Revista Latina de Comunicación Social.

ISSN 1138-5820

Fact-checking in electoral processes and permanent campaign. A comparative analysis between Spain and Portugal

Fact-checking en procesos electorales y campaña permanente. Un análisis comparado entre España y Portugal

Santana Lois Poch-Butler

Rey Juan Carlos University. Spain.

![]()

Roberto Gelado Marcos

CEU San Pablo University. Spain.

![]()

Borja Ventura-Salom

CEU San Pablo University. Spain.

![]()

Guillermo de la Calle Velasco

CEU San Pablo University. Spain.

![]()

Funding: This research is part of the IBERIFIER project, funded by the European Union through the CEF-TC-2020-2 agreement, under reference 2020-EU-IA-0252 and it has also received funding from the Research, Transfer and Scientific Dissemination Vice-Rectorate of the CEU San Pablo University.

![]()

ABSTRACT

Introduction: This research aims to study fact-checking from a double comparative perspective: on the one hand, geographical, comparing verification in Spain and Portugal; and, on the other, thematic, analyzing verification patterns —and, by extension, disinformation— in electoral and non-electoral periods. Methodology: To this end, the authors propose a study that triangulates between the statistical and discourse analysis of a study population composed of more than 2.500 fact-checkings (N=2.635) and five in-depth interviews with fact-checkers from all the fact-checking agencies integrated in the IBERIFIER hub, which is financed by the European Commission through EDMO. Results: Politics is the predominant thematic axis in the contents fact-checked in Spain (the electoral period also accentuates this trend); this is not so in Portugal. The most frequent type of fact-checked disinformation is false context and both social networks (mainly Facebook in Portugal, and Twitter/X and Facebook in Spain) and messaging platforms (WhatsApp) are the platforms from which fact-checkers most extract fact-checked content. Discussion: Similarities in discursive patterns are observed (imported narratives, recurrence of groups such as immigrants or the LGTBI community among the passive subjects of disinformation, among others). Conclusions: Electoral processes increase the vulnerability of the audiences to disinformation and can, in addition, monopolize the activity of fact-checking agencies to the point that they run out of sufficient resources to provide coverage to other areas on which they would work in a permanent campaign.

Keywords: fact-checking; disinformation; politics; elections; Spain; Portugal.

RESUMEN

Introducción: La presente investigación propone estudiar el fact-checking desde una doble perspectiva comparada: de un lado, geográfica, con España y Portugal como marcos de análisis; y, del otro, temática, analizando patrones verificadores —y, por extensión, desinformadores— en periodos electorales y fuera de ellos. Metodología: Se propone, a tal efecto, un estudio que triangula entre el análisis estadístico y de discurso de una población de estudio compuesta por más de 2.500 verificaciones (N=2.635), y las cinco entrevistas en profundidad a verificadores de todas las agencias de fact-checking integradas en el hub IBERIFIER, que financia la Comisión Europea a través del European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO). Resultados: La política es el eje temático predominante en los contenidos verificados en España (el periodo electoral acentúa, además, esta tendencia), no así en Portugal. La tipología de desinformación verificada más frecuente es el contexto falso y tanto redes sociales (principalmente Facebook en Portugal y Twitter/X y Facebook en España) como plataformas de mensajería (WhatsApp) son los canales de donde más extraen los fact-checkers los contenidos verificados. Discusión: Se observan similitudes en los patrones discursivos (narrativas importadas, recurrencia de grupos como los inmigrantes o el colectivo LGTBI entre los sujetos pasivos de la desinformación). Conclusiones: Los procesos electorales incrementan la vulnerabilidad de los públicos a la desinformación y pueden, además, copar la actividad de las agencias de fact-checking hasta el punto de que éstas se queden sin recursos suficientes para dar cobertura a otras áreas sobre las que sí trabajarían en campaña permanente.

Palabras clave: fact-checking; desinformación; política; elecciones; España; Portugal.

INTRODUCTION

Recent research (Hameleers & van de Meer, 2020) has addressed a worrying increase in the impact of disinformation and its collateral effects, such as institutional crisis or polarization of public opinion (Ekström et al., 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on the proliferation of informational disorders has also led to systematic research on the different typologies of disinformative content (Brennen et al., 2020). Against this backdrop, professional initiatives have also emerged to combat the impact of news disruption, a context that includes fact-checking. Academic research on fact-checking has approached the phenomenon from different perspectives, although, to a large extent, not a few studies have focused on its effectiveness. In this regard, authors such as Graves (2016) have spoken not only of the obvious relationship between verification and journalistic work but have also praised its role in preventing news disruptions; similarly to what authors such as Luengo and García-Marín (2020) have stated more recently.

Politics, social networks and other fact-checking challenges

In their research on the effects of fact-checking, Nyhan and Reifler (2015) referred precisely to one of these possible sources of disinformation, politicians, and concluded that the work of fact-checkers could dissuade them from disseminating proclamations that are too lightly supported by data. The link between disinformation (and, therefore, the efforts of fact-checkers to carry out an exercise of information transparency to counteract it) and politics has been pointed out both in academic and political spheres.

For years now, leading political institutions such as the European Commission (2018) have warned that the extent of disinformation is such that it may well be considered one of the most worrying threats to society in general, and to modern democracies in particular (Syrovátka et al., 2023; Bradshaw and Howard, 2018; Bennet and Livingstone, 2018). The political side of disinformation is also evidenced through two pivotal moments, the 2016 US presidential election and the brexit, which began with the referendum held that same year. These two key historical moments played out, in light of the academic literature, in several subsequent milestones: since the aforementioned US elections, disinformation has hovered over in various electoral processes around the world, from the Brazilian elections of 2018 (Santos, 2020) to the following US elections in 2020 (Benaissa, 2020) to the US elections in 2020 (Benaissa, 2020). Disinformation has been involved in various electoral processes around the world, from the Brazilian elections of 2018 (Santos, 2020) to the following US elections in 2020 (Benaissa, 2021), through the Cape Verdean presidential elections of 2016 (Novais, 2021), the independence referendum of 2017 (Alandete, 2019), the Spanish general elections of April 2019 (Magallón-Rosa, 2019) or the Portuguese parliamentary elections of the same year (Baptista & Gradim, 2022).

Fact-checking on misinformation, in general, and in the political sphere in particular, has frequently focused on social networks as an environment favorable to the dissemination of informational disruptions (Tandoc et al., 2018; Allcott et al., 2019). As explained by Pérez-Seoane et al. (2023),

it is not surprising, then, that in an era in which social networks channel a large part of public discourse and disinformation, fact-checkers have turned to these platforms as vehicles for distributing this content. (pp. 5-6)

Often, moreover, hoaxes are spread simultaneously through several social network platforms to increase the chances of impact. López-Martín et al. (2023) specifically point to Twitter/X (Larrondo-Ureta et al., 2021; Pierri et al., 2020; Morales-i-Gras, 2020) and Facebook (Baviera et al., 2022) as social networks where misinformation proliferates the most, followed by the messaging platform WhatsApp (Canavilhas et al., 2019).

In addition to the aforementioned academic concern about effectiveness, authors such as Dafonte-Gómez et al. (2022) have addressed other problems arising from the limited resources of fact-checking agencies, arguing that, in times when the news is dominated by a central theme (in the case of the research of these authors, the COVID-19 pandemic), hoaxes other than those mentioned above tend to be less fact-checked. Within these thematic axes tending to monopolize the fact-checking activity, Pérez-Seoane et al. (2023) highlight the reactivity of consumers of these fact-checked contents mainly when they deal with national political issues; and, secondarily, social or health issues; generally in formats in which graphics predominate (although other research, such as that of López-Martín et al. (2023) speak of a predominance of text in uninformative contents).

Patterns in the disinformative content orchestrated by different players are also relevant to analyze from a discursive point of view. Van Dijk (1995), by proposing an ideological discursive analysis, pointed out, in this regard, that "the meaning of discourse, as elaborated during production or comprehension, is likely to include opinions that derive from underlying logics" (p. 283). "Discourses," the author adds, "are not only coherent at the local level, but also at the total or global level, which can be specified in themes or issues and theoretically explained by semantic macrostructures" (Van Dijk, 1995, p. 282). In the specific case of "alt-right activists," Hodge and Hallgrimsdottir (2020) point out that these players "seek to create a new cultural frontier against globalization and integration, multiculturalism, and the blurring of distinctions between social categories in terms of race, gender, sexuality, and class" (p. 575), for which they "often exploit fear of the unknown to build a patriarchal base on anti-feminist, anti-LGTBI, racist, and anti-minority pretexts" (Fielitz & Thurston, 2019, p. 8).

Disinformation and fact-checking at the Iberian level

The geographical context of Spain and Portugal has not been, as might be expected, exempt from academic interest in disinformation and ways of mitigating its impact. In many of these cases, studies on disinformation have focused either on Spain (Macarrón et al., 2023; Ibáñez-Lissen et al., 2023; Almansa-Martínez et al., 2022; Salaverría et al., 2020; García-Marín & Salvat-Martinrey, 2021), or on Portugal (Silveira & Gancho, 2021; Sobral & Nina, 2020; Figueira & Santos, 2019; Lima et al., 2019) independently; although comparative studies have also been undertaken between both countries, focusing on the challenges posed by platforms such as TikTok (Alonso-López et al., 2021) or disinformative patterns in electoral times (Rivas-de-Roca et al., 2022).

The political sphere and electoral processes have also been one of the recurring themes in Iberian research on fact-checking as a spring against disinformation (Mazaira-Castro et al., 2019); although it has not been the only one: others, such as pandemics, have also copied these studies. Among the research focused on fact-checking activity in Spain, a good part has focused on the platforms, both of dissemination subsequently fact-checked (Bernal-Triviño & Clares-Gavilán, 2019), and of presentation of the fact-checking itself through channels such as Twitter/X (Argiñano-Herrarte et al., 2023), TikTok (García-Marín & Salvat-Martinrey, 2022) or WhatsApp (Palomo & Sedano, 2018); in addition to case studies on the work of fact-checking agencies such as Newtral (García-Marín et al., 2023; Pozo-Montes & León-Manovel, 2020) or Maldita (Herrero-Diz & Pérez-Escolar, 2022). Fact-checking activity has also been the subject of academic research in Portugal, such as that of Baptista et al. (2022), which focused on the production of fact-checkings by Polígrafo and Observador during the 2019 and 2022 legislative elections in the country.

Comparative efforts are also particularly interesting for the purpose of this research. These include Peña et al. (2021), which focused on Spain and Italy; Moreno-Gil et al. (2021), which compared practices in Spain and Latin America; and Magallón-Rosa and Sánchez-Duarte (2021), which analyzed the fact-checking activity of fact-checkers in four countries (Portugal, Spain, Italy and Greece) during seven months in 2020, in the context of the pandemic, which already warned of recurrent lines. The study confirms an increase in the activity of fact-checkers at times of greater information intensity and a higher presence of hoaxes in the Spanish environment compared to the other countries under study.

OBJECTIVES

This research poses a comparison of the fact-checking activity between Spain and Portugal as it is an aspect that has previously attracted academic interest and that the European Commission itself has found to be relevant by awarding the Iberian community a joint hub to fight disinformation within the framework of the European Digital Media Observatory's CEF-TC-2020-2 call for proposals. Likewise, given the profuse presence of disinformation (and, therefore, of fact-checking) in the political field, which has also been confirmed in the previous sections, it has been considered of particular interest to focus this comparative approach to the political field, in general, and to the comparison between electoral processes and the permanent campaign, in particular.

In this context, the following research objectives are proposed:

- To detect similarities and differences in the flow of fact-checked disinformation in Spain and Portugal.

- To examine which platforms and formats predominate in the dissemination of disinformation in the contents being fact-checked by Iberian fact-checkers.

- To determine what type of information disruptions predominate in the Iberian area in light of the contents being fact-checked by the fact-checkers.

- To provide context by analyzing whether there are identifiable deep narratives beyond individual hoaxes in both Spain and Portugal.

- To establish the extent to which fact-checking activity in Spain and Portugal focuses on activities directly or indirectly related to politics, both within and outside the electoral period.

METHODOLOGY

Since one of the objectives was to establish a comparison between electoral processes and permanent campaigning in Spain and Portugal, it was decided that the starting point of the research would be the beginning of the Portuguese campaign in 2022 (January 16), and its conclusion would be the date of the Spanish elections (July 23, 2023). The time frame also allowed for a large central block of permanent campaigning shared between January 30, 2022, and July 7, 2023 (the date indicated as the start of the campaign for the Spanish general elections.)

The members of the IBERIFIER hub (Maldita, EFE Verifica, Polígrafo, Verificat and Newtral) were chosen for the sample of fact-checking agencies, as this was the project designated by the European Commission through EDMO to fight disinformation in the Iberian region. All of them also have the IFCN seal, so their work is subject to the professional standards of this reference network. The possibility of extending the sample to other Portuguese fact-checking agencies was assessed (with the inclusion, for example, of fact-checkers such as Observador-FactCheck, also a signatory of the IFCN code.) However, it was finally ruled out in order to maintain, on the one hand, a sample that had institutional and academic support and, on the other hand, because the presence in IBERIFIER of all of them implied the submission to common criteria for the codification of their fact-checking -something that would be impossible to achieve with the introduction of additional fact-checkers.

IBERIFIER common fact-checking repository

Within the IBERIFIER project, one of the deliverables of activity A2 was the production of a repository of fact-checks that encompasses the contributions of the fact-checkers that were part of the group. Access to the complete database was provided through an API created within the framework of the project itself and fed by the fact-checkers following a series of agreed criteria. In the first instance, the API allows consulting the ID of each fact-check, its owner, date of creation and the organization to which the check belongs; at a second level, more detailed information can be accessed regarding the thematic category, sources, formats, and ratings or statements. The first level data mainly provided the approach to objective 3, referred to the narratives that could be perceived from the individual misinformation; as well as the aspects of objective 4 related to the frequencies and consequent comparisons in electoral periods and permanent campaign. The second level data, on the other hand, allowed to clarify objective 2 on the most common news disruptions, to shed more light on thematic aspects corresponding to objective 4 (the presence of politics in the fact-checked disinformation), and to address secondary objectives 1.1. and 1.2 on formats and platforms.

Regarding the variable of information disruptions detected by the fact-checking agencies, the categories agreed upon by the five IBERIFIER fact-checkers were followed: “Valid,” “Fake Alert,” “Fake Quote,” “Manipulated Content,” “Fake Context,” “Invent,” “Satire,” “Hoax/Fraud,” and “Others.” Similarly, for the variable “sentences” issued by the fact-checkers on the fact-checked content, seven common categories were agreed upon: “false,” “true,” “misleading,” “no evidence,” “explainer” and “unverifiable.”

The categories provided by the fact-checkers in the repository accessed for this research through the API designed for this purpose refer to the topics of each misinforming content, and the list was drawn up based on those used by the organizations that are part of the project. This variable divides the fact-checks into 20 excluding thematic categories: alerts, food, animals, science, consumption, environmental disasters, gender, migration, characters, politics, religion, health, security, sexuality, social, terrorism, scam, work, traffic and others. The “Sources” section shows the channels through which the disinformation covered by the fact-checks in the repository is disseminated. This variable is not exclusive (for each fact-check one or more of these dissemination channels can be selected) and the following categories are included: WhatsApp, Facebook, Twitter/X, Email, Instagram, TikTok, Telegram, Search Engine, Others. The non-exclusive variable “Formats” reveals information on how the disinformation about which the fact-checks deal with is being distributed and its categories are WhatsApp String, Video, Image, URL, Article, Tweet and Audio.

Research design

A total of 2,635 units of analysis were extracted from five fact-checkers and framed within a study period from January 16, 2022, to July 23, 2023. For their examination, the study triangulated between the quantitative approach of statistical analysis and the qualitative technique of discourse analysis. The first approach was intended to provide the research with the solidity that came from such an extensive and systematically compiled database; although it was understood that, in order to understand complex objectives such as the existence of disinformative narratives, it was necessary to complete everything that was impossible to quantify in order to explain a complex phenomenon such as fact-checking.

Similarly, the methodological design included a third research technique, the in-depth interview, aimed at comparing some of these results, as well as inquiring about aspects that partially or totally remained excluded from the analysis of descriptive statistics and the examination of the discourse (especially objective 5, focused mainly on the effects of misinformation and fact-checking). To this end, five in-depth interviews were conducted using a semi-structured questionnaire with scaled and open-ended questions. The interviews were conducted through Teams between November 27 and December 13, 2023, with five fact-checkers (one for each fact-checking agency belonging to IBERIFIER) with experience in political issues and appointed by the fact-checkers themselves. Table 1 shows both the data sheet and the questions asked in the semi-structured questionnaire.

Table 1. Semi-structured questionnaire for in-depth interview.

|

Name of the verifier/media: Name of the interviewee: Position: Name of the interviewer: Date: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Some of the variables addressed in certain questions of the questionnaire (especially those related to the thematic axes —question 4—, formats —question 5— and platforms related to the dissemination of disinformation —question 6—) had been arranged so that the analysis triangulates with other approaches (especially statistical) from which these same variables were investigated. Thus, if the same trends were confirmed from various research approaches, the validity of the results would be reinforced. Question 7 also expanded the research on the variable formats to an aspect on which no data were obtained in the statistical analysis: the effectiveness of fact-checking from the perspective of the fact-checkers according to the formats in which the fact-checked content was presented.

Finally, the first two questions of the questionnaire were directly related to the fourth research objective, which was also analyzed from the perspectives of discourse analysis and statistical analysis; while the third sought to complement the data obtained from discourse analysis with the perception of sources of authority in the field (the fact-checkers) regarding the existence of deep narratives that may connect, at times, a series of individual hoaxes. Table 2 provides a summary of the relationship between the objectives set out in the previous section and the techniques used to address each of them.

Table 2. List of research objectives and techniques in use.

|

Objective |

Technique being used |

|

O1 |

Statistical analysis, in-depth interviews |

|

O2 |

Statistical analysis |

|

O3 |

Discourse analysis, in-depth interviews |

|

O4 |

Statistical analysis, discourse analysis, in-depth interviews |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

RESULTS

Statistical analysis

The quantitative approach to several research objectives was carried out through a computer-assisted statistical study implemented by means of the SPSS Statistics 27 program. The data extracted from the API were used to analyze different aspects related to both the volume of production and the nature of the contents being fact-checked. Regarding the first section, the most productive fact-checking agency for the period under study was Maldita (1.140 items, 43,3% out of the total), followed by Polígrafo (18,6%), Newtral (16,6%), EFE Verifica (11%) and, lastly, Verificat (10,5%).

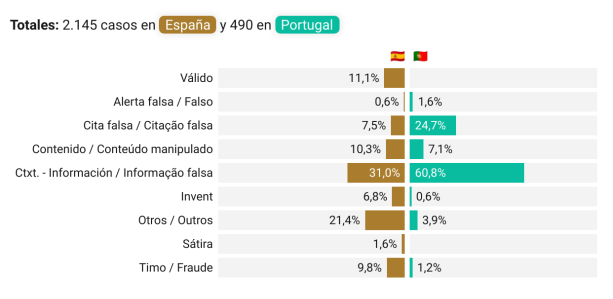

Types of fact-checked information

The most recurrent misinformation faced by these fact-checkers was fake context (36,5%), followed far behind by fake quotes (10,7%), manipulated content (9,7%), scam (8,2%) and fabrication (5,7%). Other typologies such as satire (1,3%) or fake alert (0,8%) have a minimal representation. The breakdown by country, as can be seen in Figure 1, does not show excessive differences in this ranking.

Figure 1. Types of fact-checked disinformation in Spain and Portugal.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Looking exclusively at election periods, the fake context once again stands out as the most frequent informative disorder, especially in Portugal, where it accounts for 93% of the fact-checked disinformation. In Spain, this also continues to be the most common form of misinformation during election periods (32,2%), followed by fake quotes with 19,2% of cases.

Predominant topics in fact-checked content

It is particularly interesting for the purposes of this research the special recurrence of political topics, present in almost a quarter of the sample (24,9%), in the fact-checked contents. Although none of the following categories reaches half of this percentage, they also have a significant presence: Science (11,8%), Social (8,8%), Characters (8,7%), Fraud (8,6%), Migration (6%) and Gender (4,3%). Figure 2 also shows significant differences in the comparison between countries: in Portugal, the leading role is shared among Consumption (11,6%), Social (10,6%), Health (8,8%) and Politics (8%), while in Spain the latter clearly predominates (28,8%), followed by Science (13,2%) and Fraud (10,5%).

Figure 2. Thematic axes of the fact-checked contents in Spain and Portugal.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

If focusing on the predominant topics within election periods, attention to political topics multiplies in Spain, where more than half of the fact-checked contents (52,1%) fall into this category. In Portugal, the data are too few (only 14 fact-checkings) to be significant, although they show a clear tendency towards Science (50%). In Spain, this same topic drops to 8,2% during the election period and falls to fourth place, surpassed by Migration/Racism (12,3%) and Characters (11,6%).

Formats and platforms

Regarding the most frequent formats in the dissemination of potentially disinformative content under study, images, both static (25,3%) and in motion (23,8%), represent half of the units analyzed. Articles (13,8%), tweets (12,6%) and Facebook posts (10,9%) are the other three categories recorded in the analyzed database that exceed the 10% threshold, ahead of URLs (4,9%), WhatsApp chains (4,1%), audio (0,3%), and Instagram stories (0,3%).

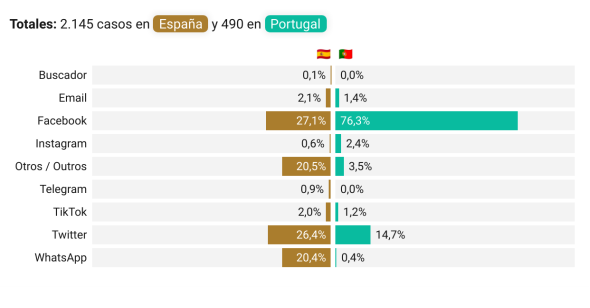

In terms of platforms, social networks and messaging platforms prevail in the transmission of disinformation, as evidenced by the fact that more than three quarters of the fact-checked content comes from such networks: Facebook works as a broadcaster in 36,2% of cases, Twitter/X in 24,3%, and WhatsApp in 16,7%, ahead of TikTok (1,9%), Instagram (0,9%), Telegram (0,7%) and search engine (0,1%).

There are also differences between the dominant platforms when comparing countries, as shown in Figure 3. While in Spain the leading role is shared between Facebook (27,1%) and Twitter/X (26,4%), and WhatsApp (20,4%) having a significant presence, in Portugal, Facebook (76,3%) is more than five times the second most recurrent channel - also Twitter/X (14,7%).

Figure 3. Channels for transmitting disinformation content in Spain and Portugal

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Frequency of publication of fact-checked content

Finally, the quantitative analysis shows differences in the publication patterns of fact-checkings in Spain and Portugal. The frequency maps in Figure 4 show a much more constant profile in Portugal, whose volume is less affected by the January 2022 electoral process than its Spanish counterpart in the July 2023 general elections. Fact-checking activity in Spain increases significantly from March 2023 onwards –reaching levels that had only been seen in the same month of the previous year– and rises even more between May and July (probably as a result of an extended election campaign beyond the official period).

Figure 4. Frequency of publication of fact-checked content in Spain and Portugal.

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Analysis of the disinformative discourse

The narrative shows the presence of three differentiated groups of disinformation. The first refers to disinformation in general. Fact-checkers deal with it in a reactive way - they detect the content and make a response. The second is aimed at verifying the authenticity of statements by politicians, which the agencies proactively select -they decide which ones to select-. Both are relevant in this research for the Spanish case, since they address political communication issues. The third group, less relevant in this case, refers to public service disclaimers, which aim to reply to citizens' questions -therefore, reactive-, clarify doubts or add context -proactive- or warn about scams and swindles.

The discourse analysis focuses, therefore, on the first two groups because they are the ones that refer to the object of this research. This allows, as a starting point, to note that most of the disinformation is critical in relation to left-wing ideas, representatives or political groups. In the case of the fact-checkings of Spanish agencies, there are critical cases regarding classic right-wing representatives or groups, but most of them favor the radical right -not the left-:

The PP in Andalusia forces schools to celebrate Gay Pride day, only Vox opposes it... you vote PP, don't hesitate, go on… (EFE Verifica.)[1]

Madrid citizens spend 57% of their salary to pay the rent, which does not stop rising [...] But the aids are always taken by the same people (Maldita.)[2]

Maria Guardiola, the PP candidate in Extremadura refuses to make a pact with VOX and offers the government to the socialist Vara (Maldita.)[3]

The narrative of the disinformation recurrently favors ideological frameworks defended by Vox, in Spain, and Chega! in Portugal. In this regard, the scarce presence of disinformation favoring left-wing ideological frameworks is striking, which may be due to their lower incidence or to possible biases in the selection process of the fact-checkers. With regard to the group of general thematic disinformation, there are large recurring themes. Most of them, although they do not refer to political issues, they consistently correspond to ideological postulates of the aforementioned radical right.

In the analyzed sample there are issues such as racism, anti-minority discourse -with emphasis on anti-feminist, anti-LGTBI and especially anti-trans rhetoric-, unscientific statements in general, health conspiracy -especially with the pandemic- or climate skepticism and criticism of environmental policies, among other topics.

Parallel to these issues, there are others that are political, such as speeches in line with Russian propaganda. Thus, the invasion of Ukraine is used as a narrative canvas to slip ideas about the legal non-existence of the country, to justify the war by NATO expansionism, to accuse Ukrainian leaders of Nazi ties and refugees of criminal acts, to question Russian attacks or to ridicule the political representatives of Ukraine and the USA:

Ukraine does not exist as a country. In the UN it continues as a Russian territory, so there is no invasion (Polígrafo.)[4]

Why did these Russians put their country in the middle of the NATO bases!? ?? 😒 (Polígrafo).[5]

Artem Bonov, deputy police chief of the Kiev region, has tattoos with Nazi symbols (Maldita).[6]

The owners, fed up with the behavior of Ukrainian 'refugees', have put up signs saying they are not welcome in those premises (EFE Verifica).[7]

Joe Biden touches Zelenski's ass during his trip to the U.S. (Maldita).[8]

Video of a corpse in Bucha (Ukraine) raising its hand (Maldita).[9]

Ukrainian President Volodymir Zelenski says in this interview that he uses cocaine (Maldita).[10]

Although this research focuses on political discourse, it is clear that all the thematic 'nodes' mentioned above meet certain characteristics that make it difficult to separate them: (1) none of them act in isolation, as they intertwine to reinforce each other's arguments; (2) all of them fit the geographical context —i.e., they use elements adapted to Spain or Portugal—; (3) all of them fit the news context of the moment —i.e., they use real events to intensify narratives as appropriate—.

This link between ideas also occurs through the association of conceptual frameworks with political entities. In the case of Spain, where most of the critical readings concern the parties of the governing coalition —PSOE and Podemos—, it can be observed in a very strong way with regard to discourses against minorities —especially in equality policies, sex education or the 'trans' community—, or with skepticism about climate change and environmental policies. In the case of Portugal, for example, it is linked to immigration, connecting it with the left, globalism and, directly, the government:

The government spends €20,000 million on feminist talks. At the same time, 4.5M Spaniards cannot pay their electricity bill (Maldita).[11]

This image appears in a textbook for 4-year-old children in Castellón. The trans law, already approved, protects it. Abhorrent! (Maldita).[12]

The team of a guy, who thanks to the new Trans Law can feel like a woman and play in the women's league, ends up winning by 23 goals to 0 (Maldita).[13]

The Ministry of Ecological Transition spends more than 10,000 euros on a campaign to get Spaniards to use fewer washing machines and wash clothes by hand (Maldita).[14]

Fifty-four percent of Lisbon is not Portuguese [...] or PS, which claims to serve the people who elected it but humiliates our own people (Polígrafo).[15]

Generally speaking, and no longer linearly political, other links can be noticed. For example, Russian propaganda is combined with anti-globalist themes when NATO is attacked, or health conspiracy theories are combined with anti-globalism when criticizing the WHO, with racism when it is claimed that those who have been vaccinated will be favored, or with libertarianism when disinformation is produced about the supposedly harmful effects of vaccines imposed by countries:

Merkel reveals how the US and NATO planned the Ukraine war. The former German Chancellor is the latest Western source to come clean (Maldita).[16]

What does the single party of the Portuguese Republic Assembly say about the delivery of sanitary sovereignty to the World Health Organization? (Polígrafo).[17]

Compulsory Digital Identity in Ukraine, with Compulsory Vaccination, to get “war compensation”! (Maldita).[18]

At COVID hearing, Pfizer director admits: vaccine was never tested to prevent transmission (EFE Verifica).[19]

In terms of a contextual and/or timing adaptation, disinformation uses references to foreign countries - more difficult for the average citizen to know and, therefore, to refute - to promote critical visions of local politics. This adaptation can be seen in the fact that, in Portugal, the criticisms refer to Brazil - a Portuguese-speaking country. This trend intensifies with the elections in which Jair Bolsonaro was defeated by Luiz Inázio Lula da Silva, a moment in which they turn the narrative to an alleged electoral manipulation, in addition to the background approach in which the left-wing candidate is associated with corruption:

Lula won the vote in Barreiras, Bahia, with 213,243 votes. 156.975 (2020) inhabitant of Barreiras, Bahia (Polígrafo).[20]

The waiter made a copy of Lularapio's and his companions' lunch account. A small bagatelle of 9,400 euros (Polígrafo).[21]

I lived long enough to see a newly elected president personally thank the support of the drug trafficker's boss, directly in prison (Polígrafo).[22]

In Spain, this use of foreign politics to make internal criticism is less notorious, but it does happen. In fact, it is also adapted -in this case to a Spanish-speaking country- and corresponds to the news context -the presidential elections in Colombia, also won by the leftist candidate- spreading the same idea that is then internally generated -the electoral manipulation-:

Petro has the registrar and the 'software' [...] made by the company INDRA, owned by the Spanish socialist government, to steal the elections (EFE Verifica).[23]

Montero, being categorical: “They will never find me with a cocaine trafficker” [...] Petro, recently elected president of Colombia, next to Pablo Escobar (Maldita).[24]

It is especially relevant the amount of denials throughout the series and in both countries, referring to the riots in France and how they are associated to many of the issues above mentioned, especially racism. It is relevant, in addition to its incidence -elaborating a portrait of a failed multicultural society-, because of the symbolism of the country as the founder of the EU -the common framework of Spain and Portugal-, which is, in addition, a political battleground where the alternative right has disputed the second round in three of the last five presidential elections (2002, 2017 and 2022).

The international component is also used in the other way around, in the specific case of Portugal. Thus, throughout the period under analysis, there is a constant stream of disinformation aimed at questioning the country's image abroad:

This in Portugal, from the Costa government, where golden subsidies and immoral pensions are practiced, over 10,000 euros, up to 167,000 euros (Polígrafo) [25]

This is a crime index for European cities and unfortunately Amadora is already in 18th place (Polígrafo)[26].

The Portuguese state has an average payment period of 75 days. European Union states take an average of 42 days (Polígrafo)[27].

This is a tendency that can be observed both during and after the presidential campaign, spreading messages about certain ideas, possibly seeking their acceptance, depending on the recipient's predisposition, and dissemination, under certain circumstances. This report is also established through links with another series of disinformation aimed at trying to create a feeling of poor management of public resources - in terms of health, property or infrastructure, for example - by the government:

Despite being the country with the most doctors and nurses per inhabitant in Europe, the ratio of the population with health limitations [...] is [...] 25,2% (Polígrafo)[28].

At the end of 2010, public debt reached 149.4 billion euros. In March 2023, the public debt already stood at 279.3 billion euros (Polígrafo)[29].

Has anyone ever asked the former minister to account for the millions spent on buying the famous Spanish carriages from Renfe, which are now abandoned? (Polígrafo)[30].

With regard to the Spanish case, there is a line of denials to more ideological disinformation. Although, as in Portugal, the framework is set through themes that are not necessarily political -social issues, for example-, in Spain disinformation is more often accompanied by direct references to certain ideas, leaders or entities, almost always left-wing. It happens, for example, with racism, which is sometimes presented together with the idea of criminality and it is linked to current events in order to create 'coherent' frames within the general narrative while reaffirming the message.

Thus, manipulated exaggerations of feminism are used as a criticism of Podemos, or the idea that the Government favors immigrants over other groups -'us' vs. 'the others'- is fostered for months in order to, during the campaign, suggest that they will then vote for the left to perpetuate these supposed advantages while claiming identity values -opposing them to symbolic groups, such as the State Security Forces and Organizations-. First, they disseminate ideas that the left gives favorable treatment to immigrants:

Average monthly salary of a policeman and civil guard is 1.500.-€ and some Africans IN ILLEGAL SITUATION are receiving from the state 2.000.-€/month? (Maldita) [31]

#URGENT Pedro Sánchez🇪🇸 gives to Nigeria🇳🇬 1,700 million € for the development of the African country (Maldita)[32].

Soon the municipal swimming pool will be open[...], what a good thing, buuuUUUUUt,,,,, supposedly it is said that two days a week only Muslims will be able to enter (Maldita)[33].

The socialist mayor of León [...] has promised that if they vote for him he will build their own slaughterhouse, a madrassa [...] and a Muslim cemetery (Newtral)[34].

Afterwards, usually already in the campaign, the narrative is modified to imply that the left-wing parties aim to collect the fruits in the form of electoral mobilization of the supposedly favored, in a self-conclusive justification of their disinformative narrative:

More than 6,300 corrupt votes for the PS [...] More than 6,300 citizens of the CPLP asked for residency authorization online in just 2 hours (Polígrafo)[35].

Morocco disseminates a letter asking its citizens residing in Spain to vote for the PSOE in the elections of May 28, 2023 (Newtral)[36].

The Government, by means of a royal decree, has approved a massive regulation of 470,000 illegals to whom it will give nationality to vote for the PSOE (Newtral)[37].

That approach has a very prominent variant in the Spanish campaign directly pointing to an alleged electoral fraud. In this case, the idea is not only linked to racism, but acts through events invented or taken out of context and sometimes used by the opposition itself:

The electoral rolls are arriving to the houses in Huelva and they have gone to claim to the padrón and they do not stay in the padrón but they do come to the electoral roll (Maldita)[38]

Postal fraud in the Community of Madrid [...] 67.000 postal votes have disappeared and the difference between votes requested and cast is suspicious (Newtral)[39].

Recorded in a post office in Leon, where a TON of ballots were being inserted for the General Elections of J 23 (Maldita)[40].

They are putting in the mailboxes of the houses fake ballots for the elections. Specifically they have falsified those of the PP and those of VOX (Maldita)[41].

The CERA vote in Madrid for J23 exceeds in CERA voters [...] an increase of almost 700% [...] Similar ratios are seen in Barcelona and Valencia (Maldita)[42].

All these thematic and argumentative trends are evident, with the peculiarities of context, both in Spain and in Portugal and, recurrently, both during the campaigns of each country -January 2022, July 2023- and in between.

Portuguese disinformation during the campaign is more focused on socioeconomic and health criticism. The Spanish ones, on the other hand, are more specific after the autonomic and municipal elections of May 2023 -disinformation about an alleged electoral fraud-, in addition to the aforementioned shift in the narrative about the government and immigrants.

In-depth interviews with fact-checkers in Spain and Portugal

There is a clear agreement among the fact-checkers interviewed, both in Spain and in Portugal, regarding the increase in fact-checking activity around electoral processes: all of them answer affirmatively when asked about it. Many of them also introduce interesting nuances to this question. From Newtral, for example, it is confirmed that in electoral times “we do produce more”; although this increased activity is not necessarily accompanied by an increase in resources: “during the year, the fact-checkings are on different topics; [...] (but) when there are elections, we put all the team's resources into checking (electoral) hoaxes [...] (and) into political fact-checking”. Polígrafo agrees that “the activity is much higher because the dissemination of disinformation becomes greater”.

When asked about the possibility that disinformation can distort -or has already distorted- some electoral result, the consensus seems to be repeated, with the exception of Verificat, which declines to use the word “distort” and opts for “affect”: “There are people who can decide their vote on the basis of disinformative content, and that is the most dangerous [...] (although) I do not know if that person has simply been re-assured by that disinformation content or has changed his or her vote. On this you would have to do an academic research; I, as a fact-checker, do not have data to answer you in any sense.” Newtral also speaks in terms of influence rather than distortion; and from Maldita they add that “the degree of polarization we have is also influenced by the amount of disinformation that circulates. I believe that this has an influence when it comes to voting, but then there is also the second round of electoral disinformation, which [...] is to prepare the narratives if the vote you wanted does not come out.”

It is interesting to confirm that, when the fact-checkers who were interviewed give examples of influence to explain the answer, they always refer to countries other than their own. Polígrafo, for example, first answers the question about the hypothetical distortion in a very direct way: “yes, we have already seen it,” and then qualifies: “I have no proof of cause-effect, but we saw (what happened with) Cambridge Analytica and even during the Brexit [...] if it was enough to change the result, we will never know; but it had an effect, the results were seen and we know what those who disseminated that fake news wanted.”

Similarly, EFE Verifica also mentions the U.S. presidential elections in 2016 or the Brexit and it is even more explicit when comparing ab intra and ad extra: “I believe that it has contributed (to the distortion) in other countries. I have more doubts (about whether disinformation has distorted electoral results) in Spain, because I think that what has been spread in Spain [...] and this is a personal opinion, I have no data to support this argument, (is that) more people have become angry, people who had already had their vote somehow decided”.

Formats and platforms

Regarding the format in which fact-checked disinformation appears most frequently during election periods, text is usually the most frequent response, although there is no clear consensus. Maldita equates the impact of text to that of image, although it places the latter above the former, while Newtral maintains that video format is more frequent. For its part, EFE Verifica considers that visual formats predominate (first static image, then video), while for Verificat and Polígrafo it is text that is more common. The only point on which almost all the fact-checkers studied seem to agree is that, so far, audio is the least common format. Newtral, however, warns that, although audio cases are not the most frequent, “in (electoral) campaigns they can be dangerous; as happened, for example, in the Andalusian elections”. Newtral, in fact, raises the audio format to third place at election time, from fourth place in the permanent campaign.

As for the channel through which the disinformation that interviewees verify usually spreads, the consensus is overwhelming: they all name, in this order, social networks and messaging platforms as the main environments in which disinformation is transmitted, both during and outside electoral times. Among the social networks, there is a certain consensus in identifying Twitter/X as an environment in which disinformative content proliferates, although Polígrafo points first to Facebook, in a specificity that can perhaps be explained by the country context. Maldita, for its part, warns of the possible emerging danger of TikTok —a social network also highlighted by EFE Verifica—, “where young people who enter the social network to have a good time find disinformative content whose formats match the language used in TikTok”.

In the debate on formats and platforms, it is also interesting what the interviewees consider should be done when presenting the fact-checking. “The essence of the denial article”, they say from Maldita, ‘should be a classic, medium-long web page article (format), because you have to explain your sources and how you have reached the qualification of hoax;’ although this clashes with a worrying reality: “People do not read. That is, they don't get involved (in the development of the fact-checking). So, from the beginning we do have a very long headline design; but (it is because) we are aware that many people are not going to click on that link.” EFE Verifica confirms this perception: “very often people [...] are posting things that show that they have not read the article. They are reacting only on what would be the equivalent of a headline”. This is why all interviewees refer to the need to publish fact-checkings on other platforms to approach those audiences precisely where disinformation is being consumed, to counteract it. Polígrafo mentions Facebook; Verificat, Twitter/X (their usual fact-checking work environment), Instagram and TikTok; and Maldita, Instagram and TikTok, the latter platform where, they point out, “we have to strategically be, and we are working to achieve more impact”.

Several interviewees also point out the link with current affairs as an influential factor in the possibility that the fact-checked contents are attractive to the audience. From EFE Verifica they specifically point out that what calls the attention is “always what has to do with current affairs, that is to say, what worries people”.

Narrative patterns: life cycle of disinformation and recurring thematic axes

The success of fact-checking in such ephemeral moments of high production of verifiable content as the electoral debates depends, largely, on the previous work. “In each election,” Verificat comments, 'if you consider doing pre-bunking, you have to be aware of what the main narratives are going to be.' This is something that, they point out, they prepared very well for the municipal elections in Barcelona in May 2023, but did not work so well for the general elections in July of the same year. “With a view to the general elections, since we didn't see it coming.... That (the time to prepare for the municipal elections of 2023) was a work of 4 or 5 months; because we obviously could not dedicate ourselves only to this [...] For the general elections there was no time, because many of the information (that we published for the municipal elections) we had obtained it through a request for transparency; and that takes time. Then, in addition, the deadlines can be met, and you can receive it... or not; and if you don't receive it, you have to resort to it.”

Regarding the thematic axes of disinformation, the fact checkers do raise important nuances within and outside the electoral processes; although politics is a common denominator quite explicit in all the responses in this regard during the permanent campaign: four Spanish interviewees mention politics as the first of these recurring themes and the fifth specifically mentions electoral processes. The only one who does not explicitly mention politics is Polígrafo, which mentions immigration first.

During election periods, several of the fact-checkers agree in pointing out a predominance of imported narratives -already advanced in discourse analysis- and the importance of anchoring with reality. In Maldita they point out, for example, that “there are certain techniques and narratives that are imported from the United States [...] Disinformers can use anything that is out of the ordinary to say: ‘this is an anomaly, and this anomaly means that there is electoral fraud.’ [...] So there they had: the contact with reality. It is true that the vote by mail has increased a lot, so they can generate the fantasy, the disinformation: 'this is because they are manipulating the vote by mail.'” Thus, they conclude, “between the fact that it was imported from the United States [...] and that they were able to start generating the narrative that there were strange things in these elections with these two data (call in summer and change in the legislation of the CERA vote), the issue of electoral fraud has shot up a lot, at least in these elections.”

EFE Verifica confirms this tendency, also pointed out in the discourse analysis, to “question the democratic guarantee, the legitimization of the process.” The same applies to Verificat, which mentions (as well as other fact checkers who were interviewed) the recurrent hoax of Indra and the recount of votes. Newtral also mentions this tendency when referring to hoaxes created from the “strong idea” of vote-buying. It is also interesting that this questioning of the legitimacy of the system does not appear in Polígrafo's response, which does mention, instead, the logic of the narratives imported also to Portugal.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

This study of the activity of fact-checkers in Spain and Portugal inside and outside electoral periods not only follows the comparative approach undertaken by previous research (Magallón-Rosa & Sánchez-Duarte, 2021) but also confirms through various research approaches some trends on which we propose to reflect in this section of conclusions.

On the one hand, there is a clear contrast between the predominance of politics as a thematic axis in the contents that were fact-checked in Spain and the lower relevance of this topic in the fact-checking in Portugal, as confirmed by the statistical analysis, the in-depth interviews and the discourse analysis. This higher incidence of political disinformation in the Spanish environment - emphasized, moreover, at election time - may be symptomatic of greater politicization and polarization in Spain. The in-depth interviews have also drawn attention to threats derived from the limited resources of fact-checking, in line with what Dafonte-Gómez et al. (2022) pointed out; such as the fact that an excessive focus on political issues during periods of high fact-checking activity such as electoral processes diminishes the capacity to fight disinformation elsewhere.

Similarly, although there is no absolute coincidence on the most recurrent format of presentation of disinformative content, the data collected from the statistical analysis and in-depth interviews -which also included this item, given that the categories collected in the API were sometimes not entirely enlightening-, there is a certain predominance of visuals, both static (images) and in motion (video).

Likewise, there are coinciding patterns in the narratives that appear in Spain and Portugal, such as the fact that not a few of them are imported or that, especially around electoral processes, they focus on recurring groups such as immigrants or the LGTBI community.

In both Spain and Portugal, social networks and messaging platforms are the channels most likely to spread disinformation. Differences are observed, however, within these large groups: while in Portugal Facebook is the channel that monopolizes fact-checked content, in Spain the leading role is shared between Facebook, Twitter/X and WhatsApp, which renews the timeliness of what has been concluded in several previous studies (Canavilhas et al., 2019; Larrondo-Ureta et al., 2021; Pierri et al., 2020; Morales-i-Gras, 2020; Baviera et al., 2022; López-Martín et al., 2023). It is also interesting, in this regard, that several Spanish fact-checkers point out the growing risk of platforms such as TikTok and Telegram, despite their low impact on the content under analysis. The effectiveness of the interest expressed by fact-checkers in combating disinformation being more present on these other platforms may also be the subject of future research.

Regarding the danger posed by disinformation, it is striking that fact-checkers, in general, accept the vulnerability of the target audience to disinformation by positioning them closer to not being able to discern hoaxes and reality than the opposite, and by unanimously agreeing that this is accentuated at election time. If we relate this vulnerability to the tendency also detected not to read contents that have been developed for fact-checking, the fight against information disruption is revealed as a challenge of increasing difficulty.

About the predominant type of disinformation, the fact that the statistical analysis shows the prevalence -both in Spain and Portugal and in electoral periods and permanent campaign- of the fake context information disorder is consistent with the indispensable anchoring with the reality mentioned in the in-depth interviews as a mechanism to increase the impact of disinformation: the danger seems to increase when the disinformation is not a complete invention.

In addition to some possible lines of research already pointed out and the limitation of the imbalance between Portuguese and Spanish fact-checkers - justified because the sample used favored a consensual categorization and, therefore, a systematic and consistent count -, it is worth suggesting that future research, maintaining a sample of fact-checkers who share the methodology of data collection, explore ways to expand their number and representativeness to several countries (perhaps expanding experiences such as Comprobado).

Finally, it is worth taking up the proposal of one of the fact-checkers to analyze in depth something that our research has only pointed out as a result of the agreement of several fact-checkers: to determine whether disinformation, at election time, has a reinforcing effect on the confirmation bias itself or whether it can modify voting intentions.

REFERENCES

Alandete, D. (2019). Fake news: La nueva arma de destrucción masiva. Deusto.

Allcott, H., Gentzkow, M., & Yu, C. (2019). Trends in the diffusion of misinformation on social media. Research & Politics, 6(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168019848554

Almansa-Martínez, A., Fernández-Torres, M. J., & Rodríguez-Fernández, L. (2022). Desinformación en España Un año después de la COVID-19. Análisis de las verificaciones de Newtral y Maldita. Revista Latina De Comunicación Social, 80, 183-200. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2022-1538

Alonso-López, N. Sidorenko-Bautista, P., & Giacomelli, F. (2021). Beyond challenges and viral dance moves: TikTok as a vehicle for disinformation and fact-checking in Spain, Portugal, Brazil, and the USA. Anàlisi: Quaderns de Comunicació i Cultura, 64, 65-84. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/analisi.3411

Argiñano-Herrarte, J. L., Goikoetxea-Bilbao, U., & Rodríguez-González, M. M. (2023). La verificación centrada en Twitter: análisis del fact-checking de los nutricionistas españoles en redes sociales. Zer, 28(54), 121-140. https://doi.org/10.1387/zer.24666

Baptista, J. P., & Gradim, A. (2022). Online disinformation on Facebook: the spread of fake news during the Portuguese 2019 election. Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 30(2), 297-312. https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2020.1843415

Baptista, J. P., Jerónimo, P., Piñeiro-Naval, V., & Gradim, A. (2022). Elections and factchecking in Portugal: the case of the 2019 and 2022 legislative elections. Profesional de la información, 31(6), e310611. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2022.nov.11

Baviera, T., Sánchez-Junqueras, J., & Rosso, P. (2022). Political advertising on social media: Issues sponsored on Facebook ads during the 2019 General Elections in Spain. Communication & Society, 35(3), 33-49. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.35.3.33-49

Benaissa Pedriza, S. (2021). Sources, Channels and Strategies of Disinformation in the 2020 US Election: Social Networks, Traditional Media and Political Candidates. Journalism and Media, 2, 605-624. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia2040036

Bennet, W., & Livingston, S. (2018). The disinformation order: Disruptive communicative and the decline of democratic institutions. European Journal of Communication, 33(2), 122-139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323118760317

Bernal-Triviño, A., & Clares-Gavilán, J. (2019). Uso del móvil y las redes sociales como canales de verificación de fake news. El caso de Maldita.es. Profesional de la información, 28(3), e280312. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2019.may.12

Bradshaw, S., & Howard, P. N. (2018). The Global Organization of Social Media Disinformation Campaigns. Journal of International Affairs, 71(1.5), 23-32. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26508115

Brennen, J. S., Simon, F. M., Howard, P. N., & Nielsen, R.-K. (2020). Types, sources, and claims of Covid-19 misinformation. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Factsheet, 1-13. https://bit.ly/4d8Cxqm

Canavilhas, J., Colussi, J., & Moura, Z. B. (2019). Desinformación en las elecciones presidenciales 2018 en Brasil: un análisis de los grupos familiares en WhatsApp. Profesional de la información, 28(5), e280503. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2019.sep.03

Comisión Europea (2018). Communication - Tackling online disinformation: a European approach. https://n9.cl/qwnzo6

van Dijk, T. A. (1995). Discourse semantics and ideology. Discourse & Society, 6(2), 243-289. https://bit.ly/47RIF2l

Dafonte-Gómez, A., Míguez-González, M. I., & Martínez-Rolán, X. (2022). Los fact-checkers iberoamericanos frente a la COVID-19. Análisis de actividad en Facebook. Observatorio (OBS*), 16(1), 160-182. https://doi.org/10.15847/obsOBS16120221823

Ekström, M., Lewis, S. C., & Westlund, O. (2020). Epistemologies of digital journalism and the study of misinformation. New Media and Society, 22(2), 205-212.

Fielitz, M., & Thurston, N. (Eds.). (2019). Post-digital cultures of the far right: online actions and offline consequences in Europe and the US. transcript Verlag. https://bit.ly/48RTrHb

Figueira, J., & Santos, S. (2019). Percepción de las noticias falsas en universitarios de Portugal: análisis de su consumo y actitudes. Profesional de la información, 28(3), e280315. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2019.may.15

García-Marín, D., & Salvat-Martinrey, G. (2021). Investigación sobre desinformación en España: Análisis de tendencias temáticas a partir de una revisión sistematizada de la literatura. Fonseca, Journal of Communication, 23, 199-225. https://doi.org/10.14201/fjc202123199225

García-Marín, D., & Salvat-Martinrey, G. (2022). Viralizar la verdad. Factores predictivos del engagement en el contenido verificado en TikTok. Profesional de la información, 31(2), e310210. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2022.mar.10

García-Marín, D., Rubio-Jordán, A. V., & Salvat-Martinrey, G. (2023). Chequeando al fact-checker. Prácticas de verificación política y sesgos partidistas en Newtral (España). Revista De Comunicación, 22(2), 207-223. https://doi.org/10.26441/RC22.2-2023-3184

Graves, L. (2016). Boundaries Not Drawn. Journalism Studies, 19(5), 613-631. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670x.2016.1196602

Hameleers, M., & van der Meer, T. G. L. A. (2020). Misinformation and Polarization in a High-Choice Media Environment: How Effective Are Political Fact-checkers? Communication Research, 47(2), 227-250. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650218819671

Herrero-Diz, P., & Pérez-Escolar, M. (2022). Análisis de los bulos sobre covid-19 desmentidos por Maldita y Colombiacheck: efectos de la infodemia sobre el comportamiento de la sociedad. Palabra Clave, 25(1), e2517. https://doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2022.25.1.7

Hodge, E., & Hallgrimsdottir, H. (2020). Networks of Hate: The Alt-right, “Troll Culture”, and the Cultural Geography of Social Movement Spaces Online. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 35(4), 563-580. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2019.1571935

Ibáñez-Lissen, L., González-Manzano, L., de Fuentes, J. M., & Goyanes, M. (2023). On the Feasibility of Predicting Volumes of Fake News—The Spanish Case. IEEE Transactions on Computational Social Systems, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSS.2023.3297093

Larrondo-Ureta, A., Fernández, S. P., & Morales-i-Gras, J. (2021). Desinformación, vacunas y COVID-19. análisis de la infodemia y la conversación digital en Twitter. Revista Latina De Comunicación Social, 79, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2021-1504

Lima Quintanilha, T., Torres da Silva, M., & Lapa, T. (2019). Fake news and its impact on trust in the news. Using the Portuguese case to establish lines of differentiation. Communication & Society, 32(3), 17-33. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.32.27872

López-Martín, Á., Gómez-Calderón, B., & Córdoba-Cabús, A. (2023). Disinformation, on the rise: An analysis of the fake news on Spanish politics. VISUAL REVIEW. International Visual Culture Review, 14(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.37467/revvisual.v10.4596

Luengo, M., & García-Marín, D. (2020). The performance of truth: politicians, fact-checking journalism, and the struggle to tackle Covid-19 misinformation. American Journal of Cultural Sociology, 8(3) 405-427. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41290-020-00115-w

Macarrón Máñez, M.T., Moreno Cano, A., & Díez, F. (2023). Impact of fake news on social networks during COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Young Consumers, 25(4), 439-461. https://acortar.link/9P2cPj

Magallón Rosa, R. (2019). Desinformación en campaña electoral. Telos: Cuadernos de comunicación e innovación. https://bit.ly/3Ac9RLW

Magallón-Rosa, R., & Sánchez-Duarte, J. M. (2021). Information verification during COVID-19. Comparative analysis in Southern European Countries. Thematic dossier International Relations and Social Networks. https://doi.org/10.26619/1647-7251.DT21.10

Mazaira-Castro, A., Rúas-Araújo, J., & Puentes-Rivera, I. (2019). Fact-checking in the televised debates of the Spanish general elections of 2015 and 2016. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 74, 748-766. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2019-1355en

Morales-i-Gras, J. (2020). Cognitive Biases in Link Sharing Behavior and How to Get Rid of Them: Evidence from the 2019 Spanish General Election Twitter Conversation. Social Media + Society, 6(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120928458

Moreno-Gil, V., Ramon, X., & Rodríguez-Martínez, R. (2021). Fact-checking Interventions as Counteroffensives to Disinformation Growth: Standards, Values, and Practices in Latin America and Spain. Media and Communication, 9(1), 251-263. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v9i1.3443

Novais, R. A. (2021). Veracity Pledge or Discreditation Strategy? Accusations of Legacy Disinformation in Presidential Campaigns in Cabo Verde. Southern Communication Journal, 86(3), 201-214, https://doi.org/10.1080/1041794X.2021.1903539

Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2015). The effect of fact-checking on elites: A field experiment on U.S. state legislators. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 628-640. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12162

Palomo, B., & Sedano, J. (2018). WhatsApp como herramienta de verificación de fake news. El caso de B de Bulo. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 73, 1384-1397. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2018-1312

Peña Ascacíbar, G., Bermejo Malumbres, E., & Zanni, S. (2021). Fact checking durante la COVID-19: análisis comparativo de la verificación de contenidos falsos en España e Italia. Revista De Comunicación, 20(1), 197-215. https://doi.org/10.26441/RC20.1-2021-A11

Pérez-Seoane, J., Corbacho-Valencia, J. M., & Dafonte-Gómez, A. (2023). An analysis of the most viral posts from Ibero-American fact-checkers on Facebook in 2021. ICONO 14. Scientific Journal of Communication and Emerging Technologies, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.7195/ri14.v21i1.1951

Pierri, F., Artoni, A., & Ceri, S. (2020). Investigating Italian disinformation spreading on Twitter in the context of 2019 European elections. PLoS ONE, 15(1), e0227821. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227821

Pozo-Montes, Y., & León-Manovel, M. (2020). Plataformas fact-checking: las fakes news desmentidas por Newtral en la crisis del coronavirus en España. Revista Española de Comunicación en Salud, 103-116. https://doi.org/10.20318/recs.2020.5446

Rivas-de Roca, R., Morais, R., & Jerónimo, P. (2022). Comunicación y desinformación en elecciones: tendencias de investigación en España y Portugal. Universitas- XXI, 36, 71-94. https://doi.org/10.17163/uni.n36.2022.03

Salaverría, R., Buslón, N., López-Pan, F., León, B., López-Goñi I., & Erviti, M. C. (2020). Desinformación en tiempos de pandemia: tipología de los bulos sobre la Covid-19. Profesional de la información, 29(3), e290315. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.may.15

Santos, G. F. (2020). Social media, disinformation, and regulation of the electoral process: a study based on 2018 Brazilian election experience. Revista de Investigações Constitucionais, 7(2), 429-449, https://doi.org/10.5380/rinc.v7i2.71057

Silveira, P., & Gancho, C. (2021). University students engagement with fake news: the portuguese case. Observatorio (OBS*), 15(1), 23-37. https://doi.org/10.15847/obsOBS15120211696

Sobral, F., & Nina de Morais, N. S. (2020). Información falsa en la red: la perspectiva de un grupo de estudiantes universitarios de comunicación en Portugal. Revista Prisma Social, 29, 172-194. https://revistaprismasocial.es/article/view/3593

Syrovátka, J., Hořejš, N., & Komasová, S. (2023). Towards a model that measures the impact of disinformation on elections. European View, 22(1), 119-130. https://doi.org/10.1177/17816858231162677

Tandoc, E. C., Lim, Z. W., & Ling, R. (2018). Defining “Fake News”: A typology of scholarly definitions. Digital Journalism, 6(2), 137-153. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1360143

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS, FUNDING AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors' contributions:

Conceptualization: Poch-Butler, Santana Lois and Gelado-Marcos, Roberto. Software: De la Calle Velasco, Guillermo and Ventura-Salom, Borja. Validation: Poch-Butler, Santana Lois; Gelado-Marcos, Roberto and Ventura-Salom, Borja. Formal analysis: Poch-Butler, Santana Lois; Gelado-Marcos, Roberto and Ventura-Salom, Borja. Data curation: Poch-Butler, Santana Lois; Gelado-Marcos, Roberto; Ventura-Salom, Borja and De la Calle Velasco, Guillermo. Drafting-Preparation of the original draft: Poch-Butler, Santana Lois; Gelado-Marcos, Roberto and Ventura-Salom, Borja. Drafting-Revision and Editing: Poch-Butler, Santana Lois; Gelado-Marcos, Roberto and Ventura-Salom, Borja. Visualización: Ventura-Salom, Borja. Supervision: Poch-Butler, Santana Lois; Gelado-Marcos, Roberto; Ventura-Salom, Borja and De la Calle Velasco, Guillermo. Project management: Poch-Butler, Santana Lois; Gelado-Marcos, Roberto; Ventura-Salom, Borja and De la Calle Velasco, Guillermo. All authors have read and accepted the published version of the manuscript: Apellido Poch-Butler, Santana Lois; Gelado-Marcos, Roberto; Ventura-Salom, Borja and De la Calle Velasco, Guillermo.

Funding: This research is part of the IBERIFIER project, funded by the European Union through the CEF-TC-2020-2 agreement, with reference 2020-EU-IA-0252 and it has also received funding from the Vice-Rectorate for Research, Transfer and Scientific Dissemination of the CEU San Pablo University.

Acknowledgements: To the fact-checkers participating in the interviews and to the IBERIFIER verification agencies for making available such a comprehensive and systematic database.

AUTHORS:

Poch-Butler, Santana Lois

Rey Juan Carlos University.

Master in Applied Communication Research and predoctoral researcher hired in the Department of Audiovisual Communication and Advertising at the Rey Juan Carlos University,teaching the subjects of Communication Research Methods, Audience Research, Communication and Crisis Management, Communication and Public Opinion and Principles of Communication. The author is also a member of the Comunicancer research group. the research interests of the author are strategic communication, crisis communication and news disruption.

Índice H: 1

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2590-7795

Scopus ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=57224449188

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?hl=es&user=E7PvxdkAAAAJ

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Santana-Poch

Academia.edu: https://independent.academia.edu/SantanaLois

Roberto Gelado-Marcos

CEU San Pablo University.

Professor of Journalism and Digital Narratives at the University CEU San Pablo, with two 6-year research fellowships from ANECA CNEAI. MA Global Media from the University of East London and PhD in Communication and Knowledge Management from the Universidad Pontificia de Salamanca. He is the MR of the USPCEU node of the IBERIFIER hub, and previously also led the research project “Study of the conditioning factors of disinformation and proposed solutions against its impact depending on the degrees of vulnerability of the groups analyzed”, funded by Facebook and the Luca de Tena Foundation.

Índice H: 8

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4387-5347

Scopus ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=57205270814

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=LJZ837EAAAAJ&hl=en

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Roberto-Gelado

Academia.edu: https://uspceu-es.academia.edu/RobertoGelado

Borja Ventura-Salom

CEU San Pablo University.

PhD in Journalism from the UC3M, Master in Media Research from the URJC. Associate Professor of the Department of Journalism and Digital Narratives and the Master of Data Analysis and Dissemination of the USP-CEU. Member of the GIR ICOIDI, of the USPCEU, collaborator of the GCID Nodes, from the URJC. Member of the technical editorial board of the journal index.comunicación (Scopus Q1). He was responsible for Communication of the Secretary of State for Digitalization and AI of the Government of Spain.

Índice H: 3

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5152-1357

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=8bV9aosAAAAJ

Scopus: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=58179012900

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Borja-Ventura-Salom

Academia: https://uspceu-es.academia.edu/BorjaVentura

Guillermo de la Calle Velasco

CEU San Pablo University.

Professor and researcher. He holds a doctorate in Computer Science (Artificial Intelligence) and a doctorate in Computer Science Engineering from the Polytechnic University of Madrid (UPM), with 2 six-year research fellowships from ANECA CNEAI. He belonged to the Biomedical Informatics Group (UPM), and he was hired to work in different national and international (European) research projects. He is author of more than 25 scientific articles. He is currently a member of the Biomedical Engineering research group BIOLAB at CEU San Pablo University.

Índice H: 10

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8147-3576

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=aE1kV_EAAAAJ&hl=es

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Guillermo-De-La-Calle-Velasco

Scopus: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=23495177000

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Guillermo-De-La-Calle-Velasco