Revista Latina de Comunicación Social. ISSN 1138-5820

Correlation between media consumption associated with fake news and mindset: a study from a media ecology perspective

Felipe Anderson Rios Incio

César Vallejo University. Peru.

![]()

Ángel Emiro Paéz Moreno

Boyacá University. Colombia.

![]()

Milagros Thalía Leiva Marín

César Vallejo University. Peru.

Francisco Javier Barquero Cornelio

César Vallejo University. Peru.

Luis Ernesto Paz Enrique

National Autonomous University of Mexico. Mexico.

luisernestopazenrique@gmail.com

![]()

This article is the result of the research project approved by the César Vallejo University Research Fund 2023. RESOLUTION OF THE VICE-RECTORATE FOR RESEARCH N°173-2023-VI-UCV (for its acronym in Spanish).

How to cite this article / Standard reference:

Ríos Incio, Felipe Anderson; Páez Moreno, Ángel Emiro; Leiva Marín, Milagros Thalía; Barquero Cornelio, Francisco Javier y Paz Enrique, Luis Ernesto (2025). Correlation between media consumption associated with fake news and mindset: a study from a media ecology perspective. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 83, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.4185/RLCS-2025-2391

Date Received: 07/23/2024

Acceptance Date: 11/26/2024

Date of Publication: 03/31/2025

![]()

ABSTRACT

Introduction: This study explored the relationship between media consumption associated with fake news and the mindset of citizens in Peru from the perspective of media ecology. Methodology: The research is quantitative and correlational. A sample of 937 citizens, aged 19 to 59 years, from the 25 departments of the country were surveyed. Data were analyzed using SPSS and Pearson's correlation coefficient. Results: A positive correlation was found between consumption associated with fake news and mindset. This relationship suggests that the characteristics of fake news (surrealism, exaggeration, impact, emotionality, persuasiveness) are associated with people who consider their intelligence as malleable. The results also indicate a generalized distrust of social networks and their association with fake news. Discussion: The relationship between fake news consumption and mindset points to the need to generate spaces for the responsible social use of ICTs and counteract disinformation. Peruvians interviewed are aware of the dangers lurking in the media ecosystem. Conclusions: Peruvians, according to the results of the study, live as if they were fish in water in the media ecosystem, being aware of the dangers lurking due to disinformation and fake news.

Keywords: media ecology; hoaxes; Media consumption; fake news; mindset.

1. INTRODUCTION

In a world flooded with digital information, the phenomenon of the viral spread of hoaxes or fake news has become a growing concern. From heated election debates to widespread confusion during the COVID-19 pandemic, the spread of misinformation has shaken the foundations of Latin American society. According to Diazgranados (2020), a shocking 79% of Peruvians, and more than half of Latin Americans in general, have difficulty distinguishing between fake and real news. Despite ongoing efforts to combat fake news, the challenge persists and it is clear that a multidisciplinary solution is needed (Blázquez-Ochando, 2019).

In this context, concepts such as fake news and post-truth play a crucial role in understanding the dynamics of disinformation. Fake news is defined as false information intentionally designed to deceive and shape public opinion, exploiting characteristics such as emotional impact and persuasiveness (Blazquez-Ochando, 2018). Post-truth, in turn, is characterized by prioritizing emotions and personal beliefs over objective facts, creating an environment conducive to the spread of hoaxes (Avaro, 2021). From a media ecology perspective, these elements interact in an ultra-mediated environment where digital devices and platforms not only connect users, but actively shape their perceptions and behavior (López-Paredes & Carrillo-Andrade, 2024).

1.1. A view from the media ecology

Faced with the problem of disinformation, an approach focused on the ecology of the media has been adopted. This complex and systemic field of study is not only interested in the educational and developmental potential of digital platforms, but also evaluates their role as channels for the dissemination of false information or hoaxes. Within this framework, the concept of ultra-mediation expands the understanding of how devices and digital platforms not only connect users, but also actively shape their perceptions and behaviors in highly interactive networks (López-Paredes & Carrillo-Andrade, 2024). The ultra-mediated society is characterized by the intertwining of these connections in reticular structures that reinforce the flow of disinformation, such as fake news, through echo chambers and filter bubbles (Rodríguez, 2017, cited in López-Paredes & Carrillo-Andrade, 2024). Media ecology focuses on understanding how different media influence human perception and cognition. According to Islas (2015), this approach goes beyond the conventional view and is considered a meta-analytical discipline that examines how technologies and media have triggered significant changes in societies throughout history.

At its core, media ecology is a holistic and dynamic analysis of the interaction between technology, media content, and audiences. This approach recognizes that media are not simply transmitters of information, but that they shape the environment in which people develop. To this perspective is added the theory of ultra-mediation, which proposes that digital networks not only transmit information, but also structure the flow of meanings, reconfiguring human perception and cognition (López-Paredes & Carrillo-Andrade, 2024). This approach is key to understanding how fake news is disseminated in an ultra-mediated society, where users act as interconnected nodes in interactive and reticular networks (Goyal, 2007).

Likewise, Scolari (2012) argues that it is essential to analyze the hybridization of media in order to understand the emergence of new channels that combine different devices, languages, and functions. Similarly, McLuhan (1977) argued that the medium itself is an environment, a place in which people thrive and which nurtures the technologies that shape our cognitive and perceptual systems. According to McLuhan (1977), media ecology involves organizing different media so that they support each other rather than canceling each other out. For example, radio may contribute more to literacy than television, but the latter may be a valuable tool for language learning. In this study, one of the first steps is to identify the media that Peruvians use and trust the most, as well as to determine how the choice of a particular medium can influence the mentality or "mindset" when receiving hoaxes.

From the perspective of Colombo (2022), the growing trend of ecological awareness, driven by geopolitical factors and the Covid-19 pandemic, raises theoretical questions in the self-management of communication. The author proposes a question about how to define good communication, its importance and the need to avoid conflicts in online discussions. This vision is based on the premise that our unique way of communicating is what defines us as a human species.

Thus, the study of media ecology provides a crucial approach to understanding disinformation and its impact on human cognition. Media hybridization and its effect on the dissemination of fake news has become an essential phenomenon to analyze. In light of the above, the following research question was posed What is the relationship between media consumption associated with fake news and the mindset of Peruvian citizens between the ages of 19 and 59 from the perspective of media ecology? As a research hypothesis, it was proposed that there is a relationship between both variables.

1.2. Media consumptionandhoaxes

In studies such as Tóth et al. (2023), Näsi et al. (2021), Rapada et al. (2021), Levy (2021), Barrios-Rubio (2022), Hwang et al. (2021), Pérez-Escoda et al. (2021), Talabi et al. (2022), Kim et al. (2021), Tejedor et al. (2021), and Baptista and Gradim (2020), different explanations have been found about media consumption and hoaxes, based on phenomena such as political preferences, educational level, and the use of social media on mobile devices.

Firstly, a link is recognized between the news sources people choose and their political and ideological leanings, as suggested by the research of Tóth et al. (2022). This study suggests that exposure to news sources that challenge our attitudes can reinforce these attitudes and increase polarization. Näsi et al. (2021) address the fear of public violence and find a correlation with the use of different media. As the consumption of social media and information intensifies, concern about street violence seems to increase, especially among those persons with secondary or higher education.

Several studies emphasize the role of social media. Rapada et al. (2021) suggest that social media can influence consumer behavior when information comes from verified sources. Levy (2021) delves deeper into this issue, showing how social media algorithms can limit exposure to contradictory news and potentially increase polarization. Barrios-Rubio (2022) discusses a mediamorphosis of analog media that integrates them into a 360-consumer culture, while Hwang et al. (2021) find a positive correlation between the adoption of social networks on smartphones and consumer gratification.

Pérez-Escoda et al. (2021) examine Generation Z and their relationship with the media, social media, and fake news. Although they recognize social media as a source prone to misinformation, they are still the main source of news consumption for this generation. Talabi et al. (2022) contribute to this conversation with a study on the impact of fake news on the perception of the COVID-19 vaccine. Tejedor et al. (2021) and Trnini’c et al. (2022) add to the debate by examining the perception of fake news among students and different generations, respectively. Both studies show a strong link between fake news and politics.

Finally, research by Baptista and Gradim (2020) suggests that certain demographic groups, including conservatives, the elderly, and the less educated, are more likely to believe and disseminate fake news. However, Kim et al. (2021) offer a hopeful vision, suggesting solutions such as digital media literacy and the creation of computational models to combat disinformation. This analysis of different studies reveals a complex and nuanced picture of media consumption and hoaxes. Each study contributes a piece of the puzzle, illustrating how digital and social media have changed the way people consume information and are sometimes swept up in misinformation. While certain demographic groups may be more likely to believe and disseminate fake news, digital media literacy, along with innovative technologies and strategies, offers a glimmer of hope to combat this problem.

1.3. Mindset

Recent research in the social sciences has explored how factors such as intelligence, education, and thinking style can influence the way individuals interpret and respond to media messages. Rather than focusing on individual characteristics, however, the studies cited focus on how thinking styles can be used to educate and empower diverse populations. Through the findings of Balthip et al. (2022), Bailey et al. (2022), Brandisauskiene et al. (2021), Haukås and Mercer (2021), Meierdirk and Fleischer (2022), Sun et al. (2021), Martini et al. (2022), and Huang and Xie (2021), this phenomenon was explored.

Balthip et al. (2022) analyze how Thai adolescents cultivate a gratitude mindset, an aspect that is essential for promoting their health and well-being, stating that cultivating a gratitude mindset is associated with several factors, particularly culture and religion.

Bailey et al. (2022), meanwhile, highlight how educators adopted an adaptive mindset in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, shifting the narrative from fear to empowerment.

In addition, Brandisauskiene et al. (2021) highlight positive correlations between teacher support, growth mindset, and student achievement, while Haukås and Mercer (2021) highlight the role of teachers' beliefs in their readiness for professional development. Both authors address the importance of growth mindset in education. Meierdirk and Fleischer (2022) examine the relationship between growth mindset, resilience, and student teacher performance and find that student teachers who received a "satisfactory" grade were more likely to have a resilience mindset than those who received a "good" grade. On the other hand, Sun et al. (2021) focus on cultural differences in mindsets and their influence on perception of intelligence and academic performance, demonstrating the existence of systematic cross-cultural differences in intelligence mindset that are not associated with motivation or academic success in the same way across cultures.

Martini et al. (2022) examine how the conspiracy mentality can lead to misinformation and overestimation of certain issues, such as immigration. Finally, Huang and Xie (2021) explore the sociodemographic correlates of mindset in China, highlighting its relationship with education, occupation, life events, and general well-being. The studies reviewed underscore the importance and influence of mindset in various areas of life, from education to the perception and processing of information. In the age of misinformation, understanding and shaping mindset can be a valuable tool for promoting resilience, growth, and well-being.

This understanding extends beyond the individual to the social and political spheres. The ability to distinguish true from false information and to resist manipulative influences is becoming fundamental in an increasingly interconnected and digitized society. These findings open new avenues for implementing educational programs and awareness campaigns that emphasize the importance of developing a critical and reflective mindset, especially in environments where information can be easily distorted or misinterpreted. Promoting these skills not only benefits individuals in their daily lives, but also contributes to strengthening the democratic structure and social fabric by fostering more informed, critical and responsible citizens.

2. OBJECTIVES

As a general objective, the aim is to determine the relationship between media consumption associated with fake news and the mindset of citizens aged 19 to 59 in Peru from the perspective of media ecology. The specific objectives are to measure the frequency of use and trust in the media, to identify the media associated with fake news, to measure the degree of relationship between media consumption and the dimensions of the mindset and to measure the degree of relationship between association of fake news and the dimensions of the mindset.

3. METHODOLOGY

The research has a quantitative approach, with a non-experimental design and a correlational scope. To collect information, a questionnaire validated (content, construct and criterion) by Burgoyne and Macnamara (2021) and Pérez-Escoda et al. (2021) was used as an instrument. Also, the instrument obtained by applying a pilot test a Cronbach's Alpha coefficient of α:.98, which indicates that the instrument is reliable for application in Peruvian citizens.

The population consisted of 15,742,782 citizens between the ages of 19 and 59 from the 25 departments of Peru, where 51% of the participants were women and 49% were men (National Institute of Statistics and Informatics [INEI, for its acronym in Spanish], 2017). To calculate the probabilistic and representative sample size to the population, the formula for populations with a finite universe was used. Considering a margin of error e:3.2, confidence level z:95%, a sample of 937 citizens was obtained. Of these, 456 were men and 482 were women, stratified by departments to ensure equal representation of all departments of the country.

The instrument that measures the media consumption variable associated with fake news is disaggregated into two dimensions: media consumption and fake news association. Also, the mindset variable is measured with two dimensions: mindset assessment profile and measure of mindset. The participants in the research answered 4 items for demographics, 33 items for media consumption associated with fake news and 16 items for mindset.

The instrument was designed using a questionnaire on Google Forms and collected the consent of each citizen before freely conducting the survey from May 1st and June 23, 2023. The statistical package SPSS version 26 was used for data processing and analysis. Likert scale was used as the measurement scale. The values of 1. Never, 2. Little, 3. Occasionally, 4. Often, 5. Always. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to verify the normality of the data in both variables. The p-values exceeded the significance threshold of 0.05, which would indicate a normal distribution. However, given the large sample size of 937 participants, it is important to recognize that the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test may be sensitive to small deviations from normality that are practically irrelevant. Finally, Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to test the research hypotheses (Hernández Lalinde, 2018).

4. RESULTS

4.1. Descriptiveresults

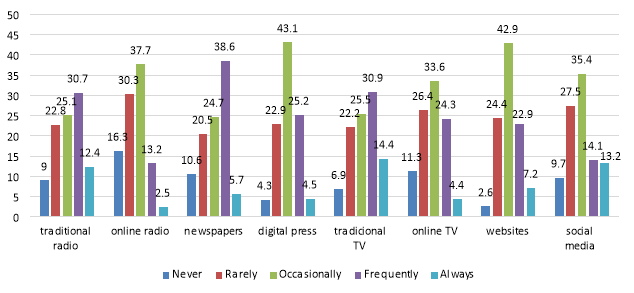

Figure 1. Frequency of media use.

Source: Own elaboration.

In Figure 1, we can see that 77.1% always or often use social media when consuming information, compared to 80% who say they use traditional radio (never, rarely or occasionally).

Figure 2. Trust in the media.

Source: Own elaboration.

As shown in Figure 2, 72.6% and 70.3% trust social media and the digital press to a lesser extent (never, rarely or occasionally). In contrast, 43.1% trust radio (always or often) and 45.3% trust traditional television.

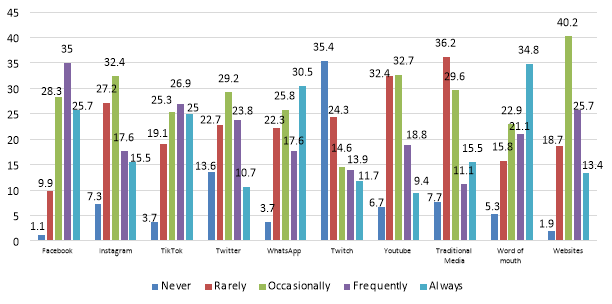

Figure 3. Frequency of network use.

Source: Own elaboration.

In Figure 3, WhatsApp is presented with 82.9% of citizens always or often using it. This is followed by Facebook Instagram (62.8%), YouTube (65.6%) and TikTok (36.6%), which are always or often used.

Figure 4. Fake News related media.

Source: Own elaboration.

In Figure 4, 62.75% of citizens associate fake news with Facebook. 55.9% associate it with word of mouth, 51.9% with TikTok and 48.1% with WhatsApp (always or often). On the other hand, 73.5% associate it to a lesser extent (never, rarely or occasionally) with traditional media.

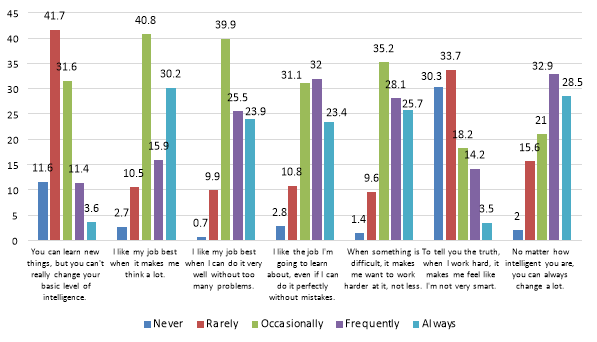

Figure 5. Mindset assessment profile.

Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 5, which evaluates the mindset assessment profile, shows a tendency among respondents to believe that intelligence can be modified (84.9%), and it can be noted a preference for work that involves thinking (54%) and learning (55.4%). 60.1% feel motivated in the face of difficulties and 82.2% do not feel less intelligent when working hard.

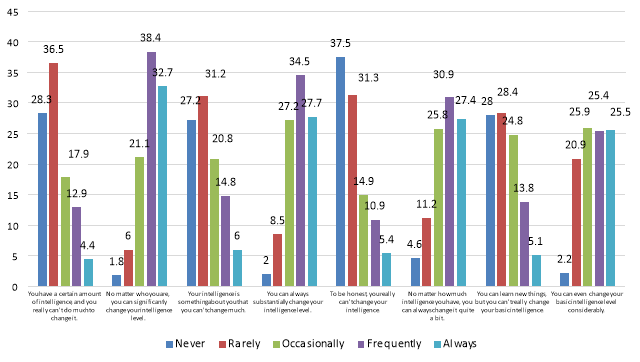

Figure 6. Measure of mindset.

Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 6 shows that the majority do not consider intelligence as fixed (82.7%) and believe that it can be significantly changed (71.1%). There was a split in the belief that the basic level of intelligence can be significantly changed, with 49% disagreeing and 50.9% agreeing.

4.2. Inferential results

Figure 7. Correlation between media consumption related to fake news and mindset

Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 7 shows a Pearson's r statistic value of 0.493, as well as a highly significant correlation between the variable media consumption related to fake news and mindset in 937 citizens from all departments of Peru. Therefore, it can be affirmed with 99% confidence that there is a moderate degree of positive correlation between both variables, since the sig. value (bilateral) is less than the required <.001.

Table 1. Correlation between media consumption and mindset assessment profile

|

|

Media consumption |

Mindset Assessment Profile |

||

|

Media consumption |

Pearson’s correlation |

1 |

,512** |

|

|

Sig. (bilateral) |

|

<.001 |

||

|

N |

937 |

937 |

||

|

Mindset Assessment Profile |

Pearson’s correlation |

,512** |

1 |

|

|

Sig. (bilateral) |

<.001 |

|

||

|

N |

937 |

937 |

||

|

**. The correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (bilateral). |

||||

Source: Own elaboration.

Table 1 shows a Pearson's r statistic value of 0.512, as well as a highly significant correlation between the dimensions of media consumption and mindset assessment profile in 937 citizens from all departments of Peru. Therefore, it can be affirmed with 99% confidence that there is a moderate degree of positive correlation between both dimensions, since the sig. value (bilateral) is less than the required <.001.

Table 2. Correlation between media consumption and measure of mindset

|

|

Media consumption |

Measure of mindset |

|

|

Media consumption |

Pearson’s correlation |

1 |

,269** |

|

Sig. (bilateral) |

|

<.001 |

|

|

N |

937 |

937 |

|

|

Measure of mindset |

Pearson’s correlation |

,269** |

1 |

|

Sig. (bilateral) |

<.001 |

|

|

|

N |

937 |

937 |

|

|

**. The correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (bilateral). |

|||

Source: Own elaboration.

Table 2 shows a Pearson's r statistic value of 0.269, as well as a highly significant correlation between the dimensions of media consumption and measure of mindset in 937 citizens from all departments of Peru. Therefore, it can be affirmed with 99% confidence that there is a low degree of positive correlation between both variables, since the sig. value (bilateral) is less than the required <.001.

Table 3. Correlation between media consumption and mindset assessment profile.

|

|

Fake news association |

Mindset Assessment Profile |

|

|

Fake news association |

Pearson’s correlation |

1 |

,392** |

|

Sig. (bilateral) |

|

<.001 |

|

|

N |

937 |

937 |

|

|

Mindset Assessment Profile |

Pearson’s correlation |

,392** |

1 |

|

Sig. (bilateral) |

<.001 |

|

|

|

N |

937 |

937 |

|

|

**. The correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (bilateral). |

|||

Source: Own elaboration.

In Table 3, a statistical value of Pearson's r of 0.392 can be seen, in addition to a very significant correlation between the association dimensions of fake news and the mindset assessment profile in 937 citizens from all departments of Peru. Therefore, it can be stated with 99% confidence that there is a degree of low positive correlation between both dimensions, given that the sig. value (bilateral) is less than the required <.001.

Table 4. Correlation between media consumption and measure of mindset.

|

|

Fake News Association |

Measure of mindset |

|

|

Fake news |

Pearson’s correlation |

1 |

,208** |

|

Sig. (bilateral) |

|

<.001 |

|

|

N |

937 |

937 |

|

|

Measure of mindset |

Pearson’s correlation |

,208** |

1 |

|

Sig. (bilateral) |

<.001 |

|

|

|

N |

937 |

937 |

|

|

**. The correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (bilateral). |

|||

Source: Own elaboration.

In Table 4, a statistical value of Pearson's r of 0.208 can be seen, in addition to a very significant correlation between the dimensions fake news association and measure of mindset in 937 citizens of all departments in Peru. Therefore, it can be stated with 99% confidence that there is a degree of low positive correlation between both dimensions, given that the sig. value. (bilateral) is less than the required <.001.

5. DISCUSSIO AND CONCLUSIONS

The results of the research show that the relationships found vary significantly by age group. For example, the correlation between fake news consumption and critical mindset is more pronounced among young adults (19 to 35 years old), while the correlation weakens among those over 50. This finding, based on the applied regression projection, suggests that generational factors play a key role in the interpretation and consumption of media, which is consistent with previous research on cognitive differences in information processing (Pérez-Escoda et al., 2021). Similarly, the projection suggests that, under similar scenarios, the influence of fake news could be intensified in younger populations, given their greater exposure to and trust in social media as a primary source of information.

Furthermore, these findings suggest that individuals' predisposition to believe or dismiss information may be influenced more by their general mindset towards media and information than by their political beliefs or educational level. This finding underscores the need to address the mindset of media consumers as a critical factor in media literacy strategies and efforts to combat disinformation. The research also highlights the importance of developing programs that promote critical thinking and analytical attitudes toward the media, not only in educational settings but also among the general population. These programs should be designed with the specific cultural and social characteristics of the Peruvian population in mind to ensure their effectiveness and relevance. In conclusion, this study provides valuable insights into how individual mindsets affect the perception and consumption of news, which can guide future educational policies and practices in Peru and similar contexts.

On the one hand, it is observed that there is a congruence between the research results and some previous findings in the scientific literature. Such is the case of the popularity of social networks as a means of information, something that had already been identified by Pérez-Escoda et al. (2021) and Hwang et al. This latest study also highlights the positive relationship between the use of social media on smartphones and consumer satisfaction, which is consistent with the finding in this study that the majority of respondents prefer social networks as a means of communication.

Inspired by the vision of Islas-Carmona and Arribas Urrutia (2023) on McLuhan's work, this study recognizes the importance of understanding how media, beyond being mere transmission channels, act as environments that shape the perception and behavior of individuals. In this sense, the concept of ultra-mediation, as proposed by López-Paredes and Carrillo-Andrade (2024), allows to extend this vision by integrating the way in which digital networks not only connect users, but also reconfigure their perception of the environment and their social interactions. These reticular connections, typical of an ultra-mediated society, create behavioral patterns that directly influence the way people interpret and respond to fake news. This concept is essential for understanding the relationship between consumers' mindset and their responses to fake news, where the media not only report, but also actively shape cognition and attitudes.

However, not all observations are consistent with previous studies. When it comes to trusted sources for news consumers, our results differ slightly from what other researchers have proposed. Although some studies, such as Baptista and Gradim (2020), suggest that certain demographic groups, including the less educated, are more likely to believe and spread fake news, our data do not support this hypothesis. On the contrary, we find that while a significant number of respondents use and trust social networks, they do not necessarily consider them to be reliable sources of information.

On the other hand, to avoid falling into discriminatory judgments that associate levels of intelligence or education with susceptibility to the consumption and dissemination of hoaxes, the research focused on decoupling the notions of intelligence and education from the consumption and dissemination of fake news, opting instead to investigate the influence of the mentality or "mindset" of individuals. From the perspective of ultra-mediation, social media, by acting as echo chambers and filter bubbles, reinforce the selective exposure of information in line with existing prejudices (Rodríguez, 2017, cited in López-Paredes & Carrillo-Andrade, 2024). This phenomenon, combined with the strategically crafted characteristics of fake news, increases the susceptibility of individuals whose mindset is more reactive or susceptible to change. Using the Mindset Assessment, a validated diagnostic tool, it was shown that people's mindsets can indeed be susceptible to change. This finding is consistent with recent research suggesting that mindset may be a critical psychological factor that is strongly associated with multiple outcomes, including an individual's level of education, cognitive abilities, attitudes, and well-being (Huang & Xie, 2021).

The research is also consistent with the narrative established by recent scientific literature, which places considerable emphasis on the role of mindset in interpreting and responding to media messages. Like Balthip et al. (2022), Bailey et al. (2022), Brandisauskiene et al. (2021), Haukås and Mercer (2021), Meierdirk and Fleischer (2022), Sun et al. (2021), Martini et al. (2022), and Huang and Xie (2021), this research acknowledges and extends the influence of mindset on information consumption and interpretation.

However, this article takes an additional step by examining the correlation between mindset and susceptibility to fake news. This finding is an update to existing research and may open new avenues for studying the role of mindset in the dissemination of disinformation. The positive correlations found between media consumption associated with fake news and mindset may indicate how the success of fake news may be related to its strategically crafted features to capture the attention of those with mindsets more susceptible to change.

Ultimately, it reaffirms the importance of mindset in how individuals interpret and respond to information. It also adds a new layer of complexity by introducing the idea that mindset may play a crutial role in susceptibility to fake news. This approach resonates with the principles of media ecology as described by Islas-Carmona and Arribas Urrutia (2023), where the interaction between media and the mindset of individuals becomes a crucial field of study. Understanding this dynamic is fundamental to developing effective communication and media education strategies aimed at improving individuals' ability to recognize and question the information they consume. As such, the research serves as both an endorsement of the existing literature and an extension and update of it. In an era rife with misinformation, understanding and shaping mindsets can be a valuable tool in fostering resilience, growth, and ultimately the veracity of the information consumed.

Therefore, the findings of this study are in line with the approach of media ecology, which recognizes the essential role of different media in the formation of perception and cognition (Islas, 2015). In line with this approach, it is argued that each medium represents a unique environment that can shape the understanding of the world. This research supports this perspective by demonstrating the correlation between the consumption of certain types of media, especially those related to the dissemination of fake news, and the mentality of individuals within the Peruvian population between the ages of 19 and 59.

Similarly, within the concept of media hybridization proposed by Scolari (2012), a diversity of channels is observed, each with different devices, languages and functions. This article agrees with that notion, highlighting the influence that the choice of certain media can have on the recipient's mindset. This finding shows that the choice of media can have a significant impact on the way people interpret and respond to information, which is an essential component for understanding the spread of hoaxes.

The theory of media ecology, as analyzed in the work of Islas Carmona and Arribas Urrutia (2023), emphasizes the importance of considering how digital media create "environments" that affect not only what we see and how we see it, but also how we think and how we respond to our environment. This approach is crucial to understanding how the consumption of fake news can influence people's mindset, leading them to interpret information differently based on their exposure to certain types of media.

In line with McLuhan's (1977) argument that the environment shapes the technologies that shape our cognitive and perceptual systems, this study provides evidence of the strong correlation between an individual's mindset and their consumption of specific media. Of particular importance is the discovery of how this correlation can affect an individual's susceptibility to fake news, thereby expanding our understanding of how the media can influence our perception and cognition.

This understanding is consistent with McLuhan's vision, highlighted by Islas-Carmona and Arribas Urrutia (2023), of the powerful influence of the media on the configuration of our experiences and perceptions. The media's ability to shape our understanding of the world and our receptivity to different types of information becomes a central axis in the study of fake news. This approach allows us to look beyond the content of fake news and consider how the inherent characteristics of digital media may contribute to an increased susceptibility to disinformation.

Finally, also aligned with McLuhan's (1977) vision of organizing media to support rather than cancel each other out, this article suggests that a deeper understanding of mindset can be a valuable addition to media ecology. In addition, considering the theory of ultra-mediation, it can be observed that digital media not only shape the contents we consume, but also the ways we interpret these contents, creating patterns of perception and response that are unique to an ultra-mediated society (López-Paredes & Carrillo-Andrade, 2024). This reinforces the idea that addressing the problem of fake news requires both effective media literacy and a deep understanding of the interactions between media and mindset. By focusing not only on media and its effects, but also on how individuals' mindset can influence their interpretation and response to information, this study provides a more complete and nuanced view of how misinformation spreads. This mindset-centered approach can be a valuable complement to media ecology in the quest to understand and address the problem of the spread of hoaxes.

6. REFERENCES

Avaro, D. (2021). La posverdad. Una guía introductoria. Andamios, 18(46), 117-142. https://doi.org/10.29092/uacm.v18i46.840

Bailey, F., Kavani, A, Johnson, J. D., Eppard, J., & Johnson, H. (2022). Changing the narrative on COVID-19: Shifting mindsets and teaching practices in higher education. Policy Futures in Education, 20(4) 492-508. https://doi.org/10.1177/14782103211055189

Balthip, K., Suwanphahu, B., & McSherry, W. (2022). Achieving Fulfilment in Life: Cultivating the Mindset of Gratitude Among Thai Adolescents. SAGE Open, 12(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211070791

Baptista, J. P., & Gradim, A. (2020). Understanding Fake News Consumption: A Review. Social Sciences, 9(10), 185-195. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9100185

Barrios-Rubio, A. (2022). The Colombian Media Industry on the Digital Social Consumption Agenda in Times of COVID-19. Information, 13(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.3390/info13010011

Blázquez-Ochando, M. (2019). El problema de las noticias falsas: detección y contramedidas. En G. A. Torres Vargas, & M. T. Fernández Bajón (Coords.), Verdad y falsedad de la información (pp. 13-43). UNAM, Instituto de Investigaciones Bibliotecológicas y de la Información.

Brandisauskiene, A., Buksnyte-Marmiene, L., Cesnaviciene, J., Daugirdiene, A., Kemeryte-Ivanauskiene, E., & Nedzinskaite-Maciuniene, R. (2021). Connection between Teacher Support and Student's Achievement: Could Growth Mindset Be the Moderator? Sustainability, 13(24), 136-142. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413632

Burgoyne, A. P., & Macnamara, B. (2021). Reconsidering the Use of the Mindset Assessment Profile in Educational Contexts. Journal of Intelligence, 9(3), 39-49. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence9030039

Colombo, F. (2022). A media ecology for a platform society. En D. E. Viganò, S. Zamagni & M. Sánchez Sorondo (Eds.), Changing Media in a Changing World (pp. 162-182). The Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences. http://tinyurl.com/ycybnzda

Diazgranados, H. (4 de febrero de 2020). 70% de los latinoamericanos desconoce cómo detectar una fake news. Kaspersky Daily. http://tinyurl.com/36upnp7n

Goyal, S. (2007). Connections: An Introduction to the Economics of Networks. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400829163

Haukås, Å., & Mercer, S. (2021). Exploring pre-service language teachers' mindsets using a sorting activity. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 16(3), 221-233. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2021.1923721

Hernández Lalinde, J. D., Espinosa Castro, F., Rodríguez, J. E., Chacón Rangel, J. G., Toloza Sierra, C. A., Arenas Torrado, M. K., Carrillo Sierra, S. M., & Bermúdez Pirela, V. J. (2018). Sobre el uso adecuado del coeficiente de correlación de Pearson: Definición, propiedades y suposiciones. Archivos Venezolanos de Farmacología y Terapéutica, 37(5), 587-595. http://tinyurl.com/yc6nh6nb

Huang, Q., & Xie, Y. (2021). Social-demographic correlates of mindset in China. Chinese Journal of Sociology, 7(4), 497-513. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057150X211041908

Hwang, J., Eves, A., & Stienmetz, J. L. (2021). The Impact of Social Media Use on Consumers' Restaurant Consumption Experiences: A Qualitative Study. Sustainability, 13(12), 65-81. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126581

Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (2017). Censos Nacionales XII de Población y VII de Vivienda, 22 de octubre del 2017, Perú: Resultados Definitivos. Lima, octubre de 2018. Recuperado de: https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/publicaciones_digitales/Est/Lib1544/

Islas, O. (2015). The media ecology: Complex and systemic meta-discipline. Palabra Clave, 18(4), 1057-1083. https://doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2015.18.4.5

Islas-Carmona, O., & Arribas Urrutia, A. (2023). Cuando el espejo retrovisor te lleva al futuro. Una revisión histórica sobre McLuhan y la Ecología de los Medios. Revista De Comunicación, 22(2), 261-270. https://doi.org/10.26441/RC22.2-2023-3240

Kim, B., Xiong, A., Lee D., & Han, K. (2021). A systematic review on fake news research through the lens of news creation and consumption: Research efforts, challenges, and future directions. PLoS ONE, 16(12), e0260080. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260080

Levy, R. (2021). Social Media, News Consumption, and Polarization: Evidence from a Field Experiment. American Economic Review, 111(3), 831-870. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20191777

López-Paredes, M., & Carrillo-Andrade, A. (2024). Cartografía de consumo de medios en Ecuador: de las mediaciones e hipermediaciones a una sociedad ultramediada. Palabra Clave, 27(1), e2712. https://doi.org/10.5294/pacla.2024.27.1.2

Martini, S., Guidi, M., Olmastroni, F., Basile, L., Borri, R., & Isernia, P. (2022). Paranoid styles and innumeracy: Implications of a conspiracy mindset on Europeans' misperceptions about immigrants. Italian Political Science Review/Rivista Italiana Di Scienza Politica, 52(1), 66-82. https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2021.26

Mcluhan, M. (1977). La comprensión de los medios como extensiones del hombre. Diana.

Meierdirk, C., & Fleischer, S. (2022). Exploring the mindset and resilience of student teachers. Teacher Development, 26(2), 263-278. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2022.2048687

Näsi, M., Tanskanen, M., Kivivuori, J., Haara, P., & Reunanen, E. (2021). Crime News Consumption and Fear of Violence: The Role of Traditional Media, Social Media, and Alternative Information Sources. Crime & Delinquency, 67(4), 574-600. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128720922539

Pérez-Escoda, A., Barón-Dulce, G., & Rubio-Romero, J. (2021). Mapeo del consumo de medios en los jóvenes: redes sociales, 'fakes news' y confianza en tiempos de pandemia. index.Comunicación, 11(2), 187-208. https://doi.org/10.33732/ixc/11/02Mapeod

Rapada, M. Z., Yu, D. E., Yu, K. D. (2021). Do Social Media Posts Influence Consumption Behavior towards Plastic Pollution? Sustainability, 13(22), 123-134. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212334

Scolari, C. A. (2012). Media Ecology: Exploring the Metaphor to Expand the Theory. Communication Theory, 22(2), 204-225. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2012.01404.x

Sun, X., Nancekivell, S., Gelman, S. A., & Shah, P. (2021). Growth mindset and academic outcomes: a comparison of US and Chinese students. npj Science of Learning, 6(21). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-021-00100-z

Talabi, F. O., Ugbor, I. P, Talabi, M. J., Ugwuoke, J. C., Oloyede, D., Aiyesimoju, A. B., & Ikechukwu-Ilomuanya, A. B. (2022). Effect of a social media-based counselling intervention in countering fake news on COVID-19 vaccine in Nigeria. Health Promotion International, 37(2). https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daab140

Tejedor, S., Portalés-Oliva, M., Carniel-Bugs, R., & Cervi, L. (2021). Journalism Students and Information Consumption in the Era of Fake News. Media and Communication, 9(1), 338-350. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v9i1.3516

Tóth, F., Mihelj, S., Štětka, V., & Kondor, K. (2023). A Media Repertoires Approach to Selective Exposure: News Consumption and Political Polarization in Eastern Europe. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 28(4), 884-908. https://doi.org/10.1177/19401612211072552

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS, FUNDING AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Authors' contributions:

Conceptualization: Rios Incio, Felipe Anderson. Software: Paéz Moreno, Ángel Emiro. Validation: Rios Incio, Felipe Anderson. Paéz Moreno, Ángel Emiro. Milagros Thalía, Leiva Marín. Barquero Cornelio, Francisco Javier. Paz Enrique. Formal analysis: Rios Incio, Felipe Anderson. Paéz Moreno, Ángel Emiro. Data curation: Rios Incio, Felipe Anderson. Paéz Moreno, Ángel Emiro. Paz Enrique, Luis Ernesto. Drafting -Preparation of the original draft: Rios Incio, Felipe Anderson. Paéz Moreno, Ángel Emiro. Milagros Thalía, Leiva Marín. Barquero Cornelio, Francisco Javier. Paz Enrique, Luis Ernesto. Drafting-Revision and Editing: Rios Incio, Felipe Anderson. Paéz Moreno, Ángel Emiro. All authors have read and accepted the published version of the manuscript: Rios Incio, Felipe Anderson. Paéz Moreno, Ángel Emiro. Milagros Thalía, Leiva Marín. Barquero Cornelio, Francisco Javier. Paz Enrique, Luis Ernesto. Funding: Esta investigación no tiene financiamiento externo.

Acknowledgments: The article is the result of the research project: SOCIODEMOGRAPHIC FACTORS AND THEIR RELATIONSHIP WITH MEDIA CONSUMPTION AND TRUST: A STUDY IN PERU. Approved by the Research Support Fund 2023 under the César Vallejo University. RESOLUTION OF THE VICE-RECTORATE FOR RESEARCH N°173-2023-VI-UCV (for its acronym in Spanish).

Conflict of interest: None.

AUTHORS:

Felipe Anderson Rios Incio

César Vallejo University.

Felipe holds a Ph.D. in Social Communication, a Master in Communication Sciences with specialization in Commercial Management and Marketing Communications. He also holds a Bachelor's Degree in Communication Sciences. He is lecturer in the Communication Sciences program at the Cesar Vallejo University, with initiative, responsibility and organization in his work. He works as a thesis advisor and jury. He is a research lecturer qualified by Concytec. He is the author of the book "Media Peru".

Índice H: 4

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7049-8869

Scopus ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=57539514800

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?hl=es&user=wCHiteIAAAAJ

Ángel Emiro Páez Moreno

Boyacá University.

Ángel is the author of the book "Electronic Government from the bottom up: A Proposal from Venezuela". He has more than 100 intellectual products in ICT and management. He is editor-in-chief of the peer-reviewed scientific journal InveCom, CEO of a digital branding agency and freelance social media manager. He is an advisor in communication, market research and e-government. He holds a Ph.D. in Social Sciences issued by the University of Zulia, a Master in Communication Sciences and a Bachelor in Social Communication. He is the founder of the Information Technology Chair in various Venezuelan Universities. He also a lecturer at both the University of Boyacá and the University of Zulia. He is a certified researcher in Colombia and President of the Association of Venezuelan Communication Researchers.

Índice H: 10

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0924-3506

Scopus ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=57188588484

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?hl=es&user=E_B1o30AAAAJ

César Vallejo University.

Milagro holds a Master in Public Relations and Corporate Image. I currently work as a lecturer in the main schools of Communication Science in the city of Trujillo.

Índice H: 2

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5977-5343

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?hl=es&user=swxyzRoAAAAJ

Francisco Javier Barquero Cornelio

César Vallejo University.

Francisco is a Social communicator, specializing in journalism, public relations and audiovisual production. He holds a Master in Public Relations and Corporate Image (UCV Trujillo). His work experience includes audiovisual producer at UCV Satelital Trujillo, producer and journalistic editor at Ad Media Producciones for América TV Trujillo, institutional image analyst at Servicio de Gestión Ambiental (SEGAT, for its acronym is Spanish), director of UCV Satelital Chiclayo, director of TV Cosmos in Chiclayo and Chepén. He is undergraduate lecturer at the César Vallejo University in Trujillo (Faculty of Communication Sciences), at the Private University of the North (Faculty of Communication Sciences and Faculty of Business), at the University of San Martín de Porres (Faculty of Communication Sciences, Tourism and Psychology) and at the University Señor de Sipán (Faculty of Humanities).

Índice H: 1

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6214-0381

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.es/citations?user=o8C0VZoAAAAJ&hl=es&oi=ao

Luis Ernesto Paz Enrique

National Autonomous University of Mexico.

Luis holds a bachelor's degree in Information Science. He is a professor in Teaching for Higher School Education (specialization in Philosophy). He also holds a Ph.D. in Sociological Sciences. He has taught undergraduate and postgraduate courses in several Latin American and Caribbean countries, mainly in Cuba, Mexico and Peru. He has published 147 scientific articles in refereed journals, 18 book chapters, 10 scientific books reviewed by academic peers. For his scientific activity, he received the Latin American Science Prize on Open Access (awarded by UNESCO, AmeliCA, Redalyc, CLACSO (for its acronym is Spanish) and the Autonomous University of Mexico State).

luisernestopazenrique@gmail.com

Índice H: 18

Orcid ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9214-3057

Scopus ID: https://www.scopus.com/authid/detail.uri?authorId=57188869997

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?hl=es&user=lx0fKg8AAAAJ