market more recently (between 1 and 2 years in the workplace) are more likely to search for new jobs and, consequently, they consult job offers on these platforms more frequently.

Figure 5. Consultation frequency of employment offers on job portals, according to work experience (%).

Source: Own elaboration.

What is more important than a mere consultation is the frequency with which users update job-related information on their personal accounts. Respondents had a choice of three possible answers; “When I have something new to include”; “Occasionally”; and “I don't usually update it”. Data for the first two answers indicate that around 75% of respondents actively and regularly update their job profiles, with no significant differences according to gender (an average percentage for Infojobs and LinkedIn of 74.9% among women and 78.9% among men), nor educational levels (an average of 74.6% among those with primary education, 73.3% for those with secondary education, and 77.6% for those with higher education). However, the differences according to age (χ2=0.008) and years of work experience (χ2=0.002) are statistically significant (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Frequency with which work profiles are updated on job portals, according to age and work experience (%).

Source: Own elaboration.

Regarding frequency of consultation, the population groups with fewer years of work experience, who are clearly associated with the age variable, are the ones who regularly update their profiles. The more proactive attitude of the younger generations (millennials) in keeping this information up to date (between 10 and 20 points above the percentage of boomers, according to the portal) is not related to an assumed higher level of competence or willingness to use these digital tools compared to the older population. The authors assert that this tendency could be due to a circumstantial factor involving the personal situation of young people in which access to the labour market is a high priority which, among many other factors, might lead this sector to place greater emphasis on displaying themselves in the best possible light in the employment showcase of online job portals.

4.4. Assessing the usefulness of digital job portals

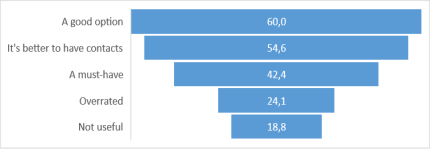

A high percentage of the Spanish adult population registered on job portals (more than 80% of the respondents) have found a job at some point through this channel (almost 70%), regularly consult job offers on these sites (around 60% at least once a week) and keep their job profile updated (around 75%). These data indicate that digital platforms have become not only common, but also a very efficient resource in job search strategies for nearly all sectors of the population. An additional piece of information in this regard is the general assessment made by respondents of the usefulness of such sites in finding a job (Figure 7). Some 60% consider them to be “a good place to make myself known and publish my CV” (“It’s a good option”), and more than 40% think they are “a must-have for finding a job nowadays”. Nevertheless, more than half of those surveyed believe that “the best offers tend to come through personal contacts”, and even a sizeable proportion (20%) stated unequivocally that "they are not really useful for finding a job”.

Figure 7. Perception of the usefulness of internet portals for finding jobs (%).

Source: Own elaboration.

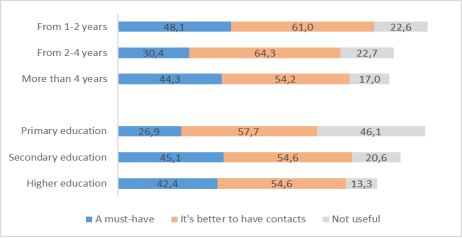

To determine the influence of factors related to both socio-demographics and work experience on the perception of the usefulness of these portals, an analysis was carried out that specifically focused on the distribution of responses to the three most opposed options: that these portals are essential for finding a job; that they are not useful for this purpose; and having contacts is a better option. No significant differences were observed according to gender and age, with statistical values above 0.05 in both cases, yet there were differences based on years of work experience (with χ2 values ranging from 0.023 to 0.044) and educational levels (with χ2 values ranging from 0.001 to 0.013) (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Perception of the usefulness of job portals, according to work experience and educational level (%).

Source: Own elaboration.

The perceived usefulness of job portals according to each individual's work history might appear somewhat counterintuitive. At a higher percentage, respondents who have been in the workforce the shortest period (1-2 years) consider digital platforms to be indispensable, yet they are also the group with a higher percentage of conviction that having personal contacts is a better option (more than 60%), or they see these sites as not useful (more than 20%). A very similar pattern is found among the population with 2 to 4 years of experience in the labour market, with the exception that these portals are considered essential. This viewpoint contrasts with that of the sector with more work experience (more than 4 years). Older workers share the same opinion as entry-level workers, both of whom consider job portals to be essential, yet the former are the least likely to rely on personal contacts (only around 50%), and the most reluctant to believe that these sites are not useful for finding a job.

The fact that the sectors of the population with less work experience (1-2 years), and those with more (4 years and above) are the ones who consider these portals to be crucial for finding a job today might indicate the role of these platforms at two specific points in an individual's work history: entering the labour market to obtain one's first job(s); and the change of jobs to improve working conditions, to match one's own professional profile, or to re-enter the workforce after a job loss. The first situation is common among the population with a shorter employment history; the second is typical of those who have been in the workforce a number of years. This also helps to explain why the older population is precisely the least likely to rely on personal contacts to change jobs or re-enter the labour market, and the most reluctant to state that these portals are not useful for finding a job.

Regarding the influence of educational levels, the results are more clear-cut and consistent with the recurrent findings of this study. Thus, we can see in Figure 8 that with the exception of subtle differences, the perception that job portals are essential, or that they are not useful, increases or decreases, respectively, as the level of education of the respondents increases. People with only a primary school education hardly consider them essential (only a quarter of this sector of the population), and nearly half of them believe they are not useful for finding a job. This is also the group with greater expectations from personal contacts (nearly 60%) than from the offers they might find on the Internet (around 25%), which indicates that the education gap previously observed is related to the differential use of the digital environment depending on the educational level of the individual.

In any case, the perception that personal contacts are more effective for obtaining a job than using internet offers is similar among individuals with different educational levels (just three percentage points difference). The reliance on job offers published on digital portals, which by its very nature is open to all interested candidates, is widespread among the Spanish adult population. Nevertheless, the traditional idea that the best option is to have good contacts, in order to avoid the uncertainty of engaging in competition that is open to the merits of each individual with regard to training, professional experience, suitability for the tasks required, etc., is also widespread.

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, we have analysed the methods and strategies used by the Spanish adult population for accessing the labour market, specifically focusing on the use and evaluation of internet job portals, based on a sample of people living at the Region of Madrid. The findings confirm the hypothesis that these web-based platforms are currently the preferred way to find employment. Nearly 70% of the respondents indicate that they have obtained a job through these digital portals at some point in their career, and 40% obtained their last job through these platforms.

These results are in line with previous research on the predominance of the internet, including specialised portals and social media, in the process of finding and obtaining a job, although the traditional method of personal contacts is still a common way of entering the workforce as well (Obukhova, 2012; Barbulescu, 2015; Garg & Telang, 2018). In fact, despite the use of social relations to secure employment, which is around 25% with regard to the most recently obtained job, more than half of the respondents consider that when it comes to accessing the labour market, “the best thing” is to have personal contacts. There was broad consensus on this issue among the adult population surveyed, regardless of socio-demographic factors (gender, age, and educational levels) and work experience (number of years in the workforce).

What is striking is the uniformity of importance placed on personal contacts by the population groups with different educational levels. Although the use or need for these contacts increases as the level of formal education decreases (around 43% of the respondents with only primary education obtained their last job in this way, compared to 18% of those with higher education), the perception that this is “the best” way to get a job is highly homogeneous, with a difference of only three percentage points between the population with primary education (57.7%), and those with secondary and higher education (54.6% in both cases). The high value placed on relational capital in obtaining employment is not an anomaly attributable to the unique cultural characteristics of a given society (in this case, Spain). Instead, it is a widely-used resource, specifically confirmed by the work of Pais and Gandini (2015).

The performance indicators of job success, commitment, and confidence of the adult population in job portals do not indicate gender and generational gaps in the use of these tools. Regarding the first point, the results of this study would align with those obtained by the National Observatory of Technology and Society (ONTSI) in a recent study on the global digital competencies of the Spanish population. These competencies are only slightly higher in men compared to women. For instance, 26.3% of the male population would have basic digital competencies, while 25.6% of the female population would have the same. Additionally, 39.4% of men would have advanced digital competencies, compared to 37% of women (ONTSI, 2023, p. 17). However, the same report highlights significant differences based on age. 80% of the population between 25 and 34 years old (millennials, in this study) demonstrate basic or advanced digital competencies. This percentage gradually decreases as age increases: 75% in the 35 to 44 age group (Generation X) and 66% in the 45 to 54 age group (baby boomers) (ONTSI, 2023, p. 19).

However, the differences in the use and assessment of job platforms among diverse age groups observed in this research cannot necessarily be explained by assumed differences in the degree of digital literacy, which is seen as optimal for younger workers and deficient for older ones. Instead, it could be due to the different life situations of each group. Due to the fact that older people entered the labour market before digitisation was introduced into the job search process, or that the employment of this group is more stable as a result of years of experience and job matching, this could explain the lower use and dependency on internet offers by the older sector of the population. The results obtained by Dillahunt et al. (2021: 10) regarding the influence of these two factors (gender and age) on the use of internet tools for job searching in the United States are also inconclusive in this regard. They merely point out that “men and younger adults tend to use digital platforms more often in general”.

Dillahunt et al. (2021, p. 10) do, however, note a differential impact based on income level and formal education, which “were strongly correlated with the frequency of using digital platforms for job search”, higher among individuals with more income and education ˗factors that are often linked. In the same vein, many of the indicators in this paper provide evidence of an educational gap in the use and assessment of the utility of these tools for job searching. Respondents with the lowest educational level (only primary school) are the least successful in finding a job through internet portals throughout their working lives, and the most likely to doubt the usefulness of such sites for this purpose.

As it is possible that the offers published on these platforms come mainly from productive sectors that require mid to high levels of education, this might limit the job opportunities for the sector of the population with a low educational level who use these channels. Nor can it be ruled out that the public nature of these offers, which are open to the free competition of applicants, reduces the options available to the population with fewer educational resources, who would therefore be more dependent on personal contacts.

Nevertheless, it is also possible that this educational gap is an indication of certain deficiencies in the digital literacy of the less educated population, as observed in the report by the National Observatory of Technology and Society (ONTSI) (2023) on the digital competencies of the Spanish population. Along with age, and well above other sociodemographic factors considered (gender, employment status, and place of residence), the level of education generates the greatest differences in the acquisition of basic or advanced digital competencies. 85% of those with higher education and 73% with secondary education demonstrate this basic or advanced level of digital competency, while only 38% of individuals with only primary education or no education achieve the same level. This represents a 47-point difference between population groups with varying degrees of digital literacy (ONTSI, 2023, p. 22)”

In terms of strictly using online job portals, this study observes that this demographic segment with lower education levels maintains professional accounts on job portals at levels that are similar to those of candidates with more education, it would not seem reasonable to argue that the low rate of employment success in using these channels, or the perception of its limited usefulness, are related to an assumed deficit in digital literacy, yet the possibility cannot be ruled out. Success in obtaining employment through internet job portals requires not only those candidates be present on these sites. They also need specific communication skills in order to navigate in this environment, such as the ability to use audio-visual technology. As can be expected, this particular skill is generally scarce among the population with a low level of education. Consequently, even if the people in this group have a digital presence on job sites, they are not likely to be in a position to effectively increase their employment opportunities through these platforms.

If success in today’s economic systems and job markets depends, even at a basic level, on strategies for job searching that require at least basic digital competencies, the results of this study indicate that the digital literacy deficit among the population segment with lower educational levels places them in a potential situation of labor exclusion, as warned by Oncina and Pérez-García (2020). The Spanish Government’s Digital Agenda 2025 includes a Digital Skills National Plan, which will invest over €3.5 billion between 2021 and 2025, with the expectation that “80% of the Spanish population will receive training in digital competencies” (Gobierno de España, 2023, p. 2). The budget allocated for digital skills training for employment will absorb more than a third of this investment (34.9%), second only to the allocation for educational purposes (39.2%)

The plan includes among its objectives to “guarantee” the acquisition of advanced digital competencies for both the unemployed population, to improve their employability conditions, and the employed population, enabling them to adapt to digital transformation and the automation of the economy (Gobierno de España, 2023, p. 5). Addressing a fundamental employability factor —the ability to search for jobs using specialized internet portals— the results of this study indicate that the primary digital literacy gap to close is educational. This gap leaves the population with lower educational levels in a vulnerable situation in an increasingly digitized job market, even at the basic level of job search strategies.

6. REFERENCES

Barbulescu, R. (2015). The strength of many kinds of ties: unpacking the role of social contacts across stages of the job search process. Organization Science, 26(4), 1040-1058. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2015.0978

Boyd, D. M. y Ellison, N. B. (2007). Social network sites: definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 13(1), 210-230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x

Bridgstock, R. (2009). The graduate attributes we’ve overlooked: Enhancing graduate employability through career management skills. Higher Education Research & Development, 28(1), 31-44. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360802444347

Cole, D. y Tibby, M. (2013). Defining and developing your approach to employability. A framework for higher education institutions. The Higher Education Academy.

Díaz-Sarmiento, C., López-Lambraño, M. y Roncallo, L. (2017). Entendiendo las generaciones: una revisión del concepto, clasificación y características distintivas de los baby boomers, X y millennials. Revista Clío-América, 22, 188-204. http://doi.org/10.21676/23897848.2440

Dillahunt, T. R., Israni, A., Jiahong, A., Cai, M. y Chiao-Yin, J. (2021). Examining the use of online platforms for employment: A survey of U.S. job seekers. Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. https://doi.org/10.1145/3411764.3445350

Eurostat (2019). People who used the Internet for job search or sending an application. https://bit.ly/49zggQD

Evans, J. R. y Mathur, A. (2018). The value of online surveys: A look back and a look ahead. Internet Research, 15(2), 195-219. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-03-2018-0089

Fernández-Izquierdo, A., Pastor, M. C. y Cifre, E. (2018). Estrategias de búsqueda de empleo en jóvenes: ¿existe diferencias de género?. Ágora de Salut, 5, 187-191. http://dx.doi.org/10.6035/AgoraSalut.2018.5.20

Fernández-Sánchez, J. A., De Juana, S., Manresa, E., Sabater, V. y Valdés, J. (2014). Métodos para la búsqueda de empleo. Universidad de Alicante.

Fugate, M., Kinicki, A. J. y Ashforth, B. E. (2004). Employability: A psycho-social construct, its dimensions, and applications. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65(1), 14-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2003.10.005

Garg, R. y Telang, R. (2018). To be or not to be linked: online social networks and job search by unemployed workforce. Management Science, 64(8), 3469-3470. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2017.2784

Gasparėnienė, L., Matulienė, S. y Žemaitis, E. (2021). Opportunities of job search through social media platforms and its development in Lithuania. Business: Theory and Practice, 22(2), 330-339. https://doi.org/10.3846/btp.2021.11055

Gobierno de España (2023). Plan de Recuperación, Transformación y Resiliencia. Componente 19: Plan Nacional de Capacidades Digitales. Unión Europea. NextGenerationUE. https://bit.ly/3W7mBhG

González-de-Molina, I. (2019). Más de 628.000 personas hallan un trabajo por alguna página web o app. La Razón. https://bit.ly/46eGV28

Harvey, L. (2001). Defining and measuring employability. Quality in Higher Education, 7(2), 97-109. https://doi.org/10.1080/1353832012005999

Hillage, J. y Pollard, E. (1998). Employability: Developing a framework for policy analysis. Research Brief, 85. Department for Education and Employment. https://bit.ly/47uXbgz

INE [Instituto Nacional de Estadística] (2024). Población que usa Internet (en los últimos tres meses). https://bit.ly/3vRUY1J

Infoempleo (2019). Talento conectado. Nuevas realidades en el mercado del trabajo. Infoempleo y EY Building a better working world. https://bit.ly/47xIidr

Infojobs (2022). Casi 6 de cada 10 empresas consultan las redes sociales de una persona antes de contratarla. Infojobs. https://bit.ly/3ugJ7cb

Karácsony, P., Izsák, T. y Vasa, L. (2020). Attitudes of Z generations to job searching through social media. Economics and Sociology, 13(4). https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2020/13-4/14

Kuhn, P. y Skuterud, M. (2004). Internet job search and unemployment durations. American Economic Review, 94(1), 218-232. https://doi.org/10.1257/000282804322970779

McQuaid, R. W. y Lindsay, C. D. (2005). The concept of employability. Urban Studies, 42(2), 197-219. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098042000316100

Michavila, F., Martínez, J. M., Martín-González, M., García-Peñalvo, F. J. y Cruz, J. (2016). Barómetro de empleabilidad y empleo de los universitarios en España, 2015. Observatorio de Empleabilidad y Empleo Universitarios. https://bit.ly/47H3ZYK

Mowbray, J. y Hall, H. (2020). Networking as an information behaviour during job search: A study of active jobseekers in the Scottish youth labour market. Journal of Documentation, 76(2), 424-439. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-05-2019-0086

Obukhova, E. (2012). Motivation versus relevance: Using strong ties to find a job in urban China. Social Science Research, 41(3), 570-580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2011.12.010

Oncina, L. y Pérez-García, Á. (2020). Patrones de búsqueda de empleo en Internet. Diagnóstico y retos de las personas en desempleo. Fundación Santa María la Real. https://bit.ly/47wUtHC

ONTSI [Observatorio Nacional de Tecnología y Sociedad] (2023). Colección Monográficos España Digital 2023. Competencias digitales. ONTSI (Ministerio para la Transformación Digital y de la Función Pública). https://bit.ly/3xLoUgs

Pais, I. y Gandini, A. (2015). Looking for a job online: An international survey on social recruiting. Sociologia del Lavoro, 137, 115-129. https://doi.org/10.3280/SL2015-137007

Peeters, E., Nelissen, J., De Cuyper, N., Forrier, A., Verbruggen, M. y De Witte, H. (2019). Employability capital: A conceptual framework tested through expert analysis. Journal of Career Development, 46(2), 79-93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845317731865

Pérez, F. y Reig, E. (2020). Madrid: capitalidad, economía del conocimiento y competencia fiscal. Instituto Valenciano de Investigaciones Económicas (Ivie). https://bit.ly/3xM0pjj

Peterson, R. M. y Dover, H. F. (2014). Building student networks with LinkedIn: The potential for connections, internships, and jobs. Marketing Education Review, 24(1), 15-20. https://acortar.link/hTyrxc

Ramirez Jr., A., Sumner, E. M. y Spinda, J. (2017). The relational reconnection function of social network sites. New Media & Society, 19(6), 807-825. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815614199

Salamanca, I. y Sagredo, E. (2022). Diversidad generacional y patrón de uso de Tecnologías de Información y Comunicación. RISTI. Revista Ibérica de Sistemas e Tecnologias de Informação, 47, 70-86. http://doi.org/10.17013/risti.47.70–86

Salvetti, F., La Rosa, M. y Bertagni, B. (2015). Employability. Knowledge, skills and abilities for the “glocal” world: Foreword. Sociologia del Lavoro, 137, 7-13. https://doi.org/10.3280/SL2015-137001

Serrano, L., Soler, Á. y Pascual, F. (2023). La calidad del empleo en España y sus comunidades autónomas. Fundación Ramón Areces. https://bit.ly/3Jqo3UY

Statista (2024). Porcentaje de usuarios de Internet en los últimos tres meses en España en 2023, por comunidad autónoma. https://bit.ly/3U6mvoa

Vasilescu, M. D., Serban, A. C., Dimian, G. C., Aceleanu, M. I. y Picatoste, X. (2020). Digital divide, skills, and perceptions on digitalisation in the European Union. Towards a smart labour market. Plos One. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232032

Wanberg, C. R., Ali, A. A. y Borbala, C. (2020). Job seeking: The process and experience of looking for a job. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 7, 315-337. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012119- 044939

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS, FUNDING AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors' contributions:

Conceptualization: Martínez-Nicolás, Manuel; Catalina-García, Beatriz; García-Galera, María del Carmen. Software: Not applicable. Validation: Martínez-Nicolás, Manuel; Catalina-García, Beatriz; García-Galera, María del Carmen. Formal analysis: Martínez-Nicolás, Manuel; Catalina-García, Beatriz; García-Galera, María del Carmen. Data curation: Martínez-Nicolás, Manuel; Catalina-García, Beatriz. Writing-Preparation of the original draft: Martínez-Nicolás, Manuel; Catalina-García, Beatriz; García-Galera, María del Carmen. Writing-Revision and Editing: Martínez-Nicolás, Manuel. Visualization: Martínez-Nicolás, Manuel. Supervision: Catalina-García, Beatriz. Project Management: García-Galera, María del Carmen and Martínez-Nicolás, Manuel. All authors have read and accepted the published version of the manuscript: Martínez-Nicolás, Manuel; Catalina-García, Beatriz; García-Galera, María del Carmen.

Funding: This work is the result of the collaboration between the research projects "New scenarios of digital vulnerability: media literacy for an inclusive society" (PROVULDIG2-CM), funded by the Community of Madrid and the European Social Fund (H2019/HUM-5775), and "Employability and entrepreneurship in Communication in the digital context: labor market demands, university training offer and work experience of graduates", funded by the State Plan for R+D+i of the Government of Spain (PID2019-106299GB-I00) (AEI/10. 13039/501100011033

AUTHOR/S/ES/AS:

Manuel Martínez-Nicolás

Universidad Rey Juan Carlos.

Professor at the Universities Autónoma de Barcelona (1990-1996), Santiago de Compostela (1996-2003) and, since 2003, at the Universidad Rey Juan Carlos. He is a member of the Advanced Communication Studies Group, and professor in the Master in Applied Communication Research (URJC). He has been director of the Working Group on History of Communication Research of the Spanish Association of Communication Research (2015-2024), and principal investigator in two projects funded by the State Plan for R+D+i. In the last 10 years he has published about thirty papers in scientific journals (Profesional de la Información, Communication & Society, Revista Internacional de Sociología, Política y Sociedad, Empiria, Telos, Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, among others), and in collective books.

manuel.martinez.nicolas@urjc.es

Índice H: 21

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3949-2351

Scopus ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=55135925700

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=7cc-OLIAAAAJ&hl=es

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Manuel_Martinez_Nicolas

Academia.edu: https://independent.academia.edu/ManuelMartínezNicolás

Beatriz Catalina-García

Universidad Rey Juan Carlos.

Professor of the Department of Journalism and Corporate Communication at the Universidad Rey Juan Carlos. PhD in Communication Sciences from Universidad Rey Juan Carlos (2011), Degree in Journalism from UCM (1989), and Degree in Political Science from UNED (2014). She has participated in several competitive projects. She is currently a research member of the National R+D+i Project "Repertorios y prácticas mediáticas en la adolescencia y la juventud: usos, ciberbienestar y vulnerabilidades digitales en redes sociales" (2023-2027). His lines of research are related to Audiences, Digital Communication and Opportunities and risks on the Internet. He has published more than 40 scientific articles in impact journals and more than a dozen book chapters. He has been awarded two six-year research fellowships.

Índice H: 14

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0464-3225

Scopus ID: https://acortar.link/fXn32g

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=Guzli5AAAAAJ&hl=es

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Beatriz-Catalina-Garcia

Academia.edu: https://urjc.academia.edu/BGarc%C3%ADa

María del Carmen García-Galera

Universidad Rey Juan Carlos.

Professor of Journalism (2023) at the Faculty of Communication Sciences, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos. Principal investigator of the high-performance research group Particypad (2015-). Professor of Audience Research (Journalism) and Strategic Planning of Public Relations (Advertising and Public Relations) Her main lines of research focus on informational disorders and employability of graduates in Communication. Three six-year research periods and more than 50 publications, both in scientific journals indexed in JCR and book chapters widely disseminated in the area of study. Academic Director of the Scientific Culture and Innovation Unit of the URJC (2021-), where she organizes, among others, the Science Week or the European Researchers' Night.

Índice H: 21

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6211-2700

Scopus ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=56245822500

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=QrUt7bcAAAAJ&hl=es

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/M-Garcia-Galera/

Academia.edu: https://independent.academia.edu/CarmenGarcíaGalera